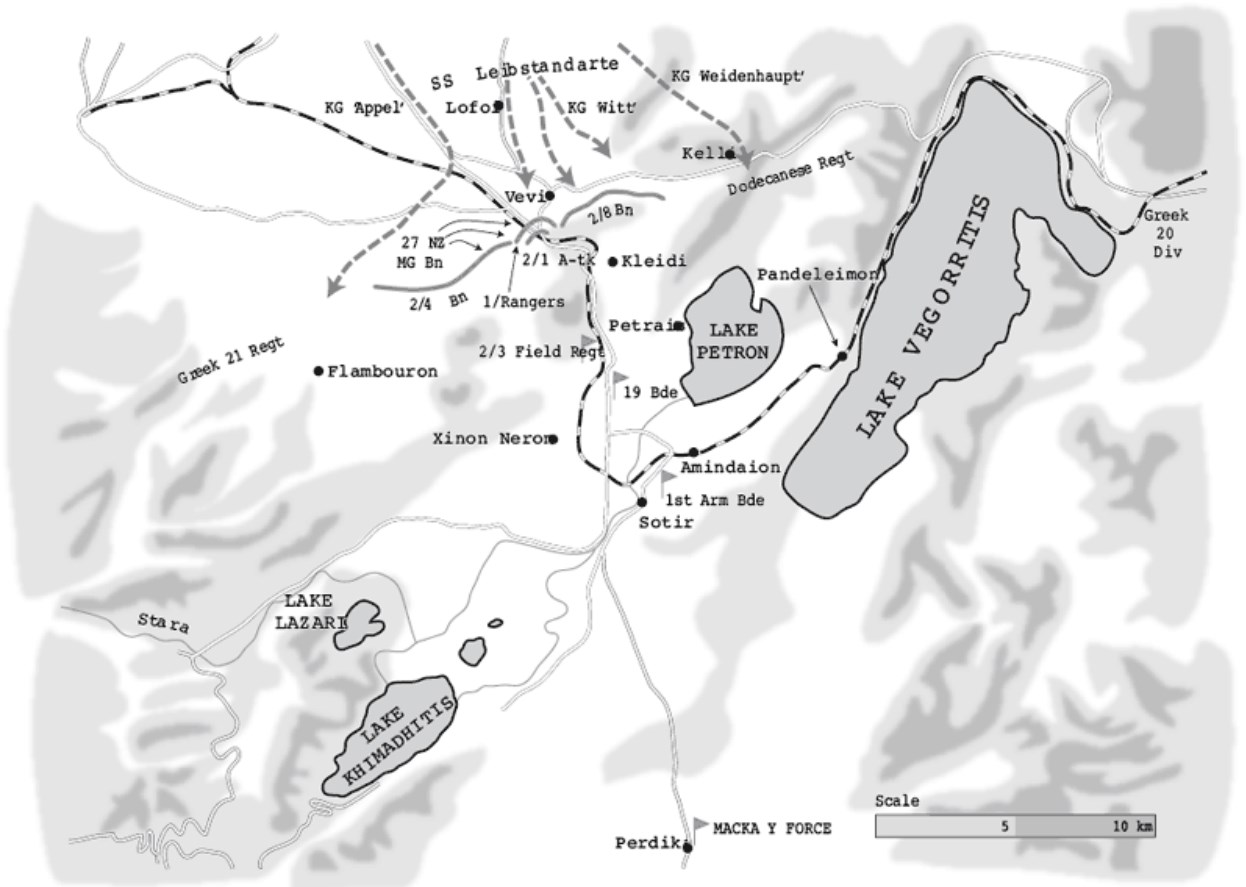

The Battle of Vevi, 10–13 April 1941

The Allied line had therefore already lost cohesion when

Witt launched his full assault from 2.00 p.m. This was supported in earnest by

the StuG III assault guns. Slocombe was astounded by their presence, as his

unit had been unable to get their feeble Bren-gun carriers onto the same

ground. Another 2/8th veteran, Jim Mooney, found the German armour

‘untouchable’ with the Boys rifle, the standard British anti-tank weapon for

infantry units. When the German armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs) came onto an

Australian position, there was little that could be done other than move back,

covered by the fire of a supporting section.

The collapse of the infantry line exposed the remaining

units in the valley who were preparing for the withdrawal. A detachment of the

2/1st Field Company was getting ready the last of the demolitions to break the

railway line deep in the pass, south of Kleidi, and Sergeant Scanlon, the

leader of this party, found his work interrupted mid-afternoon by the arrival

of the SS: ‘We commenced work at about 1500 hours, and had to do a hasty but

thorough job as the enemy was advancing both along the road and the railway

line with his armoured fighting vehicles.’ Scanlon’s attention to detail was

greatly assisted by the nature of the explosives he had to work with, which

included two naval depth charges, each with about 250 pounds of TNT packed

within. These were used to blow the road: the railway line was disposed of with

guncotton charges fixed to the rails. Scanlon readied his getaway car, which

was a ‘utility truck with a Bren gun mounted’. He ordered his men to light

their charges on the approach of the Germans and then, he describes:

[T]hey had just

sighted enemy movement and lit their fuses, when a German patrol, who had

worked their way onto a hill commanding this place, opened fire on them with

M.G.s. This was at approx 18.30 hrs and was about half an hour after completing

the preparation of the demolition. Luckily they got through, the two men on the

railway line having to run about 200 yards under fire to gain the vehicle.

With the Vevi position unravelling, Vasey, regrettably, was

out of touch with events. As Scanlan got about his work at 3.00 p.m. in the

shadow of the panzers, Vasey reported confidently to the 6th Division that he

‘had no doubt that if the position did not deteriorate he would have no

difficulty in extricating the Brigade according to plan’.

An officer of the 19 Brigade thought the atmosphere at

brigade headquarters that afternoon was ‘almost too cool and calm’, and the

implied criticism was warranted. Vasey had wanted to find a headquarters

position further forward, but had not found anywhere suitable: as a result, the

battle was determind while the Australian commander could only react to events.

At 5.00 p.m., Vasey at last informed 6th Division

headquarters that the situation was serious. In response, at 7.45 p.m. the 6th

Division sent forward a driver with a message authorising Vasey to bring

forward the withdrawal at his discretion; but, in the chaos, the driver could

not find him. By then, the position was a good deal worse than serious — the

2/8th was in desperate trouble, having its left flank exposed by the collapse

of the 1/Rangers, and outflanked on the right by the withdrawal of the Dodecanese.

The strong Allied artillery force at the southern end of the pass was under

small-arms and mortar fire by the time of Vasey’s message, forcing the 2/3rd

Field Regiment to pull back its 5th Battery, while its 6th Battery covered the

movement with fire over open sights — a sure sign that the defence was in

trouble, because it meant that the defending gun line was under direct attack.

Even Vasey’s own brigade headquarters was under mortar attack. Vasey had little

choice but to warn the 2/4th battalion commander, I. N. Dougherty, to get ready

to withdraw. ‘The roof is leaking,’ he told Dougherty; as a consequence, the

2/4th had ‘better come over so we can cook up a plot’. Vasey at least took the

sensible precaution of ordering his transport to remain where it was: had it

come up as arranged, it may well have been mauled by the German armour, and the

means to extricate the Allied force may have been lost. He also sent back to

the 6th Division a liaison officer to give Mackay an eyewitness report: he arrived

at 8.30 p.m., and Mackay thereby learned of the ‘increasing pressure’ on the 19

Brigade and of the discomfiture of the 2/8th Battalion.

Meanwhile, at the 2/8th Battalion headquarters, Mitchell

attempted to regain contact with brigade headquarters, the phone line having

gone dead. Two signallers sent to repair it were not seen again, so at 4.45

p.m. he despatched his signals officer, Lieutenant L. Sheedy, to the rear to

report on the battalion’s plight. Sheedy found what he described as a tank

(again, almost certainly a StuG III) already astride the road outside Kleidi,

basking in the flames of a wireless truck it had destroyed. The presence of

this vehicle cut the most direct and easiest line of withdrawal along the road.

Sheedy also observed parties of Germans armed with sub-machine-guns chasing the

fleeing 1/Rangers over the neighbouring hills.

By skirting trouble, and gaining shelter behind one of the

few light tanks of the 4th Hussars behind the battlefront, Sheedy gained the

forward position of the 2/3rd Field Regiment. Even as he gave his report, the

artillery headquarters came under German machine-gun fire, and there was

nothing in any event that could be done for the 2/8th, as the observation posts

needed by the artillery for accurate fire had been swept away in the collapse.

Liley, with the Kiwi machine-gunners, had already concluded that, as far as he

could see, ‘there was no infantry reserve and no tanks or anything else to

restore the position’, so he led his platoon to the rear. For extricating his

men and their guns under fire, Liley received the Military Cross.

A conference of company commanders of the isolated 2/8th was

called at 5.00 p.m., but Mitchell unwisely did not go forward to attend it,

instead sending his adjutant, Captain N. F. Ransom: Mitchell apparently thought

he was needed in the rear to restore communications with brigade headquarters.

As soon as this command conference got under way, it was shelled by a tank on

the ridge where C Company should have been, and subjected to machine-gun fire

from the left. Under these anxious circumstances, the Australian commanders

decided to withdraw in succession from the left. By now, three StuG III assault

guns, together with an estimated 500 enemy infantry, were firmly ensconced on the

position of C Company. One man from the 18 Platoon who stood up from his weapon

pit at this time was blown apart by a direct hit from a 75-millimetre shell. B

Company was assailed on three sides, and the battalion headquarters,

medical-aid post, and ammunition dump were all under machine-gun fire. On the

right, A Company was being flanked as the Dodecanese fell back under pressure

from Kampfgruppe Weidenhaupt.

In these desperate circumstances, a staged withdrawal was

impossible and the retreat of the 2/8th Battalion became a rout. Denied the use

of the road by German armour, the Australian infantry faced a march of 19

kilometres across waterlogged ridges to the reserve position, chased all the

way by bloodthirsty packs of SS infantry. Men of their own volition began

discarding their heavier weapons, particularly the useless Boys anti-tank

rifle, but also the much more efficient Bren gun. D Company, the last to leave

the forward position, was naturally under the most strain: the company’s

second-in-command, Lieutenant S. C. Diffey, resorted to ordering his men to

abandon their personal weapons to speed their escape. Such an order was nearly

unthinkable in a disciplined military force and, when he learned of it, Vasey

was unimpressed. He annotated the 19 Brigade war diary with the observation

that after the action, the 2/8th could only raise 50 armed men, and wrote that

Mitchell was ‘completely exhausted’.

Bob Slocombe of the beleaguered 14 Platoon eventually came

across some British tanks, and was carried out on the back of one; many of his

companions in the 2/8th were not so lucky, and only 250 answered the battalion

rollcall that night in the village of Rodona. Mitchell, the battalion

commander, got as far back as Perdika, and was interviewed there by the 6th

Division CO Iven Mackay who, with possible understatement, thought Mitchell ‘a

bit upset’. When Mackay learnt later that men of the 2/8th came back without

their personal weapons, he was incensed: ‘It is my intention to hold an enquiry

into this position to ascertain how and why so many members of this Bn

[Battalion] came to be separated from their weapons.’ This inquiry never got

underway because of the pressure of events later in the campaign.

On the other side of the valley, things were not greatly

better for the 2/4th Battalion. At 5.00 p.m., Dougherty got the orders from

Vasey to get out as best he could. This cheerful order followed several hours

fighting on the battalion’s front, which had left Dougherty’s B Company nearly

surrounded. The position here was similar to the problem faced by the 2/8th:

with a flank in the air, this time on the right, the battalion could not hold

its ground. Freed up by Vasey, Dougherty ordered that his right hold until dark

to allow the rest of the battalion to fall back. Earlier in the day, Dougherty

had wisely placed his carrier section in the rear of the battalion, where it

could do the most good in assisting in a withdrawal.

An order like this, to stand fast in the face of

overwhelming odds so that others may withdraw, is a desperate one, and it fell

to Dougherty’s B Company to comply with it. Their hard and selfless work done,

the men of B Company were eventually released to attempt their own escape. The

story of Private ‘Dasher’ Deacon exemplifies the courage required. Holding on

until virtually surrounded, Deacon lived up to his nickname, performing what he

called a ‘Stawell Gift’ (a famous Australian foot race) up the forward slope,

under artillery fire as he went. On the reverse slope, the Germans — with ‘Teutonic

efficiency’, he caustically wrote — barred the way with mortar fire: a bomb

fell between Deacon and two mates, killing the latter and blowing off Deacon’s

boot. Staggering back, dazed and barefoot in the bitter cold, Deacon stumbled

in the dark upon some of the battalion’s well-placed Bren-gun carriers, one of

them occupied by Dougherty himself. Hauled aboard with his commander, Deacon

recalled after the war that Dougherty’s help at this stressful moment had left

a lighter legacy: ‘Why even today, when I see an unemployed Lieutenant Colonel

walking, I always give him a lift!’ Unfortunately, Dougherty could not be

everywhere at once, and only 49 of B Company’s 130 men answered rollcall that

night.

As the dazed and disheartened Australian infantry stumbled

to the south, the Leibstandarte celebrated taking the pass, but it was a

victory that came at a cost. Witt’s Kampfgruppe saw 37 men killed and 95

wounded, and the Germans thought enough of the battle to award their highest

decoration for valour, the Knight’s Cross, to Obersturmfuhrer Gert Pleiss, who

led the final assault on the 2/8th.

Whatever the German casualty list, Mackay Force was

devastated. Included in its losses were a further ten two-pound guns and 80 men

of the 2/1st Anti-Tank Regiment, captured when the commanding officer of the

column ignored Dougherty’s advice and attempted to retreat down the line of the

railway, where the Germans were waiting. The senior staff officer of the 6th

Division, Colonel R. B. Sutherland, went forward to assess the situation and

reported at 10.00 p.m. on 12 April that the retiring motor transport of the 19

Brigade was in a state of disarray: he sought to re-establish order at Kozani

by diverting the trucks west onto the ground allotted to the brigade in the withdrawal

plans. The Greeks, however, were unimpressed by the work of the Mackay Force,

Papagos complaining that its withdrawal, without (in his view) serious

fighting, exposed the flank of the Greek 20 Division in the west.

Further forward, Vasey rallied his troops on a stop line

along the ridge just south of Sotire, where the remaining company of the

Rangers and two companies of the 2/4th received the support of the 1st Armoured

Brigade. At dawn on 13 April, the SS were dug in 1000 yards from the Australian

positions, and a fire-fight broke out immediately. Vasey, performing one of the

battlefield reconnaissances that would make him a deeply popular commander, was

caught in no-man’s-land. Dressed in a white raincoat, the Australian brigadier

must have made a tempting target: Vasey scrambled out on hands and knees.

Also caught in no-man’s-land were over 100 Australian,

British, Greek, and New Zealand prisoners who had been taken by the Germans

during the night. Some were killed, and more than 30 others wounded in this

exchange, before a further German attack went in against the Rangers on the

left of the Allied line at 7.30 a.m. What was left of the English battalion was

rescued by the intervention of the cruiser tanks of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment

(RTR), which held the ground while the infantry got away.

The RAF attempted to disrupt the German pursuit, but was

unable to repeat its success on the roads approaching Vevi three days before.

As RAF bomber crews found, to their cost, with airfields now further forward,

the Germans were in a better position to maintain air superiority over the

battlefield. Thus, as it ran in to attack a German column near Florina, an

entire formation of six Bristol Blenheim bombers was shot down by Bf 109

fighters of 6 Staffeln, Jagdgeschwader 27. The Germans also maintained constant

bombing and strafing raids on the British aerodromes, especially the northern

most airfield at Larisa, and these operations succeeded by mid-April in

reducing RAF strength to just 26 Blenheims, 18 Hurricanes, 12 Gladiator

biplanes, and five Lysander army cooperation aircraft.

With British air support failing, the 19 Brigade and the 1st

Armoured Brigade fell back to a second stop line south of Ptolemais, but the

Germans caught up with them again by 2.30 p.m. By then, the German pursuit was

the responsibility of the 9th Panzer Division, the Leibstandarte having been

ordered by Stumme to the west to cut off the retreat of Greek forces falling

back from the Albanian front. Faced by the British armour south of Ptolemais,

the division’s 33 Panzer Regiment pressed home its attack immediately, moving

through swampland on the left of the British, hoping to catch the tanks of

Charrington’s 1st Armoured Brigade in the rear. Again, the cross-country

performance of the German armour was excellent, and even though seven of the

panzers became bogged, the rest of the regiment emerged to fight a sharp tank

battle with the 3rd Royal Tanks and the 4th Hussars around the village of

Mavropiye.

The action was short but bitter. British anti-tank gunners

claimed to have destroyed eight panzers, and the 3rd RTR thought they had

accounted for five more. But as the battle reached a climax, Charrington found

himself without a reserve with which to counter-attack, having made a cardinal

sin before the battle. Lacking armoured cars with which to conduct

reconnaissance patrols prior to the battle, Charrington split up his tanks,

sending the 7 cruiser tanks of his headquarters troop to the New Zealand

Division, in exchange for some of the Kiwi’s Marmon Harrington armoured cars.

This division of the available tank fleet was a bad mistake, since the first

principle of armoured warfare is concentration, and Charrington’s decision to

split up his tanks again underlined British shortcomings in the way they

handled what armour they had in Greece.

Charrington and his men now paid the price for this error,

unable to meet the out-flanking advance of the German panzers. With the enemy

just a few hundred yards from brigade headquarters, the unit’s war diarist

later recorded with some understatement, ‘the lack of the protective troop

[that is, the tanks exchanged with the New Zealanders for armoured cars]

was

very sorely felt …’ One of Charrington’s senior officers, Major R. W. Hobson,

found a British cruiser tank withdraw into a position close by:

Up to now I had been unable to see anything, so I went down

to the tank — whose commander I knew — and asked where the enemy were. ‘Just

over there, about 300 yards away,’ he said; ‘and I don’t think it’s very

healthy for you on your feet.’ Almost at that moment something whizzed and the

ground was torn up just in front of my feet. Moments later that tank received a

direct hit and burst into flames.

Under cover of sacrifices of this kind, Charrington quickly

withdrew his headquarters, but the rapidity with which the British brigade left

the battlefield caused its greatest losses, because vehicles broken down due to

their poor mechanical reliability had to be destroyed: the 33rd Panzer Regiment

reported 21 British tanks set ablaze by their crews. By the end of the day, the

1st Armoured Brigade was down to the strength of a weak squadron, and the only

Allied tank force in Greece was effectively no more.

When men fight and die in wars, many more are horribly

wounded. Once the Greek campaign began for the Anzacs at Vevi, that reality

became clear to Mollie Edwards, who was back with the 2/5th AGH at Ekali. As

the first casualties of the new campaign were ferried back to the hospital, she

found peacetime medical procedures radically transformed by necessity. Medical

staff performed their own sterilisations, using kerosene tins and a primus, and

eventually made their own dressings as well. In normal times, nurses waited

patiently while doctors prescribed drugs such as morphia; but, at Ekali, these

demarcations evaporated overnight. Edwards was given a vial of morphia and a

syringe, and told to get on with it. Writing out doses in red pen on tape, and

sticking these on the foreheads of patients, Edwards was soon tending to 50

patients on a night shift, doing what she could for young men mangled in combat

— ‘Many a time I held their hands while they died.’

Edwards had more work than she might otherwise have faced

because of leadership failures in the days leading up to Vevi. Maitland Wilson

was one of the traditionalists in the British army who derided the theories of

armoured warfare advocated by Percy Hobart. He and Wavell had already paid one

half of the account for dismantling their armoured formations, when Rommel

gobbled up the dismembered 2nd Armoured Division in the desert on 8 April; at

Vevi, they paid the balance. The basic error in splitting the 2nd Armoured was

then compounded by the way Wilson handled his available tanks in the days

leading up to Vevi, where his ignorance of armoured warfare showed all too

clearly. The most precious commodity available to him — the all-arms 1st

Armoured Brigade — was despatched to the extremity of the Allied line, and then

broken up, its infantry and artillery detached from it, and the tanks left to

operate in the old-fashioned role of a cavalry screen. This ensured that the

force at Vevi was beaten in detail. At the first decisive engagement on 12

April, Vasey was routed for the want of armoured support. The pattern was repeated

on the next day, only in the reverse, when the British tanks fought with little

infantry or artillery support. Even a small number of tanks at Vevi operating

behind an infantry and artillery screen would have allowed the 2/4th and 2/8th

battalions to withdraw down the pass road, rather than face a cross-country

retreat, pursued by fresher SS infantry and the deadly assault guns.

It was clear from the presence of German armour around Vevi

on 11 April that the attack would be led by armoured vehicles but, on the

crucial day, the available allied armour was at Amindaion, well behind the

vital ground. Once again, as in France a year earlier, the British had failed

to coordinate their forces in a way that brought a combined force into action

at the decisive point.

Mackay, who was eventually given command of 1st Armoured

Brigade as it fell back, had little experience in armoured warfare, like most

of the Australian commanders at that time. He failed to get tank support

forward to Vasey, perhaps because both the 19 Brigade and his own headquarters

took such a benign view of the fighting for most of the day.

Admittedly, the Greek campaign was strategically flawed from

the start, and was then further compromised by the commanding officers’

inability to face the inevitable loss of Thrace and to pull all remaining

forces back to a central line that might be held, at least for some time.

Wilson’s efforts, however, ensured that the campaign quickly degenerated into a

rout, leaving the rear echelons of his army open to dislocation and loss. On

the Vermion–Olympus Line, Wilson needed to follow the line of thinking that

allowed the Australian general, Lavarack, to hold Tobruk when Rommel first

assaulted it on 14 April, just days after Vevi. At that battle, Lavarack decisively

stopped a German tank attack for the first time in the war, and he did so with

infantry supported by a strong gun line, with his limited armour operating

behind those defences to contain any breakthrough. Applied to Greece, these

tactics would have seen the 1st Armoured Brigade operating as an integrated

formation, behind the mountain passes held by infantry and artillery around

Mount Olympus. Wilson’s handling of the 1st Armoured Brigade was but the latest

rendition of a common British saga in the first half of the conflict — the

persistent failure of British generals to handle tank forces with any

sophistication or success, mainly because they defied the principles of

concentration and all-arms cooperation.

At Vevi, the victims of this ineptitude were the

long-suffering infantry. However, Mackay, the commanding officer of the 6th

Division, was unimpressed by the showing of his units. Admittedly, he thought

the anti-tank guns were sited too far forward, but he wrote critically that the

Australians were not sufficiently trained to deal with German infiltration, and

that ‘[i]n some cases the inf [infantry] did NOT show that essential

determination to stay and fight it out when the enemy did filter around their

flanks’. These drives around the flanks meant that ‘a few local successes by

the enemy immediately rendered localities on either flank untenable for the

enemy was too quick to reinforce these successes’.

Mackay had less to say about the lack of Allied armour at

Vevi, and his own failure to get British tanks forward to help his infantry.

Overrun by the Leibstandarte, the Australian 2/4th and 2/8th battalions were

temporarily disabled as effective military formations. The later careers of the

battalion commanders reflected their relative performance at Vevi — 34-year-old

Dougherty was promoted to command a brigade in 1942, and led the 21 Infantry

Brigade to the end of the war. In contrast, 50-year-old Mitchell was the oldest

battalion commander in the AIF. The Australian army had set an age limit of 45

for battalion leaders, but Mitchell had pulled enough strings to escape the

prohibition. However, his showing at Vevi validated the original wisdom of an

upper-age limit — he was relieved of his command and relegated to lead a

recruit-training centre for the rest of the war.

With the Mackay Force streaming back from Vevi in tatters,

the door to central Greece was open. The Allied commanders now faced the

prospect that their forward positions on the right, to the north of Mount

Olympus, would be turned, and their whole force encircled. Much now would

depend on the staying power of the Anzac infantry, who had to withdraw across

snow-covered mountain passes, harried by the German air force.