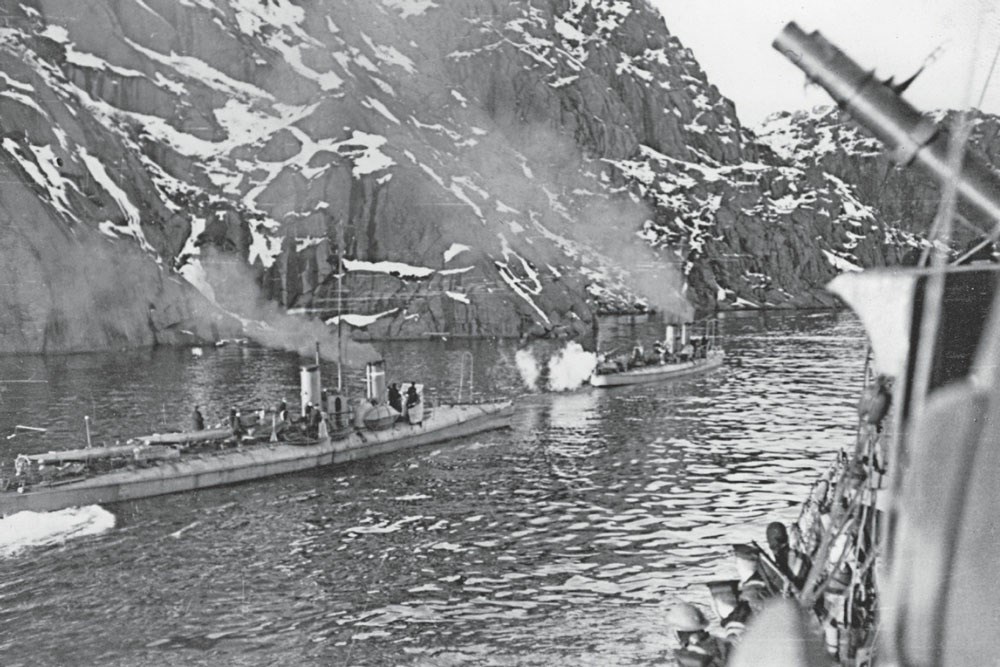

The Norwegian torpedo boats Kjell and Skarv positioning themselves between

Altmark inside the fjord and Ivanhoe just outside.

At midday, a signal from the Admiralty reported Altmark in

Swedish waters, at the head of the Kattegat. This caused some confusion until

it was discovered that the decoding of the signal was erroneous and the name

initially read as `Veaden Rev’, should probably be `Jaederens Rev’, an

old-fashioned spelling of Jærens Rev, the shallows south of Stavanger. During

the next couple of hours, a number of sighting reports were received, with

positions differing by up to 25 miles. One problem was that nobody knew what

Altmark looked like. The only photo available was one from the Illustrated

London News, but there were two ships in the photo and the caption did not

indicate which was the German tanker. Eventually, Vian decided to split his

force. Arethusa with Intrepid and Ivanhoe should cover the area off Egersund

while Cossack, Nubian and Sikh would make a sweep south towards Lista. Tension

was running high, and fire was opened on what was thought to be a German

reconnaissance aircraft but turned out to be a Hudson from Coastal Command,

sending off the wrong recognition signals.

In the early afternoon of the 16th, Altmark and Fireren were

just off Obrestad Lighthouse south of Stavanger when they were sighted by a

battle flight of three Hudsons. The aircraft from 220 Squadron at Thornaby were

flying northward in a loose line-abreast approaching Stavanger, when two ships

were observed: one of them a small auxiliary, the other a large tanker. The

aircraft passed inside Norwegian territory, circling the larger ship for a

proper identification. The name Altmark was painted in white on both sides aft,

below the swastika flag, and there was no doubt that they had found the tanker.

Altmark’s position was reported to the Admiralty at 12:55 and forwarded to

Arethusa and Cossack at 13:18. Fireren had no A/A guns and Kaptein Sigurd Lura

could only hoist a protest signal against the intruding aircraft. Cossack and

her group were far south of the reported position, but Arethusa, Intrepid and

Ivanhoe were close and turned to investigate. At 13:50 (BrT), Gunnery Officer

Lieutenant Roberts reported from Arethusa’s director control tower that he

could make out a vessel close to the Norwegian coast and believed her to be

Altmark.

Around 16:00 Norwegian time, the torpedo boat Skarv

commanded by Loytnant Herman Hansen replaced Fireren as escort to Altmark as

she passed Egersund. Shortly after, three ships came into view from the

south-west. They closed at speed and could soon be identified as a British

cruiser and two destroyers. Paralleling the tanker’s course, just outside the

Norwegian territorial limit, Arethusa flashed a signal, ordering Altmark to

`steer west’, out of Norwegian territory. Dau ignored the order and continued

hugging the coast. He could not believe that the British would violate

Norwegian territory in broad daylight in front of a RNN torpedo boat. Captain

Graham of Arethusa believed his orders from the Admiralty were clear enough,

though. He sent a signal to Vian, confirming he had located the German ship,

and ordered Intrepid and Ivanhoe to intercept and board her while he covered

from outside the territorial limit. The two destroyers turned inside Norwegian

territorial water at speed, Ivanhoe hoisting the flag signal `Steer west’, Intrepid

flashing `Heave to, or we fire’. There was no reaction.

At 16:30, Lieutenant Hansen sent a wireless signal from

Skarv to his superiors in Kristiansand with information that British naval

ships had been sighted. Ten minutes later a supplementary signal said they were

now inside Norwegian waters, apparently intending to intercept Altmark. Hansen

steered his nimble torpedo boat towards Intrepid, the nearest of the

destroyers. Through bold manoeuvring, he managed to keep Skarv between Intrepid

and Altmark, protesting at their presence inside Norwegian waters by

loudhailer. Commander Roderick Gordon hailed back that Altmark was also in

Norwegian waters – with prisoners on board. Hansen answered that the German

ship had been searched, and no prisoners found. In frustration, Gordon turned

180 degrees and, as expected, the torpedo boat followed. After two miles he

turned Intrepid back towards Altmark again, increasing to 25 knots, leaving

Skarv behind.

When well away from the Norwegian, Gordon gave the order to

fire a warning shot on the tanker. The 4.7-inch shell ricocheted off the water

some 220 yards behind the tanker and landed harmlessly inland at Stien near

Rekefjord. Two more rounds were fired, and Dau finally lost his nerve. Altmark

started to slow down. Intrepid slowed too, and lowered her whaler with a

boarding party on board. Seeing this, Dau ordered speed again, and the whaler

could not catch her. Skarv had in the meantime caught up with Intrepid and

Lieutenant Hansen again hailed a protest against the violation of Norwegian

territory. Commander Gordon answered that he was under orders to intercept

Altmark and bring her to England. Hansen repeated his protest, to which Gordon

replied: `I have my orders.’

While Skarv was busy with Intrepid, Commander Philip Hadow

took Ivanhoe close to the tanker in an attempt to force her out to sea. Advised

by the two Norwegian pilots, though, Dau steered Altmark inside a small cluster

of islands named Fogsteinane, where there was little room to manoeuvre. Hadow

decided it was time to board and tried to manoeuvre close enough to Altmark’s

starboard side to allow his boarding party, which was standing by, to jump

across. Michael Scott, one of the officers of Ivanhoe, later wrote:

Standing where I was

on the bridge, the Altmark presented an unforgettable sight. A ship of some

10,000 tons would, I think, cause comment when not a single soul was to be seen

on deck, but in wartime, and especially when a ship is about to be boarded, it

seemed to me to be so sinister and unrealistic that I thought there must be

some strategy in it, particularly as we had heard that she carried guns. But

nothing happened and she proceeded towards the fjord entrance. [.] We increased

speed and came up quite fast on her starboard quarter.

Just as Ivanhoe’s bow started to close on Altmark’s

quarterdeck, Dau increased speed to about 10 knots and Altmark slipped to port,

all the time closing the mouth of Jossingfjord, opening up behind Fogsteinane.

The destroyer was sheared off by the tanker’s propeller wash, and the chance to

board was lost. Orders had been given from Arethusa to machine-gun the bridge

of Altmark if she refused to stop. Two of the men seen on the bridge were

identified as Norwegian pilots, though, and Hadow decided not to open fire.

Entering the scene off Jossingfjord at this stage was the

torpedo boat Kjell, under the command of Loytnant Finn Halvorsen. Both Kjell

and Skarv were pre-WWI design and, though their torpedoes still demanded

respect from the British destroyers, they had no more than two 47-mm and one

76- mm guns between them. Being senior, Halvorsen took command and radioed

Hansen for a situation report. Getting this, he hoisted the `protest’ flag and

positioned his boat in the way of Ivanhoe, which had to veer off the pursuit of

Altmark. The two warships were at hailing distance and Lieutenant Halvorsen

shouted a protest at the intrusion of Norwegian territory across the sea.

Surprisingly, Hadow shouted back in German and Halvorsen interrupted him with a

`Please speak English, sir’ that caused some amusement on the bridge of the

destroyer. Halvorsen’s repeated protests made the two British destroyers slow

down, and Altmark slipped inside Jossingfjord, the narrow entrance to which

appeared between two small lighthouses.

In Jossingfjord, the sixteen-year-old Wilhelm Dydland was

looking after his boat, which had been landed for the winter. Sometime around

17:00, he heard loud noises from the sea and shortly afterwards a huge vessel

came into the fjord at speed. Surprised, he ran out onto the barren sea-cliffs

to look. As it passed close by him, a man came out on the bridge wing of the

tanker and shouted in Norwegian, asking if the fjord was deep enough to enter.

The baffled youngster waved and shouted back that it was all right and watched

Altmark sweep by into the fjord, making loud noises as she opened a wide swathe

in the 2-3-inch-thick ice covering the fjord some hundred yards inside the

entrance.

At 17:10, as he entered Jossingfjord, Dau sent a telegram

via the nearest coast radio station to the German Embassy in Oslo, advising

that he was `under land’ and that a British destroyer was attempting to come

alongside. Arethusa attempted to jam her transmissions at first but then

stopped, as it was believed it would be better to intercept the message and

perhaps learn the German’s intentions. At 17:55, a second signal was sent from

Altmark to the embassy, informing that she was safely inside Jossingfjord,

protected by two Norwegian torpedo boats, but with Intrepid hovering outside.

Later, a third signal requested the embassy to `make strong protest against the

conduct of the English naval forces’. The German B-Dienst followed the events

closely and, besides intercepting most of the British signal traffic, also

picked up Dau’s signals to Oslo, forwarding them to the SKL and Group West.

In Berlin, the SKL assessed the situation continuously but,

unlike Dau, they had no expectations that the British would respect Norwegian

territorial waters. In a signal at 18:12, Altmark was ordered to seek shelter

in `Lister Fjord or the nearest torpedo safe anchorage’. Remembering the

Norwegian reactions to City of Flint dropping her anchor, though, a modified

signal followed only minutes later: `Do not anchor, but spend the night in a

secure area’. The SKL also considered sending a destroyer force covered by the

cruiser Hipper and at least one battleship towards Norway, but because of the

ice conditions the readiness of the ships was low and they would not be able to

take to sea until the next morning, at best. Instead, instructions were sent to

Naval Attaché Schreiber in Oslo to contact the Norwegian authorities and make

sure they would do their utmost to ensure Altmark was safe.

Schreiber contacted the Admiral Staff around 18:45 and was

informed that the RNN was aware of the situation and that every step necessary

would be taken. Having eventually received the second and third of Dau’s

signals (the first was received at Farsund radio in spite of Arethusa’s jamming

but never delivered to the embassy), Schreiber telephoned the Admiral Staff

again at around 21:50, while Minister Bräuer called Under-Secretary Jens Bull

in the Foreign Office, requesting information. Both were told that information

was scant at the moment, but the RNN had the situation under control and

Altmark was safe. Should anything happen during the night, the embassy would be

informed.

The British naval attaché, Rear Admiral Boyes, on the other

hand, was invited over to the Admiral Staff during the evening. Here, the head

of Naval Intelligence, Kaptein Erik Steen, showed him Jossingfjord on a map and

explained the situation as he knew it. It was emphasised that Altmark could not

escape without eventually leaving Norwegian territory – at which time British

ships could intercept her without infringing Norwegian neutrality. If Captain

Dau chose to stay in Jossingfjord, Norwegian authorities would eventually be

compelled to `take care of the prisoners’. Either way, Boyes was asked to

confirm that British naval ships would not enter Norwegian waters again,

attacking Altmark, as the situation was under control. It has not been possible

to ascertain if Admiral Boyes actually forwarded this information.

Few islands shelter the desolate part of the Norwegian coast

known as Dalane from the North Sea. In 1940, the population of the region was

very small and, apart from the village of Hauge and its harbour Sogndalstrand,

only a few farms and settlements lay scattered among the mountains. From the

sea, the area looks uninviting and that February the heavy snow cover went

almost down to the sea, adding to the desolation. Jossingfjord is one of the

few places large enough to shelter a ship the size of Altmark. Next to the

small fishing settlement of Jossinghavn, there was also a simple deepwater quay

with ore-loading facilities near the head of the fjord. The export of titanium

ore had been halted by the war and the facilities were not in use at this time.

With Altmark entering Jossingfjord shortly after 17:00, the

situation settled for a while. Lieutenant Halvorsen let Kjell follow Altmark

through the opening she made in the ice while Skarv laid-by just inside the

mouth of the fjord, blocking the entrance. Ivanhoe remained just outside, well

inside Norwegian territory, while Intrepid pulled back, retrieving her whaler

with the unsuccessful boarding party. Lieutenant Halvorsen wanted to talk to

the master of Altmark. The ice prevented Kjell from coming alongside the

tanker, though, and the two captains had to use their loudhailers over the

stern of the tanker. Dau told Halvorsen there were around 130 men on board his

ship, which had already been inspected by the Norwegian Navy several times,

including by `the admiral in Bergen’. He, Dau held, had given them `right of

passage’. This was confirmed by the pilots, with whom Halvorsen also spoke.

Content for the time being, Halvorsen took Kjell out of the fjord to hear what

the British had to say. Meanwhile, Captain Vian had arrived and Cossack was

alongside Ivanhoe to receive a report from Commander Hadow. Sikh and Nubian

remained offshore with Intrepid and Arethusa guarding against U-boats.

Having been updated, Vian instructed Paymaster

Sub-Lieutenant Geoffrey Craven, who spoke German as well as basic Swedish, to

invite the captain of the Norwegian torpedo boat to come on board Cossack to

try to sort out the mess. Halvorsen accepted and came aboard the destroyer. The

twenty-nine-year-old lieutenant, who spoke good English, protested firmly over

the violation of Norwegian neutrality and presented his senior British

colleague with an English version of the neutrality regulations. Vian answered

that there were `400 starving British prisoners’ on board Altmark, demanding

the right to board the German tanker and search for them. Undaunted, Loytnant

Halvorsen answered that Altmark had been inspected by the RNN and that he had

not been informed of any prisoners. Vian suggested British and Norwegian

officers should jointly inspect Altmark and settle the issue of prisoners once

and for all. Halvorsen replied he could not authorise this as the German ship

had permission to transit Norwegian waters. He repeated the seriousness of the

situation and urged Vian to leave Norwegian territory immediately. The

discussion was held `in a firm but polite manner’, according to Halvorsen in

his report to SDD1. Others describe it as somewhat heated at times, the

Norwegian lieutenant at one stage threatening to use torpedoes if the British

ships did not leave within thirty minutes. Eventually, Vian must have felt it

imprudent to board Altmark as the situation had developed, and he stood down.

Around 18:30, after Halvorsen had left Cossack with promises to have Altmark

searched again, he ordered Ivanhoe to follow him outside the territorial limit.

Two `Most Immediate’ signals were dispatched from Cossack to

the Admiralty and repeated to Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleet. The first at

17:32 (16:32 BrT):

Fiord is dead end.

Expect no change from Norwegian gunboat, who is examining Altmark. A second

gunboat has a torpedo tube trained on me. Altmark is apparently being

effectively jammed by Arethusa. She is painted warship grey.

The second at 18:57 (17:57 BrT):

Commanding Officer of

Norwegian gunboat Kjell informs me that Norwegian pilots on board Altmark

report that vessel was examined in Bergen yesterday, 15th February, and

authorised to travel south through territorial waters. He said that vessel was

unarmed and nothing was known of British prisoners. I have withdrawn outside

territorial waters and awaiting your instructions. Have stopped Arethusa

jamming.

Dau was in an awkward position, but considered his ship safe

as long as he remained inside Jossingfjord. With the Norwegian torpedo boats between

him and the British destroyers the matter had become a political issue, which

from now on could be left for Berlin to handle. He had certainly no intention

of creating any pretext for British or Norwegian interventions and was content

to stay where he was for the moment. Altmark was moved as far into the fjord as

possible and halted against the ice near the eastern side as darkness started

to fall. Anchors were not dropped and the engines were kept running to be able

to move at short notice. The two Norwegian pilots went ashore but, of all

things, two local customs officers came on board. At the time, nobody seems to

have realised that by going into the fjord, Altmark had was no longer in an

`innocent passage’ of a neutral fairway, but had entered inland waters and

hence, changed her legal definition according to the Hague Convention.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Halvorsen sent Kjell to join Skarv

blocking the entrance to the lane through the ice that the tanker had made,

while he himself went ashore in Jossinghavn. The radios of the Norwegian ships

were useless between the high mountains surrounding the fjord and Halvorsen

used the only telephone in the settlement, dictating a detailed report to his

superiors in Kristiansand. Concluding his report, Halvorsen asked for

permission to search Altmark again to ascertain whether she had prisoners on

board or not. Fireren, which had been ordered from Egersund to Jossingfjord,

arrived at around 20:40. Kaptein Lura was senior Norwegian officer on site, but

left the contact with Cossack to Halvorsen. To maintain communication with

Kristiansand, a man was left at the telephone in the house some 30-40 yards

away from the Holmekaien pier where Fireren moored. He was in shouting contact

with the auxiliary, who used a signal lamp to the torpedo boats that lingered

further out. Through this primitive but efficient system, naval and political

authorities were kept informed as the situation developed and could give their

orders and instructions without much delay.

During the evening a reply to Lieutenant Halvorsen’s request

arrived directly from Rear Admiral Smith-Johannsen of SDD1; Altmark was not to

be inspected again. If, during the night, the British forces made moves to

board the German tanker, the torpedo boats should prevent this – if necessary

by force. It was believed that moving their boats between Altmark and any

British destroyer would be adequate, as boarding the tanker across a Norwegian

deck would be out of the question. Shortly afterwards the order to use force was

recalled by the commanding admiral, allegedly after orders from the Foreign

Office. Loytnant Halvorsen had been denied all possibility of resisting the

intruders in spite of his successful efforts earlier in the day.

On the night of 15/16 February, the British mine-laying

submarine Seal had laid a 3-mile long net off the Fogsteinane islands not far

from Jossingfjord. The hope was that Altmark would entangle herself in the net

and stop or, seeing the net, would venture outside Norwegian territorial waters

to be intercepted. Instead, it was the 5,805-ton German ore ship Baldur on her

way south from Kirkenes that became entangled in the net and started to drift

helplessly westward. An aircraft from Coastal Command sighted her, thought she

might be Altmark, and reported the sighting back to base. Intrepid and Ivanhoe

were ordered to investigate. Michael Scott of Ivanhoe wrote:

It must have been at

about 21:30 [BrT] that the First Lieutenant, who was on watch at the time, saw

a darkened ship going in a southerly direction. We closed on her, put the

searchlights on to her bridge and found once again that it was another ship

flying the German flag. She was signalled `Stop Immediately’ and a warning shot

was fired across her bows. [.] The only reply we got to that was `What do you

want?’ flashed to us in English. We then fired another shot and she stopped

immediately. Things then happened very swiftly. The upper part of the bridge of

the Baldur suddenly began to pour forth clouds of smoke which burst into

flames. The ship began to settle and we waited to pick up the survivors. Two

lifeboats were seen being lowered, one of which made for the Intrepid and the

other for the shore with us in pursuit!

The German ship was quickly engulfed in flames and, fearing

an explosion, Commander Hadow recalled the whaler with a boarding party just

launched from Ivanhoe, picking up the men from the lifeboat instead. Captain

Vian later wrote in his report that as `the sea was calm and the night moonlit,

the two destroyers should have attempted to go alongside and board the

freighter straight away to prevent scuttling.’ Baldur sank during the night.

Having withdrawn outside Norwegian territory and sending his

reports, Vian settled down to wait. The ice conditions observed in the Skagerrak

meant that Altmark for the moment could not reach Germany without eventually

leaving Norwegian territory. German ships and aircraft could be expected at

daylight, but Vian’s force was strong and three submarines, Triad, Seal and

Orzel, were also in the area. The longer Altmark stayed in Jossingfjord, the

more likely it was that the Norwegian government could be swayed to accept a

thorough inspection of the vessel including British officers, or at least

British officials.

In London, Churchill had arrived in the Admiralty War Room

with DCNS Rear Admiral Phillips, alerted by the news of Altmark being found. He

was in no mood for patience or diplomacy and, with Admiral Pound not present,

Churchill took matters into his own hands. Having conferred with Foreign

Minister Halifax, but without going through Admiral Forbes, who was Vian’s

superior, Churchill submitted explicit orders to Cossack at 17:50 (BrT):

Unless Norwegian

torpedoboat undertakes to convoy Altmark to Bergen with a joint Anglo-Norwegian

guard on board and a joint escort, you should board Altmark, liberate the

prisoners and take possession of the ship pending further instructions. If

Norwegian torpedoboat interferes, you should warn her to stand off. If she

fires upon you, you should not reply unless attack is serious, in which case

you should defend yourself using no more force than is necessary and cease fire

when she desists. Suggest to Norwegian destroyer that honour is served by

submitting to superior force.

Captain Vian must have realised that the signal bore

Churchill’s mark and that his next few actions would at best be critical for

his career. The signal crossed his own request for instructions and was shortly

after supplemented by a brief: `Your 1757/16 received. Prisoners probably hidden

onboard. Carry out my 1750/16.’

Vian signalled `I go alone’ to the other ships and ordered

Lieutenant Commander Bradwell Turner, Cossack’s first officer, to prepare the

boarding party. This consisted of forty-five sailors, largely from the cruiser

Aurora, embarked for the occasion as Cossack had a number of her crew down with

a bout of flu. The men were grouped in four sections; each allocated a part of

the German ship to take control of.

It was a cold but clear night as the moon was up, giving a

fair visibility. At around 22:45, Vian took Cossack back into Norwegian waters

east of Fogsteinane. The waters are foul here and the RNN officers wondered at

the recklessness of the British captain. On the bridge of Cossack, however, the

pilot officer, Lieutenant Commander MacLean, had to admit to Vian that he had

followed the wrong lights ashore and asked if he could have the searchlights

switched on to see where he was. This was done and she made it safely through

the straits, but comments on the bridge were that history would show Cossack

coming in with lights blazing – when in fact she was lost. At 23:12 (22:12

BrT), as Cossack entered Jossingfjord, a third signal from the Admiralty

arrived:

If offer of joint

escort and guard to Bergen is not accepted and you have been forced to board,

action is to be taken as follows: If no prisoners are found to be onboard, ship

is to be brought in as a prize. If no prisoners are found and ship is

definitely Altmark, Captain and officers are to be brought to England in order

that we may ascertain what has been done with prisoners. Ship to be left in

fjord.

In general, there is a notable inconsistency among the

accounts of the participants in the subsequent events at Jossingfjord this

evening. British, Norwegian and German reports differ widely; more so the

longer after the events they have been written. Most parties appear to have had

a growing need to justify their actions – or lack thereof. The following is an

attempt to piece it together as accurately and objectively as possible from the

original sources.