In October 1740, Emperor Charles VI died. In his youth he

had held title as the Archduke Charles, claimant to the Spanish crown and for

whom the Habsburgs waged the War for the Spanish Succession. He left a single

heir, his daughter the Archduchess Maria Theresa.

The Holy Roman Empire was an elective monarchy. Charles VI, however, negotiated with the ruling houses of Europe and the magnates of his monarchy to accept Maria Theresa as his legitimate and rightful heir and the next empress. Having secured domestic recognition of his daughter’s right to succeed him, he also acquired international recognition embodied in the document, the Pragmatic Sanction. It did not work. As soon as he died, the Bavarian and Saxon electors competed for the crown; and King Frederick II of Prussia, newly ascended to the throne, rejected Maria Theresa’s legitimacy and invaded Silesia, wealthiest of the Habsburg territories. France did not enter the war, but a French auxiliary corps was dispatched to central Germany in accordance with the Treaty of Westphalia, “to defend German liberties.”

In 1745 the Quadruple Alliance was officially formed by Britain,

Austria, the Netherlands, and Saxony through the Treaty of Warsaw. With

the death of Holy Roman Emperor Charles VII, the Holy Roman Empire’s

throne again became con- tested. Prussian forces were able to maintain

their position in Silesia and southern Germany, with Austrian forces

unable to oust them. Francis I of Lorraine, the husband of Maria

Theresa, was elected Holy Roman emperor, a move opposed by the Prussians

and the Bavarians. Despite Prussian successes against Austrian forces,

Frederick recognized Francis I’s acquisition of the Habsburg throne in

the Peace of Dresden on December 25, 1745, while it was recognized by

the Austrians that Silesia was a Prussian province. This agreement ended

the Second Silesian War.

In southern Europe the war was characterized by Spanish and Italian

engagements, given Bourbon Spanish attempts to acquire territory in

Italy, particularly Milan, with Italian states divided in terms of their

loyalties. As Austrian forces ousted Spanish forces from northern

Italy, they occupied formerly independent Italian states, most notably

Genoa. In contrast, in northern Europe, British and Dutch forces engaged

French forces in defense of the Austrian Netherlands as well as their

own possessions. With a Swedish-Russian settlement made in 1743, Russian

forces, allied with Austria, marched from Moscow to the Rhine in 1746.

The overwhelmed French and Spanish forces were forced to come to terms

or continue fighting against the enlarged coalition. The Peace of

Aix-la-Chapelle, signed on October 18, 1748, formally ended the War of

the Austrian Succession. In the end, Prussia was able to retain Silesia

at the expense of Austria, which was the trigger of the whole conflict.

The Spanish royal family decided the war offered an

opportunity to reclaim Milan. Prince Philip of Bourbon, the youngest son of

Philip V and Elizabeth Farnese, needed a crown; and Milan, along with Parma,

suited him. A Spanish army landed in Tuscany-a neutral-and marched north to the

Padana Plain. Then, Philip V asked his son Charles VII of Naples to return the

army he lent him in 1733 to the Neapolitan and Sicilian thrones. Neapolitan

troops marched north to join the Spanish army.

France too required allies. They requested Piedmontese

permission to cross the Alps and march on Milan, but Charles Emmanuel III did

not want to involve his state in this conflict. He realized that, in case of a

French and Spanish victory, Piedmont would be caught between the Bourbons. It

meant the end of any autonomous policy and of any possible dream of expanding

his power in Italy. Moreover, he threatened the approaching Spanish army that

if it entered the Padana Plain, his army would its his route to Milan.

At the same time, Britain perceived the precarious situation

as a threat to the Balance of Power. Piedmont and Austria were alone against

much of Europe, save Russia. London therefore committed its resources to the

Habsburg cause. Charles Emmanuel received a £250,000 annual subsidy to keep his

army on a war footing. Then, a British squadron entered the Mediterranean under

Admiral Matthews, ordered to act in support of Charles Emmanuel. The British

ships entered Naples harbor with some five thousand marines. Charles VII knew

it. He had no fleet and very few men to defend the city because his army had

marched north. So, when Matthews presented an ultimatum: recall all his

regiments with the Spanish army, or the city would be shelled and the marines

landed, Charles VII had little recourse but to accept the terms.

The defection of Naples eased Charles Emmanuel’s army action

against the Spanish in the Padana Plain. Not wanting to face isolation, the

Spanish withdrew through the Papal States along the Adriatic coast. Soon after,

Charles Emmanuel countermarched rapidly to meet a second Spanish army entering

Savoy via France. He won the campaign, but it was clear that the war was

becoming harder to manage.

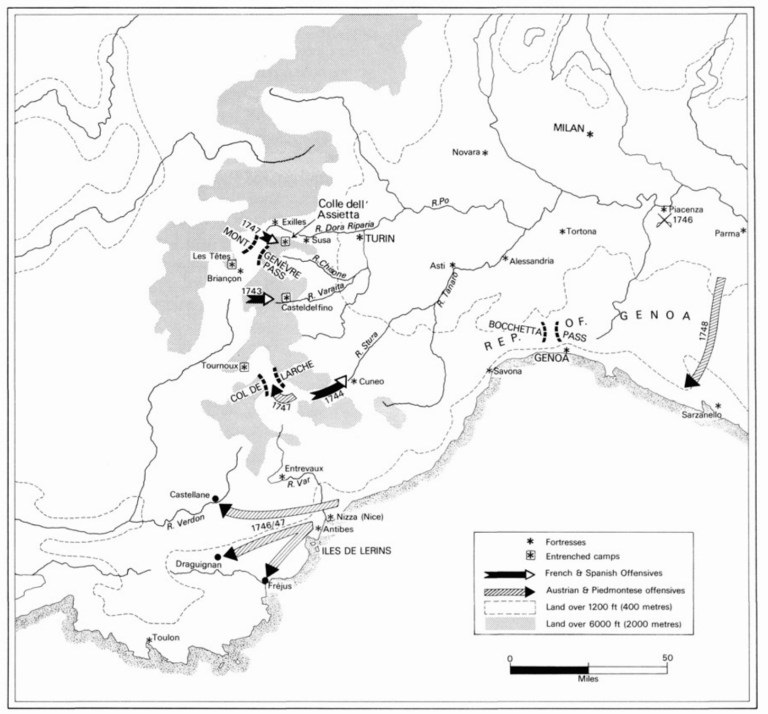

In 1743 the Spanish threatened Piedmont with two armies.

Charles Emmanuel possessed no more than 42,000 men and could use only half

against each Spanish army. Nonetheless, he crushed Prince Philip’s army,

marching from France, at Casteldelfino. Simultaneously, the Piedmontese with

their Habsburg allies fought and defeated the second army under de Gages at

Camposanto, on the other side of Italy and pressed it to the Neapolitan-Papal

States border on the Adriatic coast, where it sought refuge from the Neapolitan

king.

In the autumn of 1743, Britain joined Piedmont and Austria

in a formal league. The treaty signed in Wörms widened the scope of the

conflict from Europe to Asia, Africa, and America, where it was known as King

George’s War.

The 1744 campaign was hard fought. Unfortunately, Maria

Theresa wanted Naples because, according to the Peace of Utrecht, it should

have remained in Habsburg hands, yet the War of Polish Succession had reversed

that agreement.

Charles Emmanuel warned the Austrian ruler that this would

only increase the strategic dilemma. Why expand the conflict when victory was

not in sight? Regardless of the free advice, she ordered her army to destroy de

Gages’s Spanish army still waiting on the Neapolitan frontier. Charles VII of

Naples, aware of the Austrian menace, declared war and once again united his

troops with his father’s army.

An Austrian army marched south, passing through the Papal

States from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian coast. Charles VII gathered the

Spanish and Neapolitan army and encamped near Velletri, south of Rome. The

Austrians attacked in August and were repulsed with great loss.

The defeat forced the Habsburgs to abandon central Italy in

November. The Neapolitan-Spanish army followed on their heels, arriving in

northern Italy. What a present for Charles Emmanuel, who had his own troubles.

In fact, France officially entered the war in that same

year. A French army united with Prince Philip’s army passed the Alps, defeated

the local Piedmontese resistance, and besieged Cuneo. Charles Emmanuel tried to

relieve the city, but failed. He then directed the militia against the enemy’s

ordnance and supply lines and, thanks to these guerrilla tactics and to Cuneo’s

resistance, the Bourbon armies raised the siege and withdrew to France to take

winter quarters.

In the early days of 1745, Genoa entered the conflict. The

Most Serene Republic sought neutrality, just as Venice had done for the third

time in forty-five years. Unfortunately, while Venice could defend its

neutrality with 40,000 men, Genoa could not; and, moreover, Britain and Austria

promised to give Charles Emmanuel the Marquisate of Finale, a little imperial

fief in Liguria owned by the republic as a feudatory of the empire. Charles

Emmanuel desired it as a port, an additional window to the Mediterranean.

In order to protect its territory, Genoa signed a treaty in

Aranjuez and joined the Bourbon alliance. It was a disaster for Charles

Emmanuel. The Genoese accession to the League provided the Spanish-French army

with an opened route from France through Genoese territory, and now they could

mass the army from France with the army from Naples via Velletri, adding to it

10,000 Genoese troops. This was the real disaster as it increased the powerful

Bourbon army to 90,000 men.

As the war in Flanders continued, Charles Emmanuel received

no support from Austria.

He had a mere 43,000 men. Maneuvering them well to avoid

battle, he lost many fortresses but preserved his army. Despite this, he was

compelled to accept an armistice in December 1745. Fortunately, Prussia

accepted peace terms offered by Austria, allowing Vienna to send 12,000 men to

Italy. It was not an impressive army, but enough to permit Charles Emmanuel to

take the field upon the expiration of the armistice. In the spring 1746 he

attacked and the Bourbons were defeated. Milan was reconquered, Piedmont

liberated, and Genoa overrun by the Austrians. The Piedmontese army occupied

western Liguria and the French and Spanish fled, abandoning the republic.

While Charles Emmanuel prepared an invasion of southern

France, he sent a regiment to support the Corsican revolution against Genoese

rule.

Charles Emmanuel had no troops to stem the invasion. He

scraped together what troops he could find. On July 19, 1747, at Assietta Hill,

30,000 French with artillery attacked 5,400 Piedmontese and 2,000 Austrians. At

sunset, the French had lost 5,800 men and left more than 600 wounded1 to the

victorious defenders. General Count Bricherasio lost only 192 Piedmontese and

27 Austrians; it was clearly a triumph.

Assietta Hill was the last battle of the war on the Italian

front. A peace was signed on October 30, 1748, at Aix-la-Chapelle. 2 Everything

remained as it was before the war, except that Prince Philip of Spain obtained

the duchy of Parma and Charles Emmanuel received from Maria Theresa two West

Lombardy provinces, Vigevano, and Anghiera County, and a part of the territory

of Pavia, setting the Milanese-Piedmontese border along the Ticino river.