‘Caught on the Surface’. The sinking of U-461 by RAAF Sunderland “U” of 461 Squadron RAAF, in the Bay of Biscay in July 1943. [As depicted by aviation artist Robert Taylor.]

AIRCRAFT AVAILABLE

At the outbreak of war in September 1939 Air Marshal Sir

Frederick Bowhill, the Air Officer-in-Chief of Coastal Command, had forces of

ten Anson squadrons, including four Auxiliaries, one Hudson squadron, and two

strike squadrons of Vildebeests. The flying-boat units were two squadrons of

Sunderlands, three with Saro Londons, and one equipped with Supermarine

Stranraers. The Vildebeest strike-aircraft and the London and Stranraer

flying-boats were all obsolescent.

The Ansons represented the equipment for more than half his

total force, but with insufficient range to undertake the reconnaissance

required, and four out of the six flying-boat squadrons were equipped with

obsolescent aircraft. Sir Frederick was thus left with just three squadrons

with modern aircraft, namely Hudsons and Sunderlands, that were considered able

to operate effectively.

In the early months of 1939 supplies of engines for the Avro

Anson aircraft were limited, and there was a need to restrict the flying of

Ansons on that account. It was necessary also to conserve even the outdated

Vildebeests, as there were only six in store to supply both home and abroad. At

that time the Command had ten Stranraers, seventeen Londons, four Short

Singapore flying-boats, and two Sunderlands. Deliveries of the latter to the

Command were given as only two per month.

The Director of Organisation at the Air Ministry, then

Charles Portal, following the Munich crisis, foresaw what was to be a problem

in respect of the availability of aircraft throughout the war. That was that

aircraft could be weather-bound for days at various places round the coast.

Coastal Command was required to operate throughout the twenty-four hours, and

to do that bases were required for both take-off and landing with some degree

of safety. This applied particularly to flying-boats. The new twin-engined

flying-boat, the Saro Lerwick, had not been expected to be delivered before

April 1939, and therefore was unlikely to be operational before the end of the

year, but then it was to be found unsuitable for operations.

There was a need, therefore, for land-based aircraft to

cover the South-Western Approaches, and significantly, in the same memo of 25

October 1938, Portal refers to having Newquay (St Eval) laid out to take two

squadrons.

Between December 1939 and August 1940 the following

reinforcements were received by Coastal Command: No. 10 Squadron RAAF

Sunderlands in December 1939, four Blenheim squadrons on loan from Fighter

Command in February 1940 (Nos 235, 236, 248 and 254); in June 1940 Nos 53 and

59 Squadrons with Blenheims on loan from Bomber Command, and in August 1940,

No. 98 Squadron’s Fairey Battles, also on loan from Bomber Command, the latter

to be based in Iceland.

These additions had followed an agreement by the Air

Ministry with the Admiralty for Coastal Command to have an additional fifteen

squadrons by June 1941. By 15 June, that had only been achieved by the loan of

seven squadrons from other Commands, with aircraft unsuited to the maritime

role, and with a daily average availability of 298 aircraft.

Just a month later, the Command had 612 aircraft with

thirty-nine squadrons, but by then it was estimated that future requirements

would be sixty-three and a half squadrons with 838 aircraft. The 612 aircraft

then available included eleven types, and that would have produced problems in

training for aircrew when they converted to a different type of aircraft. At

Air Chief Marshal Sir Philip Joubert de la Ferté’s first staff meeting on 30

June as Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief Coastal Command, the number of aircraft

available was not stated, but rather that there were only four strike

squadrons.

By 1 December 1941 reconnaissance aircraft available to

Coastal Command included eighteen Catalina flying-boats, nine Sunderlands,

twenty Whitleys and 170 Hudsons. The Command’s strike aircraft comprised sixty

Beaufort torpedo-bombers, twenty Beaufort bombers and forty Beaufighters.

Additionally, Coastal had sixty of the Blenheim fighter version. The total of

397 aircraft was available to equip eighteen squadrons.

The total number of aircraft available to Coastal Command in

June 1942 was 496, and would have included aircraft of four squadrons on loan

from Bomber Command, but for Sir Philip, there was a shortage of three

landplane squadrons, and ten flying-boat squadrons; and in his report to the

Air Ministry he added: ‘I therefore cannot accept your view that we are

comparatively well off, nor do I feel that we have sufficient strength to carry

out our job.’

Although, in November 1942, Coastal had 259 Hudsons, Sir

Philip was concerned about their availability, due to ten squadrons plus other

units still operating them, and stated that with the ‘present Hudson commitment

… continuance of the present numbers of squadrons is impossible’.

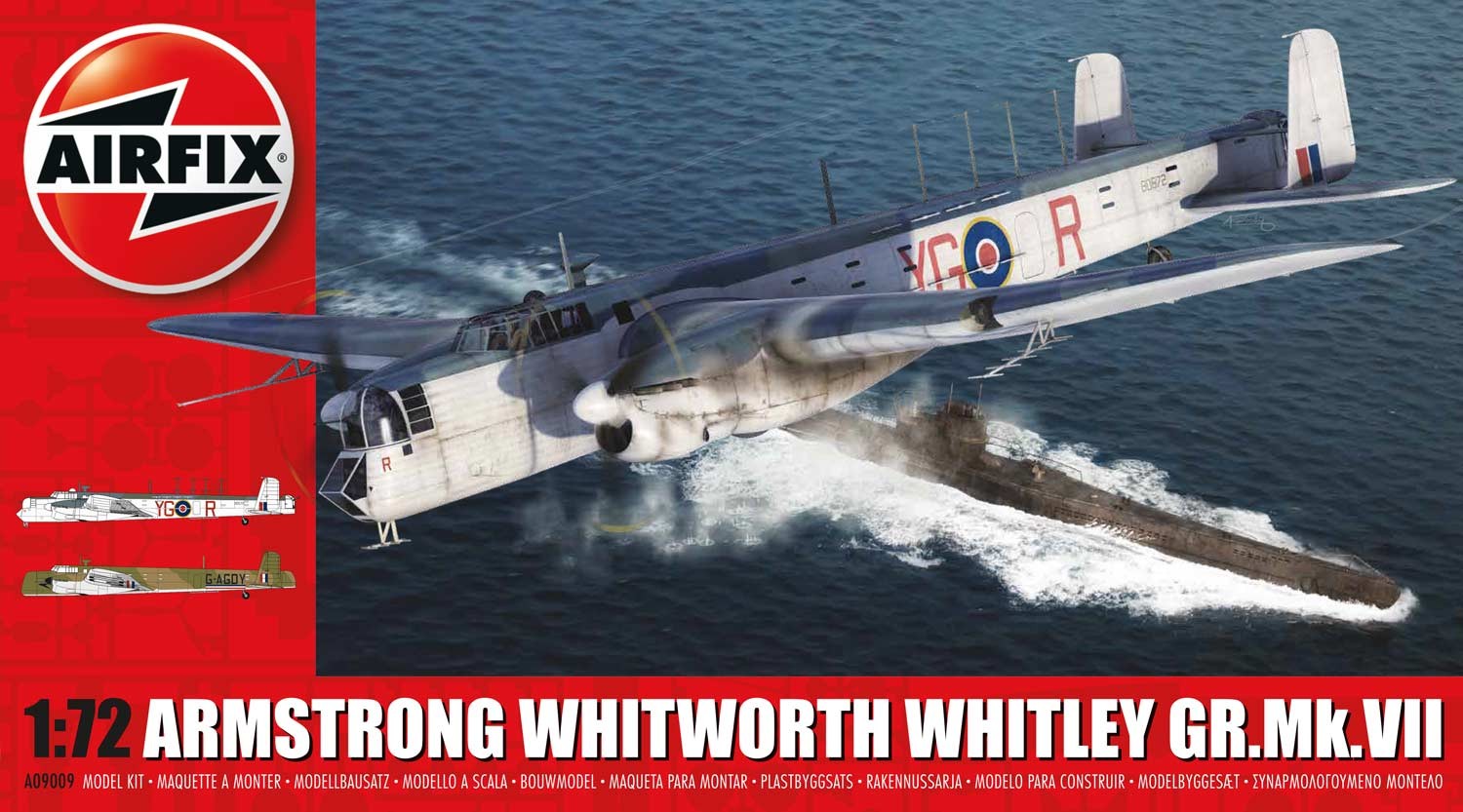

Sir Philip was still concerned about the two types from

Bomber Command, such as the Whitley, ‘… on the whole, given unsatisfactory

service’ and the Hampden, which was ‘incapable of operating in daylight … off

the enemy coast … without a very strong escort of long-range fighters’.

There were no Beaufort-equipped squadrons left with Coastal

Command (they were posted overseas), and no trained Beaufighter squadron, and

it was known that German Fw190 fighters were 50 mph faster than the

Beaufighter, which was therefore hardly suitable as escort to the Hampdens even

if available.26 De Havilland Mosquitoes had been made available for

Photo-Reconnaissance in 1942, but for the Mosquito Mark VI fighter-bomber

priority was given to Fighter Command.

When Air Marshal John Slessor assumed command of Coastal

Command in February 1943, the strength was sixty squadrons with ‘some 850

aircraft’. Although he appeared largely content with the aircraft available to him,

in respect of both quantity and quality, he wrote to the Air Ministry in

September stating, ‘I now find that there are 120 first line Mosquitoes going

into photo-reconnaissance in this country, and over 200 first line Mosquitoes

going to the Army support in the Tactical Air Force’.

Thus, despite the need for reconnaissance, priority was

given to the TAF. He refers, however, to the ‘unforeseen requirement for

modification of certain four-engined types to Very Long Range [VLR]’ coinciding

with the introduction of a system of ‘planned flying and maintenance … in what

was a “difficult period of availability”’.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Sholto Douglas succeeded Air Marshal

Slessor in January 1944, when, in respect of numbers of aircraft, equilibrium

had obviously been reached. The Command’s records written during his tenure

refer to equipment of aircraft such as ASV, and modifications to aircraft

rather than the need for more aircraft. Forces for Sholto Douglas included

(again, as was the case for Slessor) 430 aircraft for anti-submarine

operations.

The 430 aircraft, however, were the equipment for ten

squadrons of Liberators, including three of the United States Navy; five

Leigh-Light Wellington squadrons, and two squadrons each equipped with

Halifaxes, Hudsons and Fortresses. There were also seven Sunderland and two

Catalina squadrons. The heavy four-engined aircraft that Sir Sholto then had

available did, however, raise another requirement–the need for runways of

sufficient length to take such as the Liberator, Fortress and Halifax.

Thus, on 7 February 1944, the Air Ministry was asked to

approve the lengthening of the runways at Brawdy, Chivenor, Aldergrove and

Leuchars. Although Sholto Douglas expressed no need for more aircraft, he

referred to the ‘Bomber Baron’s decision finding the Liberator unsuitable for

night operations’, such that Coastal Command’s near starvation came to an end’.

He added, ‘By the time that I became C-in-C of Coastal we were using twelve

squadrons of them.’

However, by 27 April the Command was obviously preparing for

Operation Overlord–the invasion of Europe, and a signal was sent to No. 19

Group regarding the necessity for ‘reducing wastage to conserve aircraft for

forthcoming operations’. Specifically mentioned were Mosquitoes and Liberators.

In November the re-equipment of Halifax squadrons with

Liberators was again mooted, although these were all bombers that had to be

modified for Coastal Command.

In 1945 the Air Ministry agreed to thirty Mark V Sunderlands

(those with Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines), which had been intended for

overseas service, to be allocated to Coastal Command. This was in sharp

contrast to Sir Philip Joubert’s experience three years earlier, when he was

losing both aircraft and crews to overseas. During Sir Sholto’s final meetings,

a whole spectrum of aircraft types had to be considered. Thus, during the 4 May

meeting he asked the Senior Air Staff Officer to find from the Air Ministry

what the Command’s commitments might be for modifying fifty Gloster Meteor jet

aircraft for photo-reconnaissance, and those required for the Supermarine Sea

Otter.

AIRCRAFT REQUIREMENTS

Until the outbreak of the Second World War the number of

aircraft considered necessary for Coastal Command to provide trade protection

in Home Waters was 281. This number assumed a war by Britain alone against

Germany. The prime duty was then to cover the exits from the North Sea.

The capitulation of France, the over-running of the Low

Countries and the occupation of Norway and Denmark resulted in a vast coastline

from the French Biscay ports to North Cape to be covered. The entry of Italy

into the war in addition to a possible hostile French fleet made further

demands on Coastal Command. Thus, in addition to covering the North Sea exits,

three additional flying-boat squadrons were considered to be immediate

requirements to cover the Irish Sea, Faeroes areas, and Western Approaches,

plus an additional general reconnaissance landplane squadron and two long-range

fighter squadrons–say, another 100 aircraft.

For overseas, an additional five flying-boat squadrons and

one landplane squadron were specified; thus, for additional home and overseas

commitments, possibly 200 aircraft above the 281 already stated were needed.

This assumed that other forces would cover the Caribbean and Newfoundland

areas. In December 1939, however, the Command was concerned with close escort

of coastal convoys and the chain of patrols to the Norwegian coast.

For those duties reference was made specifically to two

types of aircraft, the Avro Anson and the Lockheed Hudson, the reconnaissance

landplanes then available. With those two types, a total of 273 aircraft was

anticipated, following an agreement to increase the requirements of each

squadron to twenty-one aircraft. Other landplanes for reconnaissance then being

considered about that time were the Blackburn Botha, the Bristol Blenheim and

Bristol Beaufort, with the comments that the Botha was ‘specially designed for

reconnaissance’, but that the Blenheim was ‘adversely reported’. It was hoped

that twenty Bothas would be delivered to the Command by the end of 1939, and

twelve Beauforts were expected in October/November.

The Bothas, however, were found unsuitable for operations,

and no more of the Mark IV Blenheims were being allocated to Coastal Command.

In October 1941 the Prime Minister became aware of U-boats

operating further afield, and suggested to the First Lord of the Admiralty that

it was probably due to our air operations. Following this, Coastal Command’s

requirement programme was considered to be 150 Catalinas and seventy-two

Sunderlands for twenty-six flying-boat squadrons; thirty-two Liberators and

thirty-two Wellingtons or Whitleys to equip four long-range GR squadrons;

sixty-four Mosquitoes and 180 GR Hudsons for fifteen and a half medium- and

short-range squadrons; 128 Beauforts for eight torpedo-bomber squadrons; and

160 Beaufighters for ten long-range fighter squadrons. However, four

flying-boat and two GR short-range squadrons were to be earmarked for West

Africa, and three flying-boat squadrons for Gibraltar.

By December 1941 the types of aircraft required were stated

as a long-range flying-boat, a long-range landplane, a medium-range landplane,

a high-speed reconnaissance landplane, a long-range fighter, and a torpedo- bomber.

Changes had been made to requirements following the previous three months’

experience and an analysis of U-boat attacks. At that time it was considered

that extra-long-range aircraft should have a range of 2,000 miles because some

U-boat attacks had been 700 miles from British bases, and if air patrols were

deployed 350–600 miles, the enemy would move to the 600–700-mile area (600

miles from a United Kingdom base would be up to 20’E 15’W; from Iceland, up to

40’E 12’W).

Reconnaissance aircraft were then expected to have ASV

(Aircraft-to-Surface Vessel) radar for homing; long-range planes were to be

able to operate in all weathers and have a short take-off and landing distance.

For high-speed reconnaissance aircraft the Air Ministry suggested the Mosquito,

but other services were given priority in their supply.

Three types were suggested to undertake the task of a

torpedo bomber: the Handley-Page Hampden, the Bristol Beaufort and the Vickers

Wellington III.

All three were to operate as such, despite the lack of

forward armament in the Hampden and Beaufort, and the Wellington and Hampden

had not been designed for maritime work.

In early 1942 the functions of the Command’s operational

aircraft were clearly stated in six categories. Anti-submarine warfare was

first in order of importance, covering reconnaissance, depth-charging and

bombing. Second and fifth were torpedo warfare (reconnaissance and the attack

on large merchant vessels and enemy naval forces) and anti-shipping warfare

(reconnaissance and bombing). Third, fourth and sixth in order of importance

were photo-reconnaissance, meteorological reconnaissance and coastal fighter

warfare.

Coastal fighter and anti-shipping warfare were rated former

RAF peacetime functions; anti-submarine warfare had become a highly specialised

category, as also torpedo warfare. Little consideration had been given to the

latter, as it was ‘uneconomical to have torpedo squadrons locked up for a

target which may never materialise so may find ourselves making more use of the

GR/TB squadrons for GR work’, as was the case with Beauforts.

At the time of Air Marshal John Slessor assuming command of

Coastal in February 1943, the trend (which is reflected in the Command’s

records) was concerned about the equipment then being added to aircraft, rather

than the aircraft itself. This was resulting in an effect on the aircraft’s

range due to the additional loads–a matter of concern throughout the war.

Slessor addressed this matter in a letter to all his Group’s headquarters in

May 1943.

RANGE

Range of aircraft for a given design is affected by many

factors, such as the all-up weight, the quantity of fuel carried and the type

of engine(s). When airborne, other factors include the height at which the

aircraft is flown (this because the engines would be designed for an optimum

height for greatest efficiency).

Other factors for Coastal Command’s aircrew to consider were

whether they should deploy side guns in, for example, Wellingtons or Hudsons;

and in the case of the Sunderland flying-boats, whether they should run out

their depth charges onto the wings from the bomb-bay.

These were continuing tactical problems in addition to the

reduction of speed and range. All four of Coastal Command’s Air Officers

Commanding-in-Chief show their awareness of the importance of range for

aircraft in the Second World War–notably Sir Philip Joubert –who imposed a

limit on the endurance for crews of eighteen hours; and even that figure was to

be under exceptional circumstances. At RAF Waddington in April 1998, it was

understood that the endurance of aircrew is still the deciding factor in

maritime operations, albeit due to toilet facilities.

Although given as having an endurance of 5½ hours at 103

knots, the Anson represented the operational equipment for Coastal Command’s

land-based reconnaissance squadrons at the outbreak of war, excluding No. 224,

which had just rearmed with Hudsons. The Anson’s lack of range precluded it

being effectively used, even for the Command’s prime task on the outset of war,

reconnaissance from Britain to Norway. As Capt T. Dorling, RN, stated: ‘Ansons

were unable to reach Norway and blockade the North Sea. Only flying-boats and

Hudson squadrons were able to do so.’

The Air Ministry, when writing to the C-inC of Coastal

Command in September 1941, stated that a limit should not be set on the range

of reconnaissance aircraft, but that the matter would be pursued with the

Admiralty with a view to limiting the maximum operating distance from base of

600 miles, as convoy escorts beyond that would be uneconomical. Range was

necessary to cover, in particular, convoy routes, notably out into the North

Atlantic as far as the ‘prudent limit of endurance’, or ‘PLE’.

If on a ‘sweep’, that would have sufficed; but if a convoy

was to be escorted, say, at 12°W, it was essential also to have some hours in

that area circling the convoy; endurance was therefore also required. Opinions

vary in what was considered a useful time with a convoy, but typically two to

three hours. In a letter dated 28 July 1941, however, from Air Commodore Lloyd,

the Deputy SASO, it was recommended that at least one-third of sorties should

be with the convoy.

In Coastal Command, it was decided that the limit of

long-range aircraft should be the endurance of the crew rather than the fuel

supply. This was decided at a Command meeting on 7 January 1942, when Catalinas

were considered able to have a radius of 600 nautical miles, ‘on the fringe of

the U-boat area’, with a sortie of eighteen hours’ duration.

Sir Philip Joubert decided that routine patrols should not

exceed fourteen hours, but in cases of emergency could be extended up to

eighteen hours due to ‘conditions of cold and cramp in which the crews are

called upon to operate, and the need for sparing their endurance and not

stretching it to the limit unless an emergency arises’.

As an economy measure in Coastal Command’s use of Catalinas

in respect of long-range work, it was suggested by the Deputy Senior Air Staff

Officer (D/SASO) that Sunderlands could be used for sorties between 250 and 440

nautical miles along convoy routes. It is not clear, however, if that idea was

followed.

Range was considered so important that the question of

Liberators with or without self-sealing fuel tanks was raised, as without them

there would be a reduction of unladen weight but an increase in fuel capacity.

In January 1942, however, the Mark I Liberator’s maximum range is stated as

2,720 miles, but with the crew’s endurance limiting it to 2,240 miles.

When the Liberator was just coming into service with Coastal

in June 1941 for antisubmarine warfare, the C-in-C wrote to the Air Ministry:

For duties of this nature, which involve flying for long

periods by day and night, out of sight of land in all conditions of weather,

the Long Range bombers do not provide the same amenities and freedom of

movement to the crew as a flying-boat. The Liberator, which is being provided

for one squadron, meets these requirements to a greater extent than any

existing British bomber ….

He added, however, that more attention should be given to

their layout for reconnaissance rather than bomb load.

The long range of 2,240 miles enabled the Liberator in

Coastal Command to help close the ‘Mid-Atlantic Gap’ south of Cape Farewell

with such as a shuttle service between Newfoundland and Iceland.

Sir Philip Joubert stated that his first problem when he

succeeded Sir Frederick Bowhill in 1941 was ‘the need to fill the Gap’, and

here the only land-based aircraft that could do the job was the American B24,

the Liberator. The C-in-C Coastal Command in a review of the Command’s

expansion and re-equipment programme dated 12 June 1941 wrote: ‘The extension

of unrestricted U-boat warfare against shipping in the Atlantic to areas

outside the range of MR [medium-range] aircraft has necessitated the use of LR

[sic]

bombers such as the Whitley and Wellington as anti-submarine aircraft.’

The twin-engined medium bombers that came from Bomber

Command, the Wellington 1C and Whitley V, were both serving in Coastal by late

1940. Although they helped to fill a gap in the Command’s general

reconnaissance requirements, Air Commodore I.T. Lloyd, the D/SASO, wrote to the

C-in-C Coastal Command on 28 July 1941: ‘Whitleys and Wellingtons are

uneconomical at their speed and with only nine-hour sorties; we require a

replacement for these types to give range up to 600 miles … or at least 440 miles.’

Four-engined bombers that were loaned or allocated to

Coastal Command included the British Handley-Page Halifax and the Avro

Lancaster, but the Halifax when used for meteorological flights was provided

with drop tanks to increase the range.

By 30 November 1944 Coastal Command was due to receive

Pathfinder-type Mk III Halifaxes from Bomber Command’s production, but it was

considered necessary for the first one to be examined and modified at Gosport

to bring it up to the Command’s standard. When No. 502 Squadron was due to

re-equip with Halifaxes they were to be fitted with long-range tanks,

compensated, apparently, in respect of all-up weight, by having the front

turret removed.

This was despite the fact that when considering the

provision of Halifaxes for No. 58 Squadron, it was stated that for operations

in the Bay of Biscay front turrets were needed, largely against enemy fighters.

These essentially bomber aircraft were nevertheless operated

by Coastal Command in anti-submarine warfare, and for meteorological flights

and anti-shipping sorties. The Avro Lancaster, another four-engined bomber, was

only on brief loan to Coastal Command during the war, and does not feature in

the RAF’s official history as a Coastal Command aircraft. With a range of 2,350

miles it could have been invaluable, but the Chief of Air Staff was strongly

opposed to Lancasters being transferred to Coastal Command, as it was the only

aircraft able to take an 8,000 lb bomb to Berlin.

The American-built B17 Flying Fortress was rated a

long-range aircraft, but was selected for Coastal Command because it was

considered unfit for Bomber Command’s night operations. The Fortress served as

a useful reconnaissance aircraft with such as Nos 59, 206 and 220 Squadrons;

fortunately it was not required by Bomber Command, and it was reported on 27

January 1942 that all Fortress aircraft from America would go to Coastal Command.

The C-in-C Coastal Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Philip

Joubert, wrote to the Air Ministry on 7 January 1942 of his concern that his

long-range aircraft, ‘except the Liberator, fall far short of Coastal Command’s

needs … when U-boat attacks on shipping were about 700 miles westwards with

Catalinas at 600 miles only on the fringe of the U-boats’ area’. In that same

letter, Sir Philip referred to the medium-range Hudson as a ‘stop gap’ with the

Ventura [a development of the Hudson] of lesser range; that a medium-range

aircraft should have a range of 1,200 nautical miles, while the Wellington and

Whitley ‘more nearly meet requirements’. The Air Ministry’s ultimate response

was in a letter dated 7 March 1942, which stated:

It would be uneconomical to divert a successful heavy

bomber type to a Coastal Command role particularly if … a less successful

type of heavy bomber is available … the Fortress … is unfit for night

bomber operations and weather conditions strictly limit its employment … in high

altitude bombing … for these reasons it was selected for … Coastal Command.

The Air Ministry did show some appreciation of Coastal

Command’s requirements, but indicated the priority given to Bomber Command

with:

We should hamper the normal evolution of GR [general

reconnaissance] aircraft by setting a limit to their range. It is now apparent

that our requirements for heavy bomber types are unlikely to be realised in

full for a very long time. It will therefore be impracticable to provide many

squadrons equipped with this type for general reconnaissance work. Consequently

this role will have to be fulfilled by normal GR landplanes for some time to

come.

The Air Ministry added that the matter would be pursued with

the Admiralty, with Coastal Command aircraft limited to a radius of 600 miles;

greater distances ‘should be the responsibility of surface forces’.

At Sir Philip Joubert’s fifth staff meeting,

photo-reconnaissance aircraft were said to be Coastal’s ‘weak point’, and he

stated, ‘We must have long-range Spitfires.’ For both the Beaufighter, and

later the Mosquito, attempts were made to increase their endurance and range by

the addition of drop tanks. For the Mosquito, modifications are recorded from

November 1941 until towards the end of the war.