October 732

Forces Engaged

Franks: Unknown. Commander: Charles Martel.

Moslems: Approximately 20,000-80,000. Commander: Abd

er-Rahman.

Importance

Moslem defeat ended the Moslem’s threat to western Europe,

and Frankish victory established the Franks as the dominant population in

western Europe, establishing the dynasty that led to Charlemagne.

Historical Setting

During 717–718, Moslem forces tried and failed to capture

Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire. That was a major setback for

the Moslems, whose forces (intent on spreading their faith) had been virtually

unstoppable in conquests that spread Islam from India to Spain. Although that

defeat kept the followers of Mohammed out of eastern Europe for another seven

centuries, it must have motivated other Moslems to attempt to spread the faith

into Europe via another route: North Africa into Spain into western Europe.

Moslem forces had spread across the southern Mediterranean

coast through the later decades of the seventh century and in the process of

converting their conquered enemies absorbed them into the armies of the

faithful. In North Africa, some of the most ardent converts were Moors (called

Numidians by the Carthaginians of Hannibal’s time), the Berbers of modern

Morocco. In 710, Musa ibn Nusair, Moslem governor of the region, decided to

attack across the Straits of Gibraltar and raid Spain. Without ships, however,

he turned to Julian, a Byzantine official, who loaned him four ships. Julian

did this because of a grudge he bore against Roderic, the Visigoth king that

ruled in Spain. With four ships able to carry 400 men, Musa launched a raid

that netted him sufficient plunder to whet his appetite for more.

In 711, he ferried 7,000 men across the straits under Tarik

ibn Ziyad. Although this was originally intended to be simply a larger raid,

Tarik’s victory over Roderic opened the Iberian peninsula to Moslem troops.

Within a year, Musa was back in command and master of Spain. Recalled to the

Middle East by the caliph, Musa’s successor, Hurr, pushed deeper into Spain and

through the Pyrenees into the province of Acquitaine during 717–718. Over the

next several years, Moslem power ebbed and flowed through southern, central,

and even northern Gaul (France).

The arrival of the Moslems was fortuitously timed, as

internal feuds divided the population of Gaul. The dominant population, the

Franks, were in a slump. Upon the death of Pepin II in 714, the Frankish throne

was disputed between Pepin’s legitimate grandson and illegitimate son. Eudo of

Acquitaine saw an opportunity to escape Frankish domination, so he declared his

independence and received in return the wrath of Charles Martel, Pepin’s

illegitimate son who finally succeeded to the throne in 719. After defeating

Eudo, Charles then turned toward the Rhine River to secure his northeastern

flank. He made war against the Saxons, Germans, and Swabians until 725, when

Moslem successes in southern Gaul diverted his attention.

While Charles was off fighting in Germany, Eudo feared for

his future because he was located between aggressive Moslems to the south and a

hostile Charles to the north and east. Eudo entered into an alliance with a

renegade Moslem named Othman ben abi Neza, who controlled an area of the northern

Pyrenees. That alliance provoked Abd er-Rahman, Moslem governor of Spain, who

marched against Othman in 731. After defeating him, Abd er-Rahman decided to

drive deeper into Gaul, spreading Moslem influence and, more importantly,

looting the wealthy Gallic countryside. He defeated Eudo at Bordeaux and

proceeded north toward Tours, whose abbey was reputed to hold immense wealth.

To spread as much terror and accumulate as much loot as possible, Abd er-Rahman

divided his army, probably some 80,000 strong, into several columns and sent

them pillaging.

Eudo fled to Paris, where he met with Charles and begged his

aid. Charles agreed on the condition that Eudo would swear loyalty and never again

try to remove himself from Frankish dominion. With that promise, Charles

gathered together as many men as he could and marched toward Tours.

The Battle

The army that Charles amassed was probably some 30,000 men,

a mixture of professional soldiers whom he had commanded in campaigns across

Gaul and Germany and a mixed lot of militia with little weaponry or military

skills. The Franks were hardy soldiers that armed themselves as heavy infantry,

wearing some armor and fighting mainly with swords and axes. How much the

Franks depended on cavalry has been disputed, for infantry had long dominated

the European battlefield, and cavalry was only at this time becoming common.

The strength of both infantry and cavalry was their determination in battle,

but their weakness was their almost complete lack of discipline. Further,

Charles lacked the wherewithal to maintain any sort of supply train, so his

army lived off the land.

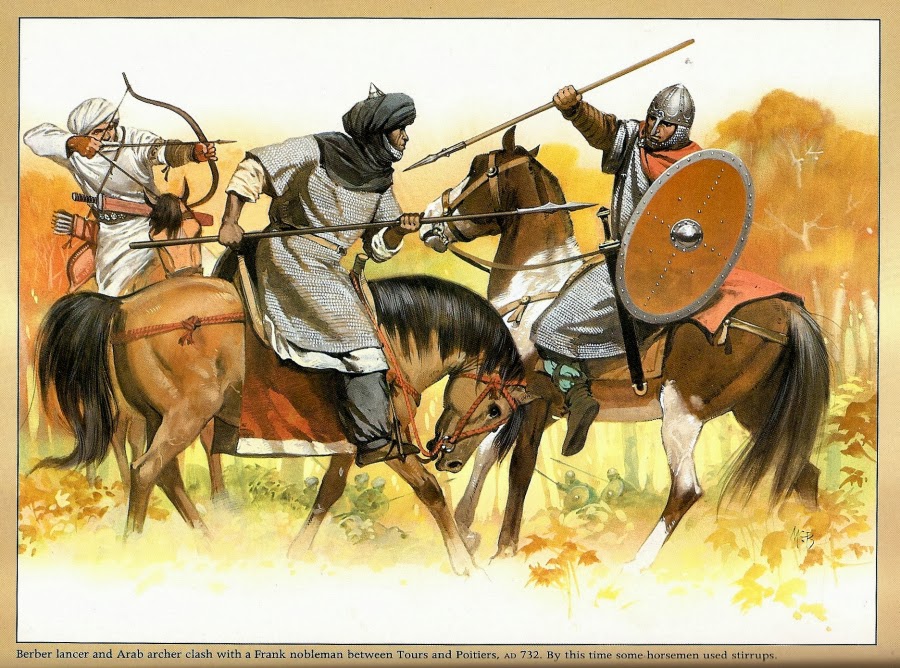

The army he marched to face was made up primarily of Moors

who fought from horseback, depending on bravery and religious fervor to make up

for their lack of armor or archery. Instead, the Moors fought with scimitars

and lances. Their standard method of fighting was to engage in mass cavalry

charges, depending on numbers and courage to overwhelm any enemy; it was a

tactic that had carried them thousands of miles and defeated dozens of

opponents. Their weakness was that all they could do was attack; they had no

training or even concept of defense. They, like the Franks, lived off the land.

The two armies approached each other in the early autumn of

732. Abd er-Rahman’s army had succeeded in plundering many towns and churches,

and they were overwhelmed with their loot. They met in an unknown location

somewhere south of Tours, between that city and Poitiers. Abd er-Rahman was

surprised by the arrival of the Franks. Exactly how large the opposing forces

were is the point of much disagreement. The Moslem army is numbered by modern

writers as anywhere from 20,000 to 80,000, whereas the Frankish army has been

described as both larger and smaller than those numbers. Abd er-Rahman faced a

dilemma: to fight, he would have to abandon his loot, and he knew that his men

would balk at that order. Luckily for him, Charles did not attack, but merely

kept his distance and observed the Moslems for about a week. Abd er-Rahman used

that break to send men south with the loot, where they could recover it after

they beat the Franks. In the meantime, Charles was awaiting the arrival of his

militia, whom he used primarily as foragers for his fighting men and less as

fighters themselves.

After 7 days of waiting, watching, and certainly a bit of

probing by both sides, Abd er-Rahman felt his loot sufficiently safe to focus

on the battle. The exact date of the battle is unknown, although some sources

(Perrett, The Battle Book) name 10 October. Charles knew the nature of the

Moslem fighting style, and he had just the troops to counter it. As the Moslems

massed to launch their charge, Charles formed his men into a defensive square

made up primarily of his Frankish followers, but supplemented with troops from

a variety of tribes subject to the Franks. No detailed account of the battle

exists, but later reports relate that the Moslem cavalry beat unsuccessfully

against the Frankish square, and the javelins and throwing axes of the Franks

inflicted severe damage on the men and horses as they closed. The Moslems,

knowing no other tactic, continued to attack and continued to fail to break the

defense. Isidorus Pacensis wrote staunch Frankish square: “The men of the North

stood motionless as a wall; they were like a belt of ice frozen together, and

not to be dissolved, as they slew the Arab with the sword. The Austrasians

[Franks from the German frontier], vast of limb, and iron of hand, hewed on

bravely in the thick of the fight.” It was this display of strength that earned

for Charles his nickname Martel, or “the Hammer.” Eudo, fighting with Charles,

led an attack that turned the Moslem flank; they either panicked or feared for

their loot. Creasy (Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, p. 166) quotes a

Moslem source: “But many of the Moslems were fearful for the safety of the

spoil which they had stored in their tents, and a false cry arose in their

ranks that some of the enemy were plundering the camp; whereupon several

squadrons of the Moslem horsemen rode off to protect their tents.” The

departure of some of the cavalry apparently had a bad effect on the rest, and

the Moslem effort collapsed.

At day’s end, the Moslems withdrew toward Poitiers. Charles

kept his men together and did not pursue, thinking that the battle would resume

the following day. In the night, however, the Moslems learned that Abd

er-Rahman had been killed in the fighting, so they fled. When the Franks found

the Moslem camp empty of men the next morning, they contented themselves with

recovering the abandoned loot. No accurate casualty count for either side was

recorded.

Results

Survivors of Abd er-Rahman’s army retreated back toward

Spain, but they were not the last Moslems that ventured across the Pyrenees in

search of easy wealth. They were, however, the last major invasion. Pockets of

Moslem power remained along the southern frontier and Mediterranean coast until

759, but, for the most part, Islam settled into Spain and went no farther.

Although the effectiveness of Charles Martel’s tactics was certainly a factor,

it was internal struggles within Islam that limited continued expansion. When

factional fighting broke out in Arabia, the effects spread throughout the

Moslem empire. This not only divided the fighting forces, it also isolated the

Moslem occupants in Spain from any religious leadership from the Middle East.

Thus, consolidation seemed preferable to expansion.

Had the Moslems been victorious in the battle near Tours, it

is difficult to suppose what population in western Europe could have organized

to resist them. On the other hand, Abd er-Rahman’s force was rather limited,

and the religious schism that flared soon after the battle could well have

stopped his campaigning as effectively as did the Franks. Thus, whether Charles

Martel saved Europe for Christianity is a matter of some debate. What is sure,

however, is that his victory ensured that the Franks would dominate Gaul for

more than a century. For a couple of centuries, the ruling Merovingian dynasty

had produced young, weak kings that ceded much of their ruling power to men who

held the position of majordomo, or mayor of the palace. As the representative

from the king to the aristocracy, the majordomos were able to coordinate public

activity more than order it. By the time of Pepin II, however, the role of the

majordomo was virtually indistinguishable from that of the king, and the

monarch ruled in name only. Indeed, Charles was majordomo without a king, and

upon his death in 741 his sons claimed kingship and divided the realm between

them. During this same period, the aristocrats began exercising hereditary

rights to their lands, rather than receiving their positions at the king’s

pleasure. This was the start of the feudal era, which dominated European

society for centuries. To exercise control over these aristocrats, Charles

Martel also granted land in payment for military service rendered, but to

acquire that land he had to take it from the greatest landowner, the Catholic

Church. That earned him the displeasure of Rome, but similar actions on the

part of Charles’s grandson actually brought the military power of the Franks

and the religious authority of the church closer together. His grandson was

also called Charles, later termed “the Great,” or Charlemagne. Under his rule,

the Franks rose to their greatest power both politically and militarily.

The nature of the European military changed after this

battle. The concept of heavy cavalry was forming in the eighth century. The

introduction of the stirrup made stability on horseback possible, and stability

was vital for both carrying an armored rider and using heavy lances. The age of

the armored knight, a fighting machine that was both the result and the

foundation of feudalism, was being born. Although infantry remained key to

winning European battles, it was paired with or subordinated to cavalry from

this point until the fifteenth century.

Thus, the establishment of Frankish power in western Europe

shaped that continent’s society and destiny, and the battle of Tours confirmed

that power.

References:

Creasy, Edward S. Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World. New

York: Harper, 1851; Dupuy, R. Ernest, and Trevor Dupuy. Encyclopedia of

Military History. New York: Harper & Row, 1970; Fuller, J. F. C. A Military

History of the Western World, vol. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1954;

Gregory of Tours. History of the Franks. Translated by Ernest Brehaut. New

York: Columbia University Press, 1916; Oman, Charles. The Art of War in the

Middle Ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1953 [1885].