June 1944 to May 1945

Doenitz sent out another nine U-boats to remote areas at the

end of May 1944, and the last U-tanker, U-490, was sent out from Germany in

support. By mid-May, U-490 was in the Northern Transit area. Apart from these

boats there were only five U-boats in remote theatres (excluding the Indian

Ocean) tying down Allied forces, and on 4 June one of these, U-505, was

captured by the Guadalcanal carrier group off Dakar. The code books were

recovered intact, but there was little to be gained from them at this late

stage of the war. Indeed, the US ‘10th Fleet’ discovered that the codebooks and

other documents on board U-505 were less up-to-date than their own records,

since the U-boat had been at sea for some months. Much more useful, however,

was the capture of the short-signals books.

On 1 June, Doenitz reviewed the U-boat war in the U-boat

Command diary. ‘Our efforts to tie down enemy forces have so far been

successful,’ he wrote. ‘The numbers of enemy aircraft and escort vessels,

U-boat killer groups and aircraft carriers allotted to anti-U-boat forces, far

from decreasing, has increased. For the submariners themselves the task of

carrying on the fight solely for the purpose of tying down enemy forces is a

particularly hard one.’

At this time Doenitz and all members the armed forces were

mostly concerned with the impending Allied invasion of Normandy, with large

numbers of U-boats lying in bomb-proof pens along the French and Norwegian

coasts with a view to impeding the invasion of either country. The ‘electric’

U-boats had been held up by Allied bombing and were not expected to enter

service until January 1945 (in fact, the first long-range ‘electric’ U-boat did

not commence operations until the last days of the war).

However, there was some hope with the advent of the

schnorkel. This originally Dutch invention was essentially an air mast raised

to the surface of the sea that enabled a submerged U-boat to run its diesel

engines and thereby recharge its batteries without having to come to the

surface. The invention was, of course, a major advantage at a time when

aircraft were sinking so many surfaced U-boats, and the Germans claimed to have

invented it independently of the Dutch. The schnorkel was by no means a

cure-all as it emitted a stream of gases in operation that could be seen a long

way off, so schnorkelling was conducted at night. Even so, the head of the schnorkel

could be detected by the new 3cm radar entering into Allied service. However,

the improved Naxos-U radar search receiver could pick up these radar

transmissions, enabling the U-boat to submerge again almost instantly. Use of

the schnorkel reduced the U-boats’ speed to about 5 knots, whereas on the

surface they had been accustomed to making 17 knots. Even a slow convoy would

leave a schnorkelling U-boat behind, but the new device proved to be so useful

as a defensive measure that on 1 June, Doenitz ordered that no U-boat should

proceed on operations without one.

The schnorkel was ideally suited to milk cows, which had no

interest in chasing convoys but only wanted to preserve themselves from air

attack. But the development was too late for the U-tankers. On 1 June, the last

survivor, U-490, was already at sea, cruising through the North Atlantic air

gap on a southerly heading. The U-boat Command war diary lists U-490 as one of

several boats recalled that day to France for fitting with a schnorkel.

Presumably this was a typing error in the diary, for U-490 already possessed

the equipment and made no effort to return to France. On the 7th, U-boat

Command ordered U-490 to continue southwards as planned.

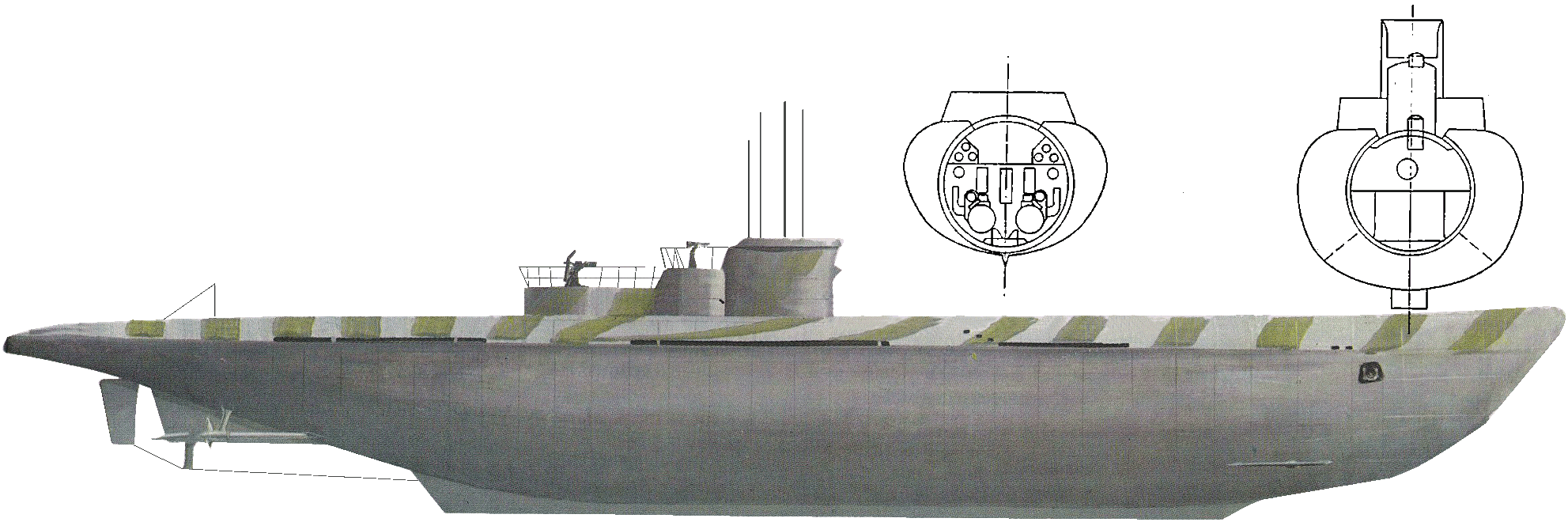

U490 was commanded by the experienced Oberleumant zS Gerlach,

and had left Kiel on 4 May with instructions to proceed to the mid-Atlantic

where she was to support operations for the remote theatres, before heading on

into the Indian Ocean to assist the return of the U-boats remaining there. The

39-year-old Gerlach was another sailor promoted from the lower deck, having

served on the successful U-124 between July 1940 and September 1941. He had

then been selected for officer training, after which he had returned to U-124

as a watch officer in 1942 before being sent on the commanders’ course in

1942-3. He had commissioned U-490 on 27 March 1943 and the boat had remained in

the Baltic for correction of bombing damage and subsequent serious flooding,

and for training until her services were required.

U490 successfully negotiated the difficult Northern Transit

area as she passed from the North Sea into the North Atlantic, and reported a

convoy on 4 June. Meanwhile, the crew had difficulty with her schnorkel, which

appeared to be usable only in fairly calm seas. U-490 was located by H/F D/F in

the middle of the ocean as she made a weather report on the 10th. Gerlach,

described by his crew as nervous about Allied air activity, wanted to maintain

radio silence, but he could not ignore a direct order requiring him to transmit

information about the weather as he passed through the Atlantic. The American

escort carriers were at this time making a concerted drive against the handful

of U-boats stationed in the Atlantic to provide weather reports. On 11 June, U-490

made another weather transmission, but it was to be her last. She was caught on

the surface within hours by aircraft from the Croatan carrier group, but

managed to submerge and went very deep.

She was then hunted all through the night and the next day

by the carrier’s destroyer escorts, which dropped 189 depth-charges in all. U-490

carried some experimental guinea pigs aboard. These kept squealing during the

attacks and had to be destroyed to reduce the noise. Eventually her air ran out

and she was forced to return to the surface. The destroyers in the meantime had

played the trick of moving off in opposite directions at decreasing speed

(giving the sound effect of a high-speed departure), and then creeping slowly

back to the target area. The U-tanker surfaced and when it was at once attacked

with heavy gunfire, Gerlach ordered his boat to be scuttled; all sixty crew

members were rescued. American interrogators described the crew as

‘undistinguished’, but remarked on the unusual seniority of the petty officers.

The crew volunteered to answer ‘honourable questions’ provided they were not

handed over to the British, but they had little new to report.

As U490 had not refuelled a single U-boat when she was sunk,

this effectively wrecked the last of Doenitz’s hopes for overseas operations,

and only one or two U-boats were able to patrol in remote waters, with

occasional refuelling by fuel sharing with one another. The war diary of U-boat

Command shows that just three U-boats were successfully refuelled by other

attack U-boats in the period June 1944 to May 1945.

However, the loss of U-490 was not immediately appreciated

as her crew had been too agitated to remember to send a final distress signal.

As late as 27 June, U-boat Command ordered U-490 to make for Penang at high

speed, where the boat was to load up with essential war supplies, with a

minimum docking time, and return home. While on passage (in either direction),

any Type IXC boats in the Indian Ocean (presumed to be U-183, U-510, U-532 and

U-843) were to be refuelled for the journey home.

The Type XB minelayer U-233 had been commissioned on 22

September 1943 by the 36-year-old Kapitaenleumant Steen, who had previously

been the First Officer on her sister ship, U-117, from October 1941 to February

1943, and had subsequently attended a commanding officers’ course. Most of the

crew were new recruits. After the usual working-up exercises in the Baltic,

which involved a practice minelaying mission of 132 mines in that sea during

the winter of 1943, U-233 received a full overhaul and refitting from February

1944. She left Kiel on 27 May for her first war patrol, with orders to lay

sixty-six mines apparently off Halifax, Canada. However the U-boat Command war

diary claims that U-233 received ‘alternative orders’ on 17 June to carry out

her minelaying operation off Halifax. She was not fitted with a schnorkel and,

according to her crew when later interrogated, there had been no plans to

deploy U-233 for refuelling purposes after the minelaying operation, neither

did the boat carry spare parts for other U-boats.

Travelling on the surface at night to recharge her

batteries, U-233 entered the Northern Transit area, which was then the scene of

a massive search by Coastal Command for outward-bound U-boats, but she was one

of the few fortunate boats to break through, albeit after many tribulations. On

1 June, U-233 sighted many aircraft and next day was suddenly attacked by a

four-engined bomber, too late to dive. U-233 defended herself with her 37mm and

two 20mm cannons scoring some hits, but the aircraft still managed to drop five

bombs that exploded all around the U-boat, remarkably causing no damage. The

U-minelayer seized the chance to dive.

After resurfacing, U-233 was again forced to dive by

aircraft combing her likely route and changed course in a successful effort to

shake off her aerial pursuers. Steen then steered for the east coast of the

USA, surfacing at night just long enough to recharge his batteries. The

quick-firing 37mm flak gun had repeatedly jammed during the engagement with the

bomber and test-firing two weeks later caused a shell to explode in the barrel,

rendering it useless.

Then her luck ran out. Now close to Nova Scotia, Canada, she

sent a message by W/T. This was intercepted by H/F D/F, leading to a search by

the Card carrier group. The carrier aircraft spotted an oil slick on 2 July and

dropped sonobuoys, which gave a positive response to underwater sounds,

although thick fog interfered with further aerial operations. The US destroyer

escort finally gained passive sound contact (i.e. listening only, without using

active Asdic) on 5 July. This was not detected by the U-minelayer, which was

then floating at a depth of 30 to 50 metres while servicing her stern

torpedoes. Suddenly the horrified crew heard the whine of the propellers of the

destroyer Baker, followed by the shocking impact of depth-charges all around

the boat.

U-233 was badly shaken, the lights went out and the boat

plunged out of control to 120 metres. Water poured in through a leak in the

stern and a heavy aft torpedo was toppled out of its stay, killing a crew

member. When a second pattern of depth-charges drove U-233 to 230 metres, a

desperate Steen gave the order to ^low tanks’ and surface. The milk cow managed

to reach the surface, where she was instantly engaged with a hail of fire at a

range of only 500 metres. Two destroyer torpedoes also struck the hapless

U-minelayer, but had been fired from so close that they did not have time to

arm themselves and bounced off without exploding. Steen gave the order to

abandon ship, while the Chief Engineer went below to scuttle the U-boat.

Meanwhile, shells continued to land all around as the crew jumped overboard,

many losing their lives at this point.

Then another destroyer, the Thomas, stormed in and rammed

the luckless U-233 which subsequently sank. Steen himself was severely wounded,

but was supported in the sea by one of the surviving crew members. The American

destroyers rescued Steen and twenty-nine other survivors from the sixty-man

crew. It transpired that so accurate had been the American fire on the conning

tower as the U-boat crew tried to abandon ship that virtually all the rescued

survivors were those who had escaped from the forward hatch. Steen died of his

wounds the following day and was buried at sea from the deck of the carrier

Card. U-233 had been sunk before she could drop her mines and her loss was not

recognized by U-boat Command until 11 August. Interrogation of survivors

established that the crew were ‘dreadful’, almost devoid of experience, except

for Steen himself and a few petty officers added to leaven the mixture. Steen

had been well liked and the crew were unusually security conscious.

As a result of the early loss of the cows, the U-boats

engaged in the remote waters campaign (excluding the Indian Ocean) sank only

twenty ships between January and September, while thirteen of the U-boats

engaged in this campaign were themselves sunk.

The Allies invaded Europe on 6 June, and by August the

Biscay bases were in such danger of capture, and escort groups in the Bay posed

such a threat, that all the U-boats within their pens were despatched either to

Norway or, in the case of a few long-range boats, to the Indian Ocean. U-boat

Command had already warned boats at sea, on 12 June, that they should retain

enough fuel to reach Bergen, if necessary, rather than a French port. Some

other U-boats were in no fit state to be sent out to sea and had to be scuttled

in the French ports. Among them were: U-129, Type IXC, which we have

encountered frequently at fuelling rendezvous and which had returned safely

from her last aggressive patrol off Brazil; the U-cruiser U-178, returned from

Penang; and U-188, Type IXC/40, returned from the Indian Ocean after an

eventful journey. All were scuttled between 18 to 20 August. Kapitaenleumant

von Harpe of U-129 had performed an extraordinary job in keeping the boat

operating successfully during his tenure (July 1943 to July 1944) while so many

were being sunk around him. He would be rewarded with command of one of the

brand-new ‘electric’ U-boats, U-3519, in January 1945, but boat and commander

were lost off Warnemuende (Germany) in March 1945 after an air attack.

By 25 August, there remained no serviceable U-boats at

Bordeaux, and the boatless crews, dockyard workers, army troops and German

civilians reassembled at La Rochelle, from where 20,000 would attempt to make

the journey back across France to Germany. The unwanted ex-Italian UIT21 had

been one of those scuttled at Bordeaux on 25 August and her former crew, including

Wilhelm Kraus, now set out for Germany on bicycles. Many of them were captured

in mid-France by partisans and Kraus was not released until the end of 1946.

The general chaos, with U-boats attempting to redeploy to

Norway from France, resulted in complications for boats returning from remote

waters. The homeward-bound U-516 (Kapitaenleutnant Tillessen), low on fuel, was

unexpectedly required to steer for Norway instead of her closer French base.

She signalled her predicament on 16 August and was ordered to meet a U-boat

giving weather reports south-west of Iceland. On the 25th, U-858, the weather

boat, reported that she had refuelled U539 at the rendezvous (AK1832), but had

not seen U-516. U-855 was appointed as replacement weather boat while a fresh

rendezvous between U-855 and U-516 was fixed for the same area on 3 September.

Tillessen waited two days for U-855 at her rendezvous south of Iceland before

signalling to U-boat Command that the supply boat had failed to appear. The

Type VIIC boat U-245 was at once directed at full speed to her aid, but on the

9th U-516 was able to report that she had been refuelled by U-855 after all.

Both boats returned to Norway.

After her return from the North Atlantic in January 1944, U-219

(Korvet-tenkapitaen Burghagen) had been prepared for a special cruise, as the

first blockade runner of her class to the Far East. The minelayer was to be

fitted out with supplies, rather than mines (the mineshafts had a huge

capacity), but eight torpedoes would also be taken on board to retain some

offensive capability from her two stern torpedo tubes. Planning for the event

took three to four months, during which time radio equipment was loaded for

Japan (the port of Kobe), also substitute machine parts, torpedo parts, medical

supplies, operational orders, spare parts for the Arado-196 seaplane at Penang

(a parting gift, long before, from a German auxiliary cruiser), duraluminium,

mercury and optical items for the Japanese. However, contrary to recent

reports, there were no parts for a putative Japanese atomic bomb, nor any

foreign personnel aboard.

No one knew how the U-minelayer would behave with such a

loading, so the first test cruise of U-219 in April was, to say the least,

fraught with interest. Senior engineers from the 12th U-boat Flotilla went on

board to give what aid they could. During the first trim-dive U-219 sank like a

stone, but the engineers managed to recover her poise. After return to her

bunker, as much as possible was done to save weight, including the removal of

the large 105mm gun on deck and all its ammunition.

Schnorkel trials began on 1 May. When the Allied invasion

began, the bunkers suffered constant air attack but U-219 remained safe in

hers, although shortage of supplies caused a long delay in equipping the

U-minelayer, which was also fitted with one of the new high-pressure designs of

lavatory. This could expel its contents when at great depth, but required

careful operation – faulty manipulation was to cause the accidental flooding

and loss of one U-boat later in the war.

The two Type IXD1 U-transporters, U180 (Oberleutnant zS

Reisen) and U-195 (Oberleutnant zS Steinfeldt), were recommissioned at Bordeaux

as the other two blockade runners planned to sail to the Indian Ocean. Both had

needed replacement diesel engines to permit this trip and were to be joined by

U-219.

The former U-boat bases on the west coast of France were

declared by Hitler to be ‘fortresses’, to be fought to the last man, but this

meant that munitions had somehow to be ferried to them. U-boats were the

vessels of choice, two small attack boats had already carried out a ferry

operation, and U-180 and U-195 seemed to the Army to be especially good

candidates. They were loaded with dynamite and ammunition for a planned

operation to St Malo and Lorient, but the naval staff were singularly

unenthusiastic -not to mention the crews – and finally seized on the shortage

of supplies at Bordeaux as the excuse not to send the U-transporters out on

this mission.

U-219 finally left her bunker on 20 August. It took until

the 23rd to reach Le Verdon at the mouth of the River Gironde where she had to

wait for U-195 and U-180, which had also sailed on the 20th. (According to a

decrypted W/T message, U-219 had attempted to sail from Le Verdon on the 23rd,

but an air attack on the escort had caused a withdrawal.) As this valuable

assembly of blockade runners waited for a propitious moment to break into the

heavily patrolled Bay of Biscay, the crews saw the destroyers Z-24 and T-24

attacked by a cloud of some forty Mosquito fighter-bombers. Both ships would be

sunk by air attack at Le Verdon, respectively on the 25th and 24th. The signal

announcing the imminent departures of U-180, U-195 and U-219 was decrypted by

British Intelligence but, owing to a shortage of suitable escorts, U-219 did

not enter the Bay of Biscay until the 24th. Finally the U-boat group emerged in

the evening and put to sea with orders to sail to the Far East (Penang), with a

paltry escort of only two M-boats. Evidence of heavy Allied aerial activity

caused the boats to dive in only 50 metres of water, instead of the more common

200 metres.

It would have been at this time that U-180 disappeared

without trace. She is commonly supposed to have hit a mine and sank, the

sinking generally being listed as having occurred on 22 August, but this does

not fit the information given above, derived from decrypts and survivors of U-219.

Meanwhile, U-boat Command continued to give estimates other supposed position

until 3 October, when U-180 was presumed lost. The historian Alex Niestle has

discovered that the escort left U-180 in deep water late on 23 August, so that

a mine sinking is most unlikely. A more probable explanation for the loss, in

the view of the author, is a schnorkel defect (compare the troubles experienced

by U-219 at the same time, below). Experiences from other U-boats make it clear

that a sufficiently serious schnorkel failure could poleaxe an entire crew

within sixty seconds.

U-219 began to use her schnorkel on the 26th, despite her lack

of experience. The next few days were spent acquiring better knowledge of the

schnorkel as the boat headed west. By 2 September, U-219 had reached the

Atlantic, and surfaced briefly to clear the air in the boat and to determine

her position. Then she began schnorkelling again. But on the 15th the device

suddenly failed and could not be repaired, jammed at an angle of 45 degrees. U-219

ran thereafter on the surface at night for the minimum length of time needed to

recharge her batteries; otherwise she remained submerged Meanwhile, the

homeward-bound torpedo transport U-1062 required more fuel if she was to reach

Norway. U-1062 was returning from Penang with a cargo of rubber and other

strategic materials and had already had an eventful ride. But now she had been

diverted from her originally intended French base owing to the Allied advance

towards the Biscay ports. U-219 was conveniently close and U-boat Command

radioed orders on 21 September for her to supply U-1062 at sundown south-west

of the Cape Verde Islands, at a position of about 11.30N 34.30W.

But the rendezvous had already been revealed when the

exchange of signals between U-boat Command and U-1062 on the 18th had been

decoded, after the disguised grid reference had been cracked by local H/F D/F

indicating the location of U-1062. The Mission Bay and Tripoli carrier groups

were moved to the area and they mounted continuous air patrols looking for the

U-boats. Arriving at the rendezvous in good time on 28 September, U-219 was

alarmed to hear far-off explosions. She surfaced at dusk and the crew manned

the anti-aircraft guns. Unknown to her crew, the U-minelayer had been detected

by the large radar on the Mission Bay carrier.

Suddenly, in darkness, a carrier aircraft flew over at an

altitude of only 70 metres. It saw the cow too late, circled and attacked.

Heavy flak from the cow’s 20mm and 37mm guns shot the aircraft down, but not

before it had dropped several bombs which exploded all around the boat. As the

spray fell away, the stunned crew of U-219 found that their boat had stopped

dead in the water, although there appeared to be no serious damage. A second

aircraft saw the gunfire and closed, firing rockets that all missed. U-219

remained on the surface and was harried with guns and bombs before diving.

Burghagen debated what to do. He thought it prudent to abandon the rendezvous,

but U-boat Command ordered him to remain searching. All night the crew could

hear the sound of distant explosions, blissfully ignorant of the fact that U-219

had just been chased by a Fido that had failed to make contact, and was even

now being hunted with sonobuoys.

At light next day (the 29th), Burghagen sighted searching

destroyers but still continued to wait hopefully for U-1062. U-219 surfaced on

the 30th to recharge her batteries and then dived again to the constant thud of

distant bombs and depth-charges.

Meanwhile, U-1062 had been located by sonobuoys on 30

September, chased repeatedly and unsuccessfully with Fidos, and finally sunk by

hedgehog and depth-charge attacks by destroyers of the Mission Bay carrier

group while close to the rendezvous, south-west of the Cape Verde Islands.

There were no survivors.

On the first day of October another Allied search group was

heard at the rendezvous by U-219, looking for the cow whose presence was still

suspected. Next day the batteries were again depleted and U-boat Command had

made no further pronouncement (the reason for which is unknown. U-boat Command

did not recognize that U-1062 had been sunk until 2 December, by which time the

staff claimed to have had no word from U-219 either.) U-219 drifted underwater

at creeping speed for several days -so many that her crew became ill and it

became necessary on 4 October to surface again to vent the boat. She was

promptly located by an aircraft from the persistent Mission Bay group, but the

intended bombs fell short. Sonobuoys were deployed and another Fido was dropped

after a few hours. An explosion was heard but U-219 was unharmed.

On the following day, Asdic echoes came too close for

comfort and Burghagen finally abandoned the rendezvous, heading south. The

Tripoli carrier group did not, however, abandon the hunt for this valuable

U-minelayer. U-219 had crossed the equator by the 11th, submerged but with due

ceremony, and thereafter she ran mostly on the surface at night, albeit with

constant dives before radar alarms. Unknown to Burghagen, the Tripoli was still

in pursuit. On 30 October, aircraft from the Tripoli carrier group finally

relocated U-219 with sonobuoys off South Africa and attacked the sound location

with depth-charges. Underwater explosions were heard, but U-219 escaped (her

crew seems to have been oblivious to this attack).

U-219 finally reached her most southerly point on 11

November, having at last thrown off her tenacious pursuer. Here she had to

wrestle with some engine trouble before steering north-east, into the Indian

Ocean and towards Penang. U-boat Command altered the destination base to

Djakarta on the 20th, citing the new proximity of Allied bombers to Penang as

the reason for the change.

When masts were seen well into the Indian Ocean on 26

November, Burghagen made a submerged attack, firing two torpedoes. One

detonation was heard but, on coming to the surface, nothing could be seen of

the target. U-219 claimed a sinking on the basis of this flimsy evidence, but

in fact no merchant ship had been sunk; evidently Burghagen lacked confidence

in the claim too, since he did not repeat it to U-boat Command after arrival at

base.

U-219 at last reached the rendezvous for her Japanese escort

in the Sunda Strait, punctually on 12 December. She hung around nervously, all

crew on deck for fear of an attack by an Allied submarine in these infested

waters. Burghagen’s fears were not eased when the ‘escort’ proved to be a Japanese

fishing cutter that proceeded casually to Djakarta with the helpless

U-minelayer tagging slowly along behind. However, she reached port without

mishap.