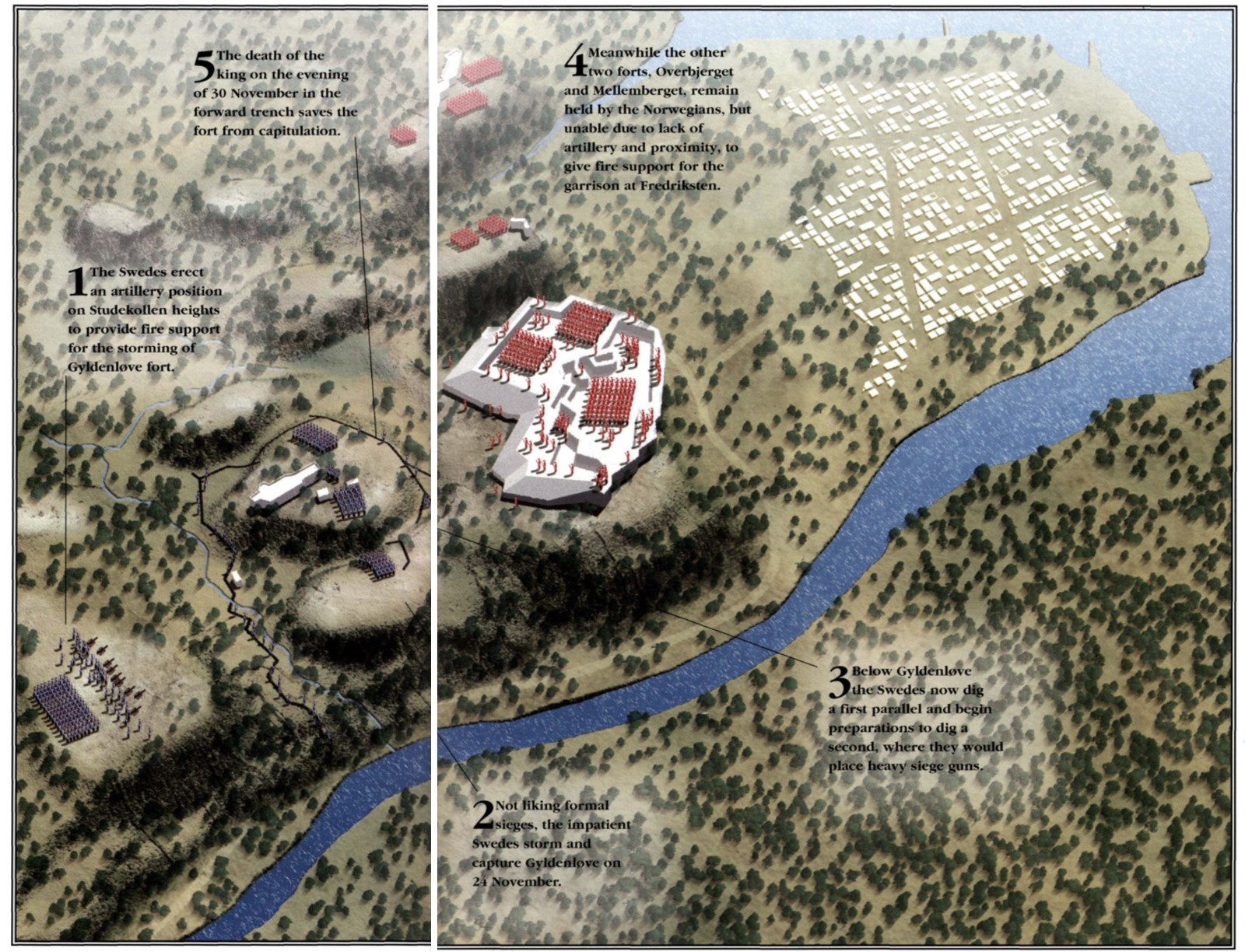

In October 1718 Swedish king Charles XII invaded southern Norway with

35,000 troops, determined to reduce the lynchpin of the enemy’s frontier

defences at Fredrikshald to rubble through a regular siege, led by a hired

professional French artillery officer, Colonel Maigret. The Swedes, commanded

in person by the king, stormed and captured the outer fort of Gyldenlove on 27

November. Three days later the Swedes, facing only 1400 enemy troops holding

the fortress of Fredriksten, dug a parallel trench to the fortress, followed by

an approach trench (to a second parallel), and seemed to be on the verge of a

great – and relatively easy – victory. Once the siege artillery had the

fortress within range it could be forced through bombardment to capitulate, as

Colonel Maigret had assured the king. But on 30 November Charles XII was killed

in the most mysterious of circumstances in the forward trenches, saving the

Norwegians from what would have been a humiliating defeat and eventual

occupation by their neighbours.

Galleys had been used in the Mediterranean Sea during the 16th century

but a lesser-known fact u’as that both Russia and Sweden used them during the

Great Northern War. Here teams of horses and men are pulling one such galley

across greased logs from the North Sea coast overland to the dark waters of the

Iddejjord, near Fredrikshald, in 1718.

Plan of the siege of Fredrikshald (Halden) and its fortress Fredriksten

in 1718. The engraved plan by Johann Baptist Homann shows the military

intervention of King Charles XII of Sweden during the Great Northern War in

1718. The siege ended unsuccessfully because the king was killed by headshots

and the siege was therefore discontinued. With decorative title banner and an

impressive naval battle.

The Great Northern War had been going on for 16 long years

when Sweden’s formidable warrior king, Charles XII, laid plans to invade Norway

in 1716. This country was only a stepping stone in his grandiose plans to

invade Britain, dethrone George I and crown James Stuart, before moving on to

deal with Denmark and Russia.

Charles’ plan in 1716 was for a blitzkrieg-style attack on

Norway with only a small army of 7700 men, in three columns. The Swedes hoped

that by treating the Norwegians with silk gloves they would welcome their

‘liberators’. The Swedes knew that their small invasion army faced a Norwegian

army twice their size. But it consisted of poorly equipped, badly trained

peasant recruits. As the aggressors the Swedes held the initiative, which

ensured that the Norwegian army was strung out along the long frontier not

knowing where or when the Swedes would strike. Norway was similar to Canada,

built like a natural fortress, especially in winter with frozen lakes, rivers,

marshes, wooded hills and endless forests sparsely sprinkled with small peasant

settlements. It was not an easy country for an invader to stage a

European-style campaign.

The Norwegians could also rely on the support of the Danish

Navy. Danish and Norwegian vessels led by Norway’s ‘Nelson’, Admiral Peter

Tordenskjold, disrupted Swedish coastal communications and prevented vital

supplies reaching the invading army. Sweden’s naval weakness was a major

problem for the plans Charles had laid. The Norwegians had also built a

formidable line of six major fortifications along the main river barrier in

eastern Norway, called the Glomma Line. To add further defences to this Glomma

Line the Norwegian commander, General Lützow, constructed field fortifications

at the two main hill passes blocking the entrance to Christiania. These field

forts were held by 1500 cavalry and 5600 infantry.

When Charles, who had crossed the frontier in early March,

reached this line his attack against one of these forts failed and he was

forced to retreat south. He then turned north but was surprised by the speed

with which his enemy erected a barrier of logs and felled trees that his troops

could not force. Like the Canadians, the Norwegians were adept at throwing up

defensive lines. But Charles marched his men across frozen ice on the Oslo

fjord to outflank his enemy, and by 21 March he was outside the empty Norwegian

capital.

Once news arrived of the Lion of the North’s approach the

population fled westwards. Christiania’s garrison of 3000 regulars had

plentiful supplies and was under the command of a tough German officer in

Danish service, Colonel Jörgen von Klenow. The Swedish invasion began to run into

difficulties with the Norwegian fortifications. Charles occupied Christiania on

22 March, but the town was built with its streets perpendicular to the

fortresses’ guns so that the guns could shoot straight down the street and onto

any Swede foolish enough to venture out. The Swedes tore up paving stones,

houses and anything else they could find to erect breastworks or dig trenches

to protect themselves. Assaults on other forts were beaten back with heavy

losses. Charles did not give up hope but his officers were pessimistic and a

defeatism that had marred the Swedish army’s morale since the catastrophic

defeat at Poltava in 1709 now surfaced. The officers feared they would be cut

off and starved into submission due to their long supply lines. Charles marched

south and took the town of Fredrikshald (present-day Halden) in July. However,

he could not take its fortress, Fredriksten, or the city’s inner defence wall,

which was held by an armed force of the town’s inhabitants.

When Charles invaded Norway again in 1718 his approach was

very different. If the Norwegians would not greet the Swedes as liberators then

they would be bludgeoned into submission and crushed by sheer military might.

Bearing in mind his experiences in 1716, he was determined to take Fredriksten

first. It was Norway’s most formidable fortress and it straddled Sweden’s

supply routes and the lines of communication all the way back to Sweden.

The first step in this plan was to get a galley flotilla

into the Iddefjord in order to reduce Sponviken fort and then bombard Halden

from the fjord as well from the land side. The flotilla would avoid having to

run the gauntlet of Fredrikstad’s fortress batteries and the deadly attentions

of Tordenskjold’s fleet hovering off the coast. Charles ordered 800 troops and

1000 horses to haul his galleys and gunboats across the peninsula between the

North Sea and Iddefjord.

Fredriksten, meaning Frederick’s rock, was built on top of a

massive granite mountain above the city of Fredrikshald on the Norwegian side

of Iddefjord, which connected in the west with the waters of Svinesund. On

three sides this eagle’s nest was protected by water, cliffs or deep valleys

and it was only to the south-east that it was open to attack. Even on that side

the approaches were protected by marshes and three forts.

This time Charles was taking no chances. He created a huge,

well-supplied army of 40,000 troops accompanied by a well-equipped siege train

led by a professional fortification officer with a wide experience of sieges.

The French colonel of fortification, Philippe Maigret, had been trained by

Vauban and now prepared to conduct a siege in this northern wilderness

according to his illustrious teacher’s masterly system. Fredriksten would be

completely encircled and cut off from the outside world. Parallel trenches

would be dug to surround the fortress in concentric circles. Approches would be dug to close in on

the fort and in such a way that they avoided its artillery. Then heavy siege

mortars and guns would be used to make a breach in the walls. Meanwhile,

Maigret told the Swedes, the garrison would become demoralized by their

isolation, the absence of news and the growing lack of supplies. Once this had

been done the Swedes could storm the fortress.

Swedish preparations had been so painstaking that the

invasion of Norway only began in late October. Charles arrived ahead of

schedule with 900 cavalry forcing the Norwegians to sink their transport

flotilla on Iddefjord. Nevertheless it was only by 20 November that the siege

artillery was in place. In total Charles had 35,000 men in southern Norway

while Colonel Landsberg, the Norwegian commandant of Fredriksten, admitted that

the fortress was totally cut off by the siege, and that he had only 1400 troops.

Charles could not resist taking risks and personally commanded a daring attack

on 27 November, which stormed and then took the outlying Gyldenl0ve fort.

The Swedes were now engaged in the tedious and unusual task

of digging trenches to approach Fredriksten. Hard and unpleasant work in the

rocky soil around the fortress, the troops dug in the face of Norwegian fire

from the main fort and the two remaining outer works. On 30 November the first

parallel was completed and a sap had been dug. Charles wanted Maigret to begin

digging the second line as soon as possible. Earlier Maigret had assured the

impatient king that the fortress would fall within eight days and even

Fredriksten’s commander, Colonel Landsberg, admitted that Fredriksten could not

hold out longer than a week.

As the soil was thin the Swedes had to reinforce their

trenches with 600 fascines and 3000 bags every day. Once the second parallel

had been dug and reinforced with breastworks Maigret’s siege artillery of 18

heavy pieces (six 16-kg [36-lb] howitzers and six 34-kg [75-lb] mortars) would

bombard the walls and make a breach. Landsberg knew that the walls had not been

properly embedded in the rock and that they would fall apart at the first

Swedish barrage.

Fortunately for the Norwegians Charles, always in the front

line, was in the sap during the evening of 30 November when, supposedly, a

stray bullet hit him in the head and killed him instantly. The Swedish officers

in command immediately ordered a retreat and all dreams of empire vanished. Today

it is thought that the bullet was probably fired by a hired assassin, paid by

the king’s ruthless and ambitious brother-in-law, Prince Frederick of Hesse,

who later became King Frederick I of Sweden.

PEDER TORDENSKJOLD, (1691-1720)

Danish admiral, was born Peder Wessel, tenth child of a

Bergen alderman, and as a young boy ran away to sea. After several voyages to

the West Indies he was appointed a second lieutenant in the Danish Navy and

within a year was commanding the 4-gun sloop Ormen, in which he operated

successfully off the Swedish coast. Within a year he was promoted to command a

20-gun frigate, in which his fine seamanship and audacity were given full play.

With the Great Northern War in full swing, he found no lack of action among the

fjords of Sweden in operations against Swedish frigates and troop transports,

and his fame as a brave and skillful commander began to spread. With the return

of Charles XII to Sweden in 1715, Wessel did great execution among the Swedish

shipping off the coast of Pomerania, and in the following year was ennobled by

Frederick IV of Denmark under the title of Tordenskjold (Thundershield). He

raised the siege by Charles XII of Fredrikshald in Norway by destroying the

Swedish fleet of transports and supply ships, and was promoted captain. In 1717

he commanded a squadron with the task of bringing to action and destroying the

Swedish Gothenburg squadron, but disloyalty on the part of some of his officers

prevented his achieving a decisive victory. Nevertheless, he was able to return

to Denmark in 1718 with the news of the death of Charles XII, and was made a

rear admiral by Frederick IV in the general rejoicing. His final claim to fame

was the capture of the Swedish fortress of Marstrand and the final elimination

of the Gothenburg squadron, partly by destruction and partly by capture. For

this he was advanced to vice admiral. Shortly after the end of the Great

Northern War he was killed in a duel. He is regarded in Denmark as a great

naval hero, and. after Charles XII perhaps, the most heroic figure of the Great

Northern War.