On 2nd April 1946 I. V. Stalin, Chairman of the Council of

People’s Commissars, held a briefing on the prospects of Soviet aviation,

including jet aircraft development. One of the items on the agenda was the

possibility of copying the Messerschmitt Me 262A-1 a fighter, an example of

which had been evaluated by GK Nil WS in August-November 1945, and putting it

into production at one of the Soviet aircraft factories. In its day the Me 262

had an impressive top speed of 850 km/h (459 kts) , heavy armament comprising

four 30-mm (1.18 calibre) cannons and was generally well designed. However, the

idea was rejected for various reasons.

By then several Soviet design bureau had a number of

high-speed aircraft projects in the making; many of them fell for the ‘German’

layout with two turbojet engines under or on the wings ala Me 262 (which,

incidentally, was also employed by the British Gloster Meteor). For instance,

Pavel O. Sukhoi’s OKB used it for the izdeliye K fighter, the Mikoyan OKB

developed a Me 262 look-alike designated 1-260, while the Lavochkin OKB came up

with the ‘160’ fighter (the first fighter to have this designation) and the

Alekseyev OKB with the 1-21 designed along similar lines. A notable exception

was the Yakovlev OKB because A. S. Yakovlev cordially disliked heavy fighters,

preferring lightweight single-engined machines. (Later Yakovlev did resort to

the twin-engined layout, but that was in the early 1950s when the Yakovlev OKB

brought out the Yak-120 (Yak-25) twinjet interceptor which lies outside the

scope of this book.)

As an insurance policy in case one OKB failed to achieve the

desired results, the Soviet government usually issued a general operational

requirement (GOR) for a new aircraft to several design bureau at once in a

single Council of People’s Commissars (or Council of Ministers) directive. This

was followed by an NKAP (or MAP, Ministerstvo aviatsionnoy promyshlennosti –

Ministry of Aircraft Industry) order to the same effect. This was also the case

with the new jet fighters. Initially all the abovementioned OKBs designed their

fighters around Soviet copies of the Jumo 004B or BMW 003A engines; later the

more promising indigenous TR-1 came into the picture.

It should be noted that in the early postwar years the

Soviet defence industry enterprises continued to operate pretty much in wartime

conditions, working like scalded cats. In particular, the Powers That Be

imposed extremely tight development and production schedules on the design bureau

and production factories tasked with developing and manufacturing new military

hardware. The schedules were closely monitored not only by the ministry to

which the respective OKB or factory belonged but also by the notorious KGB.

‘Missing the train’ could mean swift and severe reprisal not only for the OKB

head and actual project leaders but also for high-ranking statesmen who had

responsibility for the programme. Nevertheless, even though the commencement of

large-scale R&D on jet aircraft had been ordered as far back as May 1944,

no breakthrough had been achieved by early 1946. For instance, the aircraft

industry failed to comply with the orders to build pre-production batches of

jet fighters in time for the traditional August fly-past held at Moscow’s

Tushino airfield; only two jets, the MiG-9 and Yak-15, participated in the fly-past

on that occasion. This was all the more aggravating because jet fighters had

been in production in Great Britain since 1944 and in the USA since early 1945.

Unfortunately the Soviet aero-engine factories encountered major difficulties

when mastering production of jet engines; hence in early 1946 jet engines were

produced in extremely limited numbers, suffering from low reliability and

having a time between overhauls (TBO) of only 25 hours.

As was customary in the Soviet Union in those days, someone

had to pay for this, and scapegoats were quickly found. In February-March 1946

People’s Commissar of Aircraft Industry A. I. Shakhoorin, Soviet Air Force

C-in-C Air Marshal A. A. Novikov, the Air Force’s Chief Engineer A. K. Repin

and Main Acquisitions Department chief N. P. Seleznyov and many others were

removed from office, arrested and mostly executed.

The early post-war years presaged the Cold War era, and the

Soviet leaders attached considerable importance not only to promoting the

nation’s scientific, technological and military achievements but also to flexing

the Soviet Union’s military muscles for the world to see. This explains why the

government was so eager to see new types displayed at Tushino, regardless of

the fact that some of the aircraft had not yet completed their trials – or,

worse, did not meet the Air Force’s requirements. Thus, the grand show at

Tushino on 3rd August 1947 featured a whole formation of jet fighter

prototypes: the Yak-19, the Yak- 15U, the Yak-23, three Lavochkin designs – the

‘150’, the ‘156’ and the ‘160’, plus the MiG- 9, the Su-9 and the Su-11 .

Sometimes the initial production aircraft selected for the fly-past

lacked armament or important equipment items. This was not considered

important; the world had to see the new aircraft at all costs. Behold the

achievements of socialism! Feel the power of the Soviet war machine! Fear ye!

Still, despite this air of ostentation, the achievements and the power were

there beyond all doubt; the Soviet Union’s progress in aircraft and aero engine

technologies was indeed impressive, especially considering the ravages of the

four-year war. It just happened that, because of urgent need, some things which

could not be developed in-country quickly enough had to be copied; and copied

they were – and with reasonably high quality at that.

Thus by the end of the 1940s the Soviet Union had not only

caught up with the West as far as jet aviation was concerned but gained a lead

in certain areas. The first Soviet jet fighters dealt with in this book were

instrumental in reaching this goal.

Even before the end of World War 2 it was clear that the

future of combat aircraft lay with jet engine power. German designs, although

limited in their application, had shown to many the shape of things to come and

the British and Americans were moving quickly to develop their jet fighters.

The Soviets were at first slow to catch up mainly due to the

fact that they had no domestic turbojet engine which was effective enough to

base a fighter upon. The Soviet designer Arkhip Lyul’ka had been working on

axial turbojets during the war but they weren’t as effective as the German

engines, while the Americans and British, seen now as the main rivals to the

Soviet Union, were far advanced with good coaxial engines and some centrifugal

jet engines. The leading jet engine of the time was the British Rolls-Royce

Nene, which with nearly 5,000lbs of thrust had double the power of any German

engine as well as other advantages.

The Russians had decided at the end of the war to loot what

they could of German industry and talent to rebuild their economy and this

attitude continued in their approach to jet fighter development. The Soviet design bureaus (OKBs) responded to

Stalin’s order to quickly develop jet fighters by using former German

specialists in gas turbines, aerodynamics and other technologies to catch

up with the Western powers’ technological advantage. The three main Soviet aircraft designers

Mikoyan and Gurevich (MiG), Yakovlev (Yak) and Lavochin (La) were tasked to

build jet fighters based on soviet air frames but using German engines.

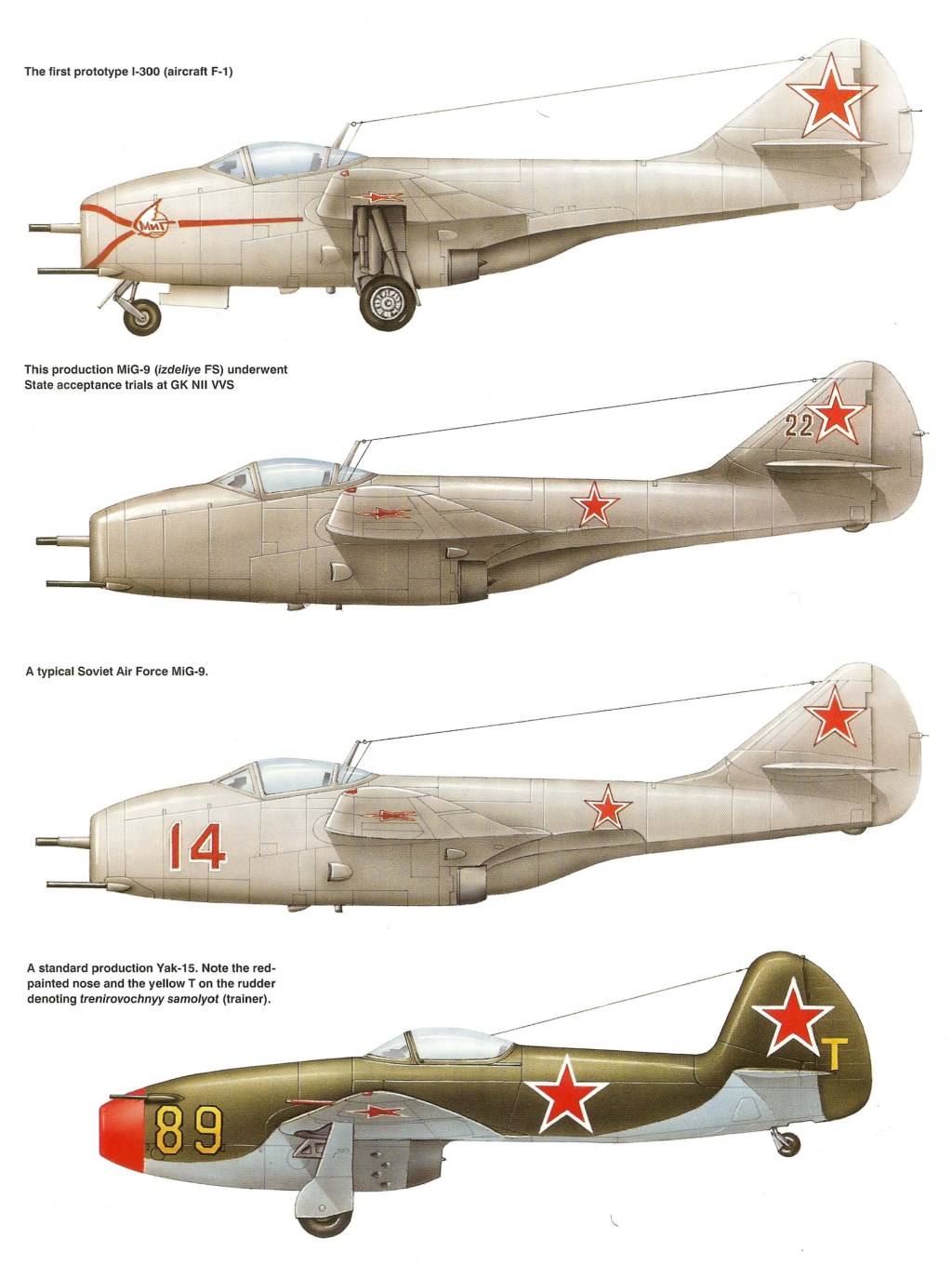

The first of these two hybrids were the MiG-9 which had

engines based on BMW 003A engines and the Yak-15. The MiG-9 had been on the drawing board

before the German surrender and was to use the weaker Lyul’ka engines. A fourth

designer (Sukhoi) had also been developing a jet fighter – the Su-9 – which

apart from having straight rather than swept wings looked remarkably like a

Me262. It was this similarity which was to doom the aircraft when in 1946

Alexander Yakovlev went to see Stalin and told him that the Su-9 was just a

Me262 copy and outdated and dangerous. It was cancelled and Yakovlev had

effectively put a rival out of the race. Yakovlev’s design was based on his

successful Yak-3 design (variants of which would continue to serve into the Korean

War). The design drawings were finished in just 3 days and three months later

in May 1945 detailed plans were complete for what was to become the Yak-15

‘Feather’. The Yak-15 was short ranged but agile and well-armed with two 23mm

cannon. Despite his political and design skill Yakovlev was to loose the race

to have the first Soviet jet fighter to fly.

Ready to fly at the end of 1945 a waterlogged runway at the Moscow test

site and internal politics meant that the Yak-15 was made to wait till the

MiG-9 ‘Fargo’ prototype was also ready.

On 24th April 1946 both were ready. Apparently a coin was tossed to see

which plane flew first and the MiG team won, so the MiG-9 flew first followed

by the Yak-15 a few minutes later.

Both of these fighters were simple but gave Soviet pilots

valuable experience of jets. The MiG-9 was used mainly as a ground attack

fighter while the Yak-15 developed into the Yak-17 which had wingtip fuel

tanks, tricycle landing gear and a more powerful engine. Over 400 were built

and some exported. Meanwhile Yakovlev’s old rival, Lavochkin was having little

success. In September 1946 the La-150 flew but was outdated in its design and

performed poorly compared to the Yaks.

On 24th June 1947 the La-160 flew the world’s first swept

wing fighter but Lavochkin had fallen from favour and was destined to create

‘also rans’ for the rest of the early Soviet jet fighter race. He was aided by

some strange good fortune when the Soviets were given some of the best British

jet engines by the Labour government of Prime Minister Attlee. Lavochkin

quickly produced the La-168, 174D, 176 and 180 all using engines based on the

Rolls-Royce engines the Soviets had been given. The La-176 was the first

aircraft in the world to have wings swept back at 45 degrees and with the help

of its engine based on the Rolls-Royce Nene it was the first European fighter

to break the sound barrier (Mach 1) in a shallow dive on 26th December 1948.

About 500 of Lavochkin’s fighters were produced but handling problems dogged

them and they were soon over shadowed by the success of MiG.

Meanwhile MiG whose OKB had been founded in 1939 began to

dominate Soviet combat aircraft design – a dominance that continues to this day

to a large extent. MiG also benefited from the British engines as some of their

best designs were hampered by the lack of a good engine. This problem now

solved, their aircraft S was to become the legendary MiG-15 ‘Fagot’, which flew

on 30th December 1947. The Nene engine fitted it perfectly and the combination

of a great design and a great engine was to be a world beater. The impact of

the MiG-15 on the Korea war was drastic; facing the US F-86 Sabres it could

match them for speed but had longer range and longer ranged more powerful guns

in the shape of its one 37mm cannon and twin 23mm cannons compared to the

Sabre’s six 12.7mm machine guns. This meant that although the Sabre pilots

could hit more often the MiG pilots could open fire at far greater range. The

MiG-15 was produced in huge numbers and some were still being used more 40

years after the first one flew.