As a stopgap measure pending the Panthers’ design,

production, and delivery, Guderian’s commission had recommended upgrading the

army’s assault guns. About 120 of the Model IIIF with a 75mm L/43 had entered

service in 1942, prefiguring the assault gun’s development from an infantry

support vehicle into a tank destroyer. As a rule of thumb, the longer a gun,

the less effective its high-explosive round. From the infantry’s perspective,

however, the tradeoff was acceptable, and the Sturmgeschütz IIIG was even more

welcome because of its 75mm L/48 main armament. The effective range of this

adapted Pak 43 was more than 7,000 feet. It could penetrate almost 100mm of

30-degree sloped armor at half that distance. The IIIG took the original

assault gun design to the peak of its development by retaining the low

silhouette and improving frontal armor to 80mm by bolting on extra plates, all

within a weight of less than 25 tons. The family was completed, ideally at

least, with the addition of a 105mm howitzer version in one of the battalion’s

three ten-gun batteries to sustain the infantry support role.

The one-time redheaded stepchild of the armored force now

had a place at the head table. There had been 19 independent assault gun

battalions in May 1941. In 1943 that number would double. Constantly shifted

among infantry commands, their loyalty was to no larger formation. Continuously

in action, they developed a wealth of specialized battle experience that led

infantry officers to follow the assault gunners’ lead when it came to

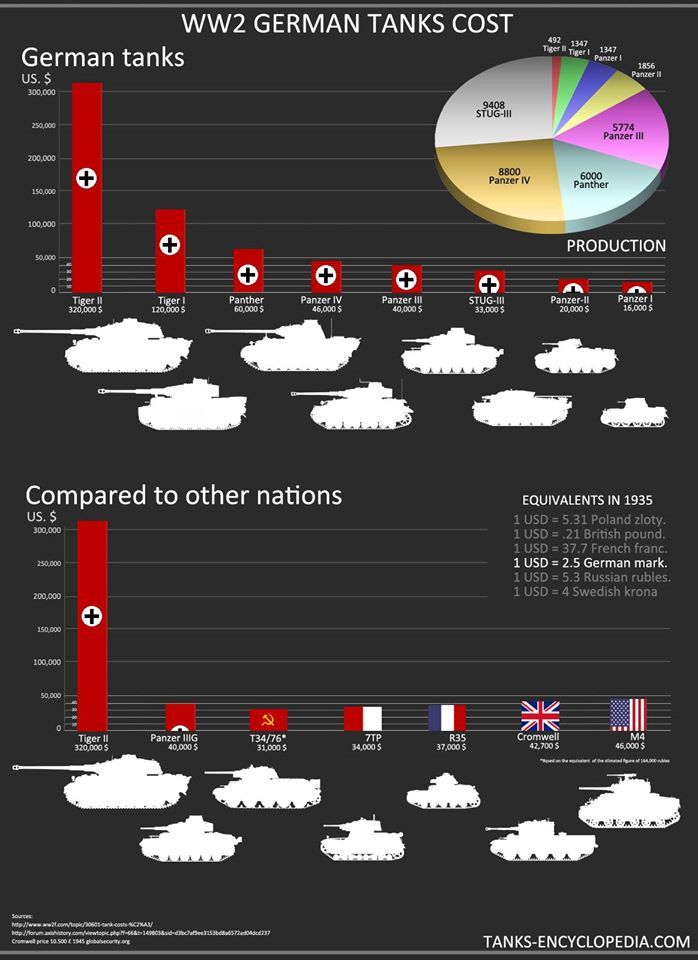

destroying tanks and mounting counterattacks. Assault guns cost less than

tanks. Lacking complex revolving turrets, they were easier to manufacture, and

correspondingly attractive in an armaments industry whose workforce skill and

will were declining with the addition of more and more foreign and forced labor

and the repeated comb-outs of Germans destined for the Wehrmacht.

Meanwhile, tank production was in the doldrums. The Panzer

III was so clearly obsolete as a battle tank that its assembly lines had been

converted to providing chassis for assault guns. By October 1942, production of

the Panzer IV was down to 100 a month. The General Staff recommended a leap in

the dark: canceling Panzer IVs and concentrating exclusively on Panthers and

Tigers. Previous outsiders like Porsche, and a new generation of subcontractors

turning out assault guns, were jostling and challenging established firms. But

the German automotive industry, managers and engineers alike, had from its

inception been labor-intensive and conservative in its approaches to

production. As late as 1925 the US Ford Motor Company needed the equivalent of

five and three-quarters days’ labor by a single worker to produce a car.

Daimler needed 1,750 worker days to construct one of its top-line models. When

it came to design, focus was on the top end of the market and emphasis was on

customizing as far as possible by multiplying variants. It was a far cry from

Henry Ford’s philosophy that customers could have any color they wanted as long

as it was black.

For their part, the civilian tank designers were

disproportionately intrigued by the technical challenges Panthers and Tigers

offered. They took apparent delight in solving engineering problems in ways

that in turn stretched unit mechanics to limits often developed originally in

village blacksmith shops.

One might suggest that by 1942 a negative synergy was

developing between an armored force and an automobile industry, each in its own

way dedicated to an elite ethos and incorporating an elite self image. The

designers were correspondingly susceptible to the dabblings of Adolf Hitler.

Previously, his direct involvement in the issue had been limited, his demands

negotiable, his recommendations and suggestions reasonable. The Hornet, for

example, combined the Hummel’s armored open-topped superstructure with the 88mm

L/71 gun Hitler had wanted for the Tiger. The vehicle’s bulky chassis made it

too much of a target to render feasible stalking tanks in the fashion of the

Marder and the assault guns. But its long-range, high-velocity gun was welcome

to the half dozen independent heavy antitank battalions that absorbed most of

the 500 Hornets first introduced in 1943.

The Ferdinand, later called the Elephant, was a

waste-not/want-not response to the Porsche drives and hulls prepared in

anticipation of the Tiger contract that went to Henschel. Hitler saw them as

ideal mounts for a heavily armored tank destroyer mounting the same 88mm gun as

the Hornet. Ninety were rushed into production in spring 1943 and organized

into an independent panzer regiment. Without rotating turrets, at best they

were Tigers manqué, with all the teething troubles and maintenance problems

accompanying the type and no significant advantages. At 65 tons, any

differences in height were immaterial. And the omission of close-defense

machine guns as unnecessary would too often prove fatal for vehicles whose

sheer size made them targets for every antitank weapon in the Red Army’s

substantial inventory when they were sent into action at Kursk.

The Hornet and the Elephant were mere preliminaries. Since

adolescence the Führer had liked his architecture grandiose, his music molto

pomposo, and his cars high-powered. In June 1942, he authorized Ferdinand

Porsche to develop a super-heavy tank: the Maus (“Mouse”—and yes, the name was

ironic). The vehicle carried almost ten inches of frontal armor, mounted a

six-inch gun whose rounds weighed more than 150 pounds each, and weighed 188

tons. Its road speed was given as 12.5 miles per hour—presumably downhill with

a tail wind. It took more than a year to complete two prototypes. To apply a

famous line from the classic board game PanzerBlitz, “The only natural enemies

of the Maus were small mammals that ate the eggs.”

The complete worthlessness of the Maus as a fighting vehicle

in the context of World War II needs no elaboration. Neither does the total

waste of material resources and engineering skill devoted to the project. The

Maus was nevertheless a signifier for Germany’s panzer force during the rest of

the war. Apart from its direct support by Hitler, the Maus opened the door to a

comprehensive emphasis on technical virtuosity for its own sake, in near-abstraction

from field requirements. The resulting increases in size at the expense of

mobility and reliability were secondary consequences, reflecting the

contemporary state of automotive, armor, and gun design. After 1943, German

technicians turned from engineering to alchemy, searching for a philosopher’s

stone that would bring a technical solution to the armored force’s operational

problems. Hubris, idealism—or another example of the mixture of both that

characterized so many aspects of the Third Reich’s final years?

The Maus thread, however, takes the story a few months ahead

of itself. Its antecedent combination of institutional infighting, production

imbroglios, and declining combat power led an increasing number of Hitler’s

military entourage to urge the appointment of a plenipotentiary

troubleshooter—specifically Heinz Guderian. Guderian describes meeting

privately on February 20, 1943, with a chastened Führer who regretted their

“numerous misunderstandings.” Guderian set his terms. Hitler temporized. He was

given the appointment of Inspector-General of Panzer Troops, reporting directly

to Hitler; with inspection rights over armored units in the Luftwaffe and the

Waffen SS, and control of organization, doctrine, training, and replacement.

That was a lot of power in the hands of one officer.

There was also a back story. Guderian had spent most of 1942

restoring his stress-shaken health, which centered on heart problems, and

looking for an estate suitable to his status, to be purchased with the cash

grant of a million and a quarter marks Hitler awarded him in the spring of

1942. Norman Goda establishes in scathing detail that once Guderian became a

landed gentleman on an estate stolen from its Polish owners, his reservations

about Hitler as supreme warlord significantly diminished. Cash payments, often

many times a salary and pension, were made to a broad spectrum of officers and

civilians in the Third Reich—birthdays were a typical justification. Since

August 1940, Guderian had been receiving, tax-free, 2,000 Reichsmarks a

month—as much as his regular salary. Similar lavish gifts were so widely made

to senior officers that Gerhard Weinberg cites simple bribery as a possible

factor in sustaining the army’s cohesion in the war’s final stages.

The image of an evil regime’s uniformed servants proclaiming

their “soldierly honor” while simultaneously being bought and paid for is so

compelling that attempting its nuancing invites charges of revisionism.

Nevertheless there were contexts. A kept woman is not compensated in the same

fashion as a streetwalker. Dotation, douceur, “golden parachute,” hush money,

conscience money, or bribe—direct financial rec ognitions of services rendered

the Reich were too common to be exactly a state secret. Guderian and his

military colleagues were more than sufficiently egoistic to rationalize the

cash as earned income, as recognition of achievement and sacrifice in the way

that milk and apples are necessary to the health of the pigs in George Orwell’s

Animal Farm.

The appointment Hitler signed on February 28, 1943,

ostensibly gave Guderian what he requested. But lest any doubt might remain as

to who was in charge, only the heavy assault guns, still in development stages,

came under Guderian’s command. The rest, whose importance was increasing by the

week, remained with the artillery. It was a relatively small thing. But

Guderian’s complaint that “somebody” played a “trick” on him belies his own

shrewd intelligence and low cunning. The desirability of trust between the head

of state and the general in such a central position was overshadowed in

Hitler’s mind by Lenin’s question: “Kto, kogo?” (Who, whom?): the question of

who was to be master. Guderian had spent a year in the wilderness. Now he was

back on top. Omitting the assault guns was a reminder that what had been given

could be withdrawn at a chieftain’s whim. It might well make even a principled

man think twice before deciding and thrice before speaking. And Hitler’s army

was increasingly commanded by pragmatists.

From the Führer’s perspective, Guderian’s appointment was

one of the heaviest blows he had struck against the High Command. The ground

forces’ key element, the panzers, were now under his personal authority—at one

remove, to be sure, but Guderian was the kind of person whose ego and energy

would focus him on the job at hand, and whose temperament was certain to lead

to the same kinds of personal and jurisdictional clashes that had characterized

his early career. Hitler would have all the opportunities he needed either to

muddy the waters or to resolve controversies, as circumstances indicated.

Albert Speer’s appointment as Minister of Armaments in

February 1942 brought no immediate, revolutionary change to Germany’s war

industry. But Speer had Hitler’s confidence, as much as anyone could ever

possess it. He was an optimist at a time when that was a declining quality at

high Reich levels. He concentrated on short-term fixes: rationalizing

administration, improving use of material, addressing immediate crises. And he

faced a major one in tank production.

In September 1942 Hitler called for the manufacture of 800

tanks, 600 assault guns, and 600 self-propelled guns a month by the spring of

1944. In April 1944 the army’s panzer divisions had fewer than 1,700 of their

total authorized strength of 4,600 main battle tanks: Panthers and Panzer IVs.

That gap could not be bridged by admonitions to take better care of equipment

and report losses more accurately. The long obsolete Panzer II was upgraded

into a state-of-the-art tracked reconnaissance vehicle. But a glamorous

renaming as Luchs, or Lynx, could not camouflage an operational value so

limited that production was canceled after the first hundred. Other resources

were also diverted to the development of a family of tracked and half-tracked

logistics vehicles and increased numbers of armored recovery vehicles, both in

their own ways necessary under Russian conditions. The growing effectiveness of

the Soviet air force led to the conversion or rebuilding of an increasing

number of chassis into antiaircraft tanks with small- caliber armaments. The

continued manufacture of early designs—again necessary to maintain even limited

frontline strength—further impeded production. Between May and December 1942,

tank production actually declined despite constant encouragement and repeated

threats from the Reich’s highest quarters.

One positive result of the slowdown was the ability to

address the Panther’s shortcomings. The original Model D received improved

track and wheel systems. Das Reich received a battalion of them in August, 23rd

Panzer Division in October, and 16th Panzer in December. All played crucial

roles in Army Group South’s fight for survival. The D’s successor, the Model A,

had a new turret with quicker rotation time and a commander’s cupola. Both were

important in the target-rich but high-risk environment of the Eastern Front.

Engine reliability remained a problem, in part because of quality control

difficulties in the homeland, and in part defined by the tank’s low

power-to-weight ratio. Improvements to the transmission and gear systems

nevertheless reduced the number of engine breakdowns. Modifications to the

cooling system cut back on the number of engine fires.

Soft ground, deep mud, and heavy snow continued to put a

premium on driving skill. One Panther battalion reported having to blow up 28

tanks it was unable to evacuate. Fifty-six more were in various stages of

repair. Eleven remained operational. But during the same period Leibstandarte’s

Panther battalion reported only seven combat losses—all from hits to the sides

and rear. Of the 54 mechanical breakdowns, almost half could be ready within a

week. On the whole the improved Panther was regarded as excellent: consistently

able to hit, survive hits, and bring its crews back.

Toward the end of 1943 the High Command began rotating

battalions officially equipped with Panzer IIIs—the old workhorse was still

pulling its load—back to Germany for retraining on Panther Model As. The

reorganized battalions were impressive on paper: 4 companies each of 22 or 17

tanks, plus 8 more in battalion headquarters. First Panzer Division welcomed

its new vehicles in November. Others followed, army and SS, the order depending

on which division could best spare a battalion cadre. By the end of January 1944

about 900 Panther As had reached the Russian front, in complete battalions or

as individual replacements.

As good as they were, the Panthers were a drop in the bucket

compared to the mass of Soviet armor facing them. As compensation the High

Command began considering a Panther II. Beginning as an up-armored Model D,

during 1943 the concept metamorphosed—or better said, metastasized—into a

lighter version of the Tiger. Weighing in at over 50 tons, it was originally

scheduled to enter service in September 1943, but was put on permanent hold in

favor of its less impressive, more reliable forebear.

The same might have been better applied to another armored

mammoth. The Panzer VIB, the “King Tiger” or “Royal Tiger,” could trace its

conceptual roots all the way to the spring of 1941. Prototypes emerged in 1943;

the first production models appeared in January 1944. The VIB was best

distinguished by a redesigned turret with a rounded front and a cupola for the

commander. Its second characteristic feature was an 88mm L/71 gun (that

translates as 19 feet long!) that could take out any allied tank at extreme

ranges. Its frontal armor, more than seven inches in places, was never

confirmed as having been penetrated by any tank or antitank gun. Its Maybach

700 horsepower engine gave it a reasonable road speed of 24 miles per hour. But

if the King was dipped in the River Styx for strength, it was also left with an

Achilles heel. Its weight was immobilizing. Only major road bridges could

support it. The tonnage increased fuel consumption when fuel supplies were a

growing problem, and also overstrained the drive system to a point where

breakdowns were the norm.

The point was initially moot, since only five VIBs were in

service by March 1944. But the situation was replicated in other end-of-the-war

designs. The Jagdtiger was a tank destroyer version of the VIB carrying a 128mm

gun—not only the heaviest weapon mounted on a German AFV, but an excellent

design in its own right. At over 70 tons, however, and with only 20 degrees traverse

for its main armament, the vehicle was only dangerous to anything unfortunate

enough to pass directly in front of it.

The Panther’s tank destroyer spin-off was far more

promising. Indeed the Jagdpanther is widely and legitimately considered the

best vehicle of its kind during World War II. An 88mm L/71 gun, well-sloped

armor, and solid cross-country capacity on a 45-ton chassis made the

Jagdpanther a dominant chess piece wherever it appeared. Predictably,

preproduction difficulties and declining production capacity kept its numbers

limited.

For all the print devoted to the Panthers, the Tigers, and

their variants, the backbone of the armored force through 1945 remained the

Panzer IV. Its final versions had little enough in common with the “cigar

butts” of 1940. The Model H officially became the main production version in

March 1942. Its armor protection included side panels and grew to a maximum of

3.2 inches in front, at the price of increased weight (25 tons) that cut the

road speed to a bit over 20 miles per hour. A later J version incorporated such

minor modifications as wider tracks and wire-mesh side skirts just as effective

as armor plate in deflecting infantry-fired antitank rockets.

Guderian in particular considered the new version of a

well-tried system a practical response to the chronic frontline shortfalls in

tank strength in the East. The Panzer IV was relatively easy to maintain -and

relatively easy to evacuate when damaged. Over 3,000 of them would be produced

in 1943, and standard equipment of the army panzer divisions was set at a

battalion each of Panthers and Panzer IVs.

Guderian’s opposition to the assault gun had eroded with

experience. Not only was its frontline utility indisputable, it could be

manufactured faster and in larger numbers by less experienced enterprises than

the more complex turreted tanks. Guderian correspondingly advocated restoring

the panzer regiments’ third battalions and giving them assault guns as a working

compromise.

The vehicles he intended were significantly different from

the original assault guns and their underlying concept. The mission of

supporting infantry attacks had become secondary at best. What was now vital

was holding off Soviet armor. The self-propelled Marders, with their light

armor and open tops, were well into the zone of dangerous obsolescence. In 1943

the Weapons Office ordered the development of a smaller vehicle mounting a

scaled-down 75mm gun on the chassis of the old reliable 38(t). The 16-ton

Hetzer (Baiter) was useful and economical, and continues to delight armor buffs

and modelers. It was, however, intended for the infantry’s antitank battalions,

and did not appear in combat until 1944—one more example of diffused effort that

characterized the Reich’s war effort.

On the other hand, the Sturmgeschütz IIIG, with its 75mm

L/48 gun, seemed highly suited to tank destruction and was readily

available—until Allied bombing intervened. The factory manufacturing the bulk

of IIIGs was heavily damaged in late 1943. To compensate, Hitler ordered the

available hulls to be fitted to Panzer IV chassis. The result proved practical

enough to encourage the production of over 1700 Jagdpanzer IVs by November

1944, despite Guderian’s protest at the corresponding fallout of turreted

tanks. The new name of “tank destroyer” suited the vehicles’ new purpose,

though their predecessors continued in service under the original title,

creating confusion during and after the war that remains exacerbated by the

vehicles’ close resemblance.

The Jagdpanzer IVs were intended for the panzer divisions

and the assault gun battalions, whose number grew to over three dozen during

1943. A slightly heavier version with a 75mm L/70 gun like the Panther’s and

the unflattering nickname of “Guderian’s Duck” began entering service in August

1944. It proved first-rate against armor in Russia and the West; almost a

thousand were produced during the war. The “Duck’s” long gun made it

uncomfortably nose-heavy (the source of its sobriquet), but by then that was

among the least of the panzers’ problems.

Apart from a few emergency variations churned out in the

war’s final months, the technical lineup of Hitler’s panzers was complete. As a

footnote the design staffs, after years of work, finally developed the war’s

best armored car. The SdKfz 234/2 Puma had it all: high speed, a low

silhouette, and a 50mm L39 still effective against tanks in an emergency.

Unfortunately, by the time the Puma and its variants entered production, the

panzers’ need for a long-range reconnaissance vehicle was itself long past. Now

their enemies all too often found them.