‘I had been going ahead partly submerged, with about five

feet of my periscope showing. Almost immediately I caught sight of the first

cruiser and two others. I submerged completely and laid my course so as to

bring up in the centre of the trio, which held a sort of triangular formation.

I could see their grey-black sides riding high over the water. When I first

sighted them they were near enough for torpedo work, but I wanted to make my

aim sure, so I went down and in on them. I had taken the position of the three

ships before submerging, and I succeeded in getting another flash through my

periscope before I began action. I soon reached what I regarded as a good

shooting point.

Then I loosed one of my torpedoes at the middle ship. I was

then about twelve feet under water, and got the shot off in good shape, my men

handling the boat as if she had been a skiff. I climbed to the surface to get a

sight through my tube of the effect, and discovered that the shot had gone

straight and true, striking the ship, which I later learned was the Aboukir,

under one of her magazines, which in exploding helped the torpedo’s work of

destruction. There was a fountain of water, a burst of smoke, a flash of fire,

and part of the cruiser rose in the air. Then I heard a roar and felt

reverberations sent through the water by the detonation. She had been broken apart

and sank in a few minutes. The Aboukir had been stricken in a vital spot and by

an unseen force; that made the blow all the greater.

Her crew were brave, and even with death staring them in the

face kept to their posts, ready to handle their useless guns, for I submerged

at once. But I had stayed on top long enough to see the other cruisers, which I

learned were the Cressy and the Hogue, turn and steam full speed to their dying

sister, whose plight they could not understand, unless it had been due to an

accident. The ships came on a mission of inquiry and rescue, for many of the

Aboukir’s crew were now in the water, the order having been given, “Each man

for himself.” But soon the other two English cruisers learned what had brought

about the destruction so suddenly.

As I reached my torpedo depth, I sent a second charge at the

nearest of the oncoming vessels, which was the Hogue. The English were playing

my game, for I had scarcely to move out of my position, which was a great aid,

since it helped to keep me from detection. On board my little boat the spirit

of the German Navy was to be seen in its best form. With enthusiasm every man

held himself in check and gave attention to the work in hand.

The attack on the Hogue went true. But this time I did not

have the advantageous aid of having the torpedo detonate under the magazine, so

for twenty minutes the Hogue lay wounded and helpless on the surface before she

heaved, half turned over and sank. But this time, the third cruiser knew of

course that the enemy was upon her and she sought as best she could to defend

herself. She loosed her torpedo defence batteries on boats, starboard and port,

and stood her ground as if more anxious to help the many sailors who were in

the water than to save herself. In common with the method of defending herself

against a submarine attack, she steamed in a zigzag course, and this made it

necessary for me to hold my torpedoes until I could lay a true course for them,

which also made it necessary for me to get nearer to the Cressy.

I had come to the surface for a view and saw how wildly the

fire was being sent from the ship. Small wonder that was when they did not know

where to shoot, although one shot went unpleasantly near us. When I got within

suitable range, I sent away my third attack. This time I sent a second torpedo

after the first to make the strike doubly certain. My crew were aiming like

sharpshooters and both torpedoes went to their bullseye. My luck was with me

again, for the enemy was made useless and at once began sinking by her head.

Then she careened far over, but all the while her men stayed at the guns

looking for their invisible foe. They were brave and true to their country’s sea

traditions. Then she eventually suffered a boiler explosion and completely

turned turtle. With her keel uppermost she floated until the air got out from

under her and then she sank with a loud sound, as if from a creature in pain.

The whole affair had taken less than one hour from the time

of shooting off the first torpedo until the Cressy went to the bottom. Not one

of the three had been able to use any of its big guns. I knew the wireless of

the three cruisers had been calling for aid. I was still quite able to defend

myself, but I knew that news of the disaster would call many English submarines

and torpedo boat destroyers, so, having done my appointed work, I set my course

for home. . ..

I reached the home port on the afternoon of the 23rd, and on

the 24th went to Wilhelmshaven, to find that news of my effort had become

public. My wife, dry eyed when I went away, met me with tears. Then I learned

that my little vessel and her brave crew had won the plaudit of the Kaiser, who

conferred upon each of my co-workers the Iron Cross of the second class and

upon me the Iron Cross of the first and second classes.’

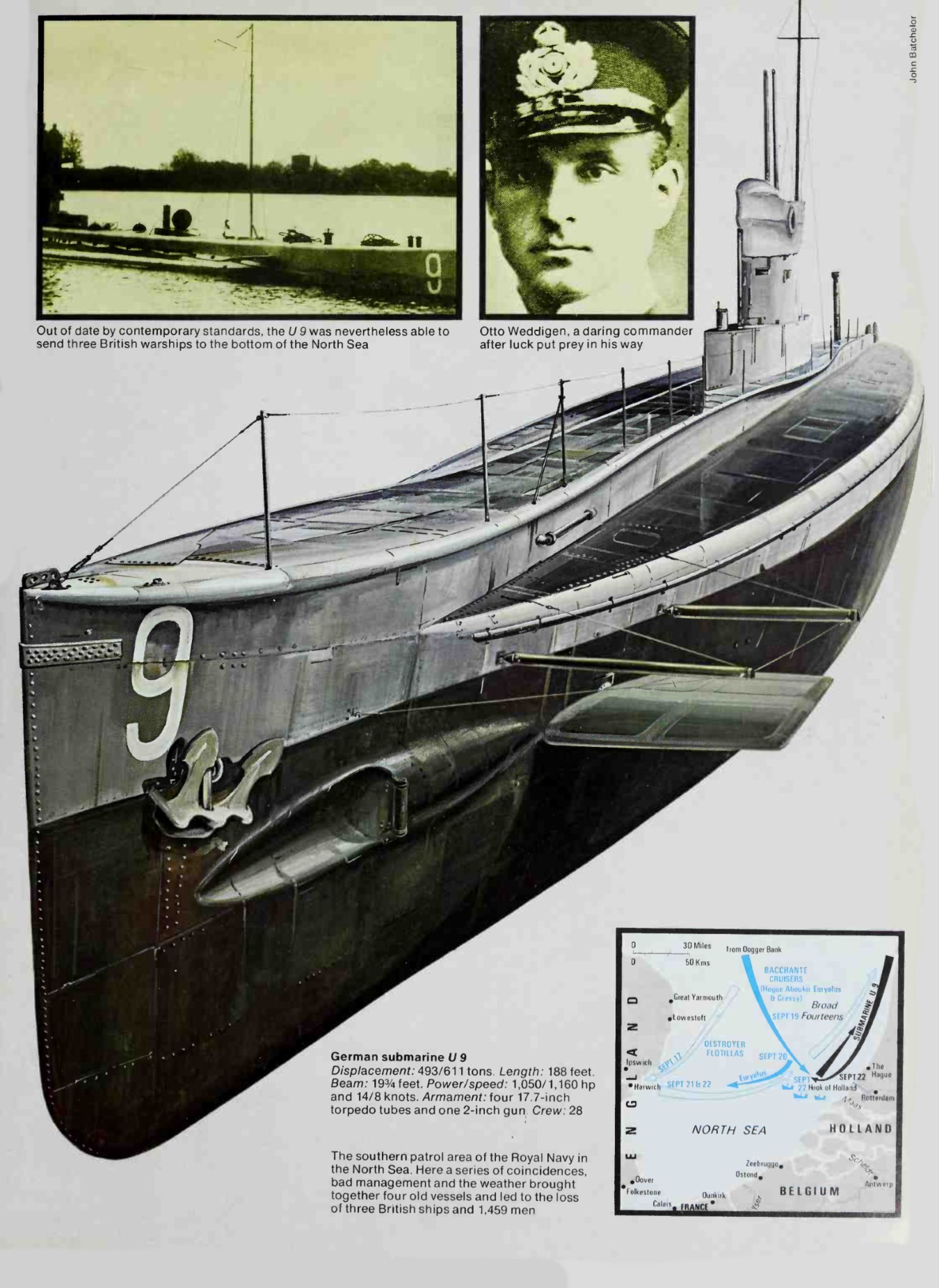

German Lieutenant Otto Weddigen, recalling his part in

the sinking of the Aboukir, Cressy, and Hogue by U-9 in September 1914, cited

in Source Records of the Great War, vol. 2, pp. 297–300.

The opening gambits of the war in 1914 did provide Germany

with some spectacular U-boat successes. Significantly, and quite unexpectedly,

these were not against unarmed merchantmen, but against powerful surface warships

that conventional wisdom claimed were immune from underwater attack. On 5

September 1914 Kapitanleutnant Otto Hersing’s U-21 made history by launching

the first submerged torpedo attack of the war, sinking the British light

cruiser HMS Pathfinder near Scotland’s Firth of Forth; on 22 September 1914

Kapitanleutnant Otto Weddigen’s U-9 created the first piece of enduring combat

iconography by destroying three of the Royal Navy’s 12,200-ton Cressy-class

cruisers in a single hour: HMS Cressy, Aboukir, and Hogue. In doing so,

Weddigen vindicated the submarine as an offensive weapon and provided his

country with a naval hero when it sorely needed one. Every aspect of the attack

was a new venture and would be described in surprisingly accurate detail in

postwar literature.

Surfacing that morning near the Maas Lightvessel after

having ridden out the previous day’s storm submerged, Weddigen and his crew

found calmer weather and clearer visibility. Captain, engineer, and the

watch-officer Johannes Spieß (who also would become a famous

skipper) were taking in the morning air after a fetid night and were bracing

themselves against the heavy swell. It was 0545, just before sunrise. As the U-boat

began charging her batteries with her notoriously smoky gasoline engines, Spieß

cursed the billowing exhaust that could betray her presence. Weddigen reduced

speed in order to cut down the smoke and went below, leaving Spieß

to carry out a lazy zigzag course along the Dutch coast, some twenty miles from

the town of Scheveningen. The crew were anxious to catch their first glimpse of

the enemy; anxious, too, to avenge the loss of their “chummy ship” U-15,

which had been rammed and sunk by the cruiser HMS Birmingham in August. Thus

when the first target hove into sight over the horizon, Spieß

all-too-readily identified it as one of the “Birmingham-class.” That

meant a light cruiser, U-9’s crew went swiftly to battle-stations. A series of

automatic commands triggered well drilled responses: battening hatches,

flooding tanks, switching from petroleum engines to batteries, arming

torpedoes. And in all this controlled swirl of activity, the last navigational

fix and target bearing were taken to begin setting up the first outlines of the

tactical picture. Poised at periscope depth despite the swell that could thrust

her exposed hull to the surface, U-9 waited for the target to approach. It soon

became clear that not one cruiser, but three were heading their way, steaming

in line ahead. No U-boat had ever faced such a threat before, and only one had

ever fired a torpedo in hopes of killing such Goliaths. So new was both the

situation and the technology that no one really knew for certain what would

happen when the fight began. Would U-9 survive against such massive surface

power? And if she could get in close enough for a kill, would the explosion of

her torpedoes against the cruisers’ hulls destroy her as well? These questions

were by no means idle. The officers all knew the fate of U-15 and they knew

that U-21 had been severely shaken by the explosion when torpedoing HMS

Pathfinder from a range of 1200 meters. It was generally accepted that at a

virtually lethal range of 500 meters they could expect heavy bow damage and the

possible destruction of her diving planes. In a series of short, snappy

periscope sights, Weddigen coolly calculated his chances and decided to strike

the cruiser steaming in the middle of the column. Weddigen cautioned the crew

to take the boat down to fifteen meters and stay there once he had fired, for

the range was “rather tight.” It was, in fact, just under 500 meters.

As Spieß later recalled, these were nerve-tingling moments. At

0720 Weddigen fired the first shot. Thirty-one seconds later a dull blow

announced the detonation and triggered jubilation in the U-boat. Unable to see,

they could only guess what was happening by listening to the abrasive

underwater sounds of cracking and wrenching soon emanating from her victim’s

death-agony. After a cautious wait, Weddigen brought u-g to periscope depth to

watch Aboukir sink. Meanwhile all available crew of U-9 were kept running

between bow and stern in order to maintain diving trim in the swell. The bow

had immediately become buoyant once the torpedo had fired and would only regain

its displacement as the bow tube was reloaded. A quick look from close range

revealed a serious miscalculation: the targets were not light cruisers at all,

but huge Cressys. By this time U-9 was committed. At 0755, thirty-five minutes

after his first shot, Weddigen made two direct hits on Hague from 300 meters.

But despite all efforts to tighten her turning-circle in the escape maneuver

racing full speed ahead on one screw and full speed astern on the other, U-9

scraped her periscope along Hogues’s hull. There was just time to reload when

HMS Cressy loomed into range. At 0820, precisely one hour after the first shot,

Weddigen fired his two stern torpedoes and struck from a range of 1000 meters.

Cressy died slowly, and Weddigen fired his last torpedo into her as a coup de

grace. Spieß’s

final periscope glimpse of the scene was especially vivid. Up until now U-9 had

been witnessing the destruction of machines and had not yet seen men die:

“But now life entered this tragic theater. The giant with his four stacks

rolled slowly but inexorably over onto his port side, and like ants we saw

black swarms of people scrambling first onto one side and then onto its huge

flat keel until they disappeared in the waves. A sad sight for a seaman. Our

task was now done, and we had to see to getting ourselves home as quickly as

possible … When we blew tanks and surfaced at 0850 there was no enemy to be

seen. The sea had closed over the three cruisers.” For many years to come,

veterans would hallow 22 September as “Weddigen Day,” and heroic

tales would capture much of the flavour of wartime reality, U-9’s successful

triple attack had been unprecedented, and many national presses – including those

of Allied powers – recognized the fact. The Kaiser cabled congratulations and

awarded Weddigen and his crew the Iron Cross; “bundles of congratulatory

telegrams,” one of the officers later wrote, awaited the submarine on

arrival home. The crew allegedly required a special shed to keep all the gifts

and letters that a grateful German public showered upon them. Admiral Scheer

explained the national euphoria thus: “Weddigen’s name was on everyone’s

lips, and especially for the navy his deed was sheer relief from the feeling of

having as yet achieved so little in comparison with the heroic deeds of the

army. Such a success was necessary in order to appreciate the value of the

submarine for our conduct of war.”

Yet once the euphoria had died down, many voices began to

minimize the success. The three cruisers, as the British press had correctly

pointed out, had been old and should never have been deployed in the exposed

area that had been Weddigen’s patrol zone. Indeed, as a British submariner

would observe in 1930, Weddigen’s success had been in large part due to

Britain’s “early policy of heroic but useless sacrifice.” Moreover, the

Royal Navy’s standing orders had actually required the warships to stop to pick

up survivors after the initial hit. This effectively turned the remaining two

warships into stationary targets for the likes of Weddigen. But on 15 October

1914 Weddigen’s U-9 again vindicated the U-boat when it torpedoed and sank the

modern 7,800-ton cruiser HMS Hawke northeast of Aberdeen. The U-boat’s mission

had covered over 1700 nautical miles and had expended virtually all her fuel.

It now seemed abundantly clear that submarine technology was allowing German

sailors to operate deep within British waters and to destroy heavily armed

ships. Weddigen this time won the coveted Prussian award Pour le merite.

U-Weddigen had become the stuff of legends. They persisted

long after his death in action in 1915, “an event which was felt most

painfully by the whole nation,” as his former watch-officer recalled in

1930. Myths conveniently ignored the fact that when attacking a British ship of

the line on 18 March 1915 in his new boat, U-29, he had been ignominiously

destroyed by an ancient maritime weapon – the ram. Ironically, the fatal blow

had been struck by the bow of the obsolescent battleship HMS Dreadnought.

Weddigen’s exploits had nevertheless encouraged public and naval leadership

alike. Widely disseminated throughout the country, a volatile mix of fact and

fiction about submarine adventures encouraged boldness in both naval and civil

circles.