Ninth War of

Religion, (1589–1598)

PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Catholics vs. Huguenots in France

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): France

DECLARATION: None

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: The Protestants in France

sought religious freedom.

OUTCOME: Henry III, although he had returned to the Catholic

faith, issued the Edict of Nantes, which proclaimed religious freedom for

French Protestants.

APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS: Catholics,

26,000; Huguenots, 20,000

CASUALTIES: Catholics, 13,550 killed or wounded; Huguenots,

12,040 killed or wounded

TREATIES: Edict of Nantes (1598)

The naming of Henry of Navarre (1553–1610) as successor to

the French throne sparked the final War of Religion between Protestant

Huguenots and Catholics in France. Insisting that Charles, duke de Bourbon

(1566–1612), was the rightful successor to Henry III (1551–89), the Catholics

enlisted the aid of the Spanish. Charles, duke of Mayenne (1554–1611), the

younger brother of Henry of Guise (1555–88), led the Catholic efforts.

At the Battle of Arques on September 21, 1589, Henry of

Navarre (1553–1660) ambushed Mayenne’s army of 24,000 French Catholic and

Spanish soldiers. Having lost 600 men, Mayenne withdrew to Amiens, while the

victorious Navarre, whose casualties numbered 200 killed or wounded, rushed

toward Paris.

A Catholic garrison near Paris repulsed Navarre’s advance on

November 1, 1589. Not to be daunted in his quest for the throne, Henry withdrew

but promptly proclaimed himself Henry IV and established a temporary capital at

Tours.

Henry of Navarre won another important battle at Ivry on

March 14, matching 11,000 troops against Mayenne’s 19,000. Mayenne lost 3,800

killed, whereas Navarre suffered only 500 casualties.

Civil war continued unabated. Between May and August 1590,

Paris was reduced to near starvation during Navarre’s siege of the city.

Maneuvers continued, especially in northern France until May 1592; however, in

July 1593 Henry of Navarre reunited most of the French populace by declaring his

return to the Catholic faith. His army then turned to counter a threat of

invasion by Spain and the French Catholics allied with Mayenne.

On March 21, 1594, Henry of Navarre entered Paris in triumph

and over the next few years battled the invading Spanish: at Fontaine-Française

on June 9, 1596, at Calais on April 9, 1596, and at Amiens on September 17,

1596. No further major campaigns ensued.

On April 13, 1598, Henry of Navarre ended the decades of

violence between the Catholics and the Protestants by issuing the Edict of

Nantes, whereby he granted religious freedom to the Protestants. Then on May 2,

1598, the war with Spain ended with the Treaty of Vervins, whereby Spain

recognized Henry as king of France. The next major conflict between the

Catholics and Protestants in France occurred 27 years later when the

Protestants rose in revolt in 1625 and the English joined their cause in the

ANGLO-FRENCH WAR (1627–1628).

As with any civil war the sudden mustering of large numbers

of infantry means the quality generally drops. There were however, aside from

the Swiss, some excellent infantry out there that was indeed decisive.

First, there was the ‘Spanish’ infantry regiments, composed

of separate nationalities of the Spanish Empire. The Spanish and the Italians

were best, followed by Burgundian and Walloon. It was they that crushed the

Dutch in so many battles and saved their French Catholic allies at others.

The French had their ‘Legion’ infantry from different

quarters of the country. Some were recently raised while others like the Bande

Noire were initially veteran companies of from the late Italian wars who were

excellent. Also, the garrisons of the three bishoprics gained from the Holy Roman

Empire were considered the best soldiers in France.

Even the Huguenots had their crack infantry regiments, like

those under La Noue in Poitou that were long service veterans (by 1570) and could

stand up to the best of the Legions. Navarre’s infantry in the 1580’s were very

tough veterans as they proved at Coutras and later north of the Loire allied to

Henry III.

The Papacy sent some fine infantry to France in 1568 which

were feared because of their discipline and excellent officers, and were in the

thick of the fighting.

Regiments that were long service and well equipped could be

and were decisive (especially in Sieges, of course) on the battlefields of

Dreux, St. Denis, Moncontour and Coutras. There were dozens of less famous (but

fairly large) battles where they took the lead.

Hastily raised regiments were generally of very low quality

and were mostly good for running away. The Huguenots who were pike-and-corslet

poor would strip some units to supply others, leaving them only with staves and

arquebus. They were usually kept far to the rear in battle.

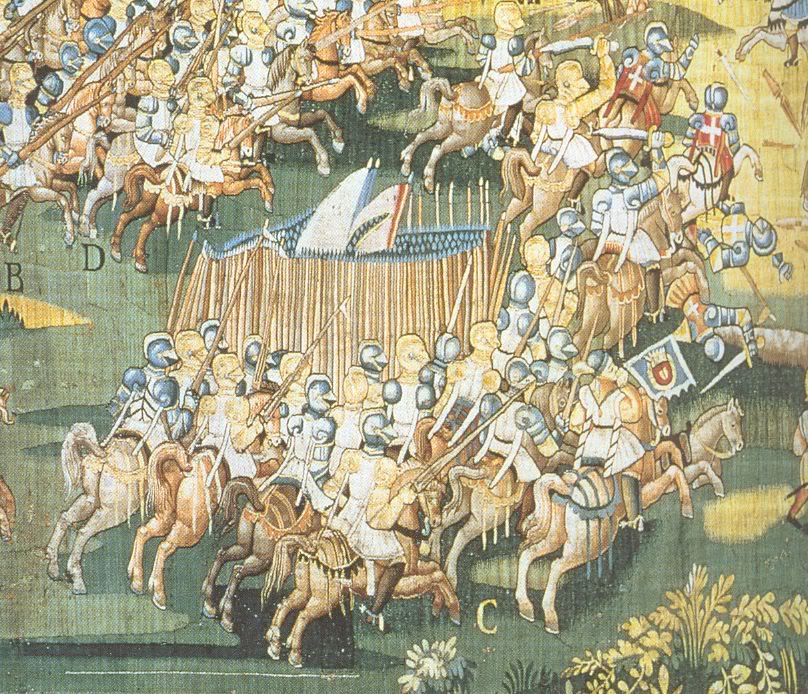

It should be remembered that France fielded the best cavalry

in Europe and therefore had pride of place. Much of the war was financed by the

wealthy and as you can guess they lavished money on their Gendarmes companies

before they took care of the infantry. The crown could afford (on credit) to

keep infantry embodied and armed so they were of better quality.

Infantry played an important part in several battles of the

French wars but this tends to get overlooked due to a focus on the cavalry or a

lack of details in English language descriptions which often rely heavily on

Oman. And Oman used a narrow selection of sources while turning a blind eye to

facts which did not suit him. As a result his battle descriptions are inferior

in detail and quality when compared to those of French or German historians.

Dreux 1562

The Swiss infantry are rightly famous for their stout resistance in this

battle. Despite all of their supporting troops being overthrown and routed and

the lack of support from the other half of the Royal army they fought on

resisting attacks by both horse and foot. But even though the Landsknechts were

easily beaten by the Swiss they could not stand up to the repeated &

skillfull attacks made by the Huguenot Gendarmes, Reiters and skirmishing

Enfants Predu. With most of the Swiss senior officers killed or wounded and a

good part of the rank & file dead and wounded the mighty Swiss regimental

square broke apart as it was attacked from almost every direction. But the men

did not rout, rather they banded together around individual standards and in

small bands made fighting withdrawal from the field.

During the Duke of Guise’s counterattack the veteran Gascon

infantry play a critical role as they resisted all attacks by the Huguenot

Gendarmes even though they became completely surrounded during the Huguenot

charge. Their resistance tied up a lot of cavalry and eased the pressure

against the rest of the catholic army which was taking a beating from the

combined attack of Gendarmes & Reiters.

Just before that the Spanish infantry had made short work of

the Huguenot foot which forced the Admiral to attack without infantry support.

Without the actions of the Swiss & Gascon infantry it is

probable that the Royalists would have lost the battle of Dreux. Their cavalry

clearly came second best in most of the actions when fighting on their own.

Moncontour 1569

The Swiss again played a very important part in the battle, two regiments took

part. Cléry’s weaker regiment was deployed in the Vanguard with strong support

by French arquebusiers who were posted on each flank. (In order to avoid a

repeat of Dreux where the Swiss lack of arquebusiers meant that they could not effectively

resist the Huguenot Reiters & Enfants Perdu). In the Main Battle Pfyffer’s

regiment was also supported by two ‘regiments’ of French shot, in addition the

cavalry of de Cossé was also tasked with protecting Pfyffer’s flank

In the battle Clery’s regiment engaged the Huguenot

Landsknechts, Segesser describes the ensuing combat as “hard fought and

“for quite some time undecided”. Pfyffer’s regiment remained in

reserve in the beginning but the battle reached a crisis point with the defeat

of Anjou’s cavalry and the death of the Markgraf of Baden Tavannes sent Pfyffer’s

Swiss into battle together de Cossé’s cavalry. The Swiss advanced rapidly

(“at a trott”), an attack against their flank by 1500 Reiters was

defeated by their supporting French arquebusiers and the disordered Reiters

were then routed by Royal cavalry. Meanwhile the Pfyffer’s men smashed into the

cavalry melee at a run and decided it for the Royalists. The Landsknechts who

so far had put up stout resistance was disordered by fleeing Huguenot cavalry

and then broken and massacred by Clery’s Swiss and their supporting troops.

Meanwhile Pfyffer had wheeled his regiment against the right wing of the Huguenot

army and effortlessly broke the resistance of the Huguenot’s infantry.

Arques 1589

Arques was very much an infantry battle but since Sully’s account is one of few

easily available in English and he fought with the cavalry the cavalry’s part

of the battle tend to get exaggerated. But it was the Swiss & French

infantry who held the critical fortified positions and without their ability to

resist superior numbers or willingness to counterattack to regain lost

positions Henri IV would have lost the battle.

Other battles

Battles like Coutras 1587 may not have been decided by the infantry but saw

extensive fighting between the infantrymen on both sides who were anything but

passive spectators. I suspect that a detailed look at the smaller and less well

known battles may well turn up similar details. The only battles in which the

infantry seems to have remained mostly passive seem to be St. Denis 1567 and

Ivry 1590 and even there I suspect that one might find that the infantry saw

more action that is commonly believed if one digs deep into the sources.