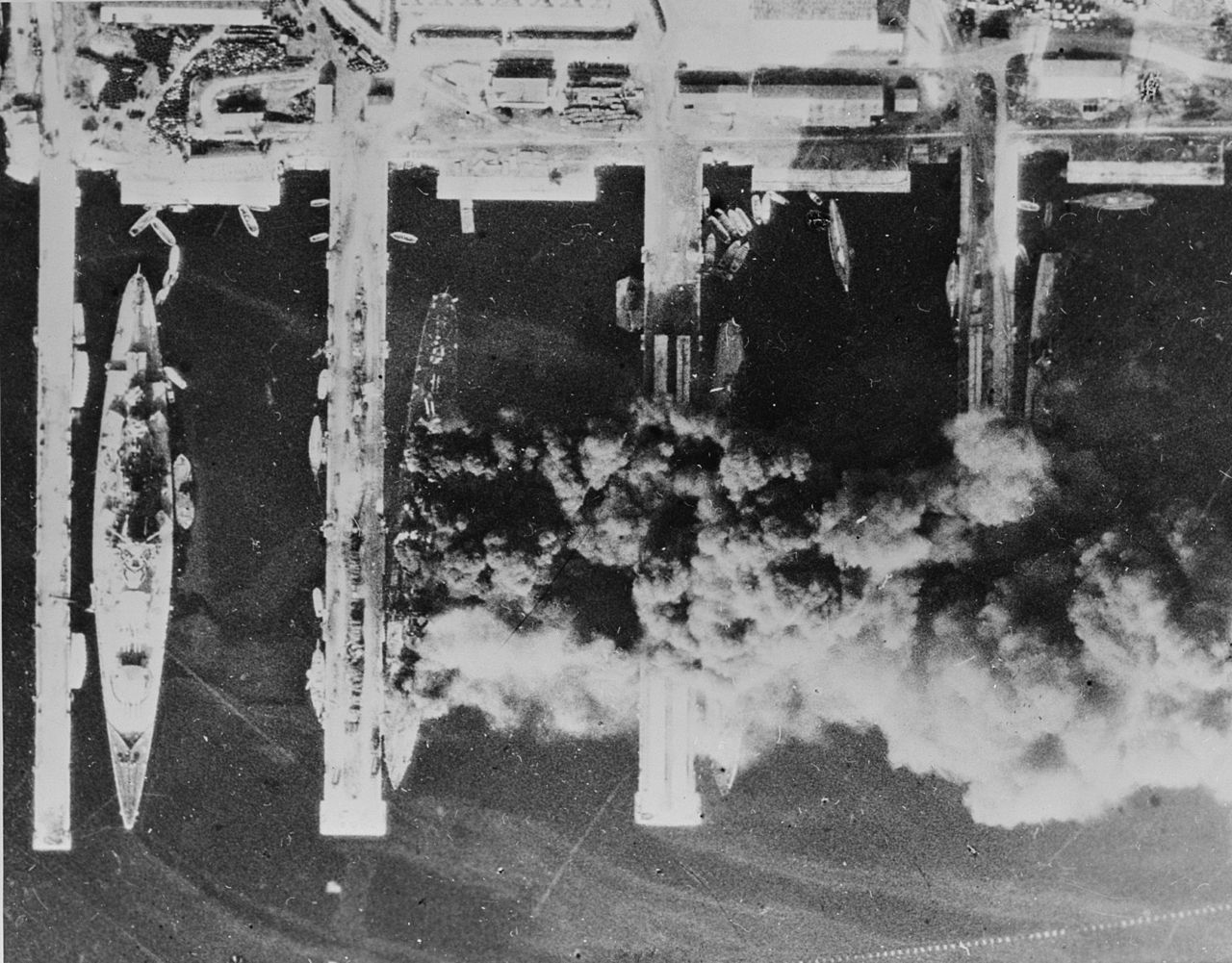

The scuttled French fleet at Toulon: aerial pictures.

On 28 November 1942, the day after the scuttling and firing of the ships of the

French fleet in Toulon harbour, photographs were taken by the Royal Air Force.

Many of the vessels were still burning so that smoke and shadows obscure part

of the scene. But the photographs show, besides the burning cruisers, ship

after ship of the contre-torpilleurs and destroyer classes lying capsized or

sunk, testifying to the thoroughness with which the French seamen carried out

their bitter task. While the vast damage done is shown in these photographs, no

exact list of the state of the ships can be drawn up, since the ships

themselves cannot be seen in an aerial photograph. Thus the upper deck of the

battle cruiser Strasbourg is not submerged, but here are signs that the vessel

has settled and is grounded. The key plan C.3296 shows the whereabouts of the

majority of the ships and their condition as far as it can be seen from the

photographs. Picture shows: damaged and sunk light cruisers and destroyers

visible through the shadow and the smoke caused by the burning cruisers.

left is the

Strasbourg (bridge above the water but clearly sunk)

next to her,

burning, is the Colbert

under the

smoke, the Algérie

to the

right, the Marseillaise.

Positions of the main ships during the operation

Darlan’s decision to order a cease-fire in North Africa

placed the Vichy leader, Marshal Pétain, in an impossible situation. Pétain

immediately countermanded Darlan’s order and declared his action illegal, but

too late. The Germans realized just how vulnerable they were if other Vichy

officers were to take a similar line as soon as Allied forces approached, and

within days had occupied the Vichy zone libre with some help from Italian

forces. Darlan had left secret orders for one of the commanders of the Vichy

French forces, Lieutenant-General Jean-Marie de Lattre de Tassigny, to resist

any German attempt to seize Vichy, and for his actions, de Lattre was

imprisoned by the Vichy regime. Otherwise, the Germans met little resistance,

and moved to disband the 100,000-strong army that had been permitted Vichy.

Occupying Vichy did not simply give the Germans additional

territory, it brought with it a tremendous dowry in that the largest part of

the French fleet was stationed at Toulon. There were some eighty ships there, a

force which on its own was larger than most of the world’s navies. Indeed, in

terms of the number of major surface units, it came close to matching Germany’s

own, although by this time the German U-boat fleet had overtaken the French

submarine fleet in terms of numbers. Toulon was the French fleet’s main port,

and the dockyard itself was well over a mile-and-a-half long and half-a-mile

deep.

At Toulon, two other French admirals were in command.

Admiral de la Borde commanded the larger warships that pre-war would have

constituted the Atlantic and Mediterranean Squadrons. He had been ordered by

Darlan to move his ships to Dakar, where they would have been out of reach of

the Germans and for the time-being at least, difficult for the Allies to take

over as well. When he received Darlan’s order, de la Borde’s response had been

brief, and to the point: ‘Merde!’ Admiral Marquis was the port admiral, but he

flew his flag in the elderly battleship Provence.

Under de la Borde’s command were the two powerful

battlecruisers, Strasbourg and Dunkerque, both 26,500 tons, although the latter

had been badly damaged in her encounter with Force H at Mers-el-Kebir. He also

had three obsolescent heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, ten large ‘super’ destroyers

of the contre-torpilleur type as well as three smaller destroyers. In addition

to Provence, Marquis also had the Commandant Teste, 10,000 tons seaplane

tender, two destroyers, four torpedo boats and ten submarines. In addition to

these ships, which seem to have been fully or nearly fully manned, there were

another two cruisers, eight contre-torpilleur destroyers, six smaller

destroyers and ten submarines that had actually been decommissioned under the

armistice terms and which simply had skeleton crews aboard. Apart from these,

there were also minesweepers and other minor naval vessels and auxiliaries.

This was a prize worth having.

The major fleet units, including the destroyers but not the

submarines, were steam-powered, which meant that steam had to be raised before

they could leave port. Since it could take eight hours to raise steam, once the

Germans were at the gates of the dockyard, flight was not an option.

It soon became clear that the Germans were occupying all

military and naval installations, and that Toulon could not be far down the

list. On 27 November 1942, the personnel at Toulon received the briefest

possible warning of what was intended, with German troops and tanks advancing

on the port, followed by German naval personnel who were obviously expected to

take over the ships.

As in most naval bases, the larger ships were lying

alongside the outermost piers with others lying alongside them, while five

ships were sitting in the large dry docks, including Dunkerque.

The Germans had intended to take the dockyards and the ships

by surprise, using a pincer movement with one group travelling along the road

from Nice while another three groups, including the crack Das Reich division

seized the Toulon peninsula and the town. While the dockyard had defensive

positions, including gun batteries outside the dockyard area, there were just

two gateways and a high wall to be passed as well. When Marquis was captured at

04.30, aroused from his sleep by an advance guard of German troops, his staff

had time to send a warning signal to de la Borde, although at first he refused

to believe that the Germans would attack the base. Nevertheless, he had the

presence of mind to immediately order all commanding officers to raise steam on

their ships, even though this would take several hours, and to be on their

guard to prevent the Germans boarding any vessel. Then the order to scuttle was

re-issued, and then repeated as the Germans attempted to enter the dockyard

area, but encountered fierce resistance from Vichy forces, who had also been

alerted by a dispatch rider sent by a gendarmerie outpost. In the confusion,

five submarines, Venus, Casablanca, Marsouin, Iris and Glorieux with their

diesel engines providing power almost immediately, managed to slip away and out

to sea. The ease with which they did this, their crews manning their deck

armament, suggests that the whole procedure had already been rehearsed.

Nevertheless, their escape wasn’t easy. They were bombed, strafed and depth

charged by the Luftwaffe, leaving Venus so damaged that she had to be scuttled,

while Iris, also damaged, was taken by her commanding officer and crew to

Spain, where they spent the rest of the war in internment. Nevertheless, the

other three boats reached North Africa.

After a German bulldozer forced its way through the main

gates, the act of scuttling those ships that could not flee was started.

Through the main gate at 05.00, the Germans took another hour to reach the

first of the ships, and when they reached the piers alongside which the Strasbourg

had been moored, they found that she was already drifting away after her crew

had cast of all lines to the shore. Admiral de la Borde was aboard his

flagship, and to discourage him from taking the ship to sea, which would have

been impossible, a German tank fired an 88mm shell into ‘B’ turret, fatally

wounding a gunnery officer. The crew responded, but with machine guns and other

light weapons. The officer in command of the German troops demanded that de la

Borde return his ship to the pier and hand her over to his forces, but de la

Borde replied that scuttling had already started, with her sea cocks opened and

the ship settling slowly in the water. Further communication was prevented by

the first of a series of loud explosions ripping through the ship. In addition

to setting explosive charges, the crew were also setting about wrecking the

ship’s machinery with hand grenades and oxy-acetylene cutters. There wasn’t

enough depth of water for the ship to sink completely, but instead she settled

on the bed of the port, leaving her distinctive superstructure sticking out of

the water.

Nearby, the crew of the heavy cruiser Algerie, 13,900 tons,

also had opened her sea cocks and her main armament had been destroyed by

explosives. This did not prevent a German officer from declaring to Admiral

Lacroix that he had come to seize the ship, only to be informed by a bemused

Lacroix that he was too late. A brief stand-off then occurred as the German

said that he would come aboard the Algerie if the ship would not blow up, to be

countered by Lacroix’s declaration that the ship would indeed be blown up if

the German boarded. Added emphasis came to the exchange a couple of minutes

later when one of the two after twin 8-in turrets blew up. The ship continued

to burn for the next two days during which occasional explosions could be heard

as her ammunition went up. This was far from a record, as the light cruiser

Marseillaise, which had settled at an angle, took more than a week to burn

herself out. Another cruiser, the Colbert, was boarded by a German party, but

when they saw fuses being set and one of her officers setting fire to his

floatplane, they left promptly, but only just in time before her magazine blew

the ship apart. The German party that had set foot aboard another cruiser, the

Dupleix, also had a narrow escape when she blew up.

Scuttling on its own often causes little damage, and ships

scuttled in shallow port waters can be re-floated and salvaged, which was one

reason why so much emphasis was given to setting off the magazines and ready

use ammunition, not to mention the attacks by grenade and oxy-acetylene

cutters. This point was brought home later when another cruiser, a sister ship

of the Marseillaise, La Galissonniere, was scuttled, but then re-floated and taken

by the Italian navy, although returned to the French in 1944.

In the confusion, the elderly battleship Provence was one

ship that was nearly taken by the Germans, as her commanding officer hesitated

when he was given the message that the Vichy premier, Pierre Laval, had ordered

that there were to be no ‘incidents’. Nevertheless, while he sent an officer to

seek clarification, his crew, seeing the other ships sinking and blowing up,

opened the sea cocks and the ship began to settle in the water even while the

Germans argued with her CO on the bridge.

Nevertheless, it was clear that there were to be victims

amongst the French ships. A ship in dry dock cannot be scuttled, and it is

usual, for the safety of dockyard workers, for ships entering dry dock to be de-stored.

The battlecruiser Dunkerque, sister ship of the Strasbourg and pride of the

pre-war French navy, was in dry dock and rather than being refitted and

returned to service, she suffered the ignominy of being scrapped by a large

gang of Italian workers imported for the purpose, so that she could be sent to

Italy in pieces as part of a scrap metal drive intended to rebuild Italy’s

dwindling stocks of war materials. The decision to scrap the ship was caused

not so much by the damage inflicted two years earlier by the Royal Navy, but by

the damage inflicted on her armament and turbines in the brief period between

the warning being given and the Germans finding their way to the ship.

Out of the eight contre-torpilleur destroyers, three, Lion,

Tigre and Panthere were being refitted and their skeleton crews did not have

enough time to sabotage them effectively, so these survived to pass to Italy

along with the smaller destroyer Trombe.

Despite having lost his ship, de la Borde was left aboard

the Strasbourg when she settled on the bottom of the harbour. He refused to go

ashore, remaining aboard and accusing the Germans of breaching the terms of the

armistice in attempting to seize the French fleet. Incredibly, the first

indication that French naval units in North Africa had of the events at Toulon

were when they picked up Pétain’s signal to de la Borde: ‘I learn at this

instant that your ship is sinking. I order you to leave it without delay.’

Meanwhile, the Germans had left de la Borde, reasoning that in theory he had

gone down with his ship. Certainly, he was no longer a threat.

Not all of the submarines had managed to escape, and the

four that were left behind at Toulon were scuttled at their moorings.

In the aftermath of the battle of Toulon and the attempted

seizure of the fleet, everyone on the base, including the ships’ crews, were

interned, effectively becoming prisoners of war. The Vichy authorities argued

that their actions were in accordance with the terms of the armistice, and for

once won the argument with the Germans. The internees were all released, and

the naval personnel spent the rest of their war on full pay from the Vichy

authorities!

ALEXANDRIA

The German attempt to grab the fleet at Toulon and Darlan’s orders led Cunningham to expect the French squadron in the Mediterranean, under Vice-Admiral Godfroy at Alexandria to reactivate his fleet, and join the Allies. ‘They have no excuse for remaining inert,’ he wrote home on 1 December 1942. ‘Except perhaps that so many Frenchmen at the present time appear to have lost all their spirit. Doubtless it will revive; but at present the will to fight for their country is completely absent.’