This would normally have been the moon stand-down period for

the Main Force, but a raid to the distant target of Nuremberg was planned on

the basis of an early forecast that there would be protective high cloud on the

outward route, when the moon would be up, but that the target area would be

clear for ground-marked bombing. A Meteorological Flight Mosquito carried out a

reconnaissance and reported that the protective cloud was unlikely to be

present and that there could be cloud over the target, but the raid was not

cancelled.

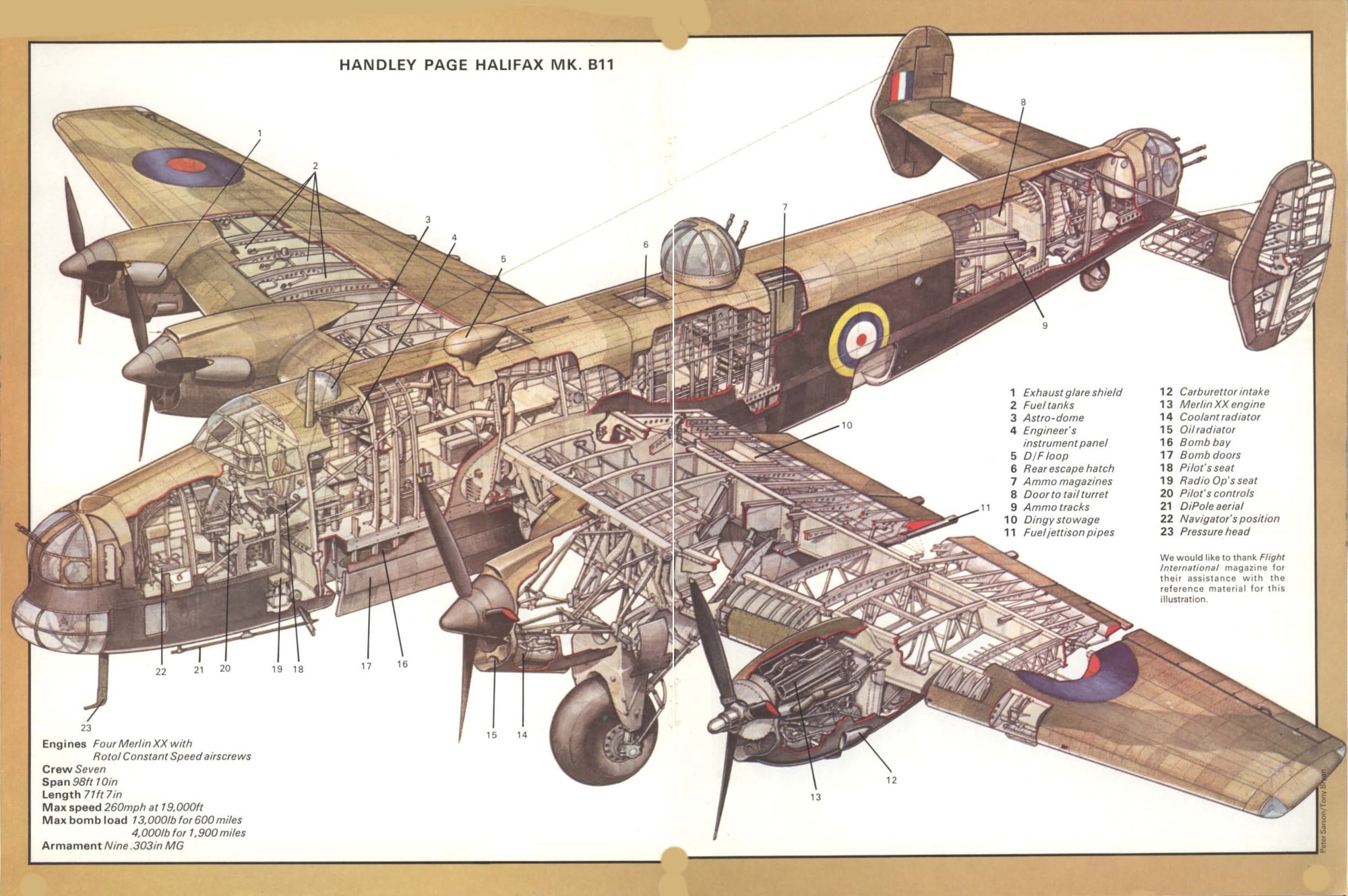

795 aircraft were dispatched – 572 Lancasters, 214 Halifaxes

and 9 Mosquitoes. The German controller ignored all the diversions and

assembled his fighters at 2 radio beacons which happened to be astride the

route to Nuremberg. The first fighters appeared just before the bombers reached

the Belgian border and a fierce battle in the moonlight lasted for the next

hour. 82 bombers were lost on the outward route and near the target. The action

was much reduced on the return flight, when most of the German fighters had to

land, but 95 bombers were lost in all – 64 Lancasters and 31 Halifaxes, 11.9

percent of the force dispatched. It was the biggest Bomber Command loss of the

war.

The bomber dived

violently and turned to the north, but because of good visibility we were able

to keep him in sight. I now attempted a second attack after he had settled on

his course, but because the Lancaster was now very slow we always came out too

far to the front. I tried the Schräge Musik again and after another burst the

bomber fell in flames.

The words belong to Oberleutnant Helmut Schulte of II./NJG 5

as he describes the last moments of a Lancaster on the night of 30/31 March

1944. The target that night was the ancient city of Nuremberg, the shrine of

Nazism, and flying a Bf 110G-4 fitted with Schräge Musik his success

contributed to what turned out to be Bomber Command’s worst night of the war.

The choice of target, deep in the heart of Bavaria in

southern Germany, was an interesting one, as it was not considered to be of

industrial importance. There were, however, several small factories around the

city and it was a central link in rail and water communications. But any route

taken to Nuremberg meant passing close to known heavily defended areas.

Furthermore, the moonlight meant that it should have been a period of

stand-down for the Main Force but a favourable weather forecast, with

protective cloud cover all the way to the target and clear conditions over

Nuremberg, led to the decision being made to go ahead with this distant raid.

The Bomber Command pump was again full-on with the squadrons

producing aircraft and crews in large numbers. It had been less than a week

since the last raid against Berlin (which had involved 800 aircraft) and just

four nights since Essen (over 700), but, even so, 795 aircraft were made

available for the Nuremberg raid.

For the Beetham crew of 50 Squadron it was to be their

twenty-first op. Their experience that night is best told through the words in

Les Bartlett’s wartime diary:

Such a nice day today,

little did we know what was in store for us. Briefing was getting later each

day as the days grew longer, and today it was 5 pm, so we all had an afternoon

nap. The target was Nuremberg. Where was that? ‘Oh, this should be a nice quiet

stooge’, someone said, but that remained to be seen. At 10 pm we taxied out and

were first airborne. Everything was quiet during the climb to 20,000 feet over

the Channel. We crossed the enemy coast and it was eyes wide open. As we drew

level with the south of the Ruhr Valley, things began to happen. Enemy night

fighters were all around us and, in no time at all, combats were taking place

and aircraft were going down in flames on both sides. So serious was the

situation, that I remember looking at the poor blighters going down and

thinking to myself that it must be our turn next, just a question of time. A

Lancaster appeared on our port beam, converging, so we dropped 100 feet or so

to let him cross. He was only about 200 yards or so on our starboard beam when

a string of cannon shells hit him and down he went. We altered course for

Nuremberg, and I looked down at the area over which we had just passed. It

looked like a battlefield. There were kites burning on the deck all over the

place – bombs going off where they had been jettisoned by bombers damaged in

combat, and fires from their incendiaries across the whole area. Such a picture

of aerial disaster I had never seen before and hope to never see again. On the

way into the target, the winds became changeable and we almost ran into the

defences of Schweinfurt but we altered course in time. The defences of

Nuremberg were nothing to speak of, a modest amount of heavy flak which did not

prevent us doing a normal approach, and we were able to get the target indicators

dropped by the Pathfinders in our bombsight to score direct hits with our

4,000lb ‘Cookie’ and our 1,000lb bombs and incendiaries. We were able to get

out of the target area, always a dodgy business, and set course for home. To

reach the coast was a binding two-hour stooge. The varying winds were leading

us a dance. We found ourselves approaching Calais instead of being 80 miles

further south, so we had a slight detour to avoid their defences. Once near the

enemy coast, it was nose down for home at 300 knots. Even then, we saw some

poor blokes ‘buy it’ over the Channel. What a relief it was to be flying over

Lincoln Cathedral once more. Back in debriefing, we heard the full story of the

squadron’s effort. It was the worst night for the squadron.

Bartlett and his crew had been lucky. It appears the weather

forecast had been wrong and several wind-finding errors were made, causing the

Main Force to become scattered. One-in-five bombers, it is reckoned, missed one

of the turning points by at least 30 miles.

For the experienced crews who had spent the past few months

clawing their way through varying densities of cloud to attack the major cities

in Germany, including Berlin, the conditions just did not feel right. An

attempt to deceive the German controllers of the intended target had failed;

the lack of H2S transmissions coming from the Mosquitos carrying out spoof

attacks against Cologne and Kassel making these attempts to deceive the

defences easily recognized for what they were. And if this was not bad enough,

a long straight leg of 270 miles to the target made the actual area of attack

predictable.

Everything seemed to favour the defenders. Not only had the

bombers become scattered over a wide area, the atmospheric conditions meant

that condensation trails from their engines formed at a much lower height than

normal. Also, there had been little or no cloud over much of Belgium and

eastern France, and even where there was some cloud it was very thin and

offered little or no protection. Over Holland and the Ruhr the sky was clear

and the bright half-moon lit up the trails, making the bombers visible from

many miles away.

The first night fighters appeared before many of the Main

Force had even reached the Belgian border, enabling them to constantly harass

the bombers for the next hour. Falling bombers merely presented a trail of

fires as they crashed to earth. By the time the Main Force approached Nuremberg

some eighty bombers had been shot down with dozens more having aborted their

mission either because of damage sustained or for other technical reasons.

Helmut Schulte was one to get amongst the main bomber stream

at 20,000 feet with ease. In Spick’s Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Schulte described

what happened next:

I sighted a Lancaster

and got underneath it and opened fire with my slanting weapon. Unfortunately it

jammed, so that only a few shots put out of action the starboard inner motor.

The bomber dived violently and turned to the north, but because of good

visibility we were able to keep him in sight. I now attempted a second attack

after he had settled on his course, but because the Lancaster was now very slow

we always came out too far to the front. I tried the Schräge Musik again and

after another burst the bomber fell in flames.

For the bomber crews that did make it to Nuremberg they

arrived over the city to find it covered by thick cloud, which extended up to

15,000 feet. It was not at all what had been briefed. Having expected the

target to be clear of cloud, the Pathfinders carried mostly ground markers, which,

of course, could not be seen through the cloud. Most of the bombs fell in

residential areas, with only slight damage caused to industry.

Because of the problems caused by the wind, more than a

hundred bombers had become so straggled that it is likely they bombed

Schweinfurt, to the north-west of Nuremberg, instead. This belief is backed up

by some post-raid reports of crews that had passed to the west of Schweinfurt

on their way home. Pilot Officer John Chatterton of 44 Squadron, an experienced

skipper flying his twenty-third op that night, later recalled what his crew had

seen after leaving Nuremberg for the long journey home:

… after several

minutes they [his air gunners] called our attention to another target away over

to our right which seemed to be cloud free and with a lot of action. Tongue in

cheek I asked Jack [his navigator] if he was sure we had bombed Nuremberg and

received the expected forceful reply, with added information that the burning

town was probably Schweinfurt.

Helmut Schulte, meanwhile, claimed three more bombers before

coming across another Lancaster to the south of Nuremberg. When the bomber went

into an immediate corkscrew he knew he had been spotted. With his Schräge Musik

jammed, Schulte had no choice but to opt for his forward-firing guns but on

this occasion his attack did not bring any success as he later recalled:

As soon as I opened

fire he dived away and my shells passed over him. I thought that this chap must

have nerves of steel: he had watched me formate on him and then had dived just

at the right time. He had been through as much as I had – we had both been to

Nuremberg that night – so I decided that was enough.

Schulte’s performance that night was impressive but it was

bettered by another Bf 110 pilot, Oberleutnant Martin Becker, the

Staffelkapitän of 2./NJG 6, who claimed seven bombers during the raid. Six of

his victims – three Lancasters and three Halifaxes – all came down over Wetzla

and Fulda in central Germany in a matter of minutes while the seventh, another

Halifax, was claimed over Luxembourg while Becker was returning to base. These

latest successes took his score past twenty, thirteen of which had been claimed

in just over a week, earning him the Knight’s Cross and command of the 4th

Gruppe.

Not only was the Nuremberg raid a failure, it turned out to

be the worst night for Bomber Command of the war. Ninety-five aircraft were

lost, of which seventy-nine fell to the night fighters. These figures might

have been even higher had some Bf 110s not have been sent too far to the north.

A further ten more bombers were written off after crash-landing back at base

and a further fifty-nine had sustained considerable damage.

Leaving aside those aircraft that had been damaged, the

overall loss rate for the raid was in excess of 13 per cent, with a reported

535 lives lost and a further 180 wounded or taken as prisoners of war. The

Halifax force had again suffered the heaviest losses. Including the five

written-off back in England, thirty-six of the 214 aircraft taking part in the

raid had been lost (16.8 per cent). 51 Squadron based at Snaith in Yorkshire

had suffered particularly badly with six of its seventeen Halifaxes failing to

return, with the loss of thirty-five lives.

One young Halifax pilot to be killed that night was

22-year-old Pilot Officer Cyril Barton of 578 Squadron based at Burn in North

Yorkshire. Flying Halifax ‘LK-E Excalibur’, Nuremburg was his nineteenth op.

For most of the transit to the target he had been fortunate to avoid any

trouble but the first he and his crew became aware of immediate danger was when

they spotted pale red parachute flares, dropped by Ju 88s to mark the position

of the bomber stream.

The sky was clear and the crew watched in horror as night

fighters suddenly appeared. One by one their colleagues were picked off. They

knew it would soon be their turn but they were now on the final leg towards the

target and there was to be no turning back. Suddenly, two night fighters

appeared in front. They were seen attacking head-on just as cannon shells

ripped through the Halifax, puncturing fuel tanks and knocking out the

aircraft’s rear turret and all of its communications while setting the starboard

inner engine on fire.

Barton threw the aircraft into a hard evasive manoeuvre just

as a Ju 88 passed close by. Corkscrewing as hard as he dare, the Halifax went

down. For a while it seemed the danger had passed but no sooner had Barton

resumed his course towards Nuremberg than the Halifax was attacked once again.

Shells raked the fuselage for a second time. Again, the Ju 88 broke away but it

was soon back again, scoring more hits on the crippled bomber before eventually

turning away.

Undaunted, Barton again resumed his course for Nuremberg. He

was finally able to gather his thoughts and to assess the damage to his

aircraft, only to find that three of his crew members had gone. Unable to

communicate with their skipper, and with the bomber repeatedly under heavy

attack while corkscrewing towards the ground, the navigator, bomb aimer and

wireless operator had all abandoned the aircraft to become prisoners of war.

Left in a desperate situation, Barton decided what to do

next. With a crippled bomber, one engine out, leaking fuel, his rear turret out

of action, no communications or navigational assistance, and now with three of

his crew missing, he would have been fully justified in aborting his mission.

But he decided instead to press on to the target with just his two air gunners,

Sergeants Freddie Brice and Harry Wood, and his flight engineer, Sergeant

Maurice Trousdale, left on board.

The four airmen struggled on as best they could. By working

together and using the stars to navigate, they eventually reached the target

and completed their attack before finally turning for home. Remarkably, they

managed to keep out of further trouble as Barton nursed the crippled Halifax

back towards safety. It was an outstanding feat of airmanship for a pilot so

young. But the crew were still not out of danger and although Barton was

satisfied they had coasted-in somewhere over eastern England, they still had to

find somewhere to land.

It was just before 6 a.m. and still dark but the Halifax was

now desperately short of fuel. As Barton eased the bomber down he was all too

aware that the remaining engines were about to give up. With his three crew

colleagues braced behind the aircraft’s rear spar, he was all alone in the

cockpit.Visibility was extremely poor and suddenly a row of terraced houses

appeared in front. Yanking the control column back in a desperate attempt to

hurdle the obstacles before him, a wing first clipped the chimneys before the

Halifax came crashing down, demolishing everything in its way.

The Halifax had come down in the yard of Ryhope colliery in

County Durham. One miner on his way to work, 58-year-old George Dodds, was

killed in the wreckage. Remarkably, though, the three crew members braced in

the rear of the fuselage had survived; all to later receive the DFM.

Fortunately for them, the rear section of the aircraft had broken away on

impact. The forward section, however, still with the gallant young pilot

inside, was a wreck of twisted metal. Barton was pulled from the wreckage and

rushed to hospital but he died from his injuries the following day.

It was an extraordinary act of courage and words are

difficult to find. A few weeks later came the announcement of the posthumous

award of the Victoria Cross to Cyril Barton. The citation, which appeared in

the Fifth Supplement to the London Gazette on Friday 23 June 1944, concludes:

In gallantly

completing his last mission in the face of almost impossible odds, this officer

displayed unsurpassed courage and devotion to duty.

Pilot Officer Barton’s Victoria Cross was the only one

awarded during the Battle of Berlin, which had now officially ended.

The disastrous raid against Nuremberg was yet another costly

reminder that large-scale raids deep into Nazi Germany were still extremely

hazardous and often resulted in heavy losses. Unfortunately for all the bomber

crews lost during the long and hard winter of 1943/44, they had come up against

the Luftwaffe’s night fighter force at the peak of its effectiveness.

It was, for now, the last all-out offensive against the

German homeland and brought to an end Bomber Command’s long-employed tactic of

massed attacks against major targets. Not until the Allies enjoyed air

superiority over north-west Europe would Bomber Command employ such tactics

again. If it had not been apparent before then it was certainly apparent now –

the war would not end until Germany had been defeated on the ground. However,

everything Germany needed to maintain both military and civil defence – water,

electricity, transport and emergency services – as well as the raw materials to

keep the factories going, had drawn heavily on its resources throughout that

hard winter. In truth, Germany was slowly grinding to a halt. The Nuremberg

raid had also marked the Nachtjagd’s last great victory of the war.

Most of the returning crews reported that they had bombed

Nuremberg but subsequent research showed that approximately 120 aircraft had

bombed Schweinfurt, 50 miles north-west of Nuremberg. This mistake was a result

of badly forecast winds causing navigational difficulties. 2 Pathfinder

aircraft dropped markers at Schweinfurt. Much of the bombing in the Schweinfurt

area fell outside the town and only 2 people were killed in that area.

The main raid at Nuremberg was a failure. The city was

covered by thick cloud and a fierce cross-wind which developed on the final

approach to the target caused many of the Pathfinder aircraft to mark too far

to the east. A 10-mile-long creepback also developed into the countryside north

of Nuremberg. Both Pathfinders and Main Force aircraft were under heavy fighter

attack throughout the raid. Little damage was caused in Nuremberg; 69 people

were killed in the city and the surrounding villages.

DIVERSION AND SUPPORT OPERATIONS

49 Halifaxes minelaying in the Heligoland area, 13 Mosquitoes

to night-fighter airfields, 34 Mosquitoes on diversions to Aachen, Cologne and

Kassel, 5 R.C.M. sorties, 19 Serrate patrols. No aircraft lost.

Minor Operations: 3 Oboe Mosquitoes to Oberhausen (where 23

Germans waiting to go into a public shelter were killed by a bomb) and 1

Mosquito to Dortmund, 6 Stirlings minelaying off Texel and Le Havre, 17

aircraft on Resistance operations, 8 O.T.U. sorties. 1 Halifax shot down

dropping Resistance agents over Belgium.

Total effort for the night: 950 sorties, 96 aircraft (10.1

percent) lost.