The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 was a British single-engine tractor two-seat biplane designed and developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. Most production aircraft were constructed under contract by various private companies, both established aircraft manufacturers and firms that had not previously built aircraft. Around 3,500 were manufactured in all.

The B.E.2 has always been a subject of controversy, both at the time and in later historical assessment. From the B.E.2c variant on it had been carefully adapted to be “inherently stable”, this feature was considered helpful in its artillery observation and aerial photography duties: most of which were assigned to the pilot, who was able to fly without constant attention to his flight controls. In spite of a tendency to swing on take off and a reputation for spinning, the type had a relatively low accident rate. The stability of the type was however achieved at the expense of heavy controls, making rapid manoeuvring difficult. The observer, often not carried because of the B.E.’s poor payload, occupied the front seat, where he had a limited field of fire for his gun.

The Sikorsky Ilya Muromets (Sikorsky S-22, S-23, S-24, S-25, S-26 and S-27) were a class of Russian pre-World War I large four-engine commercial airliners and military heavy bombers used during World War I by the Russian Empire. The aircraft series was named after Ilya Muromets, a hero from Slavic mythology. The series was based on the Russky Vityaz or Le Grand, the world’s first four-engined aircraft, designed by Igor Sikorsky. The Ilya Muromets aircraft as it appeared in 1913 was a revolutionary design, intended for commercial service with its spacious fuselage incorporating a passenger saloon and washroom on board. During World War I, it became the first four-engine bomber to equip a dedicated strategic bombing unit. This heavy bomber was unrivaled in the early stages of the war, as the Central Powers had no aircraft capable enough to rival it until much later.

The Caproni Ca.3 was an Italian heavy bomber of World War I and the postwar era. It was the definitive version of the series of aircraft that began with the Caproni Ca.1 in 1914.

Apart from the Italian Army, original and licence-built examples were used by France (original Capronis were used in French CAP escadres, licence-built examples in CEP escadres). They were also used by the American Expeditionary Force. There has been some confusion regarding the use of the Ca3 by the British Royal Naval Air Service. The RNAS received six of the larger triplane Ca4s and did not operate the Ca3. The British Ca4s were not used operationally and were returned to Italy after the war. Some of the Ca.36Ms supplied after the war were still in service long enough to see action in Benito Mussolini’s first assaults on North Africa.

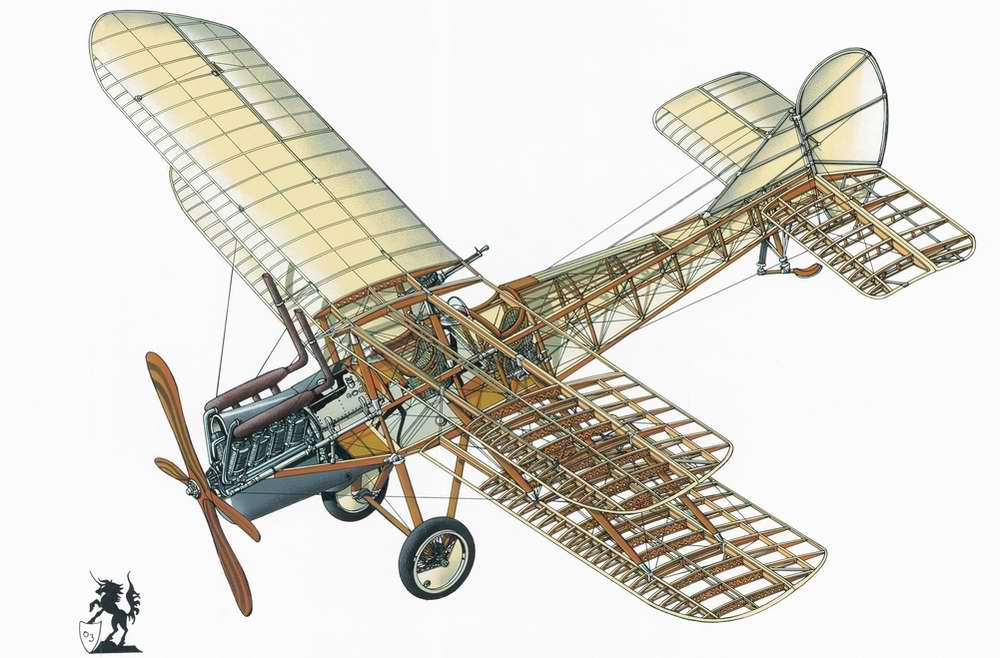

The Breguet 14 was a French biplane bomber and reconnaissance aircraft of the First World War. It was built in very large numbers and production continued for many years after the end of the war.

Apart from its widespread usage, the Breguet 14 is known for being the first mass-produced aircraft to use large amounts of metal, rather than wood, in its structure. This allowed the airframe to be lighter than a wooden airframe of the same strength, in turn making the aircraft relatively fast and agile for its size; in combat situations, it was able to outrun many of the contemporary fighters of the day. The Breguet 14’s strong construction allowed it to sustain considerable damage, in addition to being easy to handle and possessing favourable performance. The type has often been considered to have been one of the best aircraft of the war.

The first powered aircraft had been flown by the Wright

brothers only a decade before World War I began, but the airplane was soon to

play a major role. At first planes were only used for observation and

reconnaissance, and indeed they were able to provide an important new view of

the battlefield. At the Battle of Mons in southern Belgium on August 23, 1914,

British forces rushed to the rescue of the French as the Germans attacked them.

Just before the clash, the British sent out an observation plane to see what

was going on and discovered, to their surprise, that the Germans were trying to

surround them. The British high command immediately ordered a retreat, which

saved them from a disaster. A little later a French observation plane noticed

that the Germans had exposed their flanks, and the French attacked, stopping an

attempted drive to Paris. The value of the observation plane was soon evident.

It wasn’t long, however, before observation planes on

opposite sides began to come in contact. At first they merely fired at one

another with pistols and rifles, although at times they also tried to throw

rocks at one another’s propellers. One of the first pilots to escalate air

warfare was Roland Garros of France. Although most of the early airplanes used

in the war were “pushers,” like the Wright brothers’ craft, with the propeller

behind the pilot, it was soon discovered that the “tractor” design, with the

propeller in the front, was much more effective. The problem with this,

however, was that if machines gun were to be mounted so pilots could easily aim

and fire them, they would have to fire through the whirling blades of the

propeller, and this would quickly destroy the propeller blades. Garros decided

to protect the blades by adding steel deflectors to them.

In early April 1915 he tried out his new invention for the

first time. The recipients of his attacks were no doubt surprised when they saw

Garros’s airplane flying straight at them, shooting a stream of bullets. Garros

shot down four German airplanes using his new device, but on April 18 he was

forced down behind German lines. His airplane was seized, and the German high

command called in Anthony Fokker of the Fokker aircraft company and ordered him

to copy the device. Fokker saw, however, that it was seriously flawed: many of

the bullets hitting the blades were deflected, and some of them were being

deflected backward. Fokker and his team therefore began working on a system in

which the machine gun was synchronized with the propeller blade. A cam was

placed on the crankshaft of the airplane; when the propeller was in a position

where it might be hit by a bullet, the cam actuated a pushrod that stopped the

gun from firing. The new device was placed on German airplanes, and for many

months the Germans had a tremendous advantage in the air.6

In the meantime the British were also experimenting with the

mounting of a machine gun on an airplane. Aviator Louis Strange attached a

machine gun to the top of the upper wing of his plane so that the bullets would

clear the propeller. However, on May 10, 1915, his gun jammed. He stood up on

his seat in an attempt to pry it loose, but as he worked on it the plane

suddenly stalled and flipped over, then it began to spin downward. Strange was

flung out of the plane, but he managed to hang on to the gun on the upper wing.

For several moments he swung his legs around wildly, trying to get back in the

cockpit. Fortunately, he succeeded and was able to pull the plane out of its

dive just before it would have crashed.

Nevertheless, with the new Fokker design, the Germans

quickly achieved air superiority. Strangely, most of their new guns were

mounted on the Eindecker E1, a plane that was generally inferior to most

British aircraft. The casualties, however, were not as great as they were later

in the war because the British pilots stayed clear of the Eindecker. The morale

of the British, however, had been shaken, and they rushed to produce fighters

that could match the Eindeckers.

The era of the dogfight had begun. A dogfight was an aerial

battle between two or more aircraft. The Germans had an advantage when the

dogfights first began. As a result, they began knocking down British planes at

the rate of the about five to each of their losses. German aces such as Max

Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke became heroes at home as a result of the large

number of British planes they downed. Between them they shot down almost sixty

enemy aircraft before they were stopped. Finally, though, in the fall of 1915,

the British introduced two fighters, the F.E.2 and the DH2, which were a good

match for the German planes, and they also developed tracer ammunition that

helped. With it a pilot could see his stream of fire and adjust it if needed.

Pilots with eight kills became known as aces. At first, most

pilots went out alone, searching for enemy planes, but after 1917 squadrons

were introduced on both sides. The British developed squadrons of six planes

that usually flew in a V-shaped formation with a commander in the front. In

combat, however, they would break up into pairs, with one of the two planes

primarily on attack while the other was a defender. The German squadrons were

usually larger, and their groups eventually became known as circuses.

One of the leading British aces was Mick Mannock. He was a

leading developer of British air tactics, and between May 1917 and July 1918,

he shot down seventy-three German planes. Almost all pilots were under the age

of twenty-five, with many as young as eighteen. Many, in fact, were sent into

battle with as little as thirty hours of air training. So, as expected, their

life expectancy once they joined up was not long.

Dogfight tactics were well known, and everyone used them as

much as possible. The major tactic was diving toward another plane from above

when the sun was shining in the eyes of the opposing pilot. Both sides also

used clouds for cover as much as possible; they would attack, then head for the

clouds.

The best-known ace of the war was, no doubt, the German

Manfred von Richthofen, who was also known as the Red Baron. He was credited

with eighty combat victories during his career. As in the case of most aces,

however, many of them were against greenhorn pilots with only a few hours of

experience. He did, however, down one of the leading British aces, Major Lance

Hayden. During 1917 he was the leader of the German squadron called the Flying

Circus. The plane he piloted was painted red, both inside and out. His career

came to an end on April 21, 1913, when he was shot down by ground fire near the

Somme River.

On the Allied side, Billy Bishop was one of the most

celebrated aces; a Canadian, he was credited with seventy-two victories, and he

was instrumental in setting up the British air-training program. At one point

he fought against the Red Baron, but neither man gained a victory. He was

awarded the Victoria Cross in 1917. The best-known American ace was Eddie

Rickenbacker. Before he became a pilot he was a racecar driver, so flying a

fighter plane was a natural next step for him. When the United States entered

the war in 1917 Rickenbacker enlisted immediately and was soon flying over

Germany. On September 24, 1918, he was named commander of a squadron. In total,

he shot down twenty-six German aircraft. Another major American figure was

Billy Mitchell; by the end of World War I he commanded all American air combat

units.

Although the fighter planes got the most attention during

World War I, a much larger plane also played an important role. It was developed

to carry and release bombs over enemy territory. Strategic bombing was used

quite extensively during the war. Its object was to destroy factories, power

stations, dockyards, large installations of guns, and troop-supply lines. The

first bombing missions were by the Germans, who launched terror raids using

large Zeppelins (huge balloons) to bomb small villages and civilians as a way

to destroy the enemy’s morale. There were a total of twenty-three of these

raids over England, and at first there was little defense against them. But

quite quickly it became evident that they were easy targets, as most were

filled with flammable hydrogen and therefore easy to shoot down. So the airship

raids finally stopped, but Germany soon developed bomber airplanes. The British

also developed the Handley Page bomber in 1916, and in November of that year

they bombed several German installations and submarine bases. By 1918 they were

using four-engine bombers to attack industrial zones, with some of the bombs

weighing as much as 1,650 pounds. They developed a squadron that was able to

penetrate deep into Germany and hit important industrial targets. The Germans

retaliated, bombing both British and French cities, but in the end the British

dropped 660 tons of bombs on Germany—more than twice the amount the Germans

dropped on England.