Napoleon III Takes

Power

That year revolutions ignited by economic distress swept

Europe. Paris, that powder keg of revolutionary passions, erupted in February.

King Louis-Philippe, despised for his cautious and inglorious foreign policy,

abdicated and fled to England. The Second Republic was proclaimed by Paris

radicals, but France became embroiled in internal troubles. Such was the need

felt in the country for a man of order that the presidential election held on

10 December produced a result undreamt of by the revolutionaries of February

when they introduced universal male suffrage: a Bonaparte was restored to power

in France.

Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte was elected President of France by

5.5 million votes: far ahead of his nearest rival. Born in 1808, he was the

nephew of the great Emperor, on whose knee he had been dandled as a child and

whose legend he revered. After Waterloo Louis had lived in exile in Switzerland

with his mother Hortense Beauharnais, and spoke French with a German accent.

During disturbances in Italy in 1831 he had sided with the revolutionaries

against the Austrian regime there. After both his elder brother and his cousin,

‘Napoleon II’, died in 1831–2, Louis assumed the role of Bonapartist pretender

to the French throne. His pamphlets, notably Napoleonic Ideas (1839), promoted

the myth Napoleon had woven around himself in exile on St Helena: of Napoleon

the Liberal, Napoleon the friend of nationalities working for a united Europe,

who had been thwarted by the reactionary monarchies. However, his first

attempts to exploit his uncle’s legend against King Louis-Philippe ended in

farce. An attempted military rising at Strasbourg in 1836 was a debacle and

earned him a sentence of exile. A second attempt, a landing at Boulogne in 1840

with a boatload of volunteers and mercenaries who had joined him in London, was

quickly overpowered by royal troops. This time Louis was imprisoned in the damp

northern fortress of Ham. He escaped disguised as a workman in 1846 and fled to

London where, supplied with money by his rich friends and English mistress, he

was well placed to take advantage of events unfolding in 1848.

In the presidential campaign his supporters adeptly promoted

the power of the Bonaparte name, using images that appealed to classes who had

never before had the vote. Not for the last time, bourgeois professional

politicians underestimated the powers of this unimpressive figure, whose

tendency to stoutness, drooping eyelids, and hesitant, heavily accented

delivery belied his political skills and determination. As Prince-President, he

swore to defend the Republic and toured the country, promoting himself as the

only man who could defend both liberty and order and reconcile internal

divisions that lately had made France seem ungovernable. Continuing radical

disturbances rallied conservatives to him as a man of order. Catholics approved

of a new education law favouring religious schools, and of the despatch of an

expeditionary force to protect the Pope from revolutionaries at Rome.

Louis-Napoleon’s championship of universal male suffrage against the bourgeois

politicians of the National Assembly who tried to restrict it made him appear a

defender of democracy.

His appeal to many groups, combined with shrewd appointments

of supporters to key posts, put him in a strong position to extend his

presidency, which was due to end in 1852. The National Assembly, however,

blocked his attempt to achieve this legally. Louis, with careful planning by

his inner circle and the support of reliable generals and his police chief,

staged a coup d’état on the night of 2 December 1851, the anniversary of his

uncle’s victory at Austerlitz. The Assembly was locked out; its leading

politicians were arrested and imprisoned.

‘Operation Rubicon’ did not go as smoothly as planned,

however. On 3 December a Deputy of the National Assembly, Dr Baudin, was killed

on a Paris barricade. Next day over a thousand protestors manned barricades in

the city. Troops opened fire and killed dozens of them and bystanders too. In

the provinces over 26,000 people were arrested, half of whom were deported,

banished or imprisoned. Throughout the nineteen years of his rule, the ‘crime

of 2 December’ blighted Louis-Napoleon’s attempts to win over a hard core of

opponents to accept the legitimacy of his regime. Nevertheless, the great

majority of French voters supported him when he sought popular endorsement of

his coup. He had brought something new to European politics; a dictatorship

resting on popular approval, but supported by strict censorship, police

surveillance and electoral manipulation. Pressing his advantage, in November

1852 he sought approval for restoration of the Empire and got it by 8 million

votes to 250,000, with 2 million abstentions. With effect from 2 December 1852

he declared himself Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, and shortly

promulgated a constitution that preserved the forms but not the substance of

parliamentary government.

To calm fears at home and abroad that the return of the

Empire meant war, he declared at Bordeaux in October 1852 that ‘The Empire

means peace’, and that his focus would be on internal improvements like

building roads, railways, dockyards and canals. He was careful to cultivate his

uncle’s old nemesis, Great Britain. Despite his peaceful professions, he

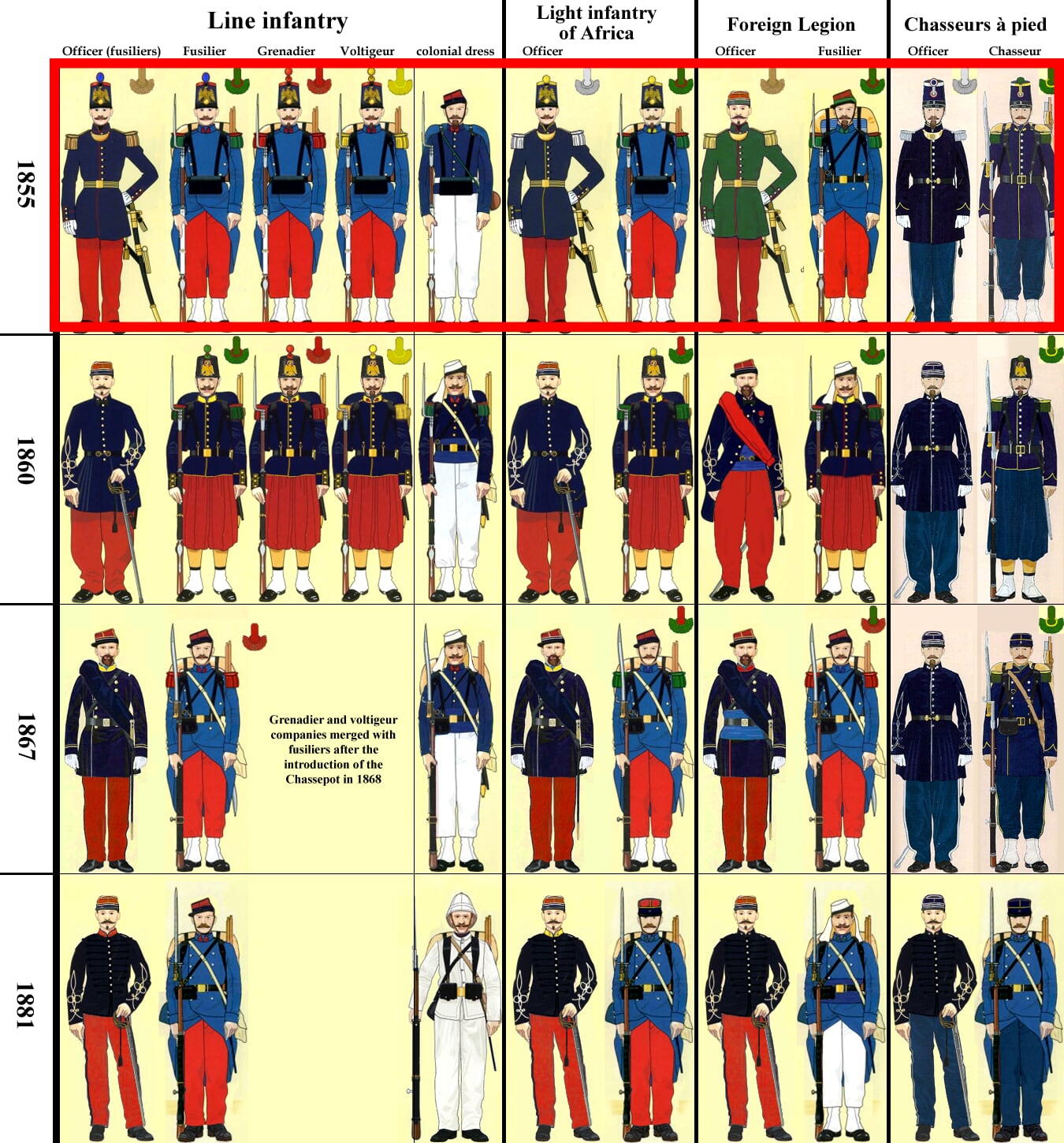

cultivated the army, recreated an elite Imperial Guard, and frequently appeared

in military uniform, in deliberate contrast to the black-coated dullness of

Louis-Philippe’s court. Like all French governments since Waterloo, he nurtured

hopes of burying the 1815 treaties. Unlike the Bourbon monarchs, but like the

republicans of 1848, he sympathized with the cause of nationalities in Europe.

He might be expected to act in their favour where opportunities arose.

A Franco-German

Crisis, 1859

A shift in Great Power relations came sooner than anyone

foresaw, as a result of the Crimean War of 1854–6, in which Britain and France

combined to defeat Russia’s attack on the ailing Turkish Empire. The defeat her

army suffered at allied hands at the long siege of Sebastopol exposed Russia’s

weaknesses and discouraged her from active intervention in European politics

for two decades while she undertook internal and military reforms.

The war had another important consequence for European and

German politics: it isolated Austria. Like Prussia, Austria had wished to stay

neutral, but Russian forces at the mouth of the Danube intruded on her vital

interests. Her long resistance to joining the western camp won her no friends;

yet her eventual signature of an ultimatum to Russia weighed heavily in

Russia’s decision to accept peace terms. Russia regarded Austria’s action as

rank ingratitude for the military help she had received in 1849, and an

intolerable betrayal by a fellow conservative power. In future Austria could

expect no Russian help if she needed it; indeed, Russian court circles desired

to see her punished. Prussia, which had not intervened against Russia and had a

common interest in keeping the Poles suppressed, was on the contrary seen as

Russia’s only friend in Europe.

If Russia and Austria were losers, victorious France gained

prestige. Napoleon III’s army had acquitted itself well, albeit at the cost of

95,615 French lives. It had made up the majority of allied land forces and had

shown itself less incompetent than any other in the field; even if the latest

communications technology, the electric telegraph, had proved a mixed blessing.

One French commander-in-chief in the Crimea, Canrobert, had resigned in despair

over orders wired direct from the Emperor in Paris. The 1856 peace conference

was held in Paris, where Napoleon invited the delegates to banquet and waltz at

the Tuileries Palace and savoured his moment as arbiter of Europe. His chances

of founding a stable dynasty improved when the Empress Eugénie gave birth to a

healthy male son, Louis, the Prince Imperial.

In 1858 Napoleon exploited his diplomatic and military

advantages in the hope of ‘doing something for Italy’. Having long desired to

help the Liberal and national cause there, he secretly agreed with the Kingdom

of Piedmont to drive the Austrians out of the parts of Italy they had occupied

since 1815. Napoleon was mixing idealism with opportunism, for he had the

chance to achieve military success, weaken reactionary Austria while she was

isolated, create client states in northern Italy, and regain Nice and Savoy as

the price of his support. Yet, as conflict became imminent, his resolve

faltered, even once he was sure of Russia’s neutrality. Napoleon was finally

pulled over the brink only when, provoked by Piedmontese military preparations,

Austria obligingly declared war in April 1859.

The Italian campaign showed how much warfare had changed

since Waterloo. The French army was transported by railway and steamship,

debouching over the Alps and to the port of Genoa in three weeks. At close hand

there was much that was chaotic about French supply arrangements: Napoleon

lamented privately to his War Minister that ‘What grieves me about the

organization of the army is that we seem always to be … like children who have

never made war … Please understand that I am not reproaching you personally;

rather the general system whereby in France we are never ready for war.’ Yet to

outside observers it seemed that the French army was again proving itself the

best in the world. With no interference from the sluggish Austrians it

completed its concentration, outmanoeuvred the enemy and marched across the

north Italian plain, winning bloody battles at Magenta and Solferino in June.

If little tactical brilliance was on display, French troops showed the superior

élan and willingness to get to close quarters that made them so formidable.

Their senior commanders, driven by the instinct that getting close to the enemy

was the path to honours and promotion, included men who would command armies in

1870. The courtly aristocrat Maurice MacMahon, already distinguished for his

successful assault on the formidable defences of Sebastopol in the Crimea, won

his marshal’s baton and the title of Duke for his performance as a corps

commander at Magenta.

Decorations, promotions, and victory parades in Milan and

Paris were one side of French success in Italy, but another shocked European

opinion. Solferino, a savage battle involving 300,000 men, produced 36,000

casualties by the time a thunderstorm of extraordinary violence put an end to

fighting. With none of his uncle’s ruthless indifference to high casualties,

Napoleon III was sickened by what he saw and smelled on the battlefield next

day. In a famous pamphlet, the Swiss traveller Henry Dunant described the

horrors of the battlefield. The army medical services were overwhelmed.

Dunant’s lurid description rallied widespread support for the initiative of a

group of Swiss philanthropists, who in 1863 founded the International Society

for Aid to the Wounded, later known as the International Red Cross. The

Society’s efforts gave birth to the Geneva Convention of 1864, which laid down

an international code for the humane treatment of wounded enemies and prisoners

of war, and conferred neutral status on medical personnel. Prussia was among

the first and most enthusiastic states to sign the Convention. France signed

too at the Emperor’s behest, despite the reservations of military men who had

no wish to see hordes of civilian volunteers working in the battle zone.

This was for the future. In the wake of Solferino Napoleon

decided to end the war. He and Emperor Franz Josef of Austria met and agreed

peace terms at Villafranca on 11 July. It was not simply that Napoleon had

little stomach for further battles. Typhus was spreading in his badly fed army,

camped under the torrid Italian sun. He had conquered Lombardy for Piedmont,

but if he wanted to force the Austrians out of Venetia he faced a long and

difficult war for which there would be diminishing support in France.

Revolutionary support for Italian unification in central Italy was getting out

of hand, threatening the Papal territories around Rome and alarming French

Catholics. Worryingly, too, Prussia was mobilizing her army.

In the German states, Napoleon’s war in Italy was execrated

as naked aggression against Austria. Fear that Napoleon’s next goal would be

the Rhine revived enthusiasm for and debate about German unity as nothing else

could. Newspaper and pamphlet denunciation of French ambitions was as virulent

as in the crisis of 1840, and much slower to subside. Yet popular sentiment did

not produce cooperation between Prussia and Austria. As she had in the Crimean

War, Prussia obstructed proposals for the German Confederation to mobilize

forces to support Austria. Finally, in mid-June, Prussia mobilized six of her

nine army corps, but as the price of her support sought command of

Confederation forces on the Rhine front. The suggestion made sense while

Austria was under attack in Italy, but her mistrust of Prussian ambitions in

Germany was such that she refused to yield precedence on this point. For the

Austrians too, Prussian mobilization provided an incentive to make peace

rapidly.

Even without an ultimatum, Prussia’s show of strength was

sufficient to cause Napoleon alarm for his eastern frontier. He feared that the

Prussians could put 400,000 men on the Rhine in a fortnight. This expectation

was slightly exaggerated. Helmuth von Moltke, the studious and methodical

Prussian Chief of General Staff, worried that in the present state of the

German railway network – much of which was still single-tracked – it would take

at least six weeks to move a quarter of a million men to the frontier. At all

events, Napoleon concluded that he was in no position to fight the Prussians

while continuing his campaign against Austria. Peace was concluded. The

Prussians demobilized from 25 July, and the French eventually withdrew all

their forces from Italy save for a garrison to protect the Papal territory of

Rome, which Catholic opinion at home demanded. As his price for accepting the

transfer of the central Italian states to Piedmont, Napoleon received Nice and

Savoy following plebiscites in all the affected areas. The recovery of these

two territories on France’s south-eastern border was his first reversal of a

loss France had suffered in 1815: a gain which boosted the popularity of his

regime at home. The other powers, and particularly the German states, were

greatly alarmed that it might not be his last. After his Italian adventure it

was hardly surprising that Napoleon III was feared as the ruler most likely to

disturb the peace of Europe.