TAMERLANE (1336–1405). Turkic chieftain and conqueror.

He was not Mongol, but sought to trace Mongol connections through his wife’s

ancestors. His English name is a corruption of the Persian Timür-i Leng, “lame

Timür.” Tamerlane is important not only for his conquests, but for his role in

definitively ending the Mongol era in Turkistanian history, and for his attack

on the Golden Horde in 1395–1396, which began with the Battle of the Terek

River, in which the army of Toqtamysh was decisively defeated, and ended with

the destruction of much of the sedentary base of the Golden Horde along the

lower Volga, including Sarai.

In 1401 the great Islamic historian Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406)

was in the city of Damascus, then under siege by the mighty Tamerlane. Eager to

meet the famous conqueror of the day, he was lowered from the walls in a basket

and received in Tamerlane’s camp. There he had a series of conversations with a

ruler he described (in his autobiography) as ‘one of the greatest and mightiest

of kings . . . addicted to debate and argument about what he knows and does not

know’. Ibn Khaldun may have seen in Tamerlane the saviour of the Arab–Muslim

civilization for whose survival he feared. But four years later Tamerlane died

on the road to China, whose conquest he had planned.

Tamerlane (sometimes Timur, or Timurlenk, ‘Timur the Lame’ –

hence his European name) was a phenomenon who became a legend. He was born,

probably in the 1330s, into a lesser clan of the Turkic-Mongol tribal

confederation the Chagatai, one of the four great divisions into which the

Mongol empire of Genghis (Chinggis) Khan had been split up at his death, in

1227. By 1370 he had made himself master of the Chagatai. Between 1380 and 1390

he embarked upon the conquest of Iran, Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), Armenia and

Georgia. In 1390 he invaded the Russian lands, returning a few years later to

wreck the capital of the Golden Horde, the Mongol regime in modern South

Russia. In 1398 he led a vast plundering raid into North India, crushing its

Muslim rulers and demolishing Delhi. Then in 1400 he returned to the Middle

East to capture Aleppo and Damascus (Ibn Khaldun escaped its massacre), before

defeating and capturing the Ottoman sultan Bayazet at the Battle of Ankara in

1402. It was only after that that he turned east on his final and abortive

campaign.

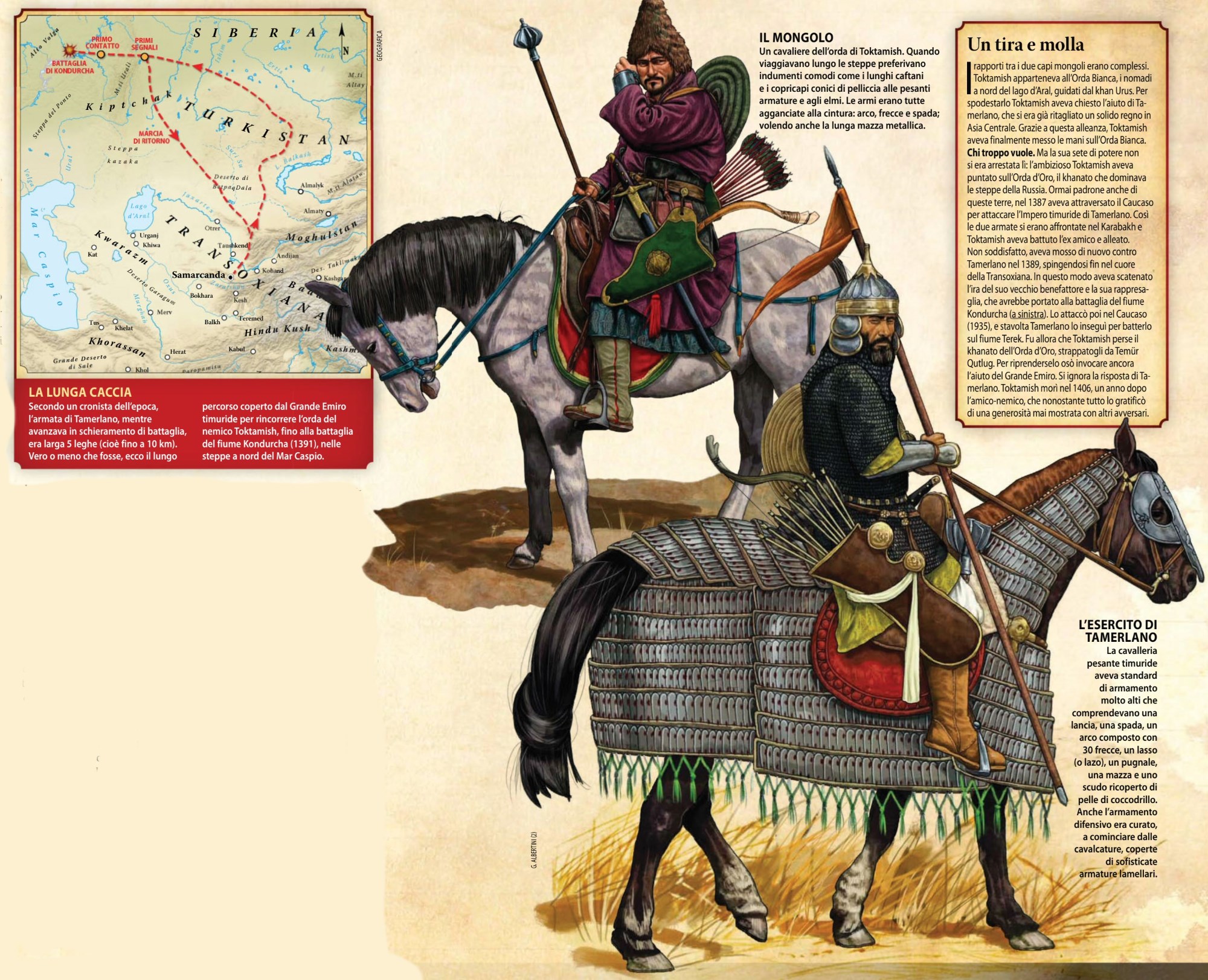

The Army

Tamerlane’s original army was a hodgepodge of leftover

Chaghatayid units: clans (Barulas, Jalayir, etc.), local soldiery created a

century earlier under the Mongol census (called qa’uchin, old units),

independent KESHIG (guards) tümens (nominally 10,000) that had outlived their

khan, and the Qara’unas, an old TAMMACHI garrison. Tamerlane did not disperse

these traditional units but controlled them by changing their leadership,

removing major cities such as Bukhara from their control, and eventually

recruiting new armies outside the Chaghatay Khanate, especially local units

from the defunct Mongol IL-KHANATE. Foreign troops and craftsmen-Indians,

Persians, Arabs both settled and bedouin, and Turks- were deported and settled

around Samarqand and Bukhara. By 1400 his own companions commanded about 13

tümens, while his sons commanded at least nine. Tamerlane ‘s sons’ tümens were

assembled from troops of all origins. The core of Tamerlane ‘s army was its

Inner Asian cavalry, but he also valued Tajik (Iranian) infantry units. In an

inscription he claims to have attacked Toqtamish in 1391 with 20 tümens, a

statement that at the usual 40 percent nominal strength is plausible.

Attack on the Golden Horde

The subjugation of Khorasan and Mazandaran, completed by

1384, led to the first of his expeditionary campaigns against western Iran and

the Caucasus in 1386-87.

Toqtamish’s father was a descendants of Toqa-Temür, one of

the “princes of the left hand,” or the BLUE HORDE, in modern

Kazakhstan, and his mother was of the QONGGIRAD clan from near KHORAZM. At the

time the Blue Horde was ruled by Urus Khan (d. 1377) and his sons, whose seat

was at Sighnaq (near modern Chiili). By allying with the Chaghatayid conqueror Tamerlane,

Toqtamish succeeded after many reverses in taking control of the Blue Horde (spring

1377). Later, local chronicles speak of Toqtamish as defending four tribes

(el)-Shirin, Baarin, Arghun, and Qipchaq-from the tyranny of Urus Khan. Once

enthroned in Sighnaq, Toqtamish led his four tribes west to defeat Emir Mamaq

(Mamay) of the Qiyat clan (1380) and reestablish GOLDEN HORDE rule over Russia

by sacking Moscow (1382).

Eventually, Toqtamish turned against his old patron, Tamerlane,

to pursue the Golden Horde’s old territorial claims in Azerbaijan (1385 and

1387), Khorazm, and the Syr Dar’ya region down to Bukhara (1388). Tamerlane

responded with a massive punitive expedition into Kazakhstan, which finally

cornered and defeated Toqtamish’s army near Orenburg (June 1391). Tamerlane

also wooed away Emir Edigü, leader of the Manghit (MANGGHUD) clan, from

Toqtamish’s camp. After rebuilding his power in the west, Toqtamish again

invaded Azerbaijan (1394); Tamerlane crushed his army again on the Terek (March

15, 1395) and sacked Saray and Astrakhan.

By now Tamerlane’s chief rival

was a one-time protegé, TOQTAMISH, ruler first of the BLUE HORDE and then of

the reunified GOLDEN HORDE in the northern steppe. First sacking Urganch

(1287), the capital of Toqtamish’s allied country, Khorazm, Timur launched a

“five-year campaign” (1392-96) against Baghdad’s Jalayir dynasty as

well as against western Iranian, Turkmen, and Georgian powers, culminating in

the sack of Toqtamish’s capital, New Saray, on the Volga and crippling

Toqtamish’s power.

Timur marched through the Darband Gates, a narrow pass

between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains. On 15th April 1395 the

armies of Timur and Toqtamish met near the river Terek, a strategic point where

so many battles had been fought. Timur himself took part until, as the

Zafarnama put it, ‘his arrows were all spent, his spear broken, but his sword

he still brandished’. This time Timur’s victory was complete.

Terek River, 22 April 1395

Abandoning his fortified camp on the banks of the Terek on

bearing of Tamerlane’s approach during a second campaign against him, Tokhtamysh

Khan shadowed the Timurid army until, on 14 April, they finally encamped facing

one another. On the 22nd Tamerlane arranged his forces for battle in 7

divisions, himself commanding the reserve of 27 binliks, and commenced his

attack under the cover of showers of arrows. Then, bearing of an advance

against his left wing, he led the reserve to its support and repelled the

attack but pursued the enemy too far so that, thus disorganised, be in turn was

repulsed and driven back. Disaster was averted by a mere 50 of his men who

dismounted, knelt on one knee and laid down a withering barrage of arrows to

bold back their pursuers while 3 Timurid officers and their men seized 3 of

Tokhtamysh’s wagons and drew them up as a barricade behind which Tamerlane

managed to rally his reserve. The advance guard of his left wing bad meanwhile

broken through between the attacking enemy divisions, while his son Mohammed

Sultan brought up strong reinforcements, positioning them on Tamerlane’s left

so that Tokhtamysb’s advancing right wing was finally forced to take flight.

The Timurid right wing having meanwhile been surrounded, its

commander ordered Ibis men to dismount and crouch behind their shields, under

the cover of which they were repeatedly attacked with lance and sword by

Tokhtamysb’s troops. They were finally rescued from these dire straits by the

division under Jibansha Behadur which, attacking from both flanks, obliged the

enemy left flank to fall back and then drove it from the field. Finally the

centres of both armies joined battle, Tokhtamysb’s giving way after a hard

fight, upon which the khan and his noyons quit the field. The Timurid pursuit

was close and bloody, most of those they captured being hanged.

Aftermath

The shattered remnants of Toqtamish’s army and of his

Russian vassals were pursued as far as Yelets, not far from the Principality of

Moscow. There Timur turned back not, as the terrified Muscovites believed,

because of the miraculous intervention of the Virgin Mary and still less

through fear of Moscow’s military might, but because he had no interest in

conquering the poor and backward Russian principalities.

Despite his reputation as a bloodthirsty tyrant, and the undoubted

savagery of his predatory conquests, Tamerlane was a transitional figure in

Eurasian history. His conquests were an echo of the great Mongol empire forged

by Genghis Khan and his sons. That empire had extended from modern Iran to

China, and as far north as Moscow. It had encouraged a remarkable movement of

people, trade and ideas around the waist of Eurasia, along the great grassy

corridor of steppe, and Mongol rule may have served as the catalyst for

commercial and intellectual change in an age of general economic expansion. The

Mongols even permitted the visits of West European emissaries hoping to build

an anti-Muslim alliance and win Christian converts. But by the early fourteenth

century the effort to preserve a grand imperial confederation had all but

collapsed. The internecine wars between the ‘Ilkhanate’ rulers in Iran, the

Golden Horde and the Chagatai, and the fall of the Yuan in China (by 1368),

marked the end of the Mongol experiment in Eurasian empire.

Tamerlane’s conquests were partly an effort to retrieve this

lost empire. But his methods were different. Much of his warfare seemed mainly

designed to wreck any rivals for control of the great trunk road of Eurasian

commerce, on whose profits his empire was built. Also, his power was pivoted

more on command of the ‘sown’ than on mastery of the steppe: his armies were

made up not just of mounted bowmen (the classic Mongol formula), but of

infantry, artillery, heavy cavalry and even an elephant corps. His system of

rule was a form of absolutism, in which the loyalty of his tribal followers was

balanced against the devotion of his urban and agrarian subjects. Tamerlane

claimed also to be the ‘Shadow of God’ (among his many titles), wreaking

vengeance upon the betrayers and backsliders of the Islamic faith. Into his

chosen imperial capital at Samarkand, close to his birthplace, he poured the

booty of his conquests, and there he fashioned the architectural monuments that

proclaimed the splendour of his reign. The ‘Timurid’ model was to have a lasting

influence upon the idea of empire across the whole breadth of Middle Eurasia.

But, despite his ferocity, his military genius and his

shrewd adaptation of tribal politics to his imperial purpose, Tamerlane’s

system fell apart at his death. As he himself may have grasped intuitively, it

was no longer possible to rule the sown from the steppe and build a Eurasian

empire on the old foundations of Mongol military power. The Ottomans, the

Mamluk state in Egypt and Syria, the Muslim sultanate in northern India, and

above all China were too resilient to be swept away by his lightning campaigns.

Indeed Tamerlane’s death marked in several ways the end of a long phase in

global history. His empire was the last real attempt to challenge the partition

of Eurasia between the states of the Far West, Islamic Middle Eurasia and

Confucian East Asia. Secondly, his political experiments and ultimate failure

revealed that power had begun to shift back decisively from the nomad empires

to the settled states. Thirdly, the collateral damage that Tamerlane inflicted

on Middle Eurasia, and the disproportionate influence that tribal societies

continued to wield there, helped (if only gradually) to tilt the Old World’s

balance in favour of the Far East and Far West, at the expense of the centre.

Lastly, his passing coincided with the first signs of a change in the existing

pattern of long-distance trade, the East–West route that he had fought to

control. Within a few decades of his death, the idea of a world empire ruled

from Samarkand had become fantastic. The discovery of the sea as a global

commons offering maritime access to every part of the world transformed the

economics and geopolitics of empire. It was to take three centuries before that

new world order became plainly visible. But after Tamerlane no world-conqueror

arose to dominate Eurasia, and Tamerlane’s Eurasia no longer encompassed almost

all the known world.