The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had a large carrier force at

the start of the war, the air groups of which were weighted toward attack

aircraft rather than fighters. Its aircraft were lightly built and had very

long range, but this advantage was usually purchased at the expense of

vulnerability to enemy fire. The skill of Japanese aviators tended to

exaggerate the effectiveness of the IJN’s aircraft, and pilot quality fell off

as experienced crews were shot down during the Midway and Solomon Islands

Campaigns.

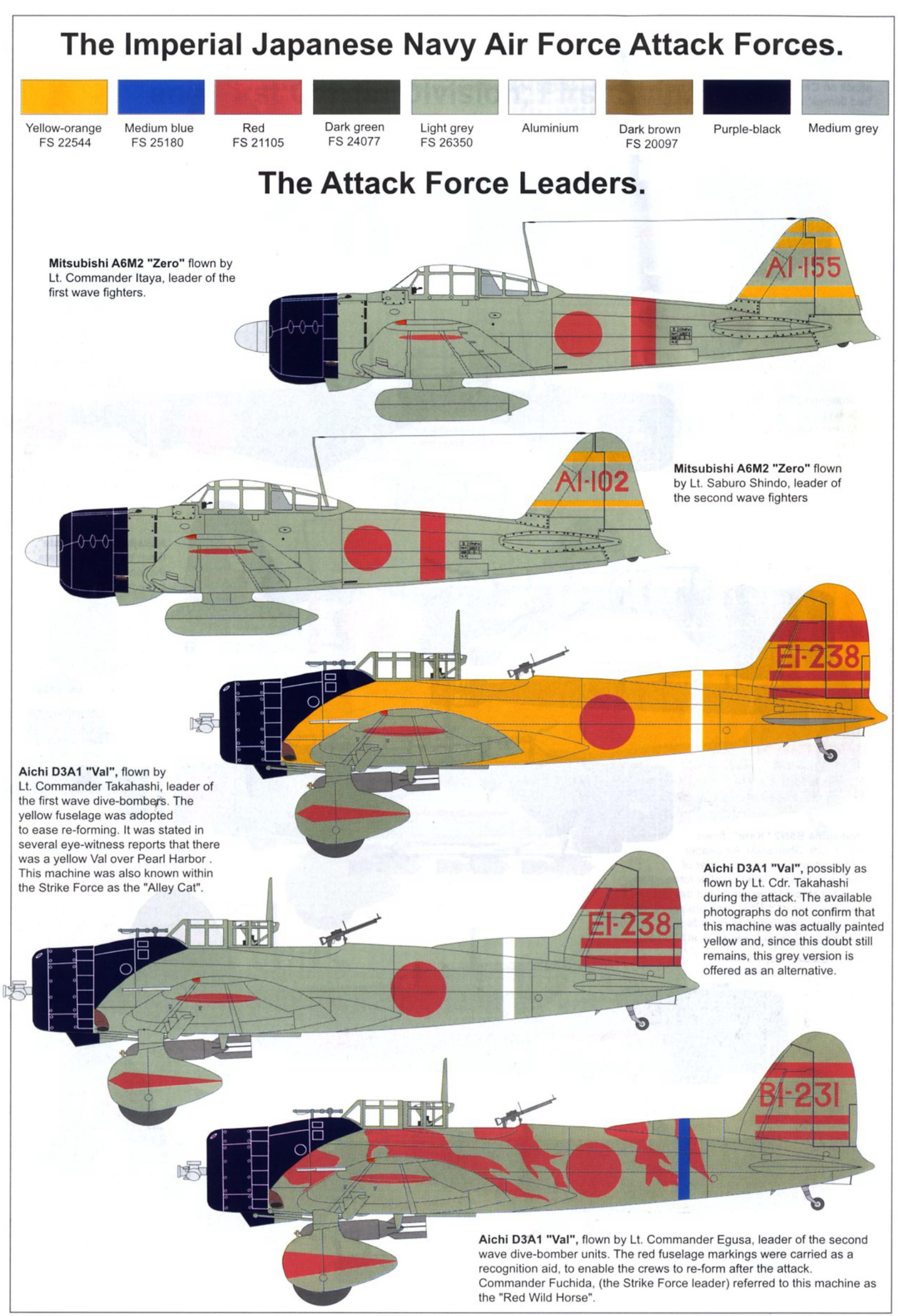

When it first appeared in mid-1940, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero

was the first carrier-based fighter capable of beating its land-based

counterparts. It was well armed and had truly exceptional maneuverability below

about 220 mph, and its capabilities came as an unpleasant shock to U. S. and

British forces. It achieved this exceptional performance at the expense of

resistance to enemy fire, with a light structure and no armor or self-sealing

tanks. Its Achilles heel was the stiffness of its controls at high speed, the

control response being almost nil at indicated airspeed over 300 mph. The Zero

was developed throughout the war, a total of 10,449 being built.

The Aichi D3A (“Val”) carrier-based dive-bomber entered

service in mid-1940, and it was the standard Japanese navy dive-bomber when

Japan entered the war. It was a good bomber, capable of putting up a creditable

fight after dropping its bomb load. It participated in the attack on Pearl

Harbor and the major Pacific campaigns including Santa Cruz, Midway, and the

Solomon Islands. Increasing losses during the second half of the war took their

toll, and the D3A was used on suicide missions later in the war. Approximately

1,495 D3As were built.

The Nakajima B5N (“Kate” in the Allied designator system)

first entered service in 1937 as a carrier-based attack bomber, with the B5N2

torpedo-bomber appearing in 1940. The B5N had good handling and deck-landing

characteristics and was operationally very successful in the early part of the

war. Large numbers of the B5N participated in the Mariana Islands campaign, and

it was employed as a suicide aircraft toward the end of the war. Approximately

1,200 B5Ns were built.

Japan relied on three primary reconnaissance floatplanes

during the war. The three-seat Aichi E13A, of which 1,418 were produced, was

Japan’s most widely used floatplane of the war. Entering service in early 1941,

it was employed for the reconnaissance leading up to the attack on Pearl

Harbor, and it participated in every major campaign in the Pacific Theater,

performing not only reconnaissance but also air-sea rescue, liaison transport,

and coastal patrol operations. Introduced in January 1944 as a replacement for

the E13A, the two-seat Aichi E16A Zuiun offered far greater performance

capabilities but came too late in the war to make a significant difference,

primarily because Japan’s worsening industrial position limited production to

just 256 aircraft. Based on a 1936 design that underwent several modifications,

the two-seat Mitsubishi F1M biplane, of which 1,118 were produced, proved to be

one of the most versatile reconnaissance aircraft in Japan’s arsenal. Operating

from both ship and water bases, it served in a variety roles throughout the

Pacific, including coastal patrol, convoy escort, antisubmarine, and air-sea

rescue duties, and it was even capable of serving as a dive-bomber and

interceptor.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the U. S. Pacific

fleet moved to this shallow harbor in Hawaii in May 1940, thousands of miles

from its base at San Diego. The idea was to deter a Japanese assault on

Southeast Asia. Instead, American-Japanese relations continued to deteriorate

toward war over the course of 1941. An Imperial Conference convened on

September 6 made the decision for war. Japanese forces immediately mobilized

and the Navy began planning the attack on Pearl. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

ordered preparations for the attack on November 1. A final peace effort by

Japanese diplomats failed in late November. A powerful warfleet, Strike Force

Kido Butai, sortied from the Kurils on November 26. It comprised six aircraft

carriers and many heavy escorts, destroyers, and submarines. The flagship of

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo flew the famous “Z” flag, which fluttered above

victories over Russia at Port Arthur in 1904 and the Tsushima Strait in 1905.

After 12 days undetected at sea, facilitated by refueling

from tankers, the carriers received the attack signal: “Climb Mount Niitaka.”

Washington had broken the Japanese diplomatic code but not the naval code.

Earlier in the day the War Department sent warnings to Pearl and Manila of an

anticipated Japanese assault. The attack, if it came, was expected to fall on

the Philippines; no one considered that the Japanese might be so daring as to

hit Pearl. In any event, the warning to Pearl was delayed by a black comedy of

technical and human errors and did not arrive in time. The battleships of the

U. S. Pacific Fleet were therefore still neatly docked on a quiet Sunday

morning and caught wholly unawares by the Japanese naval air attack. The first

attack wave achieved total surprise just after 7:00 A. M. on Sunday morning,

December 7th, 1941. It began before the official Japanese declaration of war

was delivered: it was delayed by lengthy transcription and slow decoding by the

Japanese Embassy in Washington. The declaration of war belatedly delivered to

Secretary of State Cordell Hull accused the United States of conspiring “with

Great Britain and other countries to obstruct Japan’s efforts toward the

establishment of peace through the creation of a new order in East Asia, and

especially to preserve Anglo-American rights and interests by keeping Japan and

China at war.” Americans later made much of the “sneak attack” at Pearl, though

in Japanese operational terms the achievement of surprise was desirable and

effective

Surprise over Hawaii was total. The attack was designed by

Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, a brilliantly innovative planner. It had as

historical inspiration the stunning sinking of the Tsarist fleet at anchor at

Port Arthur in 1904. Its spiritual inspiration and icon was even older: a

famous samurai sword maneuver, the “i-ia” stroke that gutted or crippled an

enemy before combat began. Its immediate progenitor was the RAF assault on the

Italian fleet at Taranto. Fuchida led in the first wave, comprising 183

bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters. Splitting into four attack groups, the

Japanese hit U. S. Army and Marine Corps air fields and bombed the ships lined

up in “Battleship Row” in the harbor at Ford Island. A second wave of 170

planes attacked into more opposition, yet Japanese losses remained light.

Within hours of the first explosions much of the Pacific Fleet was afire, sunk,

or badly damaged. Among major capital ships, the battleship “Arizona” was

gutted while the “Oklahoma” turtled. The battleships “California,” “Nevada,”

and “West Virginia” were also sunk at anchor. On these and other ships, at the

airstrips and elsewhere in Hawaii, the U. S. suffered 3,695 casualties, including

2,340 military personnel killed. Of the dead, 1,177 were aboard the “Arizona.”

Another 48 civilians were killed. The USN saw 12 of its warships sunk or

beached and another 9 badly damaged, while 164 Navy, Marine, or Army aircraft

were destroyed and 159 more damaged. The Japanese lost a mere 29 planes and 64

men, including 9 navy crew killed on 5 midget submarines. However, the U. S.

fleet carriers, the primary targets sought by Yamamoto and Fuchida, were

fortuitously at sea on exercises and thus were spared. The “USS Enterprise”

took some pilot casualties as it stretched its planes out from a distance to

intercept the Japanese second wave. Admirals Nagumo and Yamamoto then clenched

and refused to launch a third strike wave to destroy Pearl’s fuel and repair

facilities. Had they done so, that action would have done more long-term damage

to the Pacific Fleet even than dropping battleships in the shallow harbor.