The strength of the Byzantine Empire lay in its

disciplined heavy cavalry – the cataphracts. Both men and horses were trained

to a high degree, and were capable of carrying out complex drills on the

battlefield. As well as proficiency in the lance, cataphracts were adept in the

use of their bows.

CATAPHRACT CAVALRY

The Byzantine cataphract – from the Greek word for

“covered” – was equipped with full metal-scale armor, which extended

to the horse as well as the rider. The Parthians had been the first army to

make use of cataphracts, and their Roman opponents were sufficiently impressed

to create heavy cavalry units of their own. The Byzantines later made the

cataphracts the major strike force within their army. Mounted on a powerful

warhorse, the Byzantine cataphract bristled with weapons, which included a bow,

lance, sword, and even a dagger. Besides body armor he wore an iron helmet and

carried a shield, the latter strapped to the arm so he could use both hands to

control his horse. The main cataphract tactic depended on shock action – a

ferocious charge that could crash through virtually any enemy.

The strength of the sixth-century Byzantine army was undoubtedly its cavalry. The majority were equipped equally for shock action or for fighting from a distance. These horsemen wielded lance or bow as the situation demanded, but although the riders were heavily armoured, their horses do not seem to have been protected. The Strategikon emphasized the need for cavalry to charge in a disciplined manner, always maintain a reserve of fresh troops, and be careful not to be drawn into a rash pursuit. Bucellarii were normally cavalry, and by their nature horsemen were more suited than foot soldiers to the raids and ambushes which dominated the warfare of this period. The sixth-century cavalryman was far more likely to experience combat than his infantry counterpart. In a largescale action a well-balanced mix of horse and foot was still the ideal, but the Roman infantry of this period had a very poor reputation. In part this was a result of their inexperience, but they often seem to have lacked discipline and training. N ars’es used dismounted cavalrymen to provide a reliable centre to his infantry line at Taginae. At Dara Belisarius protected his foot behind specially prepared ditches. Roman infantry almost invariably fought in a defensive role, providing a solid base for the cavalry to rally behind. They did not advance to contact enemy foot, but relied on a barrage of missiles, javelins, and especially arrows, to win the combat. All units now included an element of archers and it was claimed that Roman bows shot more powerfully than their Persian counterparts. The front ranks of a formation wore armour and carried large round shields and long spears, but some of the ranks to the rear carried bows. Infantry formations might be as deep as sixteen ranks. Such deep formations made it difficult for soldiers to flee, but also reduced their practical contribution to the fighting, and were another indication of the unreliability of the Roman foot soldier. The Strategikon recorded drill commands given in Latin to an army that almost exclusively spoke Greek. There were other survivals of the traditional Roman military system, many of which would endure until the tenth century, but the aggressive, sword-armed legionary was now a distant memory.

In 541, the Byzantine hold on Italy was seriously threatened

by Totila, the new Ostrogoth king. Raising the banner of rebellion, Totila

advanced as far south as Naples before being stopped.

After he had taken Naples, Totila laid siege to Rome.

Belisarius was sent back to Italy. Rome was taken by Totila in December 546.

The Byzantine forces were left holding only four fortresses in Italy.

Belisarius returned again to Constantinople and was replaced by Justinian’s

Court Chamberlain, Narses, a man who conducted his generalship less with

flamboyance than with the precision of a mathematician. In the meantime Totila

had taken Sicily again and manned 300 ships to control the Adriatic. By the

spring of 552 Narses had mobilized his forces fully, composed mainly of

Barbarian contingents, Huns, Lombards, Persians and others. Finding his way

south blocked by Teia and his Gothic warriors at Verona, he outflanked them by

marching close to the Adriatic coast, reaching Ravenna safely. When Totila

received the news in the vicinity of Rome, he took almost his entire army,

crossed Tuscany, and established his base at the village of Taginae, the

present day Tadino.

The Byzantine reconquest of Italy proved short-lived. In

568, the Lombards invaded Italy and forced the Byzantines into the southern

part of the peninsula. However, southern Italy and Sicily remained Byzantine

until the advent of the Normans. The Byzantine reconquest of Spain, completed

in 554, was somewhat more successful. The empire held the southern third of the

Iberian Peninsula until 616, when the Visigoths reclaimed their lost

territories.

#

Byzantine Emperor Justinian had finally realized that he

could not succeed in Italy without a major effort, in which an able general

would have to be placed in command of adequate forces. Still jealous of

Belisarius, he first selected his nephew Germanius, who had distinguished

himself as a subordinate of Belisarius in Persia and who had recently won a

substantial victory over the Slavs. Germanius, however, died near Sardica, so

Justinian selected the aged eunuch Narses (478-573) for command in Italy.

Narses refused to accept the post without adequate forces. When he marched

north from Salona, later that year, he probably had a total force of

20,000-30,000 men. Arriving in Venetia, he discovered that a powerful

Gothic-Frank army at least 50,- 000 strong, under the Goth leader Teias and the

Frank King Theudibald, blocked the principal route to the Po Valley. Not wishing

to engage such a formidable force and confident that the Franks would soon tire

of their alliance with the Goths, as they had in the past, Narses cleverly

skirted the lagoons along the Adriatic shore by using his vessels to leapfrog

his army from point to point along the coast, some going by ship, some

marching, in a manner similar to a modern truck and foot march. In this way he

arrived at Ravenna without encountering any opposition. Near Ravenna he

attacked and crushed a small Gothic force at Rimini.

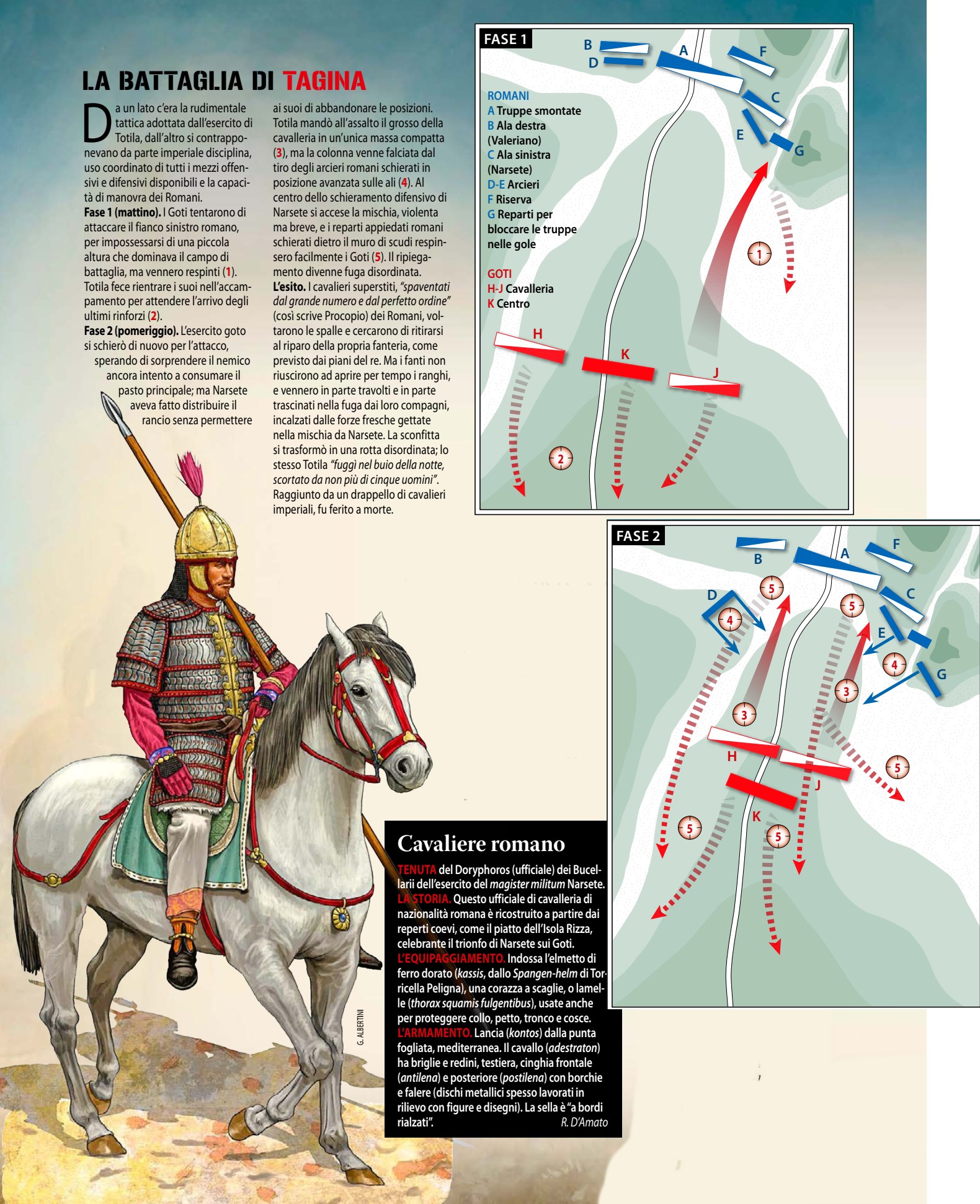

Narses now began an advance on Rome. Crossing the Apennines

with nearly 20,000 men, he was met by Totila, who probably did not have more

than 15,000. In a narrow mountain valley suitable for the shock tactics of his

heavy cavalry lancers, Totila had chosen a position which Narses could not

bypass. Totila first tried to compensate for his weakness in numbers by

attempting to seize a hill from which he could outflank the enemy position, but

he was stopped by a unit of 50 Roman infantry.

The imperial general immediately deployed his army in a

concave formation. He dismounted his Lombard and Heruli cavalry mercenaries,

placing them as a phalanx in the center. His heavy Roman cavalry cataphracts

were on each flank, reinforced with all his infantry-who were foot archers. On

his left he sent out a mixed force of foot and horse archers to seize a

dominant height.

Totila delayed while waiting for an additional 2,000 cavalry

to join him, then, after attempts to draw out the Romans had failed, he

launched an attack after the midday meal.

Totila’s army was in two lines: the heavy cavalry lancers in

the front, with his archers and a line of spear and axe-wielding infantry

behind. The Goths opened the battle with a determined cavalry charge. As they

swept down the valley they first came under the fire of the advanced force on

Narses’ left, then rode into the cross fire of the archers in his concave

wings. Halted by the devastating fire, the attackers were then thrown back in

confusion on the infantry advancing behind them. Efforts of the Gothic archers

to support their cavalry were foiled by the more aggressive, more mobile

imperial horse archers on the flanks. Covered by continued fire from the foot

archers, these heavy cataphracts then swept into the milling mass of Goths in a

double envelopment. More than 6,000 of them, including Totila, were killed. The

remnants fled. Narses then continued on to Rome, which he captured after a

brief siege.

Man traditionally identified as Narses, from the

mosaic depicting Justinian and his entourage in the Basilica of San Vitale,

Ravenna.

NARSES

BYZANTINE GENERAL

BORN 478

DIED 573

KEY CONFLICTS Gothic War

KEY BATTLES Taginae 552, Vesuvius 553, Volturnus 554

Born in Armenia, Narses was a court eunuch in the Byzantine

imperial palace in Constantinople. In 532, when riots threatened Emperor

Justinian, he was commander of the imperial guard, but this was a court rather

than a military appointment. In 538 Narses was chosen to lead an army to

reinforce Belisarius fighting the Ostrogoths in Italy. He had no military

experience, but the ageing eunuch was intended to control Belisarius, whom

Justinian distrusted, rather than to win battles.

Yet Narses was to turn into an outstanding battlefield

leader. His first visit to Italy was short, his constant disagreements with

Belisarius too disruptive of military operations. But in the 540s he was given

a real command, in charge of an army of Heruli – Germanic troops – whom he soon

led to an important victory over raiding Slavs and Huns in Thrace.

In 552 Narses led another army to Italy to fight the

Ostrogoths once more. Unlike Belisarius he was given plenty of troops. Though a

shrivelled 74-year-old, he provided them with inspiration and organization. At

Taginae he defeated the Ostrogoth leader, Totila, retook Rome, and finally

crushed the Gothic army at a second battle in the foothills of Vesuvius. Narses

had regained Italy in a single lightning campaign. In 554 he won another great

victory, defeating the Franks and Alamanni tribes at Volturnus. He was still

defending Italy against Goths and Franks in 562, when old age ended his

unlikely military career.