P11 VERSUS THE LUFTWAFFE

During the summer of 1939 the Polish air force found itself dealing with repeated violations of its airspace by photoreconnaissance Do17s of the Luftwaffe, and the experience of the P11c, the principal Polish fighter, was not encouraging. Unable to reach either the speeds or the altitudes of the German intruders, the P11c was clearly obsolescent by this time, and the intruders were able to evade the Polish fighters’ attempted interceptions virtually at will. In preparation for the conflict which by this stage was widely anticipated, the Polish Air Force had been reorganized in the spring, with around a third of the available fighters concentrated around Warsaw and the remainder allocated to the various armies. By the end of August most of the operational aircraft had been dispersed to concealed airfields in preparation for the assault, which duly began before dawn on September 1. Because of heavy fog on the opening day of the war, German plans were changed, with the intended mass attack on Warsaw postponed in preference to raids against airfields and other tactical targets. Flying low to locate the airfields, the bombers of Luftflotte 4, allocated to the advance against Kracow in the south, gave the defending fighters a chance at interception.

Built by the Pánstwowe Zaklady Lotnicze (National Aviation Establishment) and first flying in August 1931, the PZL P.11 was the descendant of a series of clean monoplanes designed by Zygmunt Pulawski, incorporating a unique gull wing that was thickest near the point where four faired steel struts buttressed it from the fuselage sides. When the first PZL P.1 flew on September 26, 1929, it thrust Poland to the forefront of progressive fighter design. In 1933 Poland’s air force, the Lotnictwo Wojskowe, became the first in the world to be fully equipped with all-metal monoplane fighters as the improved P.6 and P.7 equipped its eskadry. When the production P.11c, powered by a 645-horsepower Škoda-built Bristol Mercury VI S2 nine-cylinder radial engine, entered service in early 1935, it still rated as a modern fighter, with a maximum speed of 242 miles per hour at 18,045 feet and a potent armament of four 7.7mm KM Wz 33 machine guns, although its open cockpit and fixed landing gear were soon to become outdated. By 1939 the P.11c was clearly obsolete, and efforts were already under way to develop a successor to replace it within the year. Poland did not have a year, however—on September 1, time ran out as German forces surged over her borders.

A morning fog over northern Poland thwarted the first German air operation, as Obltn. Bruno Dilley led three Junkers Ju 87B-1 Stukas of 3rd Staffel, Sturzkampfgeschwader 1 (3./StG 1) into the air at 0426, flew over the border from East Prussia and at 0434—eleven minutes before Germany formally declared war—attacked selected detonation points in an attempt to prevent the destruction of two railroad bridges on the Vistula River. The German attack failed to achieve its goal and the Poles blew up the bridges, denying German forces in East Prussia an easy entry into Tszew (Dirschau). The “fog of war” also handicapped a follow-up attack on Tszew by Dornier Do 17Z bombers of III Gruppe, Kampfgeschwader 3 (III./KG 3).

Weather conditions were better to the west, allowing Luftflotte 4 to dispatch sixty Heinkel He 111s of KG 4, Ju 87Bs of I./StG 2, and Do 17Es of KG 77 on a series of more effective strikes against Polish air bases near Kraków at about 0530, Rakowice field being the hardest hit. Assigned to escort the Heinkels was a squadron equipped with a new fighter of which Luftwaffe Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring expected great things: the Messerschmitt Me 110C-1 strategic fighter, or Zerstörer.

The Me 110 had evolved from a concept that had been explored during World War I but which was only put into successful practice by the French with their Caudron 11.A3, a twin-engine, three-seat reconnaissance plane employed as an escort fighter in 1918. The strategic fighter idea was revived in 1934 with the development of the Polish PZL P.38 Wilk (Wolf), which inspired a variety of similar twin-engine fighter designs in France, Germany, Britain, the Netherlands, Japan, and the United States.

Göring was particularly enthralled by what he dubbed the Kampfzerstörer (battle destroyer), and in 1934 he issued a specification for a heavily armed twin-engine multipurpose fighter capable of escorting bombers, establishing air superiority deep in enemy territory, carrying out ground-attack missions, and intercepting enemy bombers. BFW, Focke-Wulf, and Henschel submitted design proposals; but it was Willy Messerschmitt’s sleek BFW Bf 110, which ignored the bombing requirement to concentrate on speed and cannon armament, that won out over the Fw 57 and the Hs 124. Powered by two Daimler Benz DB 600A engines, the Bf 110V1 was first flown by Rudolf Opitz on May 12, 1936, and attained a speed of 314 miles per hour, but the unreliability of its engines required a change to 680-horsepower Junkers Jumo 210Da engines when the preproduction Bf 110A-0 was completed in August 1937.

Although more sluggish than single-seat fighters, the Bf 110A-0 was fast for a twin-engine plane, and its armament of four nose-mounted 7.9mm MG 17 machine guns and one flexible 7.9mm MG 15 gun aft was considered impressive. Prospective Zerstörer pilots were convinced that tactics could be devised to maximize its strengths and minimize its shortcomings, just as the British had done with the Bristol fighter in 1917. The Bf 110B-1, which entered production in March 1938, was even more promising, with a more aerodynamically refined nose section housing a pair of 20mm MG FF cannon. Later, in 1938, the 1,100-horsepower DB 601A-1 engine was finally certified for installation, and in January 1939 the first Messerschmitt Me 110C-1s, powered by the DB 601A-1s and bearing a new prefix to mark Willy Messerschmitt’s acquisition of BFW, entered service. By September 1, a total of eighty-two Me 110s were operating with I Gruppe (Zerstörer) of Lehrgeschwader (Operational Training Wing) 1 (I(Z)./LG 1) commanded by Maj. Walter Grabmann, and I Gruppe, Zerstörergeschwader 1 (I./ZG 1) under Maj. Joachim-Friedrich Huth, both assigned to Luftflotte 1; and with I./ZG 76 led by Hptmn. Günther Reinecke, attached to Luftflotte 4 along the Polish-Czechoslovakian border.

Intensely trained for their multiple tasks, the Zerstörer pilots, like those flying the Stuka, had been indoctrinated to think of themselves as an elite force. Therefore, the Me 110C-1 crewmen of the 2nd Staffel of ZG 76 were as eager as Göring himself to see their mettle tested as they took off at 0600 hours to escort KG 4’s He 111s. To the Germans’ surprise and disappointment, they encountered no opposition over Kraków.

During the return flight, 2./ZG 76’s Staffelführer, Obltn. Wolfgang Falck, spotted a lone Heinkel He 46 army reconnaissance plane and flew down to offer it protection, only to be fired at by its nervous gunner. Minutes later Falck encountered another plane, which he identified as a PZL P.23 light bomber. “As I tried to gain some height he curved into the sun and as he did I caught a glimpse of red on his wing,” Falck recalled. “As I turned into him I opened fire, but fortunately, my marksmanship was no better than the reconnaissance gunner’s had been, [for] as he banked to get away I saw it was a Stuka. I then realized that what I had thought was a red Polish insignia was actually a red E. I reported this immediately after landing and before long the colored letters on wings of our aircraft were overpainted in black.”

As the Stukas of I./StG 2 were returning from their strike, they passed over Balice airfield just as PZL fighters of the III/2 Dywizjon (121st and 122nd Eskadry), attached to the Army of Kraków, were taking off. By sheer chance one of the Stuka pilots, Ltn. Frank Neubert, found himself in position to get a burst from his wing guns into the leading P.11c’s cockpit, after which he reported that it “suddenly explode[d] in mid-air, bursting apart like a huge fireball—the fragments literally flew around our ears.” Neubert’s Stuka had scored the first air-to-air victory of World War II—and killed the commander of the III/2 Dyon, Kapitan Mieczyslaw Medwecki.

Medwecki’s wingman, Porucznik (Lieutenant) Wladyslaw Gnys of the 121st Eskadra, was more fortunate, managing to evade the bombs and bullets of the oncoming trio of Stukas and get clear of his beleaguered airfield. Minutes later, he encountered two returning Do 17Es of KG 77 over Olkusz and attacked. One went down in the village of Zurada, south of Olkusz, and Gnys was subsequently credited with the first Allied aerial victory of World War II. Shortly afterward, the wreckage of the other Do 17E was also found at Zurada and confirmed as Gnys’s second victory. None of the German bomber crewmen survived.

In spite of the adverse weather that had spoiled its first missions, Luftflotte 1 launched more bombing raids from East Prussia, including a probing attack on Okacie airfield outside Warsaw by sixty He 111Ps of Lehrgeschwader 1, escorted by Me 110Cs of the wing’s Zerstörergruppe, I(Z)./LG 1. As the Heinkels neared their target, the Polish Brygada Poscigowa (Pursuit Brigade), on alert since dawn, was warned of the Germans’ approach by its observation posts, and at 0650 it ordered thirty PZL P.11s and P.7s of the 111th, 112th, 113th, and 114th Eskadry up from their airfields at Zielonka and Poniatów to intercept. Minutes later, the Poles encountered scattered German formations and waded in, with Kapral (Corporal) Andrzej Niewiara and Porucznik Aleksander Gabszewicz sharing in the destruction of the first He 111. Over the next hour, the air battle took the form of numerous individual duels, during which Kapitan Adam Kowalczyk, commander of the IV/I Dyon, downed a Heinkel, and Porucznik Hieronim Dudwal of the 113th Eskadra destroyed another.

The Me 110s pounced on the PZLs, but the Zerstörer pilots found their nimble quarry to be most elusive targets. Podporucznik (Sub-Lieutenant) Jerzy Palusinski of the 111th Eskadra turned the tables on one of the Zerstörer and sent it out of the fight in a damaged state. Its wounded pilot was Maj. Walter Grabmann, a Spanish Civil War veteran of the Legion Condor and now commander of I(Z)./LG 1.

In all, the Poles claimed six He 111s, while the German bombers were credited with four PZLs; their gunners had in fact brought down three. Once again, Göring’s vaunted Zerstörer crews returned to base empty handed. When the Germans sent reconnaissance planes over the area to assess the bombing results at about noon, Porucznik Stefan Okrzeja of the 112th Eskadra caught one of the Do 17s and shot it down over the Warsaw suburbs.

As the weather improved, Luftflotte 1 struck again in even greater force, as two hundred bombers attacked Okecie, Mokotow, Goclaw, and bridges across the Vistula. They were met by thirty P. 11s and P.7s of the Brygada Poscigowa, which claimed two He 111Ps of KG 27, a Do 17, and a Ju 87 before the escorting Me 110Cs of I(Z)./LG 1 descended on them. This time the Zerstörer finally drew blood, claiming five PZLs without loss, and indeed the Poles lost five of their elderly PZL P.7s. One Me 110 victim, Porucznik Feliks Szyszka, reported that the Germans attacked him as he parachuted to earth, putting seventeen bullets in his leg. The Me 110s also damaged the P.11c of Hieronim Dudwal, who landed with the fuselage just aft of the cockpit badly shot-up; two bare metal plates were crudely fixed in place over the damaged area, but the plane was still not fully airworthy when the Germans overran his airfield.

For most of September 1, the Me 109s were confined to a defensive posture, save for a few strafing sorties. For the second bombing mission in the Warsaw area, however, I. Gruppe of Jagdgeschwader 21 was ordered to take off from its forward field at Arys-Rostken and escort KG 27’s He 111s. The Me 109s rendezvoused with the bombers, only to be fired upon by their gunners. When the Gruppenkommandeur (Group Commander), Hptmn. Martin Mettig, tried to fire a recognition flare, it malfunctioned, filling his cockpit with red and white fragments. Mettig, blinded and wounded in the hand and thigh, jettisoned his canopy—which broke off his radio mast—and turned back. Most of Mettig’s pilots saw him head for base, and being unable to communicate with him by radio, they followed him. Only upon landing did they learn what had happened.

Not all of the Gruppe had seen Mettig, however, and those pilots who continued the mission were rewarded by encountering a group of PZL fighters. In the wild dogfight that followed, the Germans claimed four of the P.11cs, including the first victory of an eventual ninety-eight by Ltn. Gustav Rödel. The Poles claimed five Me 109s, including one each credited to Podporuczniki Jerzy Radomski and Jan Borowski of the 113th Eskadra, and one to Kapitan Gustaw Sidorowicz of the 111th. Podpolkovnik (Lieutenant Colonel) Leopold Pamula, already credited with an He 111P and a Ju 87B earlier that day, rammed one of the German fighters and then bailed out safely. Porucznik Gabszewicz was shot down by an Me 109 and, like Szyszka, subsequently claimed that the Germans had fired at him while he parachuted down.

In addition to challenging the waves of German bombers and escorts that would ultimately overwhelm them, PZL pilots took a toll on the army cooperation aircraft which were performing reconnaissance missions for the advancing panzer divisions. Podporucznik Waclaw S. Król of the 121st Eskadra downed a Henschel Hs 126, while Kapral Jan Kremski shared in the destruction of another. After taking off on their second mission of the day to intercept a reported Do 17 formation at 1521 hours, Porucznik Marian Pisarek and Kapral Benedykt Mielczynski of the 141st Eskadra spotted an Hs 126 of 3.(H)/21 (3 Staffel (Heeres), Aufklärungsgruppe 21, or 3rd Squadron Army of Reconnaissance Group 21), attacked it and sent it crashing to earth near Torun. The pilot, Obltn. Friedrich Wimmer, and his observer, Obltn. Siegfried von Heymann, were both wounded. Shortly afterward, two more P.11cs from their sister unit, the 142nd Eskadra, flew over the downed Henschel, and one of the Poles, Porucznik Stanislaw Skalski, later described what occurred when he landed nearby to recover maps and other information from the cockpit:

The pilot, Friedrich Wimmer, was slightly wounded in the leg; his navigator, whose name was von Heymann, had nine bullets in his back and shoulder. I did what I could for them and stayed with them until an ambulance came. The prisoners were transferred to Warsaw. After the Soviet Union invaded Poland on 17 September, they became prisoners of the Russians, but were released at the end of October. When they were interrogated by the highest Luftwaffe authorities, Wimmer told them of my generosity. The Germans, who later learned that I had gone to Britain to fight on, said if I should become their prisoner, I would be honored very highly.

The observer, von Heymann, died in 1988. . . . I tried to get in touch with the pilot for three years. The British air attaché and Luftwaffe archives helped me to contact Colonel Wimmer. I went to Bonn to meet him in March 1990, and the German ace Adolf Galland also came over at that time. In 1993, Polish television went with me, to make a film with Wimmer. Reporters asked why I did it—why I landed and helped the enemy, exposing my fighter and myself to enemy air attack. I was young, stupid and lucky. That is always my answer!

I came back late in the afternoon and I had to land on the road close to a forest—Torun aerodrome had been bombed already. I then gave [General Dywizji Wladyslaw] Bortnowski, commander of the Armia Pomorze, the maps that I had captured from the Hs 126, which gave all the dispositions and attack plans of German divisions in Pomerania. He kissed me and said this was all the information his army needed.

On the following day, Skalski came head on at what he described as a “cannon-armed” Do 17 in a circling formation of nine and shot it down, then claimed a second bomber minutes later. Dorniers were not armed with cannon; but Me 110s were, and Skalski subsequently recalled that the Poles were completely unfamiliar with the Zerstörer—nobody had seen them in action until September 1. Moreover, I/ZG 1 lost a Bf 110B-1, its pilot, Hptmn. Adolf Gebhard Egon Claus-Wendelin, Freiherr von Müllenheim-Rechberg, commander of the 3rd Staffel, being killed, while his radioman, Gefreiter Hans Weng, bailed out and was taken prisoner of war (POW). Skalski’s “double” was the first of four and one shared victories with which he would be officially credited during the Polish campaign. Later, flying with the Royal Air Force, he would bring his total up to 18 1/2, making him the highest-scoring Polish ace of the war.

Although Poland was overrun in three weeks, its air force occasionally put up a magnificent fight, though its efforts were rendered inconsistent by poor communications and coordination. Polish fighters were credited with 129 aerial victories for the loss of 114 planes, and many of the pilots who scored them would fight on in the French Armée de l’Air and the Royal Air Force.

The fall of Poland terminated the career of the PZL P.11c, but only marked the beginning for the Me 110, which, after a further run of success, finally met its nemesis in the form of the Hurricane and Spitfire. Relegated to fighter-bomber and photoreconnaissance duties after the Battle of Britain, the Zerstörer would undergo a remarkably productive revival as a night fighter.

Poland’s main front-line fighter in September 1939 was the PZL P11c. Obsolete in comparison with the German Me109s, it nevertheless gave a good account of itself before Poland fell.

Poland was first in the firing line. Early in the morning of September 1 a force of about 120 Heinkel He111s and Dornier Do17s, escorted by Messerschmitt Bf110 fighters, were reported by Polish ground observation posts to be heading for Warsaw. The Luftwaffe had made giant strides since the first German pilots went into action with the Condor Legion in 1936. It now possessed 3652 first-line aircraft comprising 1180 medium twin-engined bombers (mostly He111s and Do17s), 366 Stuka dive bombers, 1179 Me109 and Me110 fighters, 887 reconnaissance aircraft and 40 obsolescent ground-attack Hs123s. Transport was provided by 552 Ju52s, and there were 240 naval aircraft of various types. For the Polish campaign the Luftwaffe deployed 1581 of these aircraft.

German intelligence had estimated the front¬ line strength of the Polish air force at some 900 aircraft. In fact on 1 September the figure was nearer 300, made up of 36 P37 `Los’ twin-engined medium bombers, 118 single-engined `Karas’ P23 light reconnaissance bombers and 159 fighters of the PZL P11c and P7 types. Light gull-winged monoplanes, with open cockpits and fixed undercarriages, they had been an advanced design in the early 1930s but were now hopelessly outclassed by the Luftwaffe’s modern aircraft. Neither the PZL P11c nor the P7 could get high enough to intercept the high-flying Do17 reconnaissance aircraft.

On the opening day of hostilities, however, the German attack came in at low level, aiming to knock out the Polish air force on the ground. The Luftwaffe failed to achieve its objective as during the last days of peace the Polish air force had dispersed its aircraft to a number of secret airfields. On the morning of September 1 not one Polish squadron remained at its pre-war base. As a result only 28 obsolete or unserviceable machines were destroyed at Rakowice air base.

The first air combat of WW2 took place during this action when Captain M Medwecki, commanding officer of III/2 Fighter `Dyon’ was shot down by a Ju87 soon after he took off. Another pilot, Lieutenant W Gnys attacked the Ju87 and later shot down two low-flying Dornier 17s – the first Polish kills. Warsaw too was attacked by Luftwaffe bombers and the first to be shot down, a low-flying He111, was destroyed by Lieutenant A Gabszewicz.

A more spectacular victory occurred later that day during a running air battle above Warsaw. Second Lieutenant Leopold Pamula shot down a He111 and a Ju87 but ran out of ammunition when the fighter escort came down on the P11s. Pamula rammed one Me109 before parachuting to safety. In the same battle Aleksander Gabszewicz had his P11 set on fire and had to bale out. On his way to the ground he was shot at by a fighter, an event experienced by other parachuting Polish pilots as the battles continued.

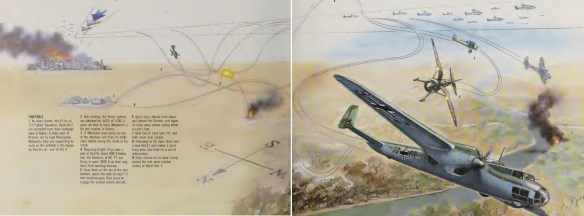

Despite the inferiority of the Polish fighters, they achieved at least a dozen victories on the first day of WW2, although they lost 10 fighters with another 24 damaged. This gave the Polish pilots some confidence. Even with their outmoded aircraft they seemed able to cope with the Germans. Their pilots found that one good method of attack was to dive head-on where a tail-chase was more or less out of the question. This collision-course tactic unnerved the German bomber pilots and was most effective in breaking up formations and inflicting damage on the Heinkels and Dorniers. The Polish fighter pilots unexpectedly found the twin-engined Me110s more dangerous than the single-engined Me109s. The first German kill of WW2 was in fact scored by a 110 pilot, Hauptmann Schlief, who shot down a P11 on September 1.

By mid-September German pincers from north and south had closed around Warsaw. Then on September 17 the Red Army intervened from the east, destroying the last Polish hopes. Warsaw surrendered on September 27 and the last organized resistance collapsed in the first week of October. Despite the obsolescent equipment of the Polish air force, and its inferiority in numbers, it had inflicted heavy damage on the Luftwaffe, which had lost 285 aircraft with almost the same number so badly damaged as to be virtually noneffective. Polish fighter pilots were officially credited with 126 victories, which indicates modest claiming by them, for Polish anti-aircraft fire claimed less than 90, leaving an unclaimed deficit of some 70 aircraft. The last German aircraft shot down by a Pole in this campaign was claimed on September 17 by Second Lieutenant Tadeusz Koc. The highest-scoring Polish pilot was Second Lieutenant Stanislaw Skalski, with 6 1/2 kills. The highest-scoring German, and Germany’s first `ace’ of WW2, was Hauptmann Hannes Gentzen, who scored seven victories in a Me109D.

A total of 327 aircraft were lost by the Polish Air Force. Of these 260 were due to either direct or indirect enemy action with around 70 in air-to-air fighting; 234 aircrew were either killed or reported missing in action. One of the chief lessons learned by the German bomber force operating over Poland (and as the RAF bombers were soon to discover) was that they were susceptible to fighter attack. The immediate requirement, therefore, was for the bombers to have heavier defensive armament and additional armor protection for their crews.

STANISLAW SKALSKI

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Stanislaw F Skalski was in his early 20s. and a regular Polish Air Force officer, flying PZL fighters with 142 Squadron. On the second day of the war, he destroyed two Dornier 17s, and by the end of the brief Polish campaign was the top-scoring fighter pilot with 6 1/2 victories. He escaped to England, and joined 501 Squadron RAF in the Battle of Britain, scoring four victories. In June 1941 he was made a flight commander in 306 Polish Squadron and shot down five more German aircraft. He received the British DFC, having already won the Polish Silver Cross and Cross of Valor. He then had a spell as an instructor before commanding 317 Squadron in April 1942, winning a bar to his DFC.

In 1943 he led a group of experienced Polish fighter pilots into the Middle East, flying Spitfire IXs attached to 145 RAF Squadron. This ‘Fighting Team’ or ‘Skalski’s Flying Circus’ as it was also called, operated during the final stages of the Tunisian campaign, Skalski adding three more personal kills. He was then given command of 601 Squadron – the first Pole to command an RAF fighter squadron. He received a second bar to his DFC as well as the Polish Gold Cross before returning to England.

As a Wing Commander in April 1944 he commanded 133 (Polish No 2) Fighter Wing, flying Mustangs, raising his score to 19 victories when he forced two FW190s to collide on June 24. He ended the war as a gunnery instructor, decorated additionally with the British DSO. Returning to Poland after the war he was imprisoned by the Russians; and, following his release, drove a taxi in Warsaw.