Nieuport-Delage

NiD-29

The immediate successor of the SPAD fighters in the French squadrons

after World War I. Although slower than the Wibault 1, it was preferred by the

French for its better control harmonization and efficiency.

An answer for a 1917 fighter program, the first of three

prototypes flew in 1918. Production models of the NiD-29C1 reached operational

units in 1922. Five years later, 620 had been delivered to the French air

force, and a total of more than 700 were produced for France until 1928. Only

three saw active service, used during one month in Morocco for bombing and strafing

against rebels.

The NiD-29C1 was a great export success. Spain bought 30,

Belgium 109, Italy 181 (including 175 produced under license), Sweden 10

(called J2), and Argentina and Siam unknown quantities. The most important

customer was Japan, with no less than 608 built as the Ko 4 between 1924 and

1932. It was the front-line fighter of the Japanese army for several years and

fought during the Japanese war against China. Some Ko 4s were still used for

training when Japan entered World War II. The NiD-29C1 is one of the very few

aircraft whose service life spanned both world wars. In its heyday in 1924, it

was considered by U. S. General Billy Mitchell to be the best pursuit plane of

the high-speed diving type in the world.

Hanriot HD-1

Belgium’s Aviation Militaire, dependent on British and

French sources of supply for its equipment and apparently undaunted by its

unfortunate experience with Dupont’s Ponnier L.I took advantage of the French

refusal to place an order for the HD-1, drawing up an initial contract for

twenty aircraft in June, 1917, It was the Belgian government’s desire to have

an aircraft manufacturer working directly for them, but when the first HD-1s

reached Belgium on August 22, 1917, it looked as though another mistake had

been made. The HD-1s were assigned to the lére Escadrille de Chasse to replace

the unit’s Nieuport XXIIIs, and HD-l No.1 was offered to Jean Olieslagers, who was

to be Belgium’s fifth ranking ace. Olieslagers immediately announced his

preference for the Nieuport, passing the unwanted HD-1 to Andre Demeulemeester.

Demeulemeester would not accept what Olieslagers had refused, and passed on the

HD-1 to his new wingman, Willy Coppens, who had just joined the lére

Escadrille. Coppens was delighted to exchange his old Nieuport XI (in which the

standard 80 h.p. engine had been supplanted by a 110 h.p. Le Rhône) for the new

Hanriot, and his report on the HD-I was highly enthusiastic. For awhile,

Demeulemeester and Coppens made an odd pair, the flight commander flying a

Nieuport and the wingman flying an Hanriot, but Demeulemeester and Olieslagers

soon admitted that they had misjudged the HD-1, although it was with some reluctance

that they adopted the new fighter in October, 1917.

The Hanriot HD-1 carried only one machine gun, and this was

mounted over the port side of the nose. This arrange- ment was, in the

viewpoint of the Belgian pilots, most unsatisfactory, and the HD-1s were

immediately returned to the Parc de l’Aviation Militaire Belge at Beaumarais in

France, where the gun was centralised on the fuselage. At the same time, the

pilot’s seat was reinforced and an attempt was made to fit the fighter with a

Nieuport-type tailskid. One of the HD-1s was tested with an experimental 150

h.p. Le Rhone engine, but this proved unsatisfactory. Both Demeulemeester and

Coppens considered the HD-1 to be under-armed, desiring a fighter with twin

machine guns. Demeulemeester actually had a pair of guns fitted to his machine,

but reverted to the single gun arrangement when he found that the extra gun had

an adverse effect on the HD-1 ‘s ceiling.

In view of the limited enthusiasm with which the HD-1 had

been greeted upon its arrival in Belgium, the Command proposed its replacement

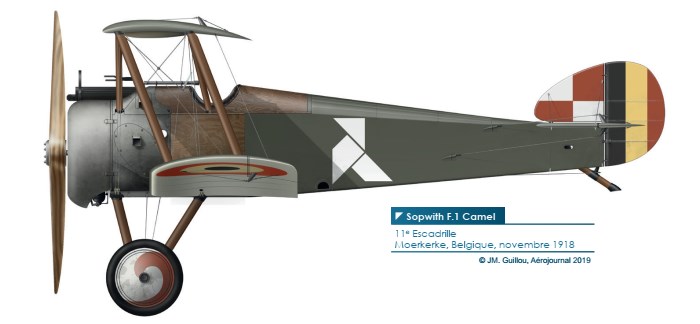

with the Sopwith Camel at the beginning of January, 1918. The Camel, with its

130 h.p. Clerget engine, lacked the extreme maneuverability and delicacy of

handling which characterised the Hanriot. Belgian pilots found that the Camel

could be dangerous during aerobatics and that visibility from the cockpit left

something to be desired. Thus, by the end of January, the camels were quietly

transferred to the new 1léme Escadrille and the HD-1 was finally accepted as

standard equipment and the 1 ére Escadrille never had cause to regret its

choice.

In August, 1917, the 5éme Escadrille had received the

splendid new SPAD S.XIII, but despite the tremendous reputation of this fighter

and that of the redoubtable Sopwith Camel, by October, 1918, all three Belgian

fighter squadrons had standardised on the nimble little Hanriot HD-1.

Willy Coppens, who had been enraptured by the little scout

from the outset and was to become the Hanriot’s greatest exponent and Belgium’s

leading ace, used several HD-1s until October 14, 1918, when he was hit by

shrapnel while attacking an observation balloon and seriously injured in the

ensuing crash landing. Initially he flew HD-1 No.1, but from October 26, 1917,

he flew HD-1 No.9, which had the centrally-mounted machine gun. When that

aircraft was damaged on January 19, 1918, he exchanged it for No.17, which he

later fitted with a 0.303-in. Vickers gun, and on May 3, 1918, he received yet

another Hanriot, the HD-1 No.24. In addition to this aircraft, Coppens flew

Nos. 6 and 23, the latter having a Lanser fireproof fuel tank which was a

personal gift of Rene Hanriot. His last HD-I was No.45,which had two 0.303-in.

Vickers guns.

In all, seventy-nine HD-1s were built for Belgium, and some of these were still flying in 1926 with the 7éme Escadrille de # Chasse at Nivelles, alongside the Nieuport 29C.1 fighters fitted with 300 h.p. Hispano-Suiza engines

#

Belgium’s small size, limited resources and intention to

remain neutral in any conflict, all led to meagre beginnings for the Belgian

Air Service – the Aviation Militaire Belge (AMB). Despite this, King Albert was

very air minded, and although never a pilot himself, he was flown several times

over the lines during the course of the war, although occasionally the pilot

responsible had to pretend to misunderstand his requests to go deeper into

German Occupied territory!

It was King Albert who had encouraged the setting up of the

Military Aviation School in 1911, although its original establishment stood at

just five pilots, two mechanics and one carpenter, but no aircraft. And it was

the King who presented the school with its first aircraft, when he handed over

to them a machine which had been given to him as a gift by Baron de Caters.

Perhaps it is natural that any small organization will have

its share of individualists, and the AMB seems to have had more than its fair

share of innovators. In September 1912, Belgium became the first European

country to fit a machine gun to an aeroplane and fire at a ground target (a

sheet). The same crew travelled to England in November to repeat the

demonstration at Hendon, then at Aldershot, for the benefit of the British Army.

Their favourable reception contrasted with the original demonstration in

Belgium when they had been castigated for damaging the sheet!

By 1914, there had been some expansion, as four squadrons

existed. This increase was not as great as it might seem, however, as each

squadron numbered just four Henri Farmans, flown by five pilots and six

observers. Ground equipment consisted of five lorries, one for each squadron

and another used as a workshop. So at the outbreak of the war, the AMB was

nothing if not compact and highly mobile.

Belgium had a small aircraft factory which after the

occupation became the Military Workshop or depot in Calais. As a result

throughout the war the AMB was reliant on the French, and, to a lesser extent,

on the British to provide its machines. As a result it tended to be given

surplus and obsolescent aircraft by its allies, which makes the achievements of

its aces all the more remarkable.

The aircraft supply situation was not helped either by the

weather. Most of the AMB’s aircraft were destroyed on the ground by a violent

storm on 13 September 1914, and every one of its aircraft was lost in a

hurricane on 28 December. On a day to day basis the weather along the coast was

perhaps the worst anywhere on the Western Front, and between February 1915 and

November 1918 on 432 out of 1380 days the weather was too bad for any

operations to take place at all.

For reasons of limited range and patriotism, most of the

operations of the AMB were conducted from airfields squeezed into the small portion

of Belgium still unoccupied by the Germans. The natural aggression of the

pilots, trying to avenge the invasion of their country, had to be tempered with

their being such a small number of them that the loss of just one or two would

cause significant difference to the crew establishment. The prevailing westerly

winds, the bane of Allied pilots, drifted any combat eastwards deeper behind

German lines, so prolonged combats were not encouraged. And even if combats

were successful, unless the German aircraft came down in Allied territory, or

near enough to the front lines to be observed by Allied troops, victory claims

were hard to establish.

In February 1916 the first dedicated fighter squadron was

formed when Escadrille I became the 1ère Escadrille de Chasse equipped with

French Nieuport scouts. However, aeroplanes were never numerous and in January

1917 the AMB only had thirty-nine machines available. They eventually received

more modern equipment from their allies, such as Spads and Sopwith Camels but they

were in small numbers. By March 1918 the AMB had increased to twelve

escadrilles of which one was a maintenance unit and another operated seaplanes.

One of the escadrilles, though, still had Farmans, which had been condemned as

operationally obsolete by the British in 1915.

One complication for those personnel operating from the

airfield at Houthem was that squeezed into the same tiny village were the

Belgian royal family, and the headquarters of the Belgian army. So every move

was made under the gaze of the highest echelons of the powers-that-be.

A further by-product of the AMB’s small size was that it

often fought alongside units belonging to its Allies, most commonly squadrons

of the RNAS. But this in itself could be a mixed blessing as 4 Naval, perhaps

the most active unit in Flanders, on more than one occasion attacked Belgian

aircraft and forced them down. Fortunately, no Belgian fighter pilots were

seriously wounded during these encounters.

Though small the AMB was an efficient and effective force and

produced a number of aces, including Willy Coppens, who was the highest scoring

kite balloon ace of any nation. Their skill flying obsolescent machines is

demonstrated by the fact that all their aces survived the war.

Houthem Aerodrome

After their occupation by the Germans the Belgians were left

with just a tiny corner of their country. For nearly four years the village of

Houthem became the capital of free Belgium and as such was a heaving scene of

activity. The headquarters of the Belgian army was on the edge of the aerodrome

and King Albert and the royal family lived nearby. The front line was only

seventeen kilometres to the east and the French border three kilometres to the

west.

Following the end of the ‘Race to the Sea’ towards the end

of 1914, the front line remained in virtually the same place in the few miles

near the coast until the final advance to victory in 1918. As a result the

squadrons of the AMB tended to remain at the same airfields through the course

of the war, not being moved about by the ebb and flow of the war. It was only

during the ‘last hundred days’ that it was able to help in the final advance of

the Allies, commanded in Belgium by King Albert who had been so instrumental in

encouraging its formation just a few years before.

The fact the aerodrome was so close to the French frontier

was a bonus as the Belgians would take a big-bellied Farman F40 to the French

aerodrome at Hondschoote and load up with crates of alcohol for the squadron,

which was in contravention of orders from High Command!

The initial aerodromes employed by the AMB once the front

line had stabilised were Coxyde/Furnes (page 123) where I, II and III

Escadrilles were based, and Houthem where the IV and V Escadrilles were

established. There was also a seaplane unit at Calais.

Willy Coppens, Belgium’s highest scoring ace, after

completing his pilot training at Étampes, in early 1916 was posted to 6me

Escadrille at Houthem where he was to fly the Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c. He

described his arrival in his book Days on the Wing:

Leaving my kit in the

station, I climbed on to a lorry proceeding in the direction of Houthem.

Travelling thus, I covered that long, straight road, bordered on either side by

willow trees, past an endless succession of low-lying meadows, separated by

endless dykes. My lorry deposited me at some distance from the village. A very

severe spell of weather had set in, and the country was deep in snow. It was

bitterly cold. I stepped out briskly, glowing inwardly with ambition and hope,

and at last certain of the immediate future – even though I was not on my way

to a Fighter Squadron.

As night drew in and I

approached Houthem, the village stood out in dim silhouette against the dark

wintry sky – the low-built houses, following the main street in its Z-shaped

course past the church, just visible on my right, and, beyond, the windmill,

with its sails outstretched in a broad cross above the mound it stood on, and

the yellow shafts of light escaping through the rifts in the doors and the

shuttered windows. Dark shadows lay on the snow, and my feet sank at every step

and made no sound.

At Houthem I lived in

a cosy little room in the village that I had decorated with brightly-coloured

cretonne. I had naturally tapped the electric current serving our G.H.Q., and my

quarters were exceedingly comfortable. Even so, I was later to grow much fonder

of my little room at Les Moëres, by the side of the aerodrome. An aviator must

live in the shadow of his shed to enjoy life and get the best out of his

calling. The dispersal of the pilots at Houthem was fatal to the corporate

spirit, and as a result the Squadron was divided against itself. The squadrons

at Les Moëres possessed much more esprit de corps.

At Houthem, almost all

the officers of the Squadron – therefore too many – shared a common mess, a

vast, unattractive hall. A small minority lived in the junior mess, also known

as the Potinière, which was established in a wooden building on the other side

of the village.

Belgian General

Headquarters had established themselves at Houthem, wishing in their innocence

to have an aerodrome close by for their defence. They showed less keenness for

this defence when the Germans came across and bombed the aerodrome, and I know

of many pilots who were subsequently able to gain possession of the best rooms

in the village…

At conference time,

Houthem was as animated as an anthill; the High Street was full of cars and

officers greeted one another cheerily. But it did not last long, and as soon as

the meeting was over, the village relapsed into slumber. The flying men were

all in their various messes, and all was quiet save for an occasional outburst

following some high-spirited ‘rag’. The G.H.Q. officers, although more

numerous, were conscious of their position, and therefore made less noise. They

never came near us. They were divided according to their rank, into three

messes, one for the juniors, one for the officers of Field rank, and the third

for General Officers. Their colleagues in the army called these messes the

‘Hospital’, the ‘Asylum’, and the ‘Mortuary’.

In April 1917 Coppens was transferred to the 4me Escadrille,

also based at Houthem and still flying two-seater reconnaissance machines.

While here he was able to fly the Nieuport scout which belonged to Commandant

Hagemans, the commander of the centre at Houthem.

On 15 July 1917 Coppens realised his ambition to become a

fighter pilot when he was posted to 1ère Escadrille based at Les Moëres. They

were commanded by Commandant Fernand Jacquet and operated Nieuport scouts.

Les Moëres Aerodrome

This aerodrome is associated with the formation of the

Belgian Groupe de Chasse and Belgium’s greatest fighter pilot, Willy Coppens.

He claimed all of his thirty-seven victories while based here.

The site of Les Moëres was taken over when the aerodrome at

Furnes became untenable due to shelling by heavy calibre German guns.

Coppens described the aerodrome:

From the point of view

of an aerodrome, the place was far from being ideal as it stood, and a

considerable amount of work was necessary to reclaim the marshy land, on which

the squadron had made its home, before it was really fit for use. This flat

country is criss-crossed by ruler-straight roads, intersecting at right-angles.

These roads are lined with gaunt willow-trees whose grizzled, long-haired heads

frown sullenly across the low-lying landscape, and are separated from the

fields that lie alongside them by dykes that are both wide and deep.

A road, identical with

every other road, leading to two isolated farms in Les Moëres, finished up at

one corner of the aerodrome. Here, away from all traffic, the green canvas

sheds and the various buildings housing the squadron had been erected. The

first wooden hut one reached sheltered the mess, and next to this stood

another, which was partitioned off into ten cubicles occupied by ten pilots,

with a hall in the centre. Additional living accommodation was provided by two

large aeroplane-cases (originally used for the transport of Sopwith

two-seaters), each the size of a railway-carriage, and each subdivided into

three little cubicles opening direct on to the aerodrome. These cases and huts

stood in line, in the shade of a row of willows, alongside a dyke, where the

wind, bringing with it the fragrance of the dunes, used to come and sigh among

the reeds.

The mess had six windows.

In front of each of these was arranged a table to seat four, giving the whole

the appearance of a dining car. Chairs of light oak upholstered in green

velvet, found in an abandoned villa at Coxyde, added to our comfort, and a

piano, at which André De Meulemeester sat for hours at a stretch – for De

Meulemeester was a born pianist of very great skill – lent a note of gaiety

that was greatly appreciated.

The Groupe de Chasse

In March 1918 there was a reorganization of the AMB, when a

dedicated fighter wing was formed. Prior to this, fighter pilots were called

out to escort two-seater machines, or for offensive patrols at the request of a

ground unit or at the individual pilot’s initiative.

Despite the rigid Belgian army policy of promotion by

seniority, King Albert insisted that Fernand Jacquet became the commanding

officer over the heads of more senior officers. His confidence was

well-rewarded as Jacquet welded it into an effective force, although limited in

numbers and still operating a number of types that were obsolescent.

A little of tradition was lost in this reorganisation, as

the 1ère Escadrille became the 9me, the 5me Escadrille was re-numbered the 10me

and a new unit, the 11me, was formed. The Groupe de Chasse established itself

on Les Moëres. Nominally the 9me operated the Hanriot HD1, the 10me the Spad

and the 11me the Camel.

Willy Coppens and the

Hanriot

Born on 6 July 1892 at Watermaal-Bosvoorde, near Brussels,

Willy Omer François Jean Coppens started the war with the 1ère Regiment

Grenadiers. Like a number of Belgian aviators, he learned to fly in the UK and

received his Royal Aeronautical Club certificate, No. 2140, on 9 December 1915.

Following further training at the Belgian Aviation School at Étampes he joined

6me Escadrille in April 1917. Initially he flew Nieuport scouts in the 1ère

Escadrille but shortly a new type of machine arrived. Coppens again:

I was present when the

first Hanriots came, and on this occasion I can assert that the Squadron very

nearly refused them, as I believe it had refused the Spads.

André de Meulemeester

had the first and declined to keep it. He therefore handed it over to

Olieslagers, who declined to keep that which De Meulemeester had no use for.

And so on, and I, being about the last to have joined the squadron, finally had

it offered to me. I fell in love with the Hanriot at first sight. It was light

as a feather on the controls, and the pilot had a wonderfully clear field of

vision.

The Hanriot was

extremely easy to handle and pleasant to fly. It was strong in spite of its

apparent fragility, and was faster and climbed better than the Nieuport.

The HD1 was designed by Emile Eugène Dupont for René

Hanriot’s company in the summer of 1916. Proof tests were carried out on it in

January 1917. Unfortunately, though it was a good design, the excellent Spad

was just coming into large scale production. Also the Hanriot employed the same

engine as the Nieuport scout, which the French were trying to replace, and was

not enough of an improvement over the Nieuport to warrant production for the

French air service. However, it was tested by the Italians who adopted it as

the principal replacement for their Nieuports. A total of 1,700 served with the

Italian air service, of which about half were built in Italy under licence.

The Belgians ordered 125 HD1s, the first being delivered on

22 August 1917. The enthusiasm Coppens displayed for the type eventually

persuaded the doubters, and the 1ère Escadrille was fully equipped with them.

The Hanriot would soldier on into the mid-1920s with both the Italians and

Belgians.

On 22 August 1917 Coppens became the first Belgian to fly a

Hanriot on an operational sortie. During the latter part of the year he made

three claims but they were unconfirmed. On 25 April 1918 he obtained his first

confirmed victory, when he shot down a two-seater, which crashed near

Ramscapelle. The great disadvantage with the Hanriot was that it was only

fitted with one fixed Vickers machine gun. Coppens was able to obtain twenty

rounds of incendiary ammunition and on 8 May he attacked a German observation

balloon and brought it down. This was the first kite balloon shot down by a

Belgian pilot. Just under two hours later he brought another down in flames.

After each of his victories, in his enthusiasm, he gave an impromptu aerobatic

display, much to the enjoyment of the Belgian frontline troops.

From this moment Coppens specialised in attacking

observation balloons. These were difficult and dangerous targets and many

pilots avoided them. On 22 July he shot down three when he had been poaching on

the British part of the front. This was frowned upon by Belgian General

Headquarters but a reprimand was avoided when the British awarded him a

Military Cross for the feat! By the first week in October 1918 Coppens had

claimed 33 balloons and become the most successful ‘balloon buster’ of any

nation.

On the morning of 14 October he took off with Etienne Hage

to destroy a balloon near Vladslo. Coppens again:

I soon caught sight of

the Thourout kite-balloon, ‘flying’ at about 1,800 feet, and at the same time I

saw another at 2,100 feet, over Praet-Bosch. The latter balloon was the higher,

and would therefore require to be attacked after the first – which would have

to be taken by surprise, as quickly as possible, before it was pulled down too

far.

At 6 a.m., I fired

four rounds into the Praet-Bosch balloon now at a height of 2,400 feet, and the

envelope began to burn.

Etienne Hage failed to

see the flames, and instead of following me, went back to the balloon, while

the ground defences fired at us for all they were worth, and the Thourout

balloon, warned, started to go down.

Turning back towards

Thourout, and flying – so far unscathed – through that maelstrom of incendiary

projectiles from the ‘onion’ batteries below, I pondered on my chances of

getting through.

At 6.5 a.m., I sailed

in to open fire on the Thourout balloon, now hauled down to 900 feet, and in

addition to the bursting of the shells, I heard the vicious bark of the

small-calibre machine guns. I was 450 feet away, when I felt a terrible blow on

the left leg.

An incendiary bullet,

after passing through the thin planking of the floor, had struck my shin-bone,

smashing everything in its passage and inflicting a wound all the more painful

for the fact that the bullet, being hollow, had flattened, becoming in effect a

‘dum-dum’ bullet. The muscles were torn apart, the bone shattered, and the

artery cut in half.

Because of the shock and pain Coppen’s right leg went rigid,

pushing the rudder bar, which caused the machine to yaw and enter a spin. At

the same time his hand involuntarily clutched the trigger control, firing his

machine-gun and hosing the bullets in all directions, a few hitting the balloon

and setting it on fire. Fortunately his rudder bar had a foot strap at either

end, so he was able to control it using only his undamaged right foot. He

turned for the safety of the Belgian front line.

A sweat on my forehead

made me snatch down my goggles, so that they remained hanging round my neck,

and pull off my fur-lined cap. I had done all my flying at the front with this

cap, and nothing would have parted me from it; with an effort, I stuffed it under

my coat. On the other hand, I tore off and shed my silk muffler protecting my

face from the cold. I wanted air, ice-cold air, to bathe my face and keep me

from fainting.

Crossing the lines Coppens put his machine down in a small

field by the side of a road, where the weakened undercarriage collapsed. He was

quickly removed from his Hanriot and transferred to the hospital at La Panne,

where he was operated on. For several days he suffered from terrible pain and

fever. King Albert visited him twice and on the second visit insisted that the

doctors amputate Coppens’ leg in order to save his life. While in hospital the

Armistice was signed and he was transferred to hospital in Brussels, until

finally discharged in July 1919.

As befitted his position as Belgium’s most successful

fighter pilot he was heavily decorated, being made an Officier de l’Ordre de

Leopold, an Officier de l’Ordre de la Couronne and received the Croix de Guerre

with twenty-seven palms and thirteen Lion Vermeils, plus twenty-eight citations.

In addition he received the British DSO and the Serbian Order of the White

Eagle. After the war he became a Baron and was persuaded by King Albert to

remain in the army. This was a decision he came to regret, as he spent most of

his years as a military attaché in Italy, France, Switzerland and Great

Britain, receiving little promotion. He left the army in 1940, still only a

major. During the Second World War he lived in Switzerland, organising

resistance work, but in the late 1960s returned to Belgium. For the last five

years of his life he resided with the only daughter of Jan Olieslagers,

Belgium’s fifth most successful fighter pilot of the Great War, until his death

on 21 December 1986.

Furnes/Coxyde

Aerodrome

With the fall of Antwerp, four of the five Belgian

escadrilles moved to Ostend on 4 October 1914. A week later all five evacuated

to St-Pol-sur-Mer but on the 17th I Escadrille moved forward to the aerodrome

at Coxyde (or Furnes as it was known to the British). They were shortly joined

by Escadrilles II and III. Initial equipment consisted of a mixture of Maurice

Farmans and Voisin pushers. Being so close to the front line, the aerodrome was

a target for the batteries of heavy guns established by the Germans along the

North Sea coast.