Meanwhile, German counter-attacks failed to retake Kiev but

did push the Soviets out of Zhitomir, where the 1 Ungarishe Jabostafel found a

new base and celebrated its 100th kill in December 1943. Through long months of

intense combat, it had suffered the loss of just 6 pilots (plus 2 missing) from

an original 37 airmen, as proof of their great skill and good luck. After New

Year’s 1944, they relocated yet again, this time to Khalinovka. During the

transfer, Lieutenant Lasl6 Molnar and his wingman, Corporal Erno Kiss, encountered

30 Shturmoviks covered by 10 Lavochkins. Laughing at the 20-to-1 odds against

them, the Hungarians dove amid the enemy bombers, shooting down four of them,

plus two Red fighters, before completing their flight to Khalinovka.

While battles such as these showcased the Hungarians’ superb

combat performance, they nonetheless demonstrated the awful numerical edge

overshadowing the Eastern Front in lengthening shades of doom. The sheer mass

of man power and materiel now at Stalin’s disposal was sufficient to usually

drown any technological superiority the Axis might have possessed, as evidenced

by the 2,600 warplanes he assembled for his conquest of Vinnitsa, the

Wehrmacht’s own headquarters in Russia, defended by 1,460 Luftwaffe aircraft.

The Soviets were nevertheless stymied for more than three months, during which

the entire Eastern Front was stabilized, and the Pumas were in the thick of the

fighting, scoring more than 50 “kills” in January and February alone.

On March 17,1944, the USAAF for the first time attacked

Budapest with 70 B-24s. The Liberators were undeterred by just four Hungarian flown

Messerschmitts, all of which were damaged and two shot down by the unescorted

heavy-bombers’ defensive fire. The encounter illustrated not only the pitifully

inadequate numbers of aircraft available for home defense but lack of proper

pilot training. The Americans returned on April 3 to bomb a hospital and other

civilian targets as punishment, it was generally believed, for the recent

establishment of a new government closer aligned with Germany. In any case, the

attack left 1,073 dead and 526 wounded.

During the 13-day interval between these raids, the 1/1 and

2/1 Fighter Squadrons had been reassigned to the capital, and its crews

provided a crash course in interception tactics. Even so, 170 P-38 Lightnings

and P-51 Mustangs prevented most of the two dozen Pumas from approaching their

targets. A few that penetrated the escorts’ protective ring destroyed 11

heavy-bombers at the cost of 1 Hungarian flyer. Six more Liberators were

brought down by Budapest flak. In another USAAF raid 10 days later, the

Mustangs were replaced by Republic P-47s, which failed to score against the

Messerschmitts. Instead, two Thunderbolts fell to ground fire, along with four

B-17 Flying Fortresses.

Meanwhile, the Hungarian pilots were getting the hang of

interception, suffering no casualties for downing eight B-24s and six

Lightnings. These losses combined with the mistaken American belief that

aircraft manufacturing throughout Hungary had been brought to a halt. In fact,

just a small Experimental Institute lost its hangars and workshops, and a

Messerschmitt factory was damaged, although soon after restored to full

production capacity. USAAF warplanes continued to appear in Hungarian skies

over the next two months, but only on their way to targets in Austria or

ferrying supplies to the Soviet Union. The Magyar Legierd took full advantage

of this lull in enemy raids to upgrade and re-train three, full-strength

fighter squadrons, while Budapest’s already formidable anti-aircraft defenses

were bolstered.

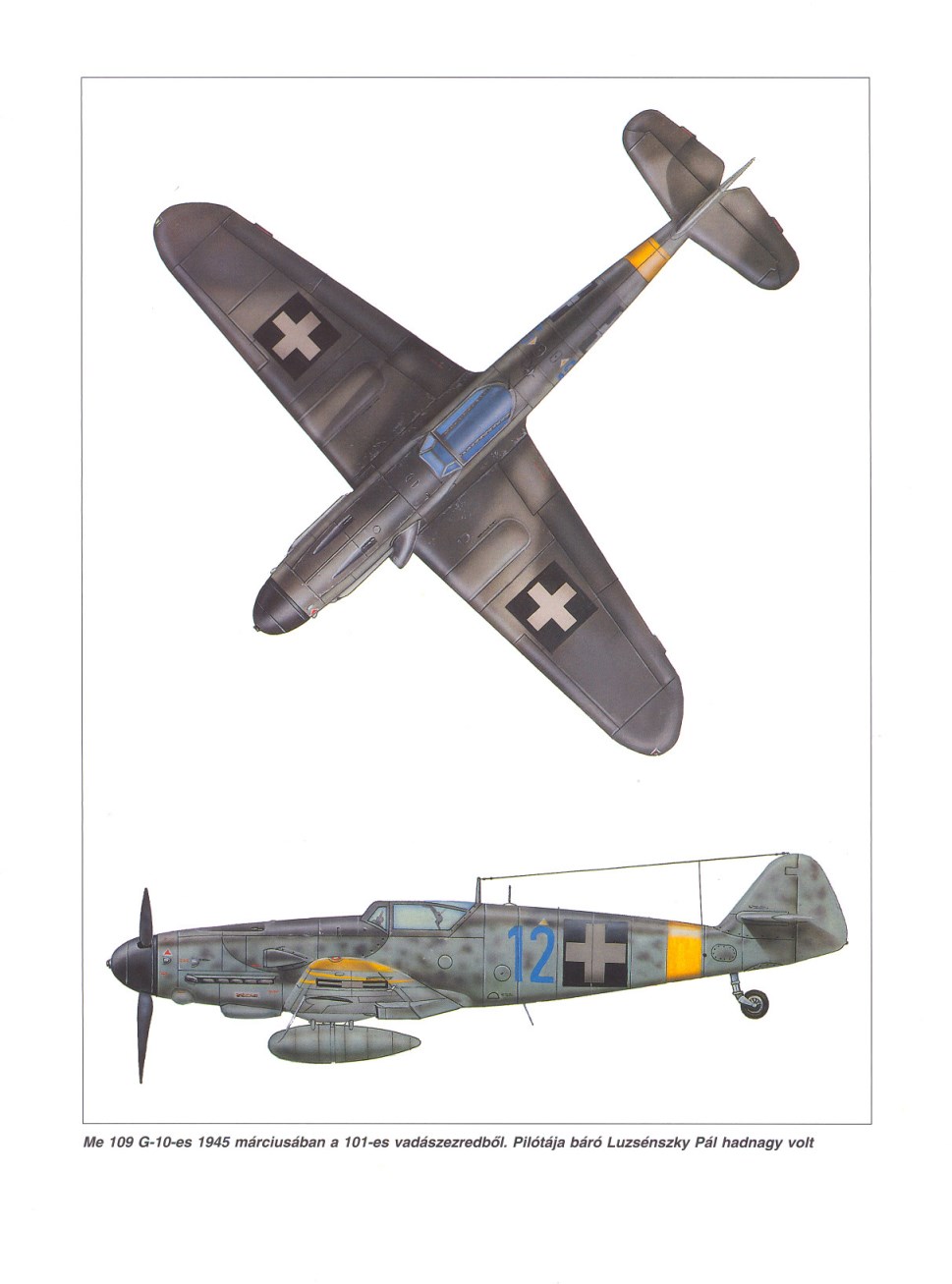

When the 101. Honi Legvedelmi Vadkszrepiild Osztkly, or

101st “Puma” Fighter Group, was formed on May 1, 1944, Cadet Dezsd

Szentgyorgyi transferred to the 101/2 Retek, “Radish” Fighter Squadron,

where he would soon become Flight Leader, then, on November 16, Ensign. These

rapid promotions were generated by his rapidly rising number of enemy

heavy-bombers shot down during the “American Season;’ as the period was

referred to by his fellow pilots. Placed in charge of the Home Defense Fighter

Wing was Major Aladar Heppes. At 40 years of age, he was the Magyar Legierd’s

eldest pilot, known as “the Old Puma;’ a seasoned Eastern Front veteran.

For practice, his airmen confronted several hundred USAAF heavy bombers and

their escorts droning toward Vienna on May 24. Although four Liberators, a

Flying Fortress and one Mustang were destroyed, Major Heppes lost one man

killed, and six Messerschmitts were damaged. But the Home Defense Fighter Wing

crews learned from their experience, and vowed to do better when the Yanks

returned in earnest.

Meanwhile, in preparation for imminent Soviet invasion of

their country, the “Coconut” Stuka crews were recalled from Eastern

Front duty to serve on Hungarian soil. Their 102/2nd dive-bomber squadron was

redesignated the 102/1st fighter-bomber squadron, indicating the transition

training they undertook to Focke-Wulf FW-190F-8s at Borgond airfield.

On the morning of June 14, 600 USAAF heavy-bombers and 200

escorts went after nitrogen plants and oil refineries outside Budapest, while

P-38 Lightnings made low-level strafing runs on a Luftwaffe squadron of

Messerschmitt Me.323 Gigant transports at Kecskemet airfield. The defenders

were joined by a quartet of German fighters, which made two “kills:’ Eight

more were claimed by the 32 Hungarian pilots, who lost one of their own. The

city’s anti-aircraft defenses once again proved their worth, shooting down 11

enemy intruders.

Only 28 Home Defense interceptors were serviceable 48 hours

later to oppose 650 heavy-bombers ringed by 290 Lightnings and Mustangs that

filled the skies over Lake Balaton. Despite the excessive odds confronting

them, the Pumas broke through the thick ranks of protective American fighters,

claiming a dozen of them to destroy four Liberators. A remarkable set of

“kills” was accomplished by Corporal Matyas Lorincz during this, his

first operational flight. Hot in pursuit of four P-38s, he was unable to

prevent them from shooting down Lieutenant Kohalmy. A moment later, Lorincz was

in firing range, and the two Lightnings he set afire collided with and brought

down a third. Lieutenant Lajos Toth, Hungary’s third highest-ranking ace with

26 “kills, was forced to take to his parachute, landing not far from the

U.S. pilot he had himself shot down a few minutes before. Aviation engineer

Gyorgy Punka, recorded how “they chatted until the American was picked up

by a Hungarian Army patrol”‘

Relations between opponents were not invariably cordial,

however, “with the American pilots deliberately firing on Hungarian airmen

who had saved themselves by parachute, or strafing crash-landed aircraft;’

according to Neulen. “One of the victims was Senior Lieutenant Jozef

Bognar, who was killed by an American pilot while hanging helplessly beneath

his parachute”‘

The June 16 air battle had cost the Home Defense Fighter

Wing the lives of five pilots, including two more wounded. Six Gustav

Messerschmitts were destroyed, and seven damaged. These losses were immediately

made good by fresh recruits and replacement planes, as the struggle against the

bombers began to reach a crescendo on the 30th. This time, the Pumas were aided

by 12 Messerschmitt Me-110 Destroyers and Me-410 Hornets, plus 5 Gustavs from

the Luftwaffe’s 8th Jagddivision. The Germans and Hungarians claimed 11

“kills” between them, while the ferocity of their interception forced

a formation of 27 bombers to turn back short of the capital; the remaining 412

diverted into the northwest.

The next USAAF attempt to strike Budapest’s area oil

refineries on July 2 was similarly spoiled by just 18 Pumas, together with a

like number of Luftwaffe Messerschmitts. As their colleagues in Germany had

already learned, it was not necessary to destroy an entire flight of enemy bombers

to make them miss their target. Among the most successful interceptions

undertaken by the Magyar Legier6 fighters was carried out against 800 U.S.

warplanes on July 7. A mere 10 Messerschmitts led by Major Heppes, the Old Puma

himself, accounted for as many Liberators falling in flames from the sky,

together with another 15 brought down by flak. One Gustav was lost, its pilot

parachuting safely to earth.

The American aerial offensive pressed on throughout the

summer and into fall of 1944 on an almost daily basis and in growing numbers.

The Home Defense Fighter Wing continued to score “kills” and deflect

bomber missions, until its men and machines were withdrawn from around Budapest

in mid-October on more immediately pressing business: the invasion of their

country. The previous six months of stiff Axis resistance had slowed, but could

not halt the Red Army juggernaut, which now reached the foot of the Carpathian

Mountains at the Hungarian frontier.

In the midst of this crisis, Admiral Horthy lost his nerve

and attempted to capitulate to the Soviets. But the Germans learned of it in

time, and placed him in protective custody for the rest of the war. News of his

dethronement was met with a mix of indifference and acclaim, because the

Hungarian people, who remembered all too well the Communist tyranny and terror

they experienced during the 1920s, preferred resistance to submission. The Red

Army was stopped at the Eastern Carpathian Mountains by German-Hungarian

forces, but they could not simultaneously contain a veritable deluge of Red

Army troops that overran Transylvania.

Their attack on Budapest began in early December, although

the capital was not easily taken. Russian losses over the previous

three-anda-half years were becoming apparent in the declining quality of

personnel on the ground and in the air. When, for example, a formation of

Heinkel He.111 medium-bombers escorted by Hungarian pilots of the 101/2 Fighter

Squadron was about to sortie against Soviet troops crossing the Danube on

December 21, an out-numbering group of Lavochkins scattered and fled without a

fight. Clearly, Stalin was relying on the dead weight of numbers more than ever

before to achieve his objectives.

On January 2,1945, a joint German-Hungarian effort known as

Operation Konrad I was launched to break the siege of Budapest. Although

significant gains were made early and the Pumas wracked up more “kills;’

high winds kept flying to a frustrating minimum and destroyed more of their

aircraft than Soviet pilots. After three days, the attempt to liberate the

capital bogged down. Undaunted, reserves pushed onward with Operation Konrad

II. During a rare stretch of clear weather on the 8th, Hungarian crews of the

102 Fast Bomber Group celebrated their 2,000th sortie by pummeling Red Army

positions. The return of dense fog grounded further flights, however, and

Operation Konrad II was abandoned the next day, mostly for lack of air support.

A third and final Operation Konrad appeared to succeed where

its predecessors had failed. The Vlth German Army kicked it off on January 18,

and 35 miles of territory were recaptured in the first 48 hours of the attack.

The mighty Soviet 17th Air Army stumbled backward across the Danube, which

advancing Axis troops reached on the 20th. Two days later, the Russians

evacuated Szakesfehervar. These successes on the ground were importantly aided

by airmen such as Ensign Dezso Szentgyorgyi, the Magyar Legier’s leading ace,

who scored 14 victories alone in the fighting for Budapest. His and the rest of

the Pumas’s chief targets were Shturmovik ground-attack planes, together with

enemy armored vehicles and troops.

A few survivors of the 102/2 Dive-bomber “Coconut”

Squadron most of its Ju-87Ds had been destroyed on the ground at Bdrgond the

previous October 12 by low-flying P-51s of the American 15th Air Force-pounded

Red Army positions and knocked out T-34 tanks. Their vital sorties were

abruptly curtailed from January 23 by heavy snowfall, just when Soviet reserves

began entering the battle area, and more than 300 German tanks were destroyed.

Three days later, Operation Konrad III had to be canceled. During these

repeated, all-out efforts to liberate Budapest, the three participating Magyar

Legiero squadrons had flown some 150 combined missions to win 69 aerial

victories for the loss of 6 pilots during 20 days of flight allowed by the

weather. The “Coconut” Squadron was finished, having flown 1,500

sorties, dropped 750 tons of bombs, for the loss of half of their commissioned

officer pilots and 40 percent of noncommissioned pilots.

An even-more ambitious attempt than Operation Konrad to

regain the initiative got underway on March 6 with Operation Fruhlingserwachsen

(“Spring Awakening”) in the Lake Balaton area of Transdanubia. Forces

included the German 6th SS Panzer Army, the 1.SS Division Leibstandarte Adolf

Hitler, German 2nd Panzer Army, Army Group Balck, elements of German Army Group

E, and the Hungarian Third Army. Objectives included saving the last oil

reserves still available to the Axis and routing the Red Army long enough to

recapture Budapest. Combined Luftwaffe and Magyar Legiero forces amounted to

850 aircraft opposed by 965 Soviet warplanes.

Odds against the Axis on the ground were far more loaded in

their opponents’ favor, with seven infantry armies and a tank army. The

combined 101/1 and 101/3 Fighter Squadrons strove to stave off massed flights

of Bostons and Shturmoviks savaging Axis armored units and troop

concentrations. High numbers of either type were shot down, together with

several Yak-9s, on March 9, when the Pumas completed 56 sorties, to gain

temporary air superiority above the German 6th SS Panzer Army, enabling it to

advance. Despite early, impressive gains such as these, Germany’s last

offensive could not prevail against the enemy’s overwhelming numerical

advantage, and Axis troops were compelled to fall back to their prepared

positions in Hungary, where they were soon overrun.

When the Soviets began their drive across the Austrian

border, Magyar Legiero-flown Gustavs shot up infantry columns, cavalry corps,

truck convoys, and horse-drawn wagons clogging the roads to Vienna in low-level

runs throughout April 3. Fierce ground fire claimed 8 Pumas and destroyed 10 of

their aircraft. Replacements of both men and machines arrived almost

immediately, but their operations were restricted by a serious fuel shortage.

In spite of this crisis, they continued to shoot down both Soviet Lavochkins

and American Mustangs, although their primary focus was strafing and bombing

the endless torrent of Soviet troops and equipment flooding into Austria. A

Yak-9 Lieutenant Kiss, already an ace with five “kills;’ shot down on

April 17, 1945, was the Hungarians’ final aerial victory. They went on to fly

throughout the month, blasting Soviet vehicles, troops, and supplies.

On May 4, as American soldiers approached the airfield at

Raffelding, remaining warplanes of the Magyar Legier6, sabotaged by their own

crews, exploded into flames. Their self-immolation represented the undefeated

Pumas’s ultimate act of defiance.

Long before these climactic events, in early 1938, the first

Hungarian airborne unit had been formed at Szent Endre, an island in the Danube

River, near the capital city of Budapest. The Ejtoernyos (paratroopers)

attracted many volunteers, although their equipment was at first entirely

foreign made. The cadets jumped with Italian Salvadore, German Schrodor, and

American Irving parachutes from Italian Caproni 101 transport aircraft. Powered

by three Alfa Romeo, license-built Armstrong Siddeley Lynx engines rated at 200

hp apiece, the reliable, sturdy, high-wing monoplanes could accommodate eight

paratroopers each.

By the following year, the Hungarian Army had developed its

own, locally manufactured airborne equipment, including knee and elbow pads,

jump smock, and H-39M parachute. The doughty Caproni veterans of the Ethiopian

War were replaced by the much-larger SavoiaMarchetti SM-75. The huge

Marsupiale, “Marsupial;’ with its 1,276.14 square feet of wing area, was

capable of carrying 25 paratroopers. After relocating to the Papa Airport, the

Ejtoernyos consisted of 30 officers, 120 NCOs, and 250 enlisted men in one

battalion of three companies.

Their baptism of fire was a limited invasion of Yugoslavia

to reclaim territories severed from Hungary after World War I by Allied framers

of the Versailles Treaty. The Ejtoernyos made their first combat jump on April

12, 1941, over the northern Yugoslavian district of Delidek. From there, they

marched more than 18 miles under cover of darkness to surprise the defenders of

several bridges, which were swiftly taken after brief fighting. That same day,

the paratroopers suffered a grievous loss in an accident that took the lives of

22 comrades and their first commander, Major Arpad Bertalan, when the

overloaded Marsupiale in which they were flying crashed at Veszprem airfield.

Thereafter, the unit was known as the “Bertalan Battalion;’ led by Colonel

Zoltan Szugyi.

The Ejtoernyos participated in numerous actions on the

Eastern Front, most notably in the relief of Hungarian troops during the

struggle for Stalingrad. During March 1944, the paratroopers were part of Axis

efforts to shore up the southeastern flank in danger of collapse caused by

Romania’s defection to Stalin. Colonel Szugyi and his men established a strong

defensive perimeter in the Carpathian Mountains, the last natural emplacement

of its kind in the East. Warriors of the hard-pressed Bertalan Battalion held

their positions against 10-to-1 odds, suffering many casualties, but repeatedly

frustrated the combined Russian-Romanian offensive long enough for regular

German and Hungarian troops to withdraw with their weapons and equipment in

good order.

Ejtoernyos survivors re-grouped on October 20 with two other

light infantry battalions in the understrength St. Laszlo Division, named after

the victorious medieval king, Saint Ladislas I. It was commanded by Zoltan

Szugyi, who had been promoted to General for his exemplary defense of the

Carpathian Mountains. In November, the St. Laszlo Division transferred to the

Lake Balaton area, where, after fruitlessly trying to stem the Red Army tide

for 10 days, the paratroopers and their comrades pulled back to defend the

Hungarian capital. By December 1, they were surrounded in Budapest by the

Soviets, but broke through enemy lines before the city capitulated on February

12, 1945.

Ejtoernyos remnants still fought cohesively as a unit,

retreating into Austria, until the last day of the war, when General Szugyi

surrendered with a handful of survivors to the British Army on May 10 to escape

capture by the Russians. Instead, they were all placed under arrest and

transported to the East. Lieutenant-General Szombathelyi, Commander in Chief of

the Hungarian Army during 1941, had been similarly turned over to Communist

authorities in Belgrade, where, after a well-publicized show trial, was

executed by impalement. General Sziigyi’s death sentence was commuted to life

imprisonment only after he had been sufficiently tortured into a fulsome

confession. Meanwhile, his paratroopers disappeared behind the Iron Curtain

that fell over Hungary for the next 43 years.

On April 16, 1945, two weeks before the close of

hostilities, Dezsd Szentgyorgyi destroyed the last of his 32 confirmed

victims-an Ilyushin 11-4 bomber-making him Hungary’s leading ace. Such skills were

not only reflected in his aerial victories: during the course of more than 220

sorties, he was never shot down, nor ever crashed under any circumstances.

After the war, he flew as a commercial pilot for MASZOVLET, Hungarian-Soviet

Airlines, from 1946 until 1949, but was arrested the following year for his

past association with the criminalized Magyar Legiero.

His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, but he

was freed during the Budapest Uprising of 1956. Following its blood-stained

suppression, the new Soviet authorities, not wishing to further antagonize

their restive subjects, dismissed all charges against Szentgyorgyi and allowed

him to resume his aviation career with the renamed Malev Hungarian Airlines.

Over the next 15 years, he logged 12,334 flight hours over more than three

million miles, dying on August 28, 1971, in his one and only crash near

Copenhagen, less than three weeks short of his retirement. The aircraft in

which he died had been built by the same company that made his final victim of

World War II-Ilyushin.

Today, the Hungarian armed forces at Kecskemet operate the

59th “Szentgyorgyi Dezso” Air Base.