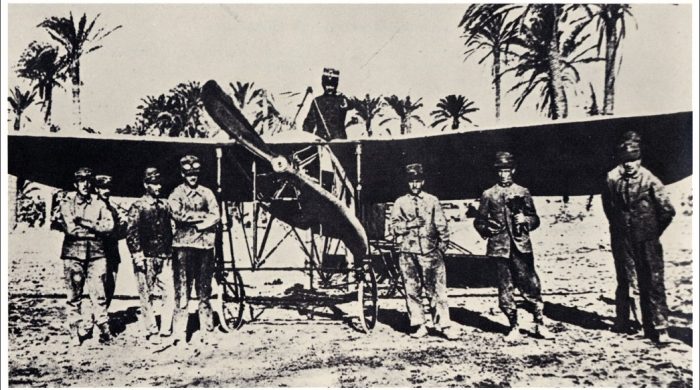

Bleriot XI (French, early WWI). Single-seat/two-seat

reconnaissance. Developed from Louis Bleriot’s 1909 cross-Channel monoplane;

existed in several sizes/ forms. Used in Italo-Turkish War 1911-12, Balkan

Wars, early months World War I; thereafter as trainer. 50hp or 80hp Gnome

engine; max. speed 75mph (120kph); makeshift armament of pistols and/or rifle

or carbine.

In the earliest air actions, carried out by Italian airmen in

Libya (Tripolitania), the bomb dropped by Lieut. Gavotti was a 2-kg

weapon like the one shown here: it was known as a Cipelli bomb, so named

after its inventor.

“Today I have decided to try to throw bombs from the aeroplane. It is the first time that we will try this and if I succeed, I will be really pleased to be the first person to do it,” wrote Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti to his father. With other military aviators of the new Italian Royal Army Air Services Specialist Battalion, Lt. Gavotti had been sent to the Ottoman Turk provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica to fight in the Italo-Turkish War. His aeroplane was a Blériot monoplane, one of only a handful in Italy’s possession.

“Today two boxes full of bombs arrived. We are expected to throw them from our planes. It is very strange that none of us have been told about this, and that we haven’t received any instruction from our superiors. So we are taking the bombs on board with the greatest precaution. It will be very interesting to try them on the Turks.”

The influence of World War I on the use of aeroplanes for military purposes has left a general impression that aerial warfare was originated during those fateful years. In fact, the true pioneers of air warfare in aeroplanes were a handful of courageous Italian airmen who served during the little-known Italo-Turkish War in Libya in 1911-12, almost three years before the commencement of the European conflict.

In August 1911 the Italian Army manoeuvres had shown a

potential for aircraft in general reconnaissance roles, and on 25 September

came an order to mobilise the Italian Special Army Corps and, more

significantly. an Air Flotilla. On that date the Flotilla comprised a total of

nine aeroplanes-two Bleriot XI monoplanes, two Henry Farman biplanes, three

Nieuport monoplanes, and two Etrich Taubes-manned by five first-line pilots,

six reserve pilots and 30 airmen for all forms of technical maintenance. All

nine machines were immediately dismantled, crated and sent by sea to Libya,

arriving in the Bay of Tripoli on 15 October. With minimum facilities available,

the crated aircraft were put ashore and transported to a suitable flying ground

nearby, where assembly commenced almost immediately. The first aeroplane was

completed by 21 October.

On the morning of 23 October 1911, Captain Carlos Piazza,

commander of the Air Flotilla, took off at 0619 hours in his Bleriot for an

urgently-requested reconnaissance of an advancing body of Turkish and Arab

troops and eventually landed back at base at 0720 hours. This was the first-ever

war flight in an aeroplane. Shortly after Piazza left, his second-in-command.

Captain Riccardo Moizo, piloting a Nieuport, also took off but returned after

40 minutes with little to report. Both men were airborne again on the following

day, seeking the location of enemy troops and, in Moizo’s case, being

successful.

Next day, 25 October, Moizo was again in the air and sighted

a large Arab encampment in the Ain Zara region. As he circled his objective,

Moizo was greeted with a barrage of rifle fire and three bullets pierced his

Nieuport’s wings. Though these caused no serious damage, it was the first

occasion on which an aeroplane had experienced hostile ground fire. Within the

following three days two more aircraft had become available. These-an Etrich

Taube, piloted by Second Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti, and a Henry Farman, by

Lieutenant Ugo de Rossi-soon joined their seniors on scouting patrols over

enemy camps and emplacements.

The Flotilla commander, Captain Piazza, quickly perceived

further roles for his aircraft and, after several unsuccessful attempts,

finally achieved a measure of air-to-ground co-operation with the local Italian

artillery commander; Piazza dropped messages of correction or confirmation (in

small tins) after observing the actual results of artillery fire. This presaged

a major role for aeroplanes in the imminent European war. Piazza also envisaged

the possibilities of aerial camera work and, on 11 November, sent an urgent

request to his headquarters for provision of a Zeiss Bebe plate camera. After

several weeks of waiting. Piazza took it upon himself to borrow a camera from

the Engineer Corps in Tripoli and had this fixed to his Bleriot, positioned

just in front of his seat and pointing downwards. Manipulation of the controls

and the plate camera at once meant that only one exposure could be made on each

flight, but it was the birth of airborne photo-reconnaissance.

The Turks, without any air arm, were forced on to the

defensive and retaliated by rifle and machine gun fire. Since the Italian

aviators could not fly very high, these weapons had some effect; one Italian

aircraft outside Tripoli was hit seven times by rifle fire while flying at 2500

feet, though neither the aircraft nor the pilot was disabled. One luckless

flyer had an engine failure behind enemy lines and was captured, though there

appears to be no record of his subsequent fate; with the reputation the Turks

had in those days it was probably grim.

Aerial bombardment

Although there appears to be no evidence that any of the

Flotilla’s pilots ever attempted to take aloft and use any form of firearm, the

concept of an offensive role for their aircraft was exemplified by the use of

aerial bombs. The first-ever bombing sortie was that undertaken on 1 November

1911 by Second Lieutenant Gavotti, when he dropped three 2kg Cipelli bombs on

the Taguira Oasis and a fourth bomb on Ain Zara. The relative success of

Gavotti’s sortie led to the use of modified Swedish Haasen hand grenades and

these were replaced by a small cylindrical bomb, containing explosive and lead

balls, designed by Lieutenant Bontempelli.

By February 1912, the Flotilla’s machines had been modified

to carry a large box (dubbed Campodonicos), each of which could hold ten

Bontempelli bombs, which could then be released, simply by the pilot pulling a

lever, in salvo or singly. The age of aerial bombardment had dawned. Nor was

this form of aerial warfare confined to daylight sorties. Later in the

campaign, on 2 May 1912, Captain Marengo, commander of a second air formation

which arrived at Benghazi in late November 1911, made a 30-minute night

reconnaissance as the first of several similar patrols. Then, on 11 June before

dawn, Marengo dropped several bombs on a Turkish encampment, inaugurating the

night bomber role.

During December 1911 and January 1912 the work of the

Flotilla was severely hampered by atrocious weather conditions, including high

winds and sudden storms. However, its aircraft continued to give direct

tactical support to the ground troops by scouting ahead of advancing columns

and locating enemy troops in the vicinity. Fresh aircraft for the Libyan airmen

began arriving in January, along with new pilots, including Lieutenant Oreste

Salomone, later to gain honours and national fame as a bomber pilot during

World War 1. By the end of January, due to the eastward movements of the

advancing Italian ground forces, it became necessary for the Libyan Flotilla to

change its base airfield, and a move was made to Homs on 12 February. From here

the aircraft flew in yet another new role: aerial propaganda. The pilots

scattered thousands of specially prepared leaflets far and wide amongst Arab

camps, with the result that large numbers of tribesmen were persuaded to become

allied to the Italian cause.

Revolutionary tactics

By this time the value of the aircraft was being fully

recognised by Italian Army commanders and the feats of the pilots were

acclaimed in official dispatches. The overall commander of Italy’s Air Battalion.

Lt Col di Montezemolo, arrived in Libya in February 1912 to inspect the Air

Flotilla and report on its activities and results. One item in his subsequent

report was the recommendation that Captain Piazza be repatriated to Italy, due

to the commander’s bouts of fever, and that he be succeeded by Captain

Scapparo. Piazza, once fit again, should be employed in organising flying

tuition.

The obvious success of the Libyan Air Flotilla soon led to a

second, though smaller flotilla being dispatched to Cyrenaica and based at

Benghazi. Once established, this formation’s first war sortie-a reconnaissance

patrol- was flown on 28 November by Second Lieutenant Lampugani. Though mainly

restricted to the areas close to Benghazi, this formation had its full share of

operational experiences. Most flights were met with fierce opposition from

Turkish ground fire, including anti-aircraft artillery. This latter novelty was

first experienced by Lieutenant Roberti on 15 December 1911 when flying over

some Turkish trenches; his aircraft and propeller received several shrapnel

strikes. As if to compliment the gunners on their accuracy, Roberti coolly

dived across the enemy battery positions and dropped some of his personal

visiting cards.

A terrible precedent

As recorded earlier, the commander of the Benghazi formation,

Captain Marengo, instituted a series of night bombing and reconnaissance

sorties between May and July. His only night-flying aid was an electric torch,

fixed to his flying helmet and operated by a normal hand- switch, in order to

read his few instrument dials. Tragically, it was a pilot of Marengo’s

formation who became the Italian Air Service’s first-ever wartime casualty. On

25 August 1912 at 0610 hours Second Lieutenant Pietro Manzini took off for a reconnaissance

patrol but almost immediately side-slipped into the sea and was killed.

With the end of the campaign, the Italian airmen won acclaim

from the international Press. One particularly prophetic war correspondent,

with the Turkish Army throughout the war, wrote, `this war has clearly shown

that air navigation provides a terrible means of destruction. These new weapons

are destined to revolutionise modem strategy and tactics. What I have witnessed

in Tripoli has convinced me that a great British air fleet must be created.’

Certainly, by their skill, imagination and courage, the Italian Air Flotillas

had inaugurated man’s latest form of destruction, pioneering most of the

military roles for the aeroplane.