Map of the Akkadian Empire (brown) and the directions in which military campaigns were conducted (yellow arrows)

Summerian King Lugalzagasi of Umma succeeded in establishing

his influence over all Sumer, although there is no evidence that he introduced

any significant changes. Twenty-four years later, the empire of Lugalzagasi was

destroyed by the armies of a Semitic prince from the northern city of Akkad,

Sargon the Great (2325-? b. c. e.) All Sumer was now united under the control

of the Akkadian king. Sargon bequeathed to the world the prototype of the

military dictatorship. By force of arms Sargon conquered all the Sumerian

city-states and the entire Tigris-Euphrates valley, bringing into being an

empire that stretched from the Taurus Mountains to the Persian Gulf and,

perhaps, even to the Mediterranean. In his fifty-year reign Sargon fought no

fewer than thirty-four wars. One account suggests that his army numbered 5,400

men, soldiers called gurush in Akkadian. If that account is correct, Sargon’s

army would have been the largest standing army of the period.

Sargon’s whole reign was spent in defending his empire from

the mountain people who raided Mesopotamia and from rebellions: he had to

mollify people who spoke different languages and lived in different cultures.

At first, he tried not to offend the Sumerians-when he needed land, he

purchased it-but in the end, in the face of continued rebellion, he took

stronger action: he levelled city walls and eliminated centers of resistance,

he garrisoned Sumer with Akkadian governors and Akkadian troops, and when still

he had not pacified Sumer, he confiscated tracts of land, expelled the

Sumerians, and resettled the land with Akkadians. Sargon had tried to treat the

Sumerians fairly, but his concept of fairness was radically different from

theirs-he believed that men appointed their rulers and men owned the land;

Sumerians believed that the gods appointed rulers and the gods owned the land

and, therefore, as they saw it, Sargon not only had no right to dismiss

Sumerian rulers or to dispose of their land, but he was committing sacrilege

when he did it.

Sargon discovered another limit to his conquests: although

he led his armies to the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, when he tried to

march them north into Anatolia, they mutinied and he was forced to turn back.

Sargon, like every ruler, depended upon the will of his army, and he accepted

the limits of what it would allow him to do in order to preserve its loyalty.

Because of the army’s loyalty Sargon was able to pass his empire on peacefully

to his son Rimush. Rimush, however, had to suppress a Sumerian revolt and nine

years after his accession he was assassinated. When his brother, the second son

of Sargon, succeeded him, he, too, had to suppress a Sumerian revolt, and he,

too, was assassinated. He was succeeded by his son, Naram-Sin.

Naram-Sin had to suppress a revolt by the Sumerians, the

revolt spread to the whole empire, and the perilous situation encouraged the

Gutians to invade Mesopotamia. Naram-Sin repulsed the Gutians, defeated the

rebels, took the title “king of the four-quarters” (that is, king of

the whole world), and announced to his subjects that he was a god. If the

Mesopotamians, and particularly the Sumerians, had accepted his claim (a not

impossible claim given that they believed that gods can grow old and die), then

(in logic) they would have been compelled to accept his right to confiscate

land and depose rulers. He failed, however, to convince them and never

reconciled the Sumerians to Akkadian rule.

Towards the end of Naram-Sin’s thirty-seven-year reign he again

had to stop a Gutian invasion, but this time he was unable to expel them from

his empire. He died, and his son inherited the continuing war against the

Gutians and, to compound his troubles, a new Sumerian revolt. The Sumerians

regained their freedom, the empire crumbled, and the Akkadian was driven back

to the confines of his home city, Agade. The Sumerians rejoiced in their

freedom, but not for long, because they quarreled with each other, they

overlooked the threat of the Gutians, and the Gutians invaded, conquered

Sumeria, and held it for a hundred years. The empire of Sargon and his heirs

was gone, but it left a legacy-all subsequent rulers in Mesopotamia dreamed of

re-creating Sargon’s empire.

In the midst of the twenty-second century a Sumerian hero,

the king of Uruk, drove the Gutians out of Mesopotamia and convinced the

Sumerians-with the help of his victory-to put aside their differences and unite

behind him. When he died in an accidental drowning, his successor, Ur-nammu,

took control of Sumer in one campaign, subjugated Akkad, took the title

“king of Sumer and Akkad” and characterized himself as “the son

of a god.” With the powers this divine status gave him (the right to

control the land and appoint the ensi’s), Ur-nammu dedicated himself to the

restoration of a ravaged and depressed land: he encouraged the reconstruction

of temples, city walls, roads, harbors, and, most important of all, the

irrigation system. Sumer became prosperous once more.

That Sargon’s army would have been composed of professionals

seems obvious in light of the almost constant state of war that characterized

his reign. As in Sumer, military units appear to have been organized on the

sexagesimal system. Sargon’s army comprised nine battalions of 600 men, each

commanded by a gir.nita, or “colonel.” Other ranks of officer

included the pa. pa/sha khattim, literally, “he of two staff s of

office,” a title which indicated that this officer commanded two or more

units of sixty. Below this rank were the nu.banda and ugala, ranks unchanged

since Sumerian times. Even if they had begun as conscripts, within a short time

Sargon’s soldiers would have become battle-experienced veterans. Equipping an

army of this size required a high degree of military organization to run the

weapons and logistics functions, to say nothing of the routine administration

that was characteristic of a literate people who kept prodigious records. We

know nothing definitive about these arrangements.

An Akkadian innovation introduced by Sargon was the niskum,

a class of soldiers probably equivalent to the old aga-ush lugai, or

“royal soldiers.” The niskum held plots of land by favor of the king

and received allotments of fish and salt every three months. The idea was to

create a corps of loyal military professionals along the later model of

Republican Rome. Thutmose I of Egypt, too, introduced a similar system as a way

of producing a caste of families who held their land as long as they continued

to provide a son for the officer corps. The Akkadian system worked to provide

significant numbers of loyal, trained soldiers who could be used in war or to

suppress local revolts. Along with the professionals, militia, and these royal

soldiers, the army of Sargon contained light troops or skirmishers called nim

soldiers. Nim literally means “flies,” a name which suggests the

employment of these troops in spread formation accompanied by rapid movement.

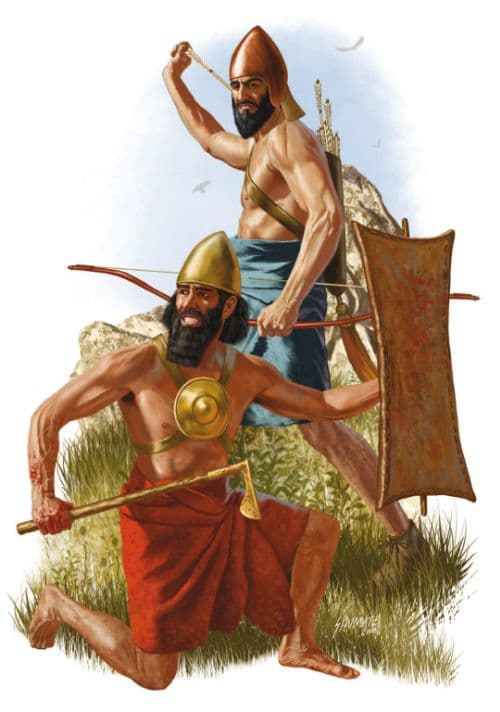

During the Sargon period the Sumerians/Akkadians contributed

yet another major innovation in weaponry: the composite bow. The introduction

of this lethal and revolutionary weapon may have occurred during the reign of

Naram Sin (2254-2218 b. c. e.), Sargon’s grandson. Like his grandfather, Naram

Sin fought continuous wars of conquest against foreign enemies. His victory

over Lullubi is commemorated in a rock sculpture that shows Naram Sin armed

with a composite bow. This sculpture marks the first appearance of the

composite bow in history and strongly suggests that it was of Sumerian/Akkadian

origin. The fact that the bow appears in the hand of the warrior king himself

suggests that it was a major weapon of the time, even though there is no

surviving evidence that the Sumerian army had previously used even the simple

bow.

The composite bow was a major military innovation. While the

simple bow could kill at ranges from 50 to 100 yards, it would not penetrate even

simple leather armor at these ranges. The composite bow, with a pull of at

least twice that of the simple bow, could easily penetrate leather armor and,

perhaps, even the early prototypes of bronze armor that were emerging at this

time. In the hands of even untrained peasant militia the composite bow could

bring the enemy under a hail of arrows from twice the distance of the simple

bow. So important was this weapon that it became a basic implement of war of

all armies of the Near East for the next 1,500 years.

The use of battle cars seems to have declined considerably

during the Akkadian period. Any number of reasons suggest themselves. Such

vehicles were very expensive. In Sumer a powerful king could commandeer the

cars of his vassals, which they maintained at their expense. But with the

centralization of political authority under Sargon these vassals disappeared,

making the cost of these cars a royal expense. The professionalization of the

army resulted in an infantry-heavy force which under most circumstances would

have required few battle cars beyond those needed to transport the king and his

generals. Finally, the Akkadian kings fought wars far from home in the

mountains of Elam and against the Guti farther north. These were lightly armed,

highly mobile enemies fighting in mountains and heavily wooded glens. The

chariot had come into being to fight wars between rival city-states on

relatively even terrain. Their use in rough terrain at considerable distances

from home probably revealed the battle car’s obvious deficiencies under these

conditions, leading to a decline in its military usefulness. They seem to have

remained in use by couriers and messengers at least within the imperial

borders, where they traveled regular routes known as chariot roads.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin.

The the most famous Akkadian martial monument, 24 this stele

shows the king and his army ascending into the Zagros Mountains and defeating

the Lullubu highlanders. This scene is the first in the history of Mesopotamian

martial art to attempt to depict the natural terrain of the battlefield in a

single scene rather than in stylized panels. The terrain shows a number of

ridges covered with trees and a high mountain peak in the background. The

inscription reads in part, “Satuni, the king of the highlanders of Lullubum

assembled together . . . [for] battle.. . . [Naram-Sin defeated them and]

heaped up a burial mound over them . . . [and] dedicated [this object, the

stele] to the god [who granted victory]” (R2:144). The Lullubu soldiers, with

their distinctive long braided ponytails, are shown in an utter rout. Several

lie dead; one has an arrow or javelin protruding from his neck. Another falls

from the mountain. Two more run away, one with a broken pike. The Lullubi king

Satuni stands before Naram-Sin, begging for his life. The Akkadian army, on the

other hand, marches boldly forward in good order. All six of the Akkadian

soldiers wear kilts and helmets, broadly similar to those shown in the earlier

Sumerian Standard of Ur and Stele of the Vultures. They all also have

narrow-bladed axes for melees. Two carry war banners, two hold 2.5-meter pikes

at the butt, resting the shaft on the shoulder like a rifle on the

parade-ground. The fifth Akkadian has a bow, while the sixth seems to have an

axe. The heroic Naram-Sin leads his army into battle on the crest of the

mountain, standing twice as tall as anyone else, and stepping on the bodies of

fallen enemies. He has a similar kilt, but has a thick beard and long hair, and

wears a horned crown symbolic of his divinity. In his hand he carries an axe, a

bow, and an arrow. His bow is often said to be the earliest representation of a

composite bow.