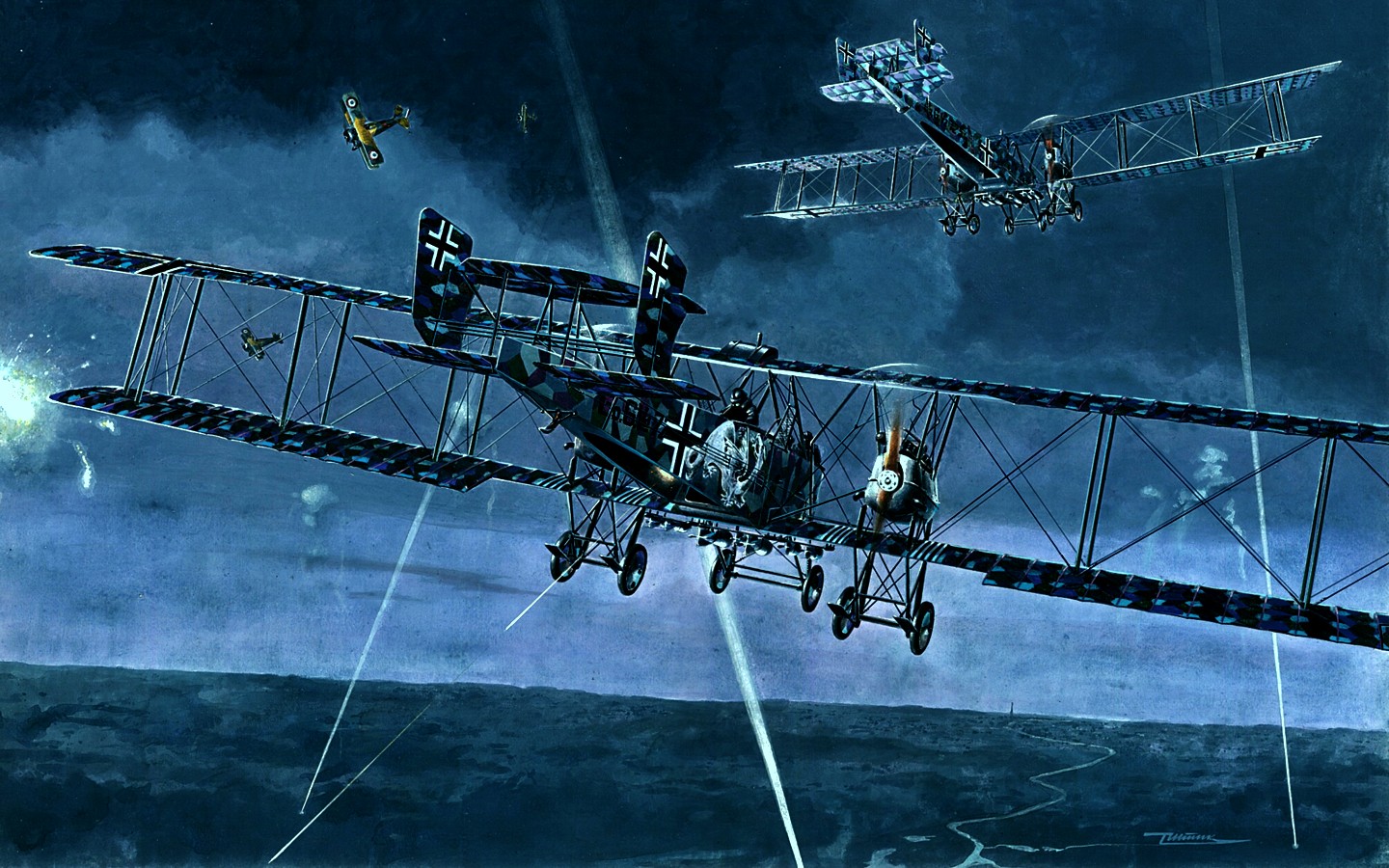

1918 Gotha G.Va – Taras Shtyk

1918 Fokker DVII Hermann Göring – Taras Shtyk

1918 Siemens Schuckert D.III Ernst Udet – Taras Shtyk

1918 Caproni Ca-42

Integral to the balance of intelligence advantage was air

superiority, which had never been more fiercely contested than in 1918. During

the war aircraft speeds and ceilings had doubled, engine horsepower quadrupled,

and bomb payloads grew even more. German aeroplane speeds had risen from 80 to

200 kilometres per hour, and maximum loads from 3.5 to 1,000 kilograms. Since

the development of fighters (or ‘pursuit’ aircraft as the Allies called them –

‘hunter aircraft’ or Jagdflugzeuge was the German term), combat had spread into

the skies. Aircraft took up roles that they would keep through the Second World

War and beyond: not just guiding the artillery but also striking ground targets

as a form of flying artillery themselves. They operated at sea and in every

theatre on land. They also embarked upon strategic bombing.

By 1918 ‘strategical’ bombing existed as a concept and was

discussed as such in the newly formed British Air Staff and Air Ministry. It

meant attacks on home-front targets such as cities, factories, and railways

rather than the enemy forces. Militarily the two sides’ efforts in good measure

cancelled each other out, but bomber raids on Paris and London hardened Allied

public opinion against Germany, and prompted reprisal raids, which if the war

had continued would have become much bigger. An escalation dynamic was in

evidence that anticipated later tragedies, although as yet the technology was

scarcely comparable to that which a generation later laid waste to Europe.

The first Hague Peace Conference in 1899 had banned the

dropping of projectiles from balloons but only for a five-year period, and

before 1914 the popular press and fiction writers had foreseen air attacks on

cities. London’s vulnerability caused a panic in 1913.83 After war began,

humanitarian considerations caused little hesitation. The French bombed

Ludwigshafen in 1914, and they and the British continued to raid enemy border

towns into 1915–16, although neither had yet developed specialized bomber

aircraft and the damage caused was slight. From Germany, only Zeppelin airships

could reach London, and they came under the German navy. Gradually Wilhelm –

who had scruples about targeting historic buildings and his cousins’ palaces,

while the Chancellor was worried about neutral public opinion – ceded to the

navy’s enthusiasm, and raids on London began on 31 May 1915. For some months

the British had no answer, but during 1916 new BE2C aircraft arrived that

climbed higher and were stable at night, and fired incendiary ‘Buckingham’

bullets. Supported by better anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, and an improved

ground observer system, they shot down so many Zeppelins that from September

1916 raids on London ceased. Because of raw-material shortages the airships’

skin was no longer rubberized, and their ribs consisted of wood rather than

aluminium, making them even more flammable. The danger seemed over, and in

early 1917 the British authorities were winding down their civil defence

arrangements.

But the Zeppelins prepared the way for bombing by aircraft.

German engineers had been working on the Gotha G-IV bomber since the start of

the war, and the OHL wanted it ready for raids to coincide with unrestricted

submarine warfare. London, 175 miles from the Gothas’ bases in Belgium, fell within

their 500-mile range. Unlike French cities, it could be approached over water,

without ground defences, and the Thames estuary provided a conspicuous

guideline. Gothas carried a smaller payload than did Zeppelins, but they were

faster (87 mph), higher (up to 10,500 feet), more heavily armed (carrying three

machine guns), and harder to shoot down. Moreover, whereas the British

decrypted the Zeppelins’ wireless code and always had warning of their arrival,

the first daylight Gotha raids (codenamed Operation Türkenkreuz) were

unanticipated. They killed and injured 290 people at Folkestone on 25 May, and

on 13 June they killed and injured 594 in bombing centred on London’s Liverpool

Street Station and the East End, including eighteen children at the Upper North

Street school in the East India Dock Road; on 7 July another raid on the

capital claimed 250 more casualties. By this stage there was media uproar and

tense discussion in the War Cabinet. Two fighter squadrons returned from the

Western Front (over Haig’s protests) – and a new agency, the London Air Defence

Area (LADA), was created under Major Edward B. Ashmore, a gunner moved from

Flanders. Ashmore added another barrier of fighters east of London and altered

their tactics so that they attacked the Gothas in groups rather than singly,

and the same bad weather that bedevilled British troops in Belgium assisted

him. In three raids during August the Gothas failed to reach London, and in the

last they lost three aircraft, one to AA fire and two to fighters. Perhaps

prematurely, they switched to night attacks.

Night bomber attacks were the last and most challenging of

the threats against London during the war. Now the Gothas were joined by

Riesenflugzeuge or ‘Giants’, with a 138-foot wingspan (that of a B-29 Superfortress

in the Second World War), a maximum height of 19,000 feet, nine crew wearing

heated flying suits, six machine guns, and a payload of up to 2 tons, including

1,000-kilogram bombs that could wreck a housing block. They could take enormous

punishment, and none were ever shot down. During ‘the blitz of the harvest

moon’ between 24 September and 1 October 1917 night-flying bombers visited

London six times. For the British this was the most trying time: their

anti-aircraft batteries were nearing exhaustion due to ammunition expenditure

and deterioration of the barrels, 100,000–300,000 people took shelter in the

Underground each evening, and up to one sixth of munitions production was lost,

although contemporary estimates ran much higher. Worsening weather and wear and

tear on the bombers and their crews then provided relief, and during the winter

Ashmore installed better searchlights and balloon barrages while the Sopwith

Camel proved itself as an effective night fighter. As in the campaign against the

U-boats, there was no one spectacular turning point but gradually the defenders

inflicted greater losses and the attackers caused less damage. From October the

British read German wireless messages, and once given more warning their

aircraft destroyed an average of one tenth of the Gothas on each raid. Terrible

episodes still took place, such as the bombing of a basement shelter in Long

Acre on 28 January, with over a hundred killed and wounded. But in the biggest

raid of all, on 19 May 1918, forty-three aircraft took off but six were lost in

action and seven in accidents, while according to a survey by the medical

journal The Lancet the civilian mood had now improved. From this point raids on

London (though not the provinces) ended, in part to redirect the bombers to the

Western Front. In addition the campaign was taking a growing toll of aircraft,

a total of twenty-four being lost in action and another thirty-seven in

accidents. Partly because of raw-material shortages the Gothas were shoddily

made, and their undercarriage was liable to collapse on landing. By 1918,

moreover, British fighters could be mobilized much faster and Ashmore

established an operations control room where observers’ reports were

centralized and instructions coordinated in a manner prefiguring the second and

more celebrated Battle of Britain.

A parallel Gotha campaign against Paris began on 30–31

January 1918, leaflets dropped over the trenches justifying it on the grounds

that the French had refused peace. By 15 September a total of fourteen raids

had dropped 664 bombs, although the heaviest attacks came in the spring,

seventy people dying on 11 March in a panic crush at the Bolivar Métro station.

As against London, the Germans launched a multi-faceted attack on the city’s

morale, as the Gotha raids preceded the ‘Michael’ offensive and on 22 March the

first shell landed from the ‘Paris gun’, the precursor to 370 more between 23

March and 8 August. In fact the gun caused greater shock than the Gothas, which

dropped 30 tons of bombs compared with 100 tons on Britain. Fighters played a

smaller role in air defence than in London, partly owing to a shortage of

planes, so anti-aircraft guns were the main – and quite effective – defensive

implement. Even though Paris was only two hours’ flying time from the enemy

trenches, few of the bombers reached their destination and most got lost or

turned back. Only eleven of the thirty Gothas that departed on 30 January

arrived, and of 483 sent in total thirteen were shot down and only thirty-seven

got through to the city.

Total casualties in Paris from air raids were 266 killed and

603 wounded (the Paris gun killing a further 256 and wounding sixty-two), while

British casualties in the Gotha and Giant raids numbered 856 dead and 1,965

wounded, and the property damage was estimated at £1.5m. Ashmore later compared

these figures to the more than 700 lives lost annually in London in the 1920s

on the roads. Certainly they were small in comparison with the thousands dying

daily on the Western Front, and the Germans could have pursued the campaign

more ruthlessly. By August 1918 they had ready a new device based on magnesium

and aluminium, the Elektron Bomb, which was incendiary enough to set off

firestorms. After delays due to bad weather, a raid on London was planned for

23 September. But at the last moment Ludendorff called it off, because the

German government feared reprisals, but perhaps also because he was already

contemplating the ceasefire appeal that he demanded five days later.

Humanitarian sentiment, however, formed no particular constraint. When in 1917

Bethmann Hollweg complained that Gotha bombing was ‘irritating the chauvinistic

and fanatical instincts of the English nation without cause’, Hindenburg

replied that being conciliatory would gain nothing and the raids kept war

material away from the Western Front: ‘It is regrettable, but inevitable, that

they cause the loss of innocent lives as well.’ More important as a limiting

factor were technical considerations. A Giant cost over half a million marks

and each one needed a fifty-man ground crew: only eighteen were built. Even the

cost of a Gotha doubled between 1916 and 1917. Although supposedly aircraft

were second only to submarines in their claims on manufacturing resources,

Germany lacked the manpower and raw materials to fulfil its construction

programmes, and strategic bombing competed with the needs of army support. In

addition the prevalent cloudy weather over North-Western Europe hindered all

kinds of air activity (as over Kosovo as late as 1999), but especially bombing:

which meant sustained attacks as in September 1917 were rare. And in comparison

with their Second World War successors, 1918 bombers carried tiny payloads and

delivered them inaccurately, not least because bombsights were still under

development. The Gothas attacking London operated at the limit of their range,

under fire, and mostly at night, and achieved little beyond random terror. They

hardly damaged docks and railways or the armaments industry, even the enormous

complex at Woolwich Arsenal being hit just once. Hence the main practical

consequence was to tie up Allied resources in air defence, which Hindenburg and

the commanding general of the German air force, Ernest von Hoeppner, recognized

as an objective. At least in this respect they had considerable success.

Britain lost forty-five aircraft and seventy-eight aircrew in the battles over

its home islands, all the latter in accidents, whereas German casualties were

several times heavier. But while in 1917–18 Germany committed approximately 100

Gothas, 15 Giants, and 30 Zeppelins to the British campaign, Britain committed

some 200 aircraft to its defence, supported by searchlights and by

anti-aircraft guns crewed by 14,000 ground personnel.

Nor was this the end of the reckoning, as the Gotha raids

caused a redirection in British air policy, which otherwise would not have

happened at this time, nor met so little resistance. After the Liverpool Street

bombing, the Cabinet decided almost to double the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) from

108 to 200 squadrons, with most of the extra aeroplanes being equipped for

bombing. Although this target was never reached, production rates rose

substantially. Jan-Christian Smuts, the South African general and former

defence minister who had joined Lloyd George’s War Cabinet, reported to it on 9

August that ‘the day may not be far off when aerial operations with their

devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial centres and population

centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war, to which

the older forms of military operations may become secondary and subordinate’.

He recommended merging the RFC with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), under

an Air Ministry with its own air staff to plan for the employment of an aircraft

surplus that the Ministry of Munitions – overconfidently – expected. Motivated

partly by reports that Germany planned a huge bomber expansion, the government

approved Smuts’s recommendations and passed legislation to create the Air

Ministry in January 1918, the merger into the new RAF following in April.

Finally, in the wake of the ‘harvest moon’ raids, the Cabinet authorized

immediate reprisals. The climax of the German raids on London and Paris was

followed by the climax of the Allied air assault on the Rhineland.

The 1918 strategic air offensive against Germany was

predominantly British. The Americans took part, using British DH9 bombers, and

suffered heavily, but the French high command was ambivalent, partly because it

feared retaliation and partly because it believed that bombs were better

employed against the German army and its staging areas. The French had

developed the fast and high-flying Bréguet XIV B.2 two-seater bomber, which

could be escorted over Germany by a long-distance heavy fighter, the Caudron

R.XI. During 1918 they fought a battle of attrition: in the first quarter they

dropped 200 tons of bombs and lost 20 aircraft; in the second they dropped 500

tons but lost 50 and the authorities hesitated over whether to continue; but in

the third quarter they dropped 700 tons and lost 29 and in October they dropped

600 tons and lost 3. They were slowly winning mastery of the German skies. As

for the British, from October 1917 their 41st wing carried out day and night

attacks on Germany from Ochey in Lorraine. In June 1918, the Independent Force,

RAF (or IF) was created, under the command of Sir Hugh Trenchard, previously

commander of the RFC. Now the raids were intensified and their radius

lengthened. According to Sir Frederick Sykes, the Chief of the Air Staff, ‘as

the offensive is the dominant factor in war, so is the Strategic Air Offensive

the dominant factor in air power’, and the offensive would aim to dislocate the

enemy munitions industries, attack the U-boats in their bases, and ‘bring about

far-reaching moral and political effects in Germany’. Between October 1917 and

November 1918, 508 raids took place, dropping 14,911 high-explosive bombs and

816,019 incendiaries. In July and August the British went to the limits of

their range, bombing Cologne, Frankfurt, Mannheim, and Darmstadt. The Air Staff

priority for 1919 was the Ruhr’s steel and chemical industries, and the new

Handley Page V/500 bomber, becoming available in November 1918, could reach

Berlin.

Yet if anything the Allies’ raids were less destructive than

Germany’s. German casualties from air raids during the war totalled 746 killed

and 1,843 injured: the damage was valued at 24 million marks (£1.2m), but

industrial disruption was slight. Sykes cited photographic evidence of damage to

factories and German press reports that the Rhinelanders were demanding more

protection, but a post-war RAF investigation was more sceptical. Although

alerts and sleepless nights disheartened the workforce, few blast furnaces were

damaged and the huge BASF chemical works at Ludwigshafen, a major target, never

had to shut down. Similarly the French tried to halt supplies from the Briey

iron ore mines in Lorraine, a location close to their border that produced 80

per cent of Germany’s output, but their efforts were completely ineffective.

Three main explanations can be cited, the first being

technical. By late 1944 Britain and America were dropping 90,000 tons of bombs

on Germany per month in 18,000 sorties, as a result of which the Third Reich’s

armaments output finally began to decline: between October 1917 and November

1918 the British dropped 665 tons in total, and less accurately. Similarly an

Allied campaign in June–July 1918 dropped 61 tons of bombs over the Germans’

railways but demonstrated that bombs could not destroy trains unless landing

within a few feet of them. Germany’s fruitless efforts in June to smash the

Allies’ crucial railway viaduct at Etaples pointed to the same conclusion.

Moreover, the Allied bombers had just five and a half hours’ endurance, so only

Germany’s south-western corner was in reach. The weather was another obstacle,

the campaign winding down as the autumn skies became more clouded. And although

the British DH4 bomber was a dependable workhorse, the new DH9 proved constantly

unreliable and many missions were abandoned because of engine failure.

The second explanation was the Germans’ countermeasures. In

1916 they introduced a centralized observation system and unified fighter

defence, later supplemented by searchlights, anti-aircraft guns, and balloons.

In summer 1918 they reinforced their fighters to 320; and British losses became

formidable: 104 day bombers and thirty-four night ones were lost to German

action and 320 crashed behind Allied lines, while in September the IF lost 75

per cent of its aircraft in one month. By the end of the war air defence, like

the rest of German aviation, was being slowly paralysed by shortages, but until

then it exacted a high price.

The third and final impediment came from the Allies’ own

priorities and policies. Foch shared the general French lack of enthusiasm,

stating in a 1 April directive that ground attacks against the enemy troops

should be the main objective (and air fighting only as necessary to achieve it)

alongside bombing of key railway junctions. He wanted the IF under his

authority. In October the British agreed to an inter-Allied bombing force under

Trenchard that would be answerable to the Marshal, and this body would have

overseen strategic bombing in 1919. But Trenchard himself never carried out

operations as the air staff had intended, and like the French he was a

strategic bombing sceptic who as RFC commander had seen his primary duty as

assisting the army. Although Sykes instructed the Independent Force to

‘obliterate’ first the German chemical industry and then the Lorraine steel

industry, in fact of 416 raids between June and September 1918 only thirty-four

were against chemical plants and another thirty-four against steel plants,

whereas 185 were against rail targets and 139 against aerodromes, objectives

that Trenchard had been told to leave for other parts of the RAF. Even the

locations on which effort was concentrated escaped critical damage: the

‘railway triangle’ round Metz and Sablon was the most heavily attacked single

target, but traffic there was never halted for long. It was also true that

Trenchard never received a force commensurate with the government’s initial

intentions, as although the IF grew from five to nine squadrons he had been

required to plan for thirty-four. Only 427 of the 1,817 bombing aircraft sent

from Britain to France in 1918 went to the IF, and at the armistice only 140 of

the 1,799 RAF aircraft on the Western Front were assigned to it. Various

reasons lay behind this, notably that the expected production surplus did not

materialize and losses during the Ludendorff offensives were heavy. But even a

much larger Independent Force would have achieved little, and airpower’s most

important function remained direct support of the armies.