As more centralized governments developed during the Later

Middle Ages (1000-1500), significant changes took place in the way armies were

raised. This included the more extensive use of mercenaries and led to the

development of Europe’s professional armies.

While members of the nobility continued to fight primarily

as the result of social and feudal obligations, other soldiers increasingly

fought for pay. Although in theory some vassals in the later Middle Ages were

obliged to serve their lord annually for up to 40 days in the field, if they

had the financial ability they would often pay someone to serve in their stead.

The limited service requirements of feudal obligations could also cause severe

problems concerning a lord’s ability to sustain prolonged warfare. Once a

vassal’s required service was over, he could theoretically withdraw if

alternative arrangements had not been made. Thus, in addition to calling up

their vassals, wealthier lords and kings often employed mercenaries. Successful

use of mercenaries was usually dependent on their morale, as they were prone to

flee when battles went poorly or pay was tardy. Finally, cities sometimes

recruited armies from local populations or, if recruitment efforts were

unsuccessful, raised armies through conscription.

Once an army was raised, the issue of logistics was

paramount. Supply was so important that it often determined the makeup and size

of armies. Among the most important members of an army’s leadership was the

marshal, whose duties included marshaling, or gathering, the forces; organizing

the army’s heavy weapons; and providing for the army’s constant provisioning.

While all soldiers were responsible for providing their personal arms and

armor, the leadership was obliged to provide weapons beyond the pocketbook of

the common soldier, such as siege engines. Moreover, although soldiers would

bring an initial supply of rations for themselves, the army’s leadership was

responsible for plotting a route that allowed for resupply. This was done by

maintaining supply chains, purchasing supplies from local populations, or, more

often than not, foraging (plundering). Whatever the mean of provisioning, food

and drink were a constant worry and often in short supply.

Medieval European armies were normally arranged in three sections (battles or battalions) that included a vanguard, a main body, and a rear guard. The vanguard was the forward division of the army, usually comprised of archers and other soldiers who wielded long-range weapons. Their purpose was to inflict as much damage as possible on an opposing army before the main bodies, composed of infantry and armored cavalry, clashed. The main body comprised the bulk of the army’s forces, and its performance was usually crucial to the army’s success. The rear guard was usually comprised of less heavily armored and more agile cavalry, often mounted sergeants who could move quickly around the battlefield and chase down fleeing enemy soldiers. It also guarded the main force’s rear as well as the army’s supplies and camp followers (noncombatants who accompanied the army). Each section deployed in either a linear or block formation depending on the situation on the battlefield. While a block formation could better withstand cavalry charges, a linear formation allowed nearly the entire army to take part in a battle.

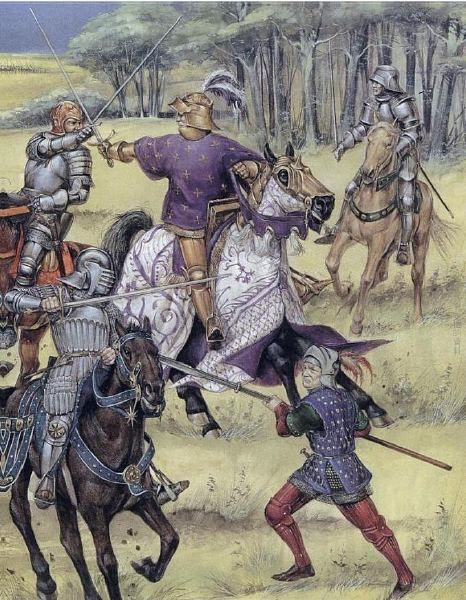

The importance of the mounted knight in medieval armies was

foundational to Europe’s social order. The prohibitive cost of proper arms,

armor, and horses limited knighthood primarily to the landed feudal class. The

typical knight was generally much more effective on the battlefield than the

common infantryman, as he was not only better equipped but also better trained.

Knights were usually placed in command of the cavalry (many of whom were less

well-armed sergeants from lower social classes), which was used primarily to

overrun enemy positions and break up enemy formations. If the cavalry charge

was successful, infantry was positioned to exploit any break in the enemy line.

The infantry was composed of pikemen, archers, crossbowmen,

swordsmen, and others who fought on foot and were usually joined by knights and

other cavalry who had lost their horses. While some infantry were experienced

warriors, many were poorly trained and only sporadically went into combat under

the leadership of their local lords. Pikemen defended against enemy cavalry by

pointing a concentrated number of pikes (long spears) in the direction of an

onrushing cavalry charge, while archers could fill the sky with arrows to

devastate the ranks of their approaching opponents. After several volleys, the

archers could step aside to allow the cavalry and other infantry to engage

their then weakened opponents. When the main bodies of two armies clashed on

the battlefield, infantrymen armed with swords, battle-axes, and similar weapons

provided screening for the cavalry and were essential for hand-to-hand combat.

As the battlefield became chaotic, communication was usually limited to audible

commands (sometimes produced by musical instruments), messengers, or visual

signals that included the use of banners, standards, or flags.

The development of effective siege warfare was necessitated

by the common use of defensive walls to protect medieval cities. Many cities

also contained a keep, or elevated fortification, for additional protection in

case the walls were breached by an enemy. Medieval strategists understood that

the most effective way for an army to overcome defensive walls was simply to

knock them down and rush through any openings. This was less risky than

maneuvers that involved scaling ladders while fending off the attacks of

defenders who benefited from their elevated position. Consequently, a variety

of powerful siege engines that included the mangonel, the ballista, and the

trebuchet were used to launch heavy projectiles at resisting cities and batter

their defenses. Additionally, attacking armies used siege towers to position

soldiers on a level equal to those defending a city wall, while forces on the

ground would also employ battering rams to knock down gates or sappers to

undermine walls.

Archers also played an important role in siege warfare.

Talented marksmen could wreak havoc on the opposing armies of both sides. The

skill and range of archers defending a city’s walls determined the placement of

the attacking army’s camp, as it was important to make sure that the attackers

were out of range of arrows. In the case of those who used the powerful English

longbow rather than the more common short bow, archers had a much higher rate

of fire and effective range, which made them especially valuable for use in

siege warfare and by the vanguard on the battlefield.

Technological developments also aided armies defending

cities or castles under siege. Concentric castles were developed during the

period of the crusades, as were architectural improvements, such as the round

tower, to make walls stronger and more defensible. Deeper wells allowed better

access to water during lengthy sieges, and small openings in the wall for

defending archers provided them protected positions. Attackers were also

repelled from city walls with boiling oil or water as well as molten lead. Yet

the most revolutionary changes in tactics, strategy, equipment, and

organization emerged with the introduction of gunpowder to European

battlefields in the fourteenth century. Powerful cannon tipped siege warfare in

favor of the attacking army, while hand cannon and other firearms made the

armor of knights obsolete. This led to the diminished importance of the mounted

nobility, which contributed to the rise of full-time professional armies in the

early modern period.

Renaissance Fortifications

The walls of Nicosia (1567) are a typical example of

Italian Renaissance military architecture that survives to this day.

At the beginning of the Renaissance, fortifications had to

be completely reconsidered as a result of developments in artillery. During the

Middle Ages, well-stocked fortresses with a source of potable water stood a

fairly good chance of resisting siege warfare. Such assaults usually began in

the spring or early summer, and hostile troops returned home at the onset of

cold weather if success did not appear imminent. Because repeated artillery

bombardment of medieval structures often yielded rapid results, warfare

continued year-round by the latter 15th century. Even though winter might be

approaching, military commanders persisted in barrages of artillery as long as

supplies were available for their troops, certain that they could break the

siege in a few more days or weeks. A new type of defensive fortification was

needed, and it was designed in Italy.

Early Renaissance

Medieval fortified structures consisted of high walls and

towers with slot windows, constructed of brick or stone. These buildings were

designed to withstand a long siege by hostile forces. The only ways to capture

such a fortification were (1) to roll a wooden siege tower against the wall and

climb over, but such towers were quite flammable and could be threatened by

fiery objects catapulted over the wall; (2) to batter down part of the wall,

under an assault of arrows, hot pitch, and other weapons hailing down from

above; and (3) to tunnel under the foundation, a process that could take a very

long time. Conventional towers and high walls were no match for artillery

bombardment, which could be accomplished from a distance with no threat to the

invading army. In addition, the walls and towers of medieval fortifications

were not equipped for the placement and utilization of heavy defensive

artillery. During the 15th century, European towns began to construct low,

thick walls against their main defensive walls, permitting pieces of artillery

to be rolled along the top and positioned as needed. The outer walls were often

sloped outwardly or slightly rounded to deflect projectiles at unpredictable

angles back toward the enemy. Bulwarks, usually U-shaped formations of earth,

timber, and stone, were built to protect the main gate and to provide defensive

artillery posts. In both central and northern Europe, many towns constructed

gun towers whose sole purpose was the deployment of defensive artillery. These

structures had guns at several levels, but usually lighter, lower caliber

weapons than those used on the walls. Heavier weapons would have created

unbearable noise and smoke in the small rooms in which they were discharged. In

several conventional medieval towers, the roof was removed and a gun platform

install.

Later Renaissance

Near the close of the 15th century, Italian architects and

engineers invented a new type of defensive trace, improving upon the bulwark

design. In the “Italian trace” [trace italienne -Star fort] triangle-shaped

bastions with thick, outward-sloping sides were pointed out from the main

defensive wall, with their top at the same level as the wall. At Civitavecchia,

a port near Rome used by the papal navy, the city walls were fortified with

bastions in 1520-the first example of bastions completely circling a defensive

wall. Bastions solved several problems of the bulwark system, especially with

bastions joined to the wall and not placed a short distance away, where troops

could be cut off by enemy troops. The most important improvement was the

elimination of the blind spot caused by round towers and bulwarks; gunners had

a complete sweep of enemy soldiers in the ditches below. Development of the

bastion design in Italy was a direct response to the 1494 invasion by the

troops of Charles VIII and the superior artillery of France at that time, and

to continued threats from the Turks. Bastion-dominated fortifications were

constructed along the Mediterranean coast to create a line of defense against

naval attacks. Several such fortifications were built in northern Europe,

beginning with Antwerp in 1544. In some instances fortifications were not

feasible, for reasons such as very hilly terrain or opposition from estate

owners reluctant to lose property, and in some regions military threat was not

extreme enough to warrant the effort of constructing new fortifications. In

such cases, an existing fortress might be renovated and strengthened to create

a citadel. Municipalities often opposed construction of citadels, which

symbolized tyranny, because they were imposed on defeated cities by warlords.

Citadels proved to be an effective means, however, for providing a protective

enclosure during enemy attacks. By the mid-16th century, the expense of

fortifications was exorbitant. Henry VIII, for example, was spending more than

one-quarter of his entire income on such structures, and the kingdom of Naples

was expending more than half.

THE DEVELOPMENT AND INFLUENCE OF FIREARM

After countless unsuccessful experiments, lethal accidents

and ineffective trials, firearms research and techniques gradually improved, and

chroniclers report many types of guns—mainly used in siege warfare—with

numerous names such as veuglaire, pot-de-fer, bombard, vasii, petara and so on.

In the second half of the 14th century, firearms became more efficient, and it

seemed obvious that cannons were the weapons of the future. Venice successfully

utilized cannons against Genoa in 1378. During the Hussite war from 1415 to

1436, the Czech Hussite rebels employed firearms in combination with a mobile

tactic of armored carts (wagenburg) enabling them to defeat German knights.

Firearms contributed to the end of the Hundred Years’ War and allowed the

French king Charles VII to defeat the English in Auray in 1385, Rouen in 1418

and Orleans in 1429. Normandy was reconquered in 1449 and Guyenne in 1451.

Finally, the battle of Chatillon in 1453 was won by the French artillery. This

marked the end of the Hundred Years’ War; the English, divided by the Wars of

the Roses, were driven out of France, keeping only Calais. The same year saw

the Turks taking Constantinople, which provoked consternation, agitation and

excitement in the whole Christian world.

In that siege and seizure of the capital of the Eastern

Roman empire, cannon and gunpowder achieved spectacular success. To breach the

city walls, the Turks utilized heavy cannons which, if we believe the

chronicler Critobulos of Imbros, shot projectiles weighing about 500 kg. Even

if this is exaggerated, big cannons certainly did exist by that time and were

more common in the East than in the West, doubtless because the mighty

potentates of the East could better afford them. Such monsters included the

Ghent bombard, called “Dulle Griet”; the large cannon “Mons Berg” which is

today in Edinburgh; and the Great Gun of Mohammed II, exhibited today in

London. The latter, cast in 1464 by Sultan Munir Ali, weighed 18 tons and could

shoot a 300 kg stone ball to a range of one kilometer.

A certain number of technical improvements took place in the

15th century. One major step was the amelioration of powder quality. Invented

about 1425, corned powder involved mixing saltpeter, charcoal and sulphur into

a soggy paste, then sieving and drying it, so that each individual grain or

corn contained the same and correct proportion of ingredients. The process

obviated the need for mixing in the field. It also resulted in more efficient

combustion, thus improving safety, power, range and accuracy.

Another important step was the development of foundries,

allowing cannons to be cast in one piece in iron and bronze (copper alloyed with

tin). In spite of its expense, casting was the best method to produce practical

and resilient weapons with lighter weight and higher muzzle velocity. In about

1460, guns were fitted with trunnions. These were cast on both sides of the

barrel and made sufficiently strong to carry the weight and bear the shock of

discharge, and permit the piece to rest on a two-wheeled wooden carriage.

Trunnions and wheeled mounting not only made for easier transportation and

better maneuverability but also allowed the gunners to raise and lower the

barrels of their pieces.

One major improvement was the introduction in about 1418 of

a very efficient projectile: the solid iron shot. Coming into use gradually,

the solid iron cannonball could destroy medieval crenellation, ram

castle-gates, and collapse towers and masonry walls. It broke through roofs,

made its way through several stories and crushed to pieces all it fell upon.

One single well-aimed projectile could mow down a whole row of soldiers or cut

down a splendid armored knight.

About 1460, mortars were invented. A mortar is a specific

kind of gun whose projectile is shot with a high, curved trajectory, between

45° and 75°, called plunging fire. Allowing gunners to lob projectiles over

high walls and reach concealed objectives or targets protected behind

fortifications, mortars were particularly useful in sieges. In the Middle Ages

they were characterized by a short and fat bore and two big trunnions. They

rested on massive timber-framed carriages without wheels, which helped them withstand

the shock of firing; the recoil force was passed directly to the ground by

means of the carriage. Owing to such ameliorations, artillery progressively

gained dominance, particularly in siege warfare.

Individual guns, essentially scaled down artillery pieces

fitted with handles for the firer, appeared after the middle of the 14th

century. Various models of portable small arms were developed, such as the

clopi or scopette, bombardelle, baton-de-feu, handgun, and firestick, to

mention just a few.

In purely military terms, these early handguns were more of

a hindrance than an asset on the battlefield, for they were expensive to

produce, inaccurate, heavy, and time-consuming to load; during loading the

firer was virtually defenseless. However, even as rudimentary weapons with poor

range, they were effective in their way, as much for attackers as for soldiers

defending a fortress.

The harquebus was a portable gun fitted with a hook that

absorbed the recoil force when firing from a battlement. It was generally

operated by two men, one aiming and the other igniting the propelling charge.

This weapon evolved in the Renaissance to become the matchlock musket in which

the fire mechanism consisted of a pivoting S-shaped arm. The upper part of the

arm gripped a length of rope impregnated with a combustible substance and kept

alight at one end, called the match. The lower end of the arm served as a

trigger: When pressed it brought the glowing tip of the match into contact with

a small quantity of gunpowder, which lay in a horizontal pan fixed beneath a

small vent in the side of the barrel at its breech. When this priming ignited, its

flash passed through the vent and ignited the main charge in the barrel,

expelling the spherical lead bullet.

The wheel lock pistol was a small harquebus taking its name

from the city Pistoia in Tuscany where the weapon was first built in the 15th

century. The wheel lock system, working on the principle of a modern cigarette

lighter, was reliable and easy to handle, especially for a combatant on

horseback. But its mechanism was complicated and therefore expensive, and so

its use was reserved for wealthy civilian hunters, rich soldiers and certain

mounted troops.

Portable cannons, handguns, harquebuses and pistols were

muzzle-loading and shot projectiles that could easily penetrate any armor.

Because of the power of firearms, traditional Middle Age weaponry become

obsolete; gradually, lances, shields and armor for both men and horses were

abandoned.

The destructive power of gunpowder allowed the use of mines

in siege warfare. The role of artillery and small firearms become progressively

larger; the new weapons changed the nature of naval and siege warfare and

transformed the physiognomy of the battlefield. This change was not a sudden

revolution, however, but a slow process. Many years elapsed before firearms

became widespread, and many traditional medieval weapons were still used in the

16th century.

One factor militating against artillery’s advancement in the

15th century was the amount of expensive material necessary to equip an army.

Cannons and powder were very costly items and also demanded a retinue of

expensive attendant specialists for design, transport and operation.

Consequently firearms had to be produced in peacetime, and since the Middle

Ages had rudimentary ideas of economics and fiscal science, only a few kings,

dukes and high prelates possessed the financial resources to build, purchase,

transport, maintain and use such expensive equipment in numbers that would have

an appreciable impression in war.

Conflicts with firearms became an economic business

involving qualified personnel backed up by traders, financiers and bankers as

well as the creation of comprehensive industrial structures. The development of

firearms meant the gradual end of feudalism. Firearms also brought about a

change in the mentality of combat because they created a physical and mental

distance between warriors. Traditional mounted knights, fighting each other at

close range within the rules of a certain code, were progressively replaced by

professional infantrymen who were anonymous targets for one another, while

local rebellious castles collapsed under royal artillery’s fire. Expensive

artillery helped to hasten the process by which central authority was restored.

Mercenaries

The collapse of the monetary economy in Western Europe

following the fall of Rome left just two areas where gold coin was still used

in the 10th century: southern Italy and southern Spain (al-Andalus). Ready gold

drew mercenaries to wars in those regions as carrion creatures draw near dead

flesh. Also able to pay in coin for military specialists and hardened veterans

was the Byzantine Empire, along with the Muslim states it opposed and fought

for several centuries. The rise of mercenaries in Western Europe in the 11th

century as a money economy resumed disturbed the social order and was received

with wrath and dismay by the clergy and service nobility. Early forms of

monetary service did not necessarily involve straight wages. They included fief

money and scutage. But by the end of the 13th century paid military service was

the norm in Europe. This meant that local bonds were forming in many places and

a concomitant sense of “foreignness” attached to long-service soldiers.

Mercenaries were valued for their military expertise but now feared and

increasingly despised for their perceived moral indifference to the causes for

which they fought. Ex-mercenary bands (routiers, Free Companies) were

commonplace in France in the 12th century and a social and economic scourge

wherever they moved during the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453). Their main

weapon was the crossbow, on land and at sea. In the galley wars of the

Mediterranean many Genoese, Pisan, and Venetian crossbowmen hired out as

specialist marine archers. Much of the Reconquista in Spain was fueled by the

mercenary impulse and concomitant necessity for armies to live off the land.

The hard methods and cruel attitudes learned by Iberians while fighting Moors

were then applied in the Americas by quasi-mercenary conquistadores.

Mercenaries- “condottieri,” or foreign “contractors”-also played a major part

in the wars of the city-states of the Italian Renaissance.

French “gen d’armes” and Swiss pikemen and halberdiers

fought for Lorraine at Nancy (1477). By the start of the 15th century Swiss

companies hired out with official Cantonal approval or as free bands who elected

their officers and went to Italy to fight as condottieri. With the end of the

wars of the Swiss Confederation against France and Burgundy, Swiss soldiers of

fortune formed a company known as “das torechte Leben” (roughly, “the mad

life”) and fought for pay under a Banner displaying a town idiot and a pig.

Within four years of Nancy some 6,000 Swiss were hired by Louis XI. In 1497,

Charles VIII (“The Affable”) of France engaged 100 Swiss halberdiers as his

personal bodyguard (“Garde de Cent Suisses”). In either form, the Swiss became

the major mercenary people of Europe into the 16th century. “Pas d’argent, pas

de Suisses” (“no money, no Swiss”) was a baleful maxim echoed by many

sovereigns and generals. Mercenaries of all regional origins filled out the

armies of Charles V, and those of his son, Philip II, as well as their enemies

during the wars of religion of the 16th and 17th centuries. By that time Swiss

mercenaries who still used pikes (and many did) were largely employed to guard

the artillery or trenches or supplies. Similarly, by the late 16th century

German Landsknechte were still hired for battle as shock troops but they were

considered undisciplined and perfectly useless in a siege.

In Poland in the 15th century most mercenaries were

Bohemians who fought under the flag of St. George, which had a red cross on a

white background. When Bohemian units found themselves on opposite sides of a

battlefield they usually agreed that one side would adopt a white cross on a

red background while their countrymen on the other side used the standard

red-on-white flag of St. George. In the Polish-Prussian and Teutonic Knights

campaigns of the mid-15th century the Brethren-by this point too few to do all

their own fighting-hired German, English, Scots, and Irish mercenaries to fill

out their armies. During the “War of the Cities” (1454-1466) German mercenaries

were critical to the victory of the Teutonic Knights at Chojnice (September 18,

1454). When the Order ran out of money, however, Bohemian soldiers-for-hire who

held the key fortress and Teutonic capital of Marienburg for the Knights sold

it to a besieging Polish army and departed, well paid and unscathed by even a

token fight.

Condottierie

From the end of the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282-1302),

the Italians tried to decide for themselves what government they wanted,

resulting in conflict between the Ghibellines-who supported Imperial rule-and

the Guelfs-who supported papal rule. The Guelfs were successful in the first

decade of the fourteenth century, ironically at much the same time the papacy

moved to Avignon in 1308. Suddenly freed from either Imperial or papal

influence, the large number of sovereign states in northern and central Italy

began to try to exert control over their neighbors. Florence, Milan, and

Venice, and to a lesser extent Lucca, Siena, Mantua, and Genoa, all profited

from the early-fourteenth-century military situation by exerting their

independence. But this independence came at a price. The inhabitants of the

north Italian city-states had enough wealth to be able to pay for others to

fight for them and they frequently employed soldiers, condottieri in their

language (from the condotte, the contract hiring these soldiers) and

mercenaries in ours. Indeed, the immense wealth of the Italian city-states in

the late Middle Ages meant that the number of native soldiers was lower than

elsewhere in Europe at the same time, but it meant the cost of waging war was

much higher.

One might think that having to add the pay for condottieri

to the normal costs of war would have limited the numbers of military conflicts

in late medieval Italy. But that was not the case and, in what was an

incredibly bellicose time, Italy was one of the most fought over regions in

Europe. Most of these wars were small, with one city’s mercenary forces facing

another’s, but they were very frequent. They gave employment to a large number

of condottieri, who in turn fought the wars, which in turn employed the

condottieri. An obvious self-perpetuating circle developed. It was fueled by a

number of factors: the wealth of northern Italy; the greed of wealthier

Italians to acquire more wealth by occupying neighboring cities and lands (or

to keep these cities from competing by incorporating their economies); their

unwillingness themselves to fight the wars; and the availability of a large

number of men who were not only willing to do so, but who saw regular

employment in their mercenary companies as a means to comfort, wealth, and often

titles and offices. In 1416, one condottierie, Braccio da Montone, became lord

of Perugia, while a short time later two others, condottieri sons of the

condottiere Muccio Attendolo Sforza, Alessandro and Francesco, became the

Master of Pesaro and Duke of Milan, respectively. Other condottieri became

governors of Urbino, Mantua, Rimini, and Ferrara during the fifteenth century.

Venice and Genoa continued to be the greatest rivals among

the northern Italian city-states. Both believed the Mediterranean to be theirs,

and they refused to share it with anyone, including Naples and Aragon, nor, of

course, with each other. This became a military issue at the end of the

fifteenth century. The common practice was a monopoly trading contract.

Venice’s monopoly with the crusader states ceased when the crusaders were

forced from the Middle East in 1291, although they were able to sustain their

trade with the victorious Muslim powers. And Venice’s contract with

Constantinople was abandoned with the fall of the Latin Kingdom in 1261, only

to be replaced by a similar contract with Genoa that would last till the city’s

fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

Frequently during the late Middle Ages, this rivalry turned

to warfare, fought primarily on the sea, as was fitting for two naval powers.

Venice almost always won these engagements, most notably the War of Chioggia

(1376-1381), and there seems little doubt that such defeats led to a weakening

of the political independence and economic strength of Genoa. Although Venice

never actually conquered Genoa, nor does it appear that the Venetian rulers

considered this to be in their city’s interest, other principalities did target

the once powerful city-state. Florence held Genoa for a period of three years

(1353-1356), and Naples, Aragon, and Milan vied for control in the fifteenth

century. Seeking defensive assistance, the Republic of Genoa sought alliance

with the Kingdom of France, and it is in this context that their most prominent

military feature is set, the Genoese mercenary. During the Hundred Years War,

Genoa supplied France with naval and, more famously, crossbowmen mercenaries,

the latter ironically provided by a city whose experience in land warfare was

rather thin.

Before the fifteenth century, the Republic of Venice had also

rarely participated in land campaigns-except for leading the forces of the

Second Crusade in their attack of Constantinople in 1204. Seeing the sea not

only as a provider of economic security but also as defense for the city,

Venetian doges and other city officials had rarely pursued campaigns against

their neighbors. However, in 1404- 1405, a Venetian army, once again almost

entirely mercenaries, attacked to the west and captured Vicenza, Verona, and

Padua. In 1411-1412 and again in 1418-1420, they attacked to the northeast,

against Hungary, and captured Dalmatia, Fruili, and Istria. So far it had been

easy-simply pay for enough condottieri to fight the wars, and reap the profits

of conquest. But in 1424 Venice ran into two Italian city-states that had the

same military philosophy they did, and both were as wealthy: Milan and

Florence. The result was thirty years of protracted warfare.

The strategy of all three of these city-states during this

conflict was to employ more and more mercenaries. At the start, the Venetian

army numbered 10,000-12,000; by 1432 this figure had grown to 18,000; and by

1439 it was 25,000, although it declined to 20,000 during the 1440s and 1450s.

The other two city-states kept pace. At almost any time after 1430 more than

50,000 soldiers were fighting in northern Italy. The economy and society of the

whole region were damaged, with little gain by any of the protagonists during

the war. At its end, a negotiated settlement, Venice gained little, but it also

lost very little. The city went back to war in 1478-1479, the Pazzi War, and

again in 1482-1484, the War of Ferrara. The Florentines and Milanese

participated in both as well.

After the acquisition of Vicenza, Verona, and Padua in 1405

Venice shared a land frontier with Milan. From that time forward Milan was the

greatest threat to Venice and her allies, and to practically any other

city-state, town, or village in northern Italy. Milan also shared a land

frontier with Florence, and if Milanese armies were not fighting Venetian armies,

they were fighting Florentine armies, sometimes taking on both at the same

time.

Their animosity predates the later Middle Ages, but it

intensified with the wealth and ability of both sides to hire condottieri. This

led to wars with Florence in 1351-1354 and 1390-1402, and with Florence and

Venice (in league together) in 1423-1454, 1478-1479, and 1482-1484. In those

rare times when not at war with Florence or Venice, Milanese armies often

turned on other neighboring towns, for example, capturing Pavia and Monza among

other places.

Perhaps the most telling sign of Milan’s bellicosity is the

rise to power of its condottiere ruler, Francesco Sforza, in 1450. Sforza had

been one of Milan’s condottieri captains for a number of years, following in

the footsteps of his father, Muccio, who had been in the city-state’s employ

off and on since about 1400. Both had performed diligently, successfully, and,

at least for condottieri, loyally, and they had become wealthy because of it.

Francesco had even married the illegitimate daughter of the reigning Duke of

Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti. But during the most recent wars, after he had

assumed the lordship of Pavia, and in the wake of Filippo’s death in 1447, the

Milanese decided not to renew Francesco’s contract. In response, the

condottiere used his army to besiege the city, which capitulated in less than a

year. Within a very short time, Francesco Sforza had insinuated himself into

all facets of Milanese rule; his brother even became the city’s archbishop in

1454, and his descendants continued to hold power in the sixteenth century.

Genoa, Venice, and Milan all fought extensively throughout

the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but Florence played the most active

role in Italian warfare of the later Middle Ages. A republican city-state,

although in the fifteenth century controlled almost exclusively by the Medici

family, Florence had been deeply involved in the Guelf and Ghibelline conflicts

of the thirteenth century, serving as the center of the Guelf party. But though

the Guelfs were successful this did not bring peace to Florence and when, in

1301, they split into two parties-the blacks and the whites-the fighting

continued until 1307. Before this feud was even concluded, however, the

Florentine army, numbering 7,000, mostly condottieri, attacked Pistoia,

capturing the city in 1307. In 1315 in league with Naples, Florentine forces

attempted to take Pisa, but were defeated. In 1325, they were again defeated

while trying to take Pisa and Lucca. Between 1351 and 1354 they fought the

Milanese. From 1376 to 1378 they fought against papal forces hired at and drawn

from Rome in what was known as the War of the Eight Saints, but the Florentines

lost more than they gained. Forming the League of Bologna with Bologna, Padua,

Ferrara, and other northern Italian cities, they warred against Milan from 1390

to 1402. While they were initially successful against the Milanese, Gian

Galeazzo, Duke of Milan, was eventually able to bring Pisa, Lucca, and Venice

onto his city’s side, and once again Florence was defeated. In 1406 Florence

annexed Pisa without armed resistance. But war broke out with Milan again in

1423 lasting until 1454; Florence would ally with Venice in 1425, and with the

papacy in 1440. Battles were lost on the Serchio in 1450 and at Imola in 1434,

but won at Anghiara in 1440. Finally, after the Peace of Lodi was signed in

1454 ending the conflict, a league was formed between Florence, Venice, and

Milan that lasted for 25 years. But, after the murder of Giuliano de’ Medici

and the attempted murder of his brother, Lorenzo-Pope Sixtus IV was complicit

in the affair-war broke out in 1478 with the papacy and lasted until the death

of Sixtus in 1484. In addition, interspersed with these external wars were

numerous rebellions within Florence itself. In 1345 a revolt broke out at the

announcement of the bankruptcy of the Bardi and Peruzzi banking firms; in 1368

the dyers revolted; in 1378 there was the Ciompi Revolt; and in 1382 the popolo

grasso revolt. None of these were extensive or successful, but they did disrupt

social, economic, and political life in the city until permanently put to rest

by the rise to power of the Medicis.

Why Florence continued to wage so many wars in the face of

so many defeats and revolts is simple to understand. Again one must see the

role of the condottieri in Florentine military strategy; as long as the

governors of the city-state were willing to pay for military activity and as

long as there were soldiers willing to take this pay, wars would continue until

the wealth of the town ran out. In Renaissance Florence this did not happen.

Take, for example, the employment of perhaps the most famous condottiere, Sir

John Hawkwood. Coming south in 1361, during one of the lulls in fighting in the

Hundred Years War, the Englishman Hawkwood joined the White Company, a unit of

condottieri already fighting in Italy. In 1364, while in the pay of Pisa, the

White Company had its first encounter with Florence when, unable to effectively

besiege the city, they sacked and pillaged its rich suburbs. In 1375, now under

the leadership of Hawkwood, the White Company made an agreement with the

Florentines not to attack them, only to discover later that year, now in the

pay of the papacy, that they were required to fight in the

Florentine-controlled Romagna. Hawkwood decided that he was not actually

attacking Florence, and the White Company conquered Faenza in 1376 and Cesena

in 1377. However, perhaps because the papacy ordered the massacres of the

people of both towns, a short time later Hawkwood and his condottieri left

their papal employment. They did not stay unemployed for long, however;

Florence hired them almost immediately, and for the next seventeen years, John

Hawkwood and the White Company fought diligently, although not always

successfully, for the city. All of the company’s condottieri became quite

wealthy, but Hawkwood especially prospered. He was granted three castles

outside the city, a house in Florence, a life pension of 2,000 florins, a

pension for his wife, Donnina Visconti, payable after his death, and dowries

for his three daughters, above his contracted pay. Florentines, it seems, loved

to lavish their wealth on those whom they employed to carry out their wars,

whether they were successful or not.

In comparison to the north, the south of Italy was

positively peaceful. Much of this came from the fact that there were only two

powers in southern Italy. The Papal States, with Rome as their capital, did not

have the prosperity of the northern city-states, and in fact for most of the

later Middle Ages they were, essentially, bankrupt. But economic problems were

not the only matter that disrupted Roman life. From 1308 to 1378 there was no

pope in Rome and from then until 1417 the Roman pontiff was one of two (and

sometimes three) popes sitting on the papal throne at the same time. But even

after 1417 the papacy was weak, kept that way by a Roman populace not willing

to see a theocracy return to power. Perhaps this is the reason why the Papal

States suffered so many insurrections. In 1347 Cola di Rienzo defeated the

Roman nobles and was named Tribune by the Roman people. He governed until those

same people overthrew and executed him in 1354. In 1434 the Columna family

established a republican government in the Papal States, forcing the ruling

pope, Eugenius IV, to flee to Florence. He did not return and reestablish his

government until 1343. Finally, in 1453, a plot to put another republican

government in place was halted only by the general dislike for its leader, Stefano

Porcaro, who was executed for treason.

One might think that such political and economic turmoil

would not breed much military confidence, yet it did not seem to keep the

governors of the Papal States from hiring mercenaries, making alliances with other

Italian states, or pursuing an active military role, especially in the central

parts of Italy. Usually small papal armies were pitted against much larger

northern city-state forces, yet often these small numbers carried the day,

perhaps not winning many battles, but often winning the wars, certainly as much

because of the Papal States alliances as its military prowess. This meant that

despite all the obvious upheaval in the Papal States during the later Middle

Ages, at the beginning of the 1490s it was much larger and more powerful than

it had ever been previously.

Bibliography Contamine, Philippe. War in the Middle

Ages. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984. France, John. Western Warfare in the Age

of the Crusades, 1000-1300. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999. Lepage,

Jean-Denis G. G. Medieval Armies and Weapons in Western Europe: An Illustrated

History. Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland, 2005. Nicholson, Helen. Medieval

Warfare. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. Nicolle, David. French Medieval

Armies, 1000-1300. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 1991.