By the middle of April 1945, Marshal Koniev’s First

Ukrainian Front had penetrated deep into the eastern half of Czechoslovakia,

while Patton’s Third Army had advanced into the western areas. This prompted

calls from the Czechoslovak government for the immediate transfer of the army

units to the western sectors in order to participate in the imminent

liberation. Nichols, writing to Eden, relayed and endorsed proposals from Hubert

Ripka that such a transfer be made together with a token force of air force

pilots and their machines from Britain. Ripka had suggested that the effect on

morale ‘would be out of all proportion to the actual number of airmen

concerned’. There had obviously been no response because a week later, on 25

April, Ripka wrote to Nichols and again called for the ‘immediate despatch’ of

all possible army and air force units to the fighting front in western

Czechoslovakia, insisting that such a move was ‘essential for home morale’.

In what by then seems to have been its customary practice,

the Air Ministry lingered a while before replying. In fact, it waited until the

war was almost over in Europe before the matter was taken up by Beaumont at the

DAFL. He had been approached in late April by Janoušek, who had urged the

immediate transfer of at least the three fighter squadrons, minus their British

personnel, to the liberated territories. To save any fuss about demobilisation,

the units could move as a detachment of the RAF and then, when the war was

over, a new Anglo-Czechoslovak Agreement could be negotiated. Writing on 5 May

1945 to AM William Dickson, then Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Policy), he

suggested that the transfer could take place reasonably effectively if they had

a three-month pack-up of spares to be going on with; and, perhaps as his trump

card, he let it be known that the Foreign Office approved. But he also noted

that ‘there may be complications with the Russians with regard to the

employment of these squadrons in Czechoslovakia’. This was a mistake, for if he

really wanted to get anywhere with the plan, it would have been wise to keep

the Russian factor at the lowest possible profile. As it was, he had let the

genie out of the bottle.

Dickson rejected the plan at once. His leading point was

that ‘we can hardly be a party to the despatch of this Czech force into an area

which is under Russian military occupation without having an assurance that the

Russians approve’, and he also pointed out for good measure that they would

have to fly through American air space, so they would need to concur as well.

He then took pains to distance himself from the apparent goodwill of the

Foreign Office, telling Beaumont rather curtly to busy himself with RAF matters

concerning the squadrons, and to let Janoušek know that when he had the

agreement of the Russians, his men could go home. Reasonably enough, the Air

Ministry was prepared to wait for the Foreign Office to give the go-ahead to

the plan, but of particular importance here is the insistence that it should be

the responsibility of the Beneš government to provide evidence of Soviet

concurrence, and it was this condition which became the keynote of almost

everything which followed.

The situation in Prague was complex. Beneš and his

government were already there, having made the journey via the Soviet Union and

through the newly liberated territories in the east. He had left Janoušek and a

handful of other officers in Britain to supervise demobilisation and repatriation.

Fearful of another scenario similar to the one which had paralysed Poland at

the war’s end, he was determined to minimise Russian influences at all costs,

except for provoking a coup. There were powerful communist elements in

Czechoslovakia from the military and political wings, and his position was

always delicately balanced between having enormous numbers of Red Army troops

on his soil and a natural desire of the people to see their men in the fighting

forces come home to a hero’s welcome.

Prague was officially a Soviet zone; the Americans had

agreed to that, and the British had agreed with the Americans. In the eyes of

the Foreign Office, this meant that the matter was virtually removed from

British hands in so far as executive decisions were concerned. All that needed

to be done was: (a) secure Russian approval for the repatriation; (b) let the

Americans know; (c) let them work the logistics out between themselves. All the

British had to do was wave goodbye at the appropriate moment. This, at any

rate, was the plan, and everything now rested upon the Soviet attitude. Letters

to that effect were issued swiftly. Alec Randall in the Foreign Office informed

Hubert Ripka that the RAF would give the green light as soon as the Russians

signalled their consent.

But Ripka was not happy with that at all. The request for

the transfer, he said, had come directly from President Beneš in Prague, and

since the President would not dream of acting against his government’s

interests while still in the Soviet zone of occupation, the latter’s approval

could therefore be taken for granted. The Foreign Office reacted positively to

this. A meeting took place on 17 May, when this argument was thrashed out with

the DAFL, and all seemed content that Ripka’s assessment of the situation in

Prague was sound enough. British caution prevailed, however, and it was felt

prudent to be absolutely clear that the Russians would not object. Philip

Nicols, due to leave for Prague as the British ambassador, was told that the

Beneš government should obtain Moscow’s ‘formal agreement’. This meant their

agreement in writing, and this also proved to be another mistake. For if the

British government had been sufficiently assertive and simply sent the

Czechoslovaks home, much of what followed might never have happened.

Even the hitherto sceptical figure of Dickson aligned

himself with the view that the Russians had approved the transfer by virtue of

their silence. Indeed, he was positively sanguine. He thought the three-month

detachment plan to be a good one too, allowing the British to maintain

influence over the Czechoslovak Air Force while at the same time providing a

useful firewall against any accusations that the British were supplying a

foreign power in the heart of Eastern Europe; after all, as a detachment the

Czechs would still be a part of the RAF. Embracing the political dimension, he

added:

Moreover, I suggest that there is nothing that the

Russians want more than for us to be difficult in helping the Czechs. The

former are offering equipment to the Czech Army with both hands, and they will

be delighted at anything which will tend to make the Czechs turn more and more

to them for help. The Czechs do not want to divorce themselves from the RAF at

this stage and have asked for three months grace in which to consider the

return to Czechoslovakia all of their units, [though] they are most anxious for

the fighter squadrons to return and remain there while deliberations are

proceeding.

The irony in this last sentence is exquisite: after five

long years of struggling for independence, convenience (and perhaps political

expediency) had forced a change of heart, and now the last thing the

Czechoslovaks wanted was to be separated from the RAF.

This was the position on 25 May, approximately five weeks

after Ripka’s initial request for the return of the squadrons. And yet deep in

Whitehall, some minds remained uneasy about the lack of definite Soviet

approval. A week went by, and perhaps there was much finger-tapping and

pencil-chewing in the Foreign Office because by the end of May doubts were

beginning to surface. The focus was not so much upon whether or not the

Russians agreed to the transfer, but under what circumstances the fighter squadrons

were to return. If, for example, they returned with RAF markings on the planes,

would that arouse Soviet suspicions that the British were emphasising their

relationship with the Czechs? But if they returned with Czech markings, would

that give the Soviets a chance to treat the contingent as fair game? As Jack

Ward noted in a long minute on the subject: ‘I believe that the Russians have

already collared the Czech Army, but that we still have a chance for the air

force.’ Such doubts were enough to force a retreat to the original position.

The Russians must give their absolute and unconditional approval before a

single kitbag was packed.

Meanwhile, six hundred miles or so to the east, the

frustration was increasing. Men within the Beneš government thought the British

were deliberately stalling to force the hand of the Soviets, and in a broadcast

from Prague in early June, Beneš had raised the stakes by promising his airmen

that they would be home soon. In England too, the levels at which the problem

was being discussed were also raised. The Chiefs of Staff Committee drafted a

report for Churchill on 7 June with a brief synopsis of the problem, placing

emphasis upon the fact that an immediate postwar association with the air force

would provide ‘a valuable connecting link with the Czechoslovak Government’.

Churchill had recently issued his ‘standstill’ order regarding Royal Air Force

strength in Europe, meaning that there must be no immediate depletion of

numbers, hence the Committee’s decision to refer this matter to him. After

declaring that 311 Liberator Squadron was no longer required as a service unit,

and that the three fighter squadrons were ‘efficient fighter and ground attack

units’, the Committee decided that ‘the loss to our fighting strength will not

be appreciable’ if they returned in the near future. On the same day, the Air

Staff issued a note for general circulation to all relevant departments within

the Air Ministry supporting the proposals, and although both bodies still

emphasised the need for Russian concurrence, it was accepted that a postwar

agreement with the Czechoslovaks could be politically useful ‘at a time when

they will be in many respects under the dominating influence of the USSR’.

Finally, again on the 7th, Nichols sent a despatch for Cabinet distribution

which reviewed the military situation in Prague. Marshal Koniev had received

the Freedom of the City, and again Beneš had called for the swift return of his

air force. On the 8th, the Air Staff drafted an annex to the Committee’s report

recommending the transfer; and on the 11th, the COS report, together with the

Air Staff annex, was sent to Churchill. On the 13th he wrote above the

document: ‘Let them go back forthwith.’

Once the great man had spoken, the ball was now in play. On

the same day, Dickson issued a general directive stating that the Prime

Minister and the Chiefs of Staff had decided that the four squadrons were to

return at once, and therefore all the relevant directorates should prepare. The

detachment scheme would still apply, ‘but the Russians will not be told for the

present. To them, the move will appear as the permanent return of the

Czechoslovak Air Force to Czechoslovakia.’ As always, the parcel was tied with

the now familiar ribbon, ‘everything subject to Russian agreement’.

We might pause at this moment and consider the final couplet

of this directive. On the one hand, the Soviets were to be deceived; on the

other, they were expected to give their consent to this deception, albeit

unknowingly. Having lost its value as a military arm, the Czechoslovak Air

Force had now completed its transformation into a political tool once again.

The British were not remotely interested in whether or not the contingent would

be a viable force in its homeland, because the opportunity to claim a stake in

a Central European country presently occupied by the armies of the Soviet Union

was now of far greater importance. Furthermore, ‘Russian agreement’ was rapidly

becoming something of a diplomatic unicorn – sought by many, seen by none. No

evidence has come to light during this study which proves conclusively that the

Soviets made any pronouncement on the subject, negative or otherwise, and all

the contemporary evidence, circumstantial though it is, indicates that what little

interest they had in the matter was generally positive.

Oddly enough, when something which approached consent did

finally appear, the British refused to believe it. On 13 June, Seligman wrote

to Christopher Warner and told him of a letter, apparently received by the US

5th Army in Plzeň, which stated that the new Red Army commander in Prague –

named as Major-General Paramzik – had confirmed that the Czechoslovak

government now had ‘full and unrestricted access’ to Prague airport. An

extract, over Paramzik’s name, found its way on to Seligman’s desk:

Will you please inform the Allied Supreme Council that

the High Command of the Red Army have ordered that British aircraft carrying

military or civilian persons may fly without restriction and are to land at

Ruzýn aerodrome near Prague. The aircraft so landing are guaranteed an

unrestricted return flight.

When Janoušek heard of this, he claimed that it gave carte

blanche to the Czechoslovak Air Force to return immediately. Seligman

commented: ‘He was quite emphatic about this, but we do not altogether share

the view, although it is true to say that this is the first occasion on which

we have seen anything resembling a permit of any sort from the Russians for

Czechoslovak personnel to land in their own country.’ Warner then transmitted a

message to Nichols in Prague:

Authority has now been received for transfer of Czech air

squadrons to Czechoslovakia with their aircraft as soon as satisfactory

evidence is received that Russians agree. Air Marshal Janoušek has endeavoured

to convince the Air Ministry that they have already done so, but the letter

from the Major-General of Red Army Prague Command . . . which he produced as

evidence, appeared to the Air Ministry clearly to refer to flights of courier

aircraft since it referred to return flights from Czechoslovakia as well as

flights in.

One might be forgiven for thinking that this was taking

caution to excess. All parties well knew that the move could never have been

accomplished in one straight hop from Britain to Czechoslovakia, and that a

substantial degree of ferrying of stores, effects and personnel – civilian and

military – would be involved. Even the most critical reading of Paramzik’s

‘permit’ forces the conclusion that all these aspects had been covered, and

perhaps the only food for pedants lies in the phrase ‘British aircraft’, which

could be interpreted as aircraft manufactured in Britain or aircraft with

British markings – a distinction which would have affected the proposal to

livery the planes in Czechoslovak colours and symbols. Nevertheless, this was

not the point which Warner focused upon, and in closing he informed Nichols

that a three-month pack-up of spares would be supplied:

It must, of course, be obvious both to the Russians and

the Czechs that the former will be able to reduce the squadrons to impotence,

if they so desire, by refusing them aviation spirit and by declining to agree

to their being supplied from here with the major replacements which will

gradually become necessary. The Air Ministry calculate, however, that even in

this event the air squadrons should be able to do an adequate amount of flying

for a period of about three months to have a good propaganda effect.

It is possible to defend the rather cynical position adopted

here by the Air Ministry, given the huge problems that were developing in

Poland at the time, but the way they were going about it handed all the winning

cards to the Russians who, when all is said and done, hardly had anything to do

with the situation at all.

But Karel Janoušek cared nothing for the politics just then.

As far as he was concerned, he and his men could go home at last after more

than six years in exile. Emboldened by the prospect, he asked that all three

fighter squadrons be completely re-equipped with brand new Spitfire IX HF(E)

aircraft so that they might not have to participate in the victory parade in

tired machines. This, thought the Air Ministry, was a good idea. Almost at

once, however, it was pointed out that this might offend the Russians, since

they had been denied these very planes at a late stage in the war, and it took

another couple of weeks before a compromise was reached – one full squadron

would be so refitted and the others given a thorough makeover. In the event, it

was at last decided that all the squadrons should receive new machines, but

over a staggered period finishing in early August 1945.

Amid all this confusion, politics surfaced again. Nichols

had been busy in Prague still trying to secure cast-iron Soviet consent. He had

then been told that all Red Army units were scheduled for withdrawal during the

first two weeks of July, and that Beneš and his ministers ‘were loth to

approach the Russians for they did not consider the latter to have any

authority in the matter’. One purpose of his note was to ask if this withdrawal

obviated the need for Soviet approval anyway, although he had heard that a

request was shortly to be made to Marshal Koniev for his forces to supply

aviation spirit once the squadrons returned. Surely, it was argued, Russian

agreement would be implicit if the answer was positive. The Czechs themselves

also insisted that the military command in Prague was ‘wholly Czechoslovak’,

and the delay was making matters worse, not better, in their relations with the

Soviets. At last, on 18 July, Dickson gave the ‘go’ order. On 7 August, all

three fighter squadrons would return to Prague in mixed livery, the crew all

wearing RAF uniform, with prominence given to their own national ranks and

service badges. As it happened, a one-week delay was caused by bad weather, but

at 2 p.m. on Monday 13 August 1945, all 54 Spitfires landed at Ruzýn airport in

blazing sunshine, having twice flown low over the city in close formation.

The squadrons were reviewed prior to departure by AM Sir

John Slessor on 3 August. In a speech originally drafted for Portal, he paid a

handsome tribute to the officers and men of this gallant little force and made

useful references to a desire for postwar collaboration and friendship. After

they had gone home, a week-long party got under way, during which everybody who

mattered mounted the podium and recited glowing tributes and heartfelt thanks

to the RAF and all it had done to keep the nation’s hopes alive during the

years of occupation. Present throughout this week of celebration (in which, it

is said, the pubs ran dry of beer, leading some hotels to import emergency

supplies from southern Germany) were an outstanding array of Royal Air Force

commanders, many of whom received the Order of the White Lion from the hands of

the President. Nichols returned a detailed report of this event also, drawing

Ernest Bevin’s attention to the valuable opportunities afforded for high-level

discussions between British and Czechoslovak officers. As far as the Ambassador

was concerned, this did much ‘to serve the interests of His Majesty’s

Government’, and the jolly atmosphere ‘demonstrated that the mutual respect and

good fellowship established under war conditions . . . are still potent factors

in the relations between the two countries’.

So it had all ended in handshakes, backslaps, medals and

smiles all round. In that last week of August 1945, the Czechoslovak Air Force

was the nearest it ever came to being a true ally, at least in British eyes and

those of the Czechoslovak press. All the quibbles and niggles of five long

years of war were put aside or forgotten amid the swirl of parties and

speeches, but as we shall see, the bonhomie was not to last long. The seeds of

disaster had already been sown and were starting to germinate. The British, by

constantly seeking Soviet approval, had given time for powerful anti-Western

blocs to develop inside the Czechoslovak military, although it should have been

perfectly easy to understand why Beneš did not want to go cap in hand to the

Soviets and ask their permission for his air force to return to its homeland.

Such an action would have been contrary to his hunger for prestige and all his

beliefs about the sovereignty of his country. The British had fooled themselves

into believing that the Russians cared about what this tiny country did or did

not do with its equally tiny air force, and by concentrating on that instead of

supporting their ally to every last degree, they came away with nothing.

Things began to go sour early in September. The British had

confidently expected negotiations towards an new air agreement to begin as soon

as things began to settle down in Czechoslovakia, but then came sudden news of

a major upheaval in the organisation of the Czechoslovak Air Force itself. The

new Director of the DAFL, Air Cdre Ferdinand West, informed the Foreign Office

that Janoušek had been removed as C-in-C and replaced by Slezák, who had now

been openly proclaiming his communist sympathies:

It seems that the Headquarters of the Czechoslovak Air

Force in Prague has been almost entirely re-staffed. Those Czech officers of

high rank who held appointments in the RAFVR have been dispersed and, in nearly

every case, are filling relatively unimportant posts.

So the wheel had turned full circle, and the man who had

deposed the hated Slezák in 1940 now found himself pushed aside in favour of

him. West continued:

I gather this internal trouble is largely political and

Janoušek has been accused of being too Anglophile in his tendencies and not

sufficiently appreciative of the Russians. Extreme leftists have even labelled

him as a Fascist and anti-Jew leader.

Another telegram, this time from Nichols, told London that

‘the Russians are displeased that most personalities holding executive positions

in other ministries are those with wartime experience in England and who

possess no undue communist tendencies’. Beneš was already losing control of his

armed forces, and now we may glimpse the Soviet strategy regarding the return

of the squadrons in August, for it would have been counter-productive to place

any obstacles in the way of the transfer when the overall aim was to get the

men home and then begin the process of discarding the ‘dangerous’ elements. The

delay merely enabled them to strengthen their power base throughout the summer.

London was shaken by this news, but by no means was all hope

lost. It now became absolutely vital to secure a re-equipment deal with Prague

before the Soviets completed the process of absorption. The omens looked favourable.

No one had raised any objections to the supply and maintenance of the squadrons

under the detachment plan, and senior pro-communists within the Czechoslovak

Ministry of Defence had let it be known that sixty Spitfires might be the first

item in a substantial order to follow soon. The focus now shifted to the

organisation of a full expedition with the authority to negotiate on behalf of

the Czechoslovak government. Janoušek had been sent from Prague to wind up the

Inspectorate in London, but he dropped by at the Foreign Office and led it to

believe that he would head the Mission when it came. In return, London told

Prague to bait the hook with a promise of assistance ‘on a generous scale’ if

the Mission arrived with full negotiating powers. Nichols returned with a firm

date, 9 December, when a team of senior air force officers would arrive with a

long list of requirements and plenty of money to spend.

What followed then was a series of postponements. Christmas

came and went, and what few communications there were hinted that the Russians

were also preparing a list of their own. The promise of a ‘substantial gift’ of

equipment to the Czechoslovak Air Force from Moscow chilled British hearts, but

then out of the blue a new date for the Mission was floated: 6 February 1946.

More to the point, the Czechoslovaks had requested another pack-up of spares to

maintain the existing Spitfire squadrons, but as a minute stated: ‘we cannot go

on indefinitely sending supplies until the policy and financial aspects of the

matter are settled’. Within days, however, another postponement had been

called.

By late February, a sense of urgency was creeping into the

despatches – not panic exactly, but something close to it, as it became

apparent to all that the last chance of holding on to a position of influence

was sliding away. The Air Attaché in Prague, Gp Capt G.M. Wyatt, was informed

that preparations were nearly complete, yet he should not delay any longer,

‘but approach the Czechs in the strongest possible terms and press them to send

an Air Mission’. As more bait, the Air Ministry suggested that he tell it at

once that any discussions now would not commit it to a final decision, and to

perhaps hint that growing shortages of materials meant that action sooner

rather than later might be in their favour.

Wyatt replied quickly, having consulted Nichols, and both

were agreed that there was ‘practically no chance of persuading the

Czechoslovak Government to discuss future equipment’ at that time. The reason

given was that the impending elections in Czechoslovakia made it likely that

the government would not ‘risk discussions on this subject with us until

Russian intentions are clearer’. Within five days, however, Wyatt telegraphed

again and told London that a Mission would be despatched soon, but Janoušek ‘frankly

disliked the idea of heading a Mission whose function was to sever rather than

enhance connections with the RAF’.

After yet another short postponement, the Czechoslovak Air

Mission finally arrived in Britain and convened on 3 April 1946. Janoušek was its

leader, but Slézak was not among the team. Swiftly discussed was the supply of

72 Spitfires, 24 Mosquitoes, 4 training aircraft and enough bombs, ammunition

and auxiliary equipment to sustain ten days of fully mobilised combat, all at

the knock-down price of £354,000. This the Mission accepted with thanks. Then,

amid many fine speeches, the sad duty of the Committee was to formally end the

Anglo-Czechoslovak military association which had begun in the awesome chaos of

the summer of 1940. It was agreed by all parties that on 30 June 1946 the

Czechoslovak Section (RAFVR) would cease to exist as a legal and political

entity, and the supporting agreement would be terminated. All that remained to

be done was for the Czechoslovak government to ratify the re-equipment plan and

then a new relationship could begin.

Janoušek and his team returned to Prague with the draft of

the new agreement in his pocket. The Air Ministry could do nothing but wait

upon events. Five weeks of silence passed. Then, in mid-May, a top secret

telegram arrived from Wyatt which indicated that new Soviet aircraft, possibly

as many as ninety, were flying in from Russian bases and being positioned under

hangars in aerodromes across the Republic. In a state of some alarm, he

admitted that all ‘previous direct and indirect enquiries regarding Russian

equipment . . . have always received indefinite and evasive answers’. He

contacted Janoušek who told him that the draft Agreement had yet to reach the

Cabinet for discussion. Wyatt noted: ‘The delivery of Russian aircraft at this

time may be a Communist pre-election gambit, for the people are being told the

aircraft are a gift from the Russians.’ Janoušek told him that unofficial

sources said otherwise, that a high price was being charged, and that, in any

case, the general staff were now said to be uninterested in purchasing British

aircraft.

In early June, the Air Ministry lost patience and told Wyatt

to ascertain whether there would be firm orders or not, and to set 31 July as

the deadline, after which the aircraft would be supplied to another buyer. If

Wyatt replied, the document has not survived, but a note from him to the Air

Ministry sent on 2 September 1946 confirmed that the agreement had still not

yet been signed. From that date onwards, the files are silent.

The Communist takeover of power in the coup of February 1948

was immediately followed by a direct assault on former members of the

Czechoslovak wartime forces, first the ex-RAF, then the members of the

Czechoslovak army in the West, as they were considered to have been influenced

far too much by their surroundings and experiences during the war, and finally

non-Communist members of the Czechoslovaks from the USSR who had seen too much

during their service there. Within days of the coup, scores of officers and

NCOs were dismissed as politically unreliable, either because of their known

anti-communist views or because they were married to English girls.

Many of these started fleeing the country when they saw the

writing on the wall. Some fled on foot across the borders to Germany,

unfortunately were caught and jailed. Others left some with their families, in

‘borrowed’ aircraft and landed in Germany, Belgium, France and some made it

directly to England. To the Czechs Great Britain was a natural refuge, not only

because of the recent common fight against Germans but also primarily, because

its ideals of democracy and humane approach to all problems were the same for

which they themselves had fought and for which many had given their lives. Of

those airmen who came to Britain, and there were several hundred, many were

accepted back into the Royal Air Force. Others dispersed all over the world

with the result that the ‘Free Czechoslovak Airforce Association Abroad’ had

members not only in Europe but also in the USA, Australia, Brazil and South

Africa.

Those who for various reasons did not or couldn’t go into

exile for the second time paid dearly for their wartime past. They were

considered unreliable, a threat to the revolution, many were arrested, sent to

prison, to labour camps (mainly into mines) or so called rehabilitation

centres. Even Colonel Fajtl, the Commander of the Czechoslovak fighter regiment

in the USSR and other members of his unit were incarcerated in the ’50’s. In

these years of terror and darkness, monster trials took place in which many

officers were sentenced to death or life imprisonment. Among them General Pika

and Air Marshal Janoušek, the former was executed, the latter’s sentence was

commuted to life of which he served 13 years.

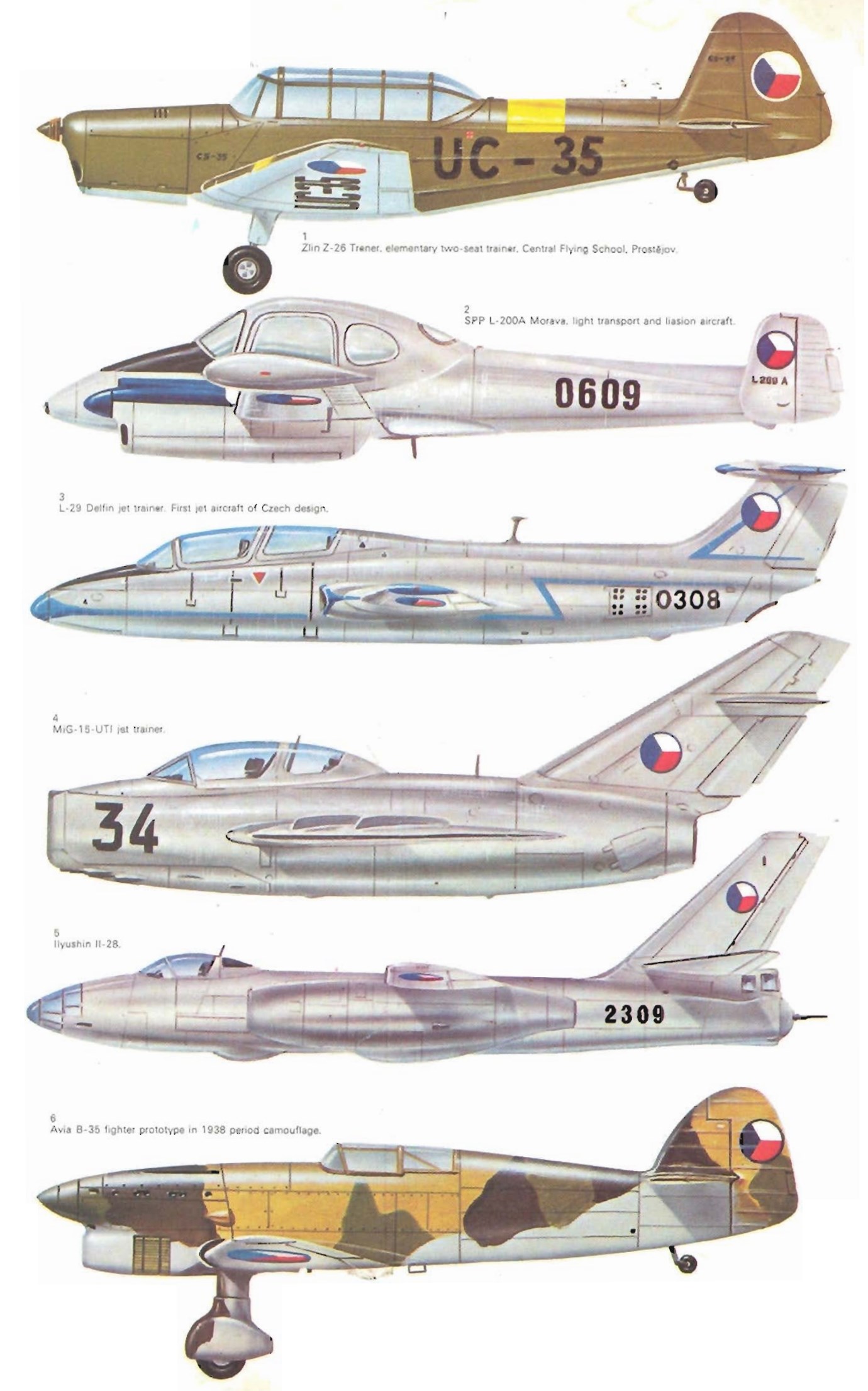

In 1955 Czechoslovakia became a founder member of the Warsaw

Pact. The Czechoslovak Air Force was equipped with Soviet aircraft and followed

its doctrines and tactics. Mostly Mikoyan-Gurevich aircraft (MiGs) were bought.

MiG-15, MiG-19, and MiG-21F fighters were produced under licence; in the 1970s,

MiG-23MF were acquired, followed by MiG−23MLs and MiG-29s in the 1980s.

In 1951 the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Air Defence Districts of State

Territory were created, at about the same time as the creation of the 15th

Fighter Air Corps. The 15th Fighter Air Corps controlled the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and

166th Fighter Air Divisions at various times; the 166th Fighter Air Division

later became the 2nd Fighter Air Division. From 1964 to 1969 the 10th Air Army

included the 46th Transport Air Division, of two regiments of helicopters and a

transport regiment.