The Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo

October brought weeks of rain to the upper Isonzo valley,

turning to sleet on the heights. Italian observers on both sides of the valley

glimpsed the river through ragged gaps in the fog. One morning, they saw

Habsburg soldiers move steadily up the valley, two abreast on the narrow road,

towards the little town of Caporetto. No cause for alarm; they had to be

prisoners marching to the rear. Otherwise …

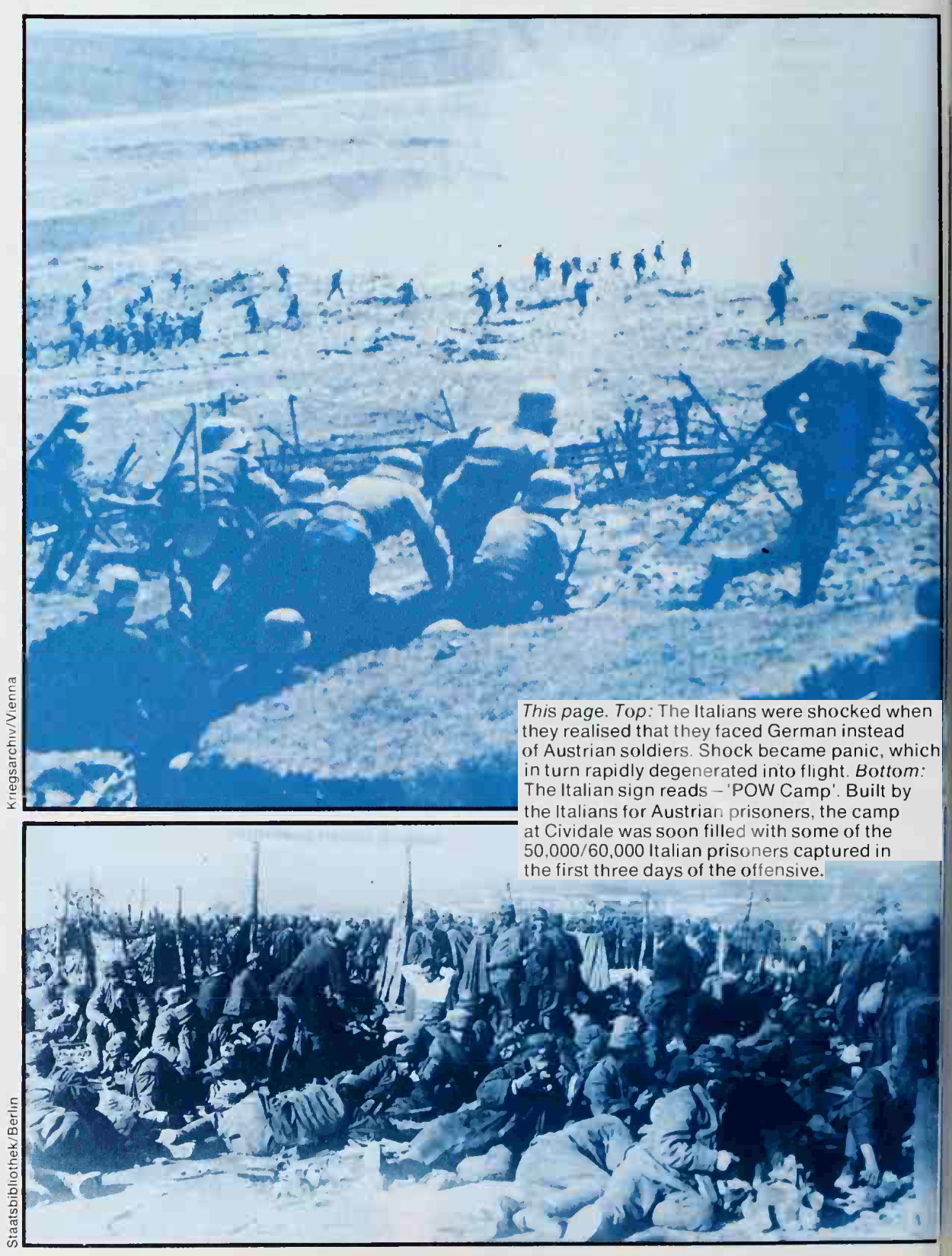

For the Italians, the Twelfth Battle began as something

unthinkable. By the time they realised what was happening, they were powerless

to stop it. Cadorna liked to say that he led the greatest army in Italy since

the Caesars. The last week of October 1917 turned this epic boast inside out;

no single defeat in battle had placed Italy in such peril since Hannibal

destroyed the Roman legions at Cannae, more than two thousand years before.

The unthinkable had a name: infiltration. On the other side

of Europe, while Capello’s Second Army died in droves behind Gorizia, the

German Eighth Army rewrote the tactical playbook. It happened on 1 September

1917, around the city of Riga, where the River Dvina flows into the Baltic Sea.

Aiming to paralyse the Russian lines rather than demolish them, the preliminary

bombardment was abrupt – no ranging shots – and deep, preventing the movement

of reserves. Protected by a creeping barrage, the assault troops crossed the

river upstream and took the Russians by surprise, punching through their lines

from several angles, attacking the weak points without trying to overwhelm all

positions at once. The Germans’ mobility and devolved command let them exploit

this method to the full.

Their success did not emerge from a vacuum. Since early

1916, if not before, the warring commanders had searched for tactical norms

that could, in Hew Strachan’s phrase, ‘re-establish the links between fire and

movement which trench warfare had sundered’. Falkenhayn’s initial bid for

breakthrough at Verdun sent stormtroopers ahead in groups after massive

bombardments that had destroyed French communications. The Russians discovered

other elements of infiltration with Brusilov’s brilliant offensive of May 1916.

The British tested different attack formations, turning infantry lines into

‘blobs’ or, later, diamonds. Although there was no magic key, infiltration

tactics emerged as a solution to attritional deadlock against defences that

were ‘crumbling or incomplete’. This was the situation in the Riga salient,

where the Russians were preparing to withdraw as the battle began, and the

garrison in the city escaped. And it was certainly the situation on Cadorna’s

upper Isonzo.

A week before the Riga operation, Emperor Karl wrote to the

Kaiser ‘in faithful friendship’. The Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo ‘has led me

to believe we should fare worse in a twelfth’. Austria wished to take the

offensive, and would be grateful if Germany could replace Austrian divisions in

the east and lend him artillery, ‘especially heavy batteries’. He did not ask

for direct German participation; indeed he excluded it, for fear of cooling the

Austrian troops’ rage against ‘the ancestral foe’. The Kaiser replied curtly

and referred the request to Ludendorff. The German general staff had already

assessed that the Austrians would be broken by the next Italian offensive,

which they expected before the end of the year. If Austria-Hungary collapsed,

as it probably would, Germany would be alone: an outcome that had to be

prevented. Meanwhile the Austrian high command – ignoring the Emperor’s scruple

– had separately suggested a combined offensive.

Ludendorff decided he could spare six to eight divisions

until the winter. He dusted off Conrad’s idea for an offensive across the upper

Isonzo between Tolmein and Flitsch. Hindenburg, the chief of the general staff,

sent one of his most able officers to reconnoitre the ground. An expert in

mountain warfare, Lieutenant General Krafft von Dellmensingen had served in the

Dolomites in 1915 and seen the emergence of fast-moving assault tactics against

Romania. He now prepared a plan to drive the Italian Second Army some 40

kilometres back from the Isonzo to the Tagliamento and perhaps beyond,

depending on the breakthrough and its collateral impact on the lower Isonzo. It

was not intended as a fatal blow; the Germans believed the Italians were so

dependent on British and French coal, ore and grain that nothing short of total

occupation – which was out of the question – could make them sue for peace.

Success would be measured by Italy’s inability to attack again before the

following spring or summer.

The first target was a wedge of mountainous territory, five

kilometres wide between Flitsch and Saga (now Žaga) in the north, then 25 kilo

metres long, from this line to the Austrian bridgehead at Tolmein. The little

town of Caporetto lies midway between Saga and Tolmein, near a gap in the

Isonzo valley’s western wall of mountains. This breach, leading to the lowlands

of Friuli, gave Caporetto a strategic importance quite out of proportion to its

size. This had been recognised a century earlier by Napoleon, when he warned

his commander in Friuli that if the Austrians broke through here, the next

defensible line was the River Piave. South of Caporetto, the valley is a

kilometre wide; northwards, the river snakes through a gorge of cliffs and

steep hillsides, then broadens again at Saga, where the river angles sharply eastwards.

At Flitsch, the valley splays open like a bowl, flanked on the north by Mount

Rombon.

Since Austrian military intelligence had cracked the Italian

codes earlier in the year, the Central Powers were well informed about enemy

dispositions in this labyrinth of ridges rising 2,000 metres, where

communications were ‘as bad as could be imagined’. Krafft thought the Italian

defences were so shallow that losing this wedge of ground could crack open the

front from Gorizia to the Carnian Alps. Eight to 10 divisions at Tolmein and

three more at Flitsch should suffice. As at Riga, the artillery would deliver a

very violent bombardment, then support the assault by laying down box barrages

to isolate enemy units.

Hindenburg created a combined Austro-German force for the

purpose, the Fourteenth Army, led by a German general, Otto von Below, with

Krafft as his chief of staff. Seven German divisions, all of high quality,

would join the three Austrian divisions already on the ground plus an

additional two from the Eastern Front, backed by a reserve of five divisions: a

total of 17 divisions, supported by 1,076 guns, 174 mortars and 31 engineering

companies. It was an Austrian general who proposed applying the new tactics.

Alfred Krauss, appointed to command a corps at the northern end of the sector,

argued that the attack should proceed along the valley floors, avoiding the

high ridges in order to isolate and encircle them. He had made a similar

proposal to Conrad in 1916, in vain. This time, his advice was taken. For Cadorna,

obsessed with attacking high ground and retaining it at all costs, this

proposition would have made no sense. Yet it was appropriate to the terrain

north of Tolmein, where the mountain ranges loosely interlock, with the Isonzo

threading between them.

The attack was scheduled for mid-October, leaving only five

or six weeks to prepare. The roads from the assembly areas beyond the Alps were

few and poor, especially from the north; two passes linked Flitsch to the

Austrian hinterland, but the roads were narrow. Fortunately the Austrians had a

railhead near Tolmein. Some 2,400 convoys brought 140,000 men, a million and a

half artillery shells, three million fuses, two million flares, nearly 800

tonnes of explosive, 230,000 steel helmets, 100,000 pairs of boots, 60,000

horses. Then October brought its downpours. The sodden roads sagged under the

ceaseless traffic of boots, wheels and hooves. By veiling the massive

concentration, however, the bad weather served the Central Powers well. The

Germans went to great lengths to keep their presence secret. Transports arrived

by night, some units wore Austrian uniforms, others were taken openly to

Trentino then secretly moved eastwards. Fake orders were communicated by radio.

The Austrian lines on the Carso, 40 kilometres away, were ostentatiously

weakened to deter the Italians from transferring men northwards. The German air

force, brought in for the first time, photographed the Italian lines and

prevented Italian planes from overflying the Austrian lines. The gunners bracketed

their targets over a six-day period, to avoid alerting the enemy.

If the Italian observers noticed nothing unusual, this was

partly because they expected the front to remain quiet until spring 1918.

Austrian deserters talked about an attack in the offing, but their warnings

were ignored. By the 24th, the Central Powers had a huge advantage in

artillery, trench mortars, machine guns and poison gas on the upper Isonzo, and

roughly a 3:2 superiority in men. The Germans crouched like tigers, ready to spring.

As for the Austrians, far from being demoralised by sharing their front, they

were inspired by the scale of German involvement. Without knowing the whole

plan, the troops realised something big was up. The possibility of moving

beyond the hated mountains stirred their hearts.

On 18 September, Cadorna put the forces on the Isonzo front

on a defensive footing. Without ensuring that his order was implemented, he let

himself be absorbed by other matters. He was incensed to discover that Colonel

Bencivenga, his chef de cabinet until the end of August (and who was so

unhelpful over the Carzano initiative), had criticised his command in high

places in Rome. This mattered because Cadorna’s Socialist and Liberal critics

were finally making common cause, preparing to challenge his command when

parliament opened in mid-October.

He was also vexed by an article in an Austrian newspaper.

Cadorna filed every press clipping about himself, with references underlined in

crayon. Several months earlier, a Swiss journalist had written that the

Austrian lines on the Isonzo were impregnable. After the Tenth Battle, Cadorna

sent his card to the journalist with a sarcastic inscription: ‘With spirited

compliments on such penetrating prophecies about the strength of the Austrian lines,

and hopes that you will never desist from similar insights.’ The insecurity

betrayed by this gesture swallowed more urgent priorities. Now he did it again.

A provincial newspaper in the Tyrol had commented that Cadorna wasted the first

month after Italy’s intervention in May 1915. This criticism was too painfully

true to pass; Colonel Gatti had to prepare a rebuttal explaining to readers in

Innsbruck that Cadorna had not wasted even a day. (Would his revered Napoleon

have written to an English provincial newspaper to explain why he decided not

to invade Britain?)

Then he went on holiday with his wife near Venice. The rain

was so heavy that he returned early, on 19 October, ‘in excellent spirits:

calm, rested, tranquil’. By this point, the Supreme Command had been aware for

at least three weeks that an attack was imminent on the upper Isonzo. The

presence of Germans was rumoured. Even so, Cadorna’s staff did not take the

threat seriously. The Austrians had never launched a big offensive across the

Isonzo; why would they do so now, with winter at the door?

As late as 20 October, Cadorna did not expect an Austrian

offensive before 1918. On the 21st, two Romanian deserters told the Italians

the place and time of the attack. They, too, were ignored. Next day, Cadorna

escorted the King to the top of Mount Stol, one of the ridges above Caporetto

that link the Isonzo valley to Friuli. They agreed there was no reason to

expect anything exceptional. On the 23rd, he predicted there would be no major

attack, and said the Austrians would be mad to launch operations out of the

Flitsch basin. Even on the morning of the 24th, when the enemy bombardment was

under way, Cadorna advised his artillery commanders to spare their munitions,

in view of the attack on the Carso that would inevitably follow. Rarely has a

commander been exposed so completely as the prisoner of his preconceptions.

What Clausewitz called ‘the flashing sword of vengeance’ was poised above his

head, and he was unaware. He had little idea what was going on in the minds of

his own soldiers; imagining the enemy’s intentions was far beyond him.

At 02:00 on 24 October, the German and Austrian batteries

opened up along the 30-kilometre front. The weight and accuracy of fire were

unprecedented, smashing the Italian gun lines, observation posts and

communications, ‘as if the mountains themselves were collapsing’. According to

Krafft von Dellmensingen, even the German veterans of Verdun and the Somme had

seen nothing like it. Rather than softening up the enemy, the purpose was to

atomise the defence. It succeeded with terrible effect, helped by fog and

freezing rain, and more significantly by Italian negligence. For the lines on

the upper Isonzo were in a sorry state.

After 18 September, the Duke of Aosta put Cadorna’s order

into effect on the Carso, placing the Third Army on the defensive. The lines

after the Eleventh Battle were incomplete in many places and lacked depth in

most. Batteries had to be moved to less vulnerable locations. Communications

along and between the lines were poor, especially at the juncture of command

areas; they had to be improved. These humdrum tasks also awaited the Second

Army, by far the biggest Italian force, deployed between Gorizia and Mount

Rombon. Yet its commander, General Capello, was reluctant; he convened his

corps commanders and paid lip-service to ‘the defensive concept’ while urging

them to hold ‘the spirit of the counter-offensive’ ever-present in their minds.

Capello enjoyed a mystical turn of phrase, and what he meant here was not

clear. Probably Krafft von Dellmensingen was right when he wrote in his memoirs

that Capello had no idea what was meant by a modern defensive battle. He

followed up with an order that his commanders must convince the enemy of ‘our

offensive intentions’. Again, Capello wanted to go his own way, and again

Cadorna shrank from confronting him.

This confusion was most harmful on the Tolmein–Rombon

sector, which was woefully undermanned. Of the Second Army’s 30 divisions,

comprising 670,000 men, only ten were deployed north of the Bainsizza plateau.

The northern sector had seen little significant action since 1916, and the

Supreme Command judged that the mountains formed their own defence. For the

same reason, none of the Second Army’s 13 reserve divisions was located north

of Tolmein. East of the Isonzo, the troops were concentrated in the front line,

depriving the second and third lines of strength, while the mountainous terrain

would make it difficult to bring reserves forward, even supposing they could be

transferred in time to be effective.

Despite these defects, nothing much was done until the

second week of October. By this time, Capello was laid low with a recurrent

gastric infection and nephritis. Sometimes he relinquished command and retired

to bed or to a military hospital in Padua. This did not improve the efficiency

of his headquarters, however. With Capello breathing down his neck and the

Supreme Commander ignoring him, the interim commander’s grip was less than

assured.

Illness did not shake Capello’s conceit. On 15 October, he

was still talking about ‘the thunderbolt of the counter-offensive’. Four more

days elapsed before Cadorna unambiguously rejected his request for extra

reserves to bolster a visionary operation to push the Austrians back by six

kilometres. Another four days passed before Capello explicitly dropped the idea

of a counter-offensive. He did not commit himself to Cadorna’s defensive design

until late afternoon on 23 October: less than 12 hours before the start of the

Twelfth Battle. Incredibly, Cadorna failed to see that the practical unity of

his command had been compromised, perhaps beyond repair. There was no clenched

fist in charge of the army, as his father had insisted there must be. His worst

nightmare had come true, and he could not see it.

The weakest section of the front was strategically the most

important, around the Tolmein bridgehead. Commands were blurred; brigades and

regiments came and went, and commanding officers were shuffled like playing

cards. On the Kolovrat ridge and Mount Matajur, many units that faced the

German army on the afternoon of the 24th only reached their positions that

morning.

On 10 October, Cadorna ordered the 19th Division to move

most of its forces west of the Isonzo. This was significant, for the 19th

straddled the valley at Tolmein. The lines in the valley bottom, and on the

hills to the west, were in better shape than the lines further east. Cadorna

saw that the distribution of men and guns favoured offensive action, and wanted

this to be corrected without delay. As the 19th Division was part of XXVII

Corps, responsibility for implementing this order lay with the corps commander,

Pietro Badoglio. Since his men stormed the summit of Mount Sabotino in August

1916, Badoglio’s career had been meteoric, raising him from lieutenant colonel

to general within a year, making him the best-known soldier in the country

after Cadorna, Capello, the Duke of Aosta and D’Annunzio. Now, inexplicably, he

waited 12 days before implementing Cadorna’s critical order. When the Germans

attacked out of Tolmein, fewer than half of the division’s battalions were west

of the river, with an even smaller proportion of its medium and heavy guns.

Badoglio had ordered the valley bottom to be ‘watched’ (as distinct from defended)

by a minimal force. He had also instructed the corps artillery commander not to

open fire without his authorisation. Around 02:30 on 24 October, this commander

called for permission to fire. Badoglio refused: ‘We only have three days’

worth of shells.’ By 06:30, the telephone link between the corps commander’s

quarters and his artillery headquarters, five kilometres away, had been

destroyed. The artillery commander stuck to his orders, so there was no

defensive fire around Tolmein.

At the northern end of the sector, the Italians were tucked

into strong positions along the valley bottom between Flitsch and Saga. If

Krauss were to capture this stretch of the river and take the mountain ridge

beyond Saga, the Italians had to be rapidly overwhelmed. After knocking out the

Italian guns, the Germans fired 2,000 poison-gas shells into the Flitsch basin.

The gas was a mixture of phosgene and diphenylchloroarsine; the Italian masks

could withstand chlorine gas, but not this. Blending with fog, the yellowish

fumes went undetected until too late. As many as 700 men of the Friuli Brigade

died at their posts. Observers on the far side of the basin scanned the valley

positions, saw soldiers at their posts, and reported that the attack had

failed. The dead men were found later, leaning against the walls of their

dug-outs and trenches, faces white and swollen, rifles gripped between stiff

knees.

(In Udine, 40 kilometres from Flitsch, Cadorna rises at

05:00, as always, to find his boots polished and uniform ironed by his bedside.

After breakfasting on milk, coffee and savoyard biscuits with butter, he writes

the daily letter to his family. This morning, he remarks that the worsening

weather favours the defence. He is, he adds, perfectly calm and confident. At

the 06:00 briefing, he learns that the second line on the upper Isonzo is under

heavy shelling. He interprets the fact that there has been no assault as

support for his view that this attack is a feint, intended to divert attention

from the Carso.)

Zero hour was 07:30. The Austrian units spread into the

fogbound valley below Mount Rombon. There was not much fighting; the powerful

batteries at the bend in the river, by Saga, had been silenced. In

mid-afternoon, the Italian forward units on Rombon were ordered to fall back to

Saga after dark. With Austrians above and below them, their position was

untenable. After burning everything that could not be carried, the three alpini

battalions traversed the northern valley slopes while their attackers felt

their way south of the river.

The Austrians reached Saga at dawn on the 25th to find it

empty: the Italians had pulled back overnight to higher ground. For Saga guards

the entrance to the pass of Uccea, leading westward. The southern side of this

pass is formed by Mount Stol. The Italians hoped to block access to the Uccea

pass from positions on Stol. Daylight illumines the high ridges before the

valleys emerge from shadow. The Austrians entering Saga would look up at the

Italian positions on Stol, and know that very little stood between them and the

plains of Friuli.

It was a spectacular day’s work by the Krauss Corps. At the

other end of the wedge, around Tolmein, progress had been even more dramatic.

As we move there, let us pause over the sharp ridges that radiate like spokes

from Mount Krn, and look more closely at one of the batteries that stayed

silent on 24 October.