Austro-Hungarian Emperor Karl’s promise of a two-pronged

offensive flew in the face of warnings that Field Marshal Boroević (his new

rank) had sent to the high command since the end of March. Karl and his chief

of staff hoped to make Rome negotiate, and enlarge their spoils when Germany

won the war. Boroević did not believe the Central Powers could win. Instead of

wasting its strength on needless offensives, Austria should conserve it to deal

with the turmoil that peace would unleash in the empire.

But Karl and the high command were adamant: there must be an

offensive. Boroević prepared a plan to attack across the River Piave, towards

Venice and Padua. Yet again, Conrad argued for an attack from the Asiago

plateau: if successful, this would make the Piave line indefensible and force

another Italian retreat. He urged the Emperor to attack on both sectors, and

Karl gave way. Preparations began on 1 April with a view to attacking on 11

June.

Boroević had seen Cadorna make this very mistake time and

again, attacking on too broad a front. He spoke up again: if they had to attack

on both sectors, the high command should send reinforcements. In mid-May, he repeated

his warning that it was irresponsible to attack without enough shells and with

troops ill-equipped and famished. By way of reply, the high command told

Boroević to confirm that he would be ready by 11 June. Not before the 25th, he

replied. The date was set for 15 June.

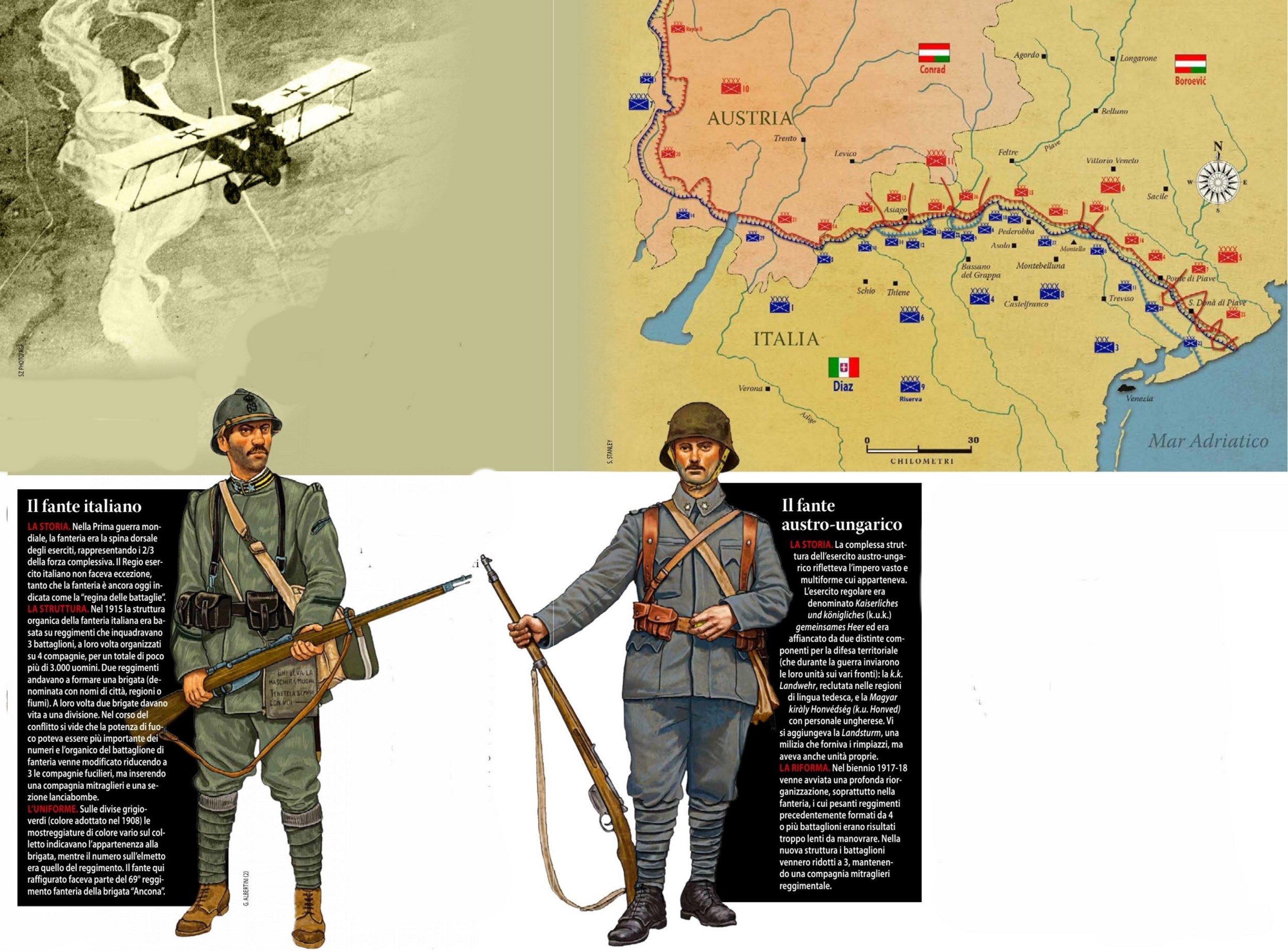

On paper, the Austrian army looked strong enough. With

Russia out of the war, most of the 53 divisions with a further ten in reserve

could be kept in Italy, which was now the empire’s major front. However, the

infantry divisions were down from 12,000 to 8,000 or even 5,000 men. New

battalions were at roughly half strength. Some 200,000 Hungarian soldiers had

deserted in the first three months of 1918. In the spring, Karl approved the

call-up of the class of 1900; the new intake would be boys of 17, plus older

men returning after convalescence. Cavalry divisions were even more depleted.

The railways were dilapidated from over use, and motor vehicles lacked fuel.

The industrial capacity of the empire had never been strong;

by 1917, output was declining under the double impact of battlefield casualties

and the Allied blockade. In 1918, the decline became a slump. Production of

artillery weapons and shells halved in the first half of the year, compared

with 1917. Production of rifles fell by 80 per cent in the same period.

Uniforms were tattered, there was no new underwear, and worn-out boots could

not be replaced. Food shortages helped to trigger a general strike in January.

The stoppages spread until 700,000 workers were crying for peace, justice and

bread. Radical Socialists exploited the hardship caused by hunger, war taxes

and inflation. (‘In Russia, the land, the factories and the mines are being

given to the people.’) The mainstream Social Democrats, however, decided not to

support the calls for revolution; instead they negotiated with the government.

Even so, the army had to send forces from the front to ensure order. February

brought the first significant mutiny, by naval crews in Montenegro. Food

shortages and officers’ privileges were the trigger, and the unrest spread up

the Adriatic coast. Hopes that cooperation with newly independent Ukraine would

unlock huge imports of grain came to nothing. April brought food riots in

Laibach and ‘mass rallies at which oaths for unity and independence were being

sworn’. By now, seven divisions were deployed in the interior of the empire.

The army was not cushioned against the shortages. By 1918,

it was getting only half the flour it needed. The daily rations of front-line

troops in Italy were reduced in January to 300 grams of bread and 200 grams of

meat. Even these statistics only tell half the story. A Czech NCO, Jan Triska

of the 13th Artillery Regiment, recorded the real conditions. The rations had

run out during the Caporetto offensive, and matters had grown much worse since

then. The army was ordered to provision itself from the occupied territory.

This was only possible for a month or two; in February, Boroević told the Army

High Command that the situation was critical: the men had been hungry for four

weeks, and were ‘no longer moved by incessant empty phrases that the hinterland

is starving or that we must hold out’. They must be properly fed if they were

to fight.

By late April, the men were starving. Bread and polenta were

very scarce, and often mixed with sawdust or even sand. Meat practically

disappeared. Soldiers stole the prime cuts from horses killed by enemy fire,

and orders went out for carcasses to be delivered directly to the

slaughterhouse. Triska’s battery horses were dying; only six of 36 were

healthy. Even the coffee made of chicory was in short supply. ‘Salt was only a

memory.’ The men were often given money instead of food, but there was nothing

to spend it on. The men grew so weak during May that they could only walk with

difficulty. Triska risked punishment by trading his service revolver and

ammunition for horsemeat. He collected stems of grass to boil and eat, and

picked mulberries when they could be found. Such was the condition of the men

who were sent against the Italians in June.

#

With 23 undersized divisions on the Asiago plateau, another

15 on the line of the Piave and 22 more in reserve, the Habsburg force barely

outnumbered the Italians, who had a clear advantage in firepower and in the

air. The offensive would start on the Piave, where Boroević’s divisions would

attack across the river. Conrad’s divisions were to follow up by striking from

the north.

Addressing his officers, Boroević openly criticised the

shortages of men and supplies. Due to Conrad’s stubbornness, he implied, the

Piave line was short of ten divisions. After this rare indiscretion, the field

marshal did his duty, ordering his battalion commanders to attack like a

hurricane and not pause until they reached the River Adige. ‘For this,

gentlemen, could well be the last battle. The fate of our monarchy and the

survival of the empire depend on your victory and the sacrifice of your men.’

It has been claimed that, despite everything, Habsburg morale ran high in June.

Certainly, there are reports of soldiers marching to the line with maps of

Treviso in their pockets, gaily asking the bystanders how far it was to Rome.

They would have taken heart from the order to plunder the Allied lines (no

shortages there). Different testimony came from Pero Blašković, commanding a

Bosnian battalion on the Piave. According to Blašković, a Habsburg loyalist to

the bone, everyone without exception hoped the offensive would be postponed,

for they were all aware of Karl’s muted search for a separate peace. It was

this, more than hunger or lack of munitions, Blašković says, that took the

men’s minds off victory, making them reflect that defeat would cost fewer

lives, letting more of them get safely home in the end.

The bombardment began at 03:00 on 15 June. As at Caporetto,

the Austrians aimed to incapacitate the enemy batteries with a pinpoint attack,

including gas shells. However, their accuracy was poor, due to Allied control

of the skies; many of the shells may have been time-expired, and the Italians

had been supplied with superior British gas-masks. Too many Austrian guns were

deployed in the Trentino, a secondary sector; some heavy batteries had no

shells at all; and there was no element of surprise, for Diaz’s army had agents

in the occupied territory, and deserters were talkative. The Austrian gunners

only had the advantage on the Asiago plateau, where thick fog blanketed the preparations.

At 05:10, the guns lengthened their fire to strike the

Italian rear lines and reserves. The pontoons were dragged out from behind the

gravel islands near the river’s eastern shore. The enemy batteries were still

silent; perhaps the gas shells had knocked them out? No such luck; the Italian

guns opened up, pounding the Austrian jump-off positions. The Italian riverbank

was still wreathed in gas fumes when the assault teams jumped ashore, quickly

taking the Italian forward positions amid the chatter of machine guns.

The morning went well; the Austrians moved 100,000 men

across the river under heavy rain. Watching the infantry pour over the

pontoons, Jan Triska and his gunners wondered if this time they would reach

Venice. Enlarging the bridgeheads proved more difficult. Progress was made on

the Montello, where the four divisions pushed forward several kilometres, and

around San Donà, near the sea. Elsewhere, the attackers were pinned down near

the river. Further north, Conrad’s divisions attacked from Asiago towards Mount

Grappa. Slight initial gains could not be held; the Italians had learned how to

use the ‘elastic defence’, absorbing enemy thrusts in a deep system of

trenches, then counter-attacking. By the end of the day, Blašković realised,

‘our paper house had been blown down’. The Emperor sent Boroević a desperate

telegram: ‘Hold your positions, I implore you in the name of the monarchy!’ The

answer was curt: ‘We shall do our best.’

Progress on the second day was no easier. Conrad was in

retreat; his batteries – more than a third of all the Habsburg guns in Italy –

were out of the fight. Boroević ordered his commanders to hunker down while

forces were transferred from the north. Meanwhile the Piave rose again, washing

away many of the pontoons. Supplying the bridgeheads across the torrent became

even more dangerous. The Austrians were too close to exhaustion and their

supplies too uncertain for a sustained battle to run in their favour. By the

first afternoon, Major Blašković realised that the Austrian artillery, laying

down a rolling barrage for the assault troops, were already husbanding their

shells. If the under-used Italian units further north were to be redeployed

around Montello, the Habsburg goose would soon be cooked. Overhead, the Caproni

aeroplanes chased away the Habsburg planes and British Sopwith Camels proved

their worth, bombing along the river. (‘In aviation, too, morale is very

important,’ Blašković remarked sadly, ‘but technology is even more so.’) The

pontoons and columns of men on the riverbank, waiting to cross, offered easy

targets. While the Austrians ran out of shells, the Allied artillery and air

bombardment were unrelenting. The fate of Jan Triska’s battery on the Piave was

indicative: over the week of battle, it lost 58 men, half its strength.

Conrad’s divisions were too hard pressed to transfer men to

the Piave. In fact, the opposite happened: the Italians transferred forces from

the mountains to the river. When these reinforcements arrived, on 19 June, the

Italians counter-attacked along the Piave. They failed to crack the

bridgeheads, but the Austrian position was untenable. Pontoons that had

survived the bombing were damaged by high water and debris. Blašković’s

regiment (the 3rd Bosnia & Herzegovina Infantry) ran out of shells and

bullets; the men fought on with bayonets and hand-grenades until a Hungarian

regiment managed to bring up a few crates of ammunition from the river.

Boroević told the Emperor that if the Montello could be

secured, it should be the springboard for a new offensive. Securing it would

need at least three more divisions, including artillery. If the high command

did not intend to renew the offensive from the Montello, it was pointless to

retain the bridgeheads; they should be abandoned and all efforts dedicated to

strengthening the defences east of the river. As Karl wondered what to do, the

German high command stepped in, ordering a cessation of hostilities so that the

Austrians could despatch their six strongest divisions to the Western Front.

For Ludendorff’s spring offensives were running out of steam and 250,000

American troops were arriving every month. Karl consulted his commanders in the

field, who echoed Boroević’s stark choice: either reinforce or withdraw. Then

he consulted his chief of the general staff, General Arz von Straussenberg. A

new offensive within a few weeks was, they agreed, not a realistic prospect.

Their reserves were almost used up; even if enough divisions could be

transferred to the Piave from elsewhere – and none could safely be spared from

Ukraine or the Balkans – the Italians would match them. It would not be

possible to recapture the zest of 15 June without a lengthy recovery.

Late on the 20th, Karl ordered the right bank of the Piave

to be abandoned. General Goiginger, commanding the corps that had performed so

well on the Montello, refused to obey. They had taken 12,000 prisoners and 84

guns; how could they retreat? Eventually he submitted, and the withdrawal

began. Both sides were exhausted, and the manoeuvre was completed without much

fighting. The Bosnians and Hungarians on the Montello worked their way back to

the river. The last Austrians crossed on 23 June, ending the Battle of the

Solstice. The Italians had lost around 10,000 dead, 35,000 wounded and more

than 40,000 prisoners, against 118,000 Habsburg dead, wounded, sick, captured

and missing. Early in July, Third Army units capped the achievement by seizing

the swampy delta at the mouth of the Piave which the Austrians had held since

Caporetto.

The rejoicing was widespread and spontaneous. For many

soldiers, the Battle of the Solstice cleansed the stain of Caporetto, and the

name of the Piave has ever since evoked a glow of fulfilment, as smooth as the

sound of its utterance, untouched by the horrors of the Isonzo front or the

controversy that overshadowed Italy’s victory in November. Ferruccio Parri, a

much-decorated veteran who became a leading antifascist, said at the end of his

long life that the Battle of the Solstice was ‘the only proper national battle

of which our country can truly be proud’.

For the Allies, two things were clear: the Italians were a

fighting force again, and the Austro-Hungarian army was still dangerous: its

morale had not collapsed and the soldiers were still loyal. The view inside

Boroević’s army was different; to their eyes, the civilian system had let them

down. They were still better soldiers than the Italians, but what could they do

without food or munitions? The spectacle of his own men after the battle filled

the genial Blašković with despair: ‘weary, dejected and starving, their

tattered uniforms crusted with reddish dry clay. Their weapons alone gave them

any likeness to soldiers, for otherwise they looked like beggars roaming from

pillar to post.’ Gloom settled over the Austrian lines.