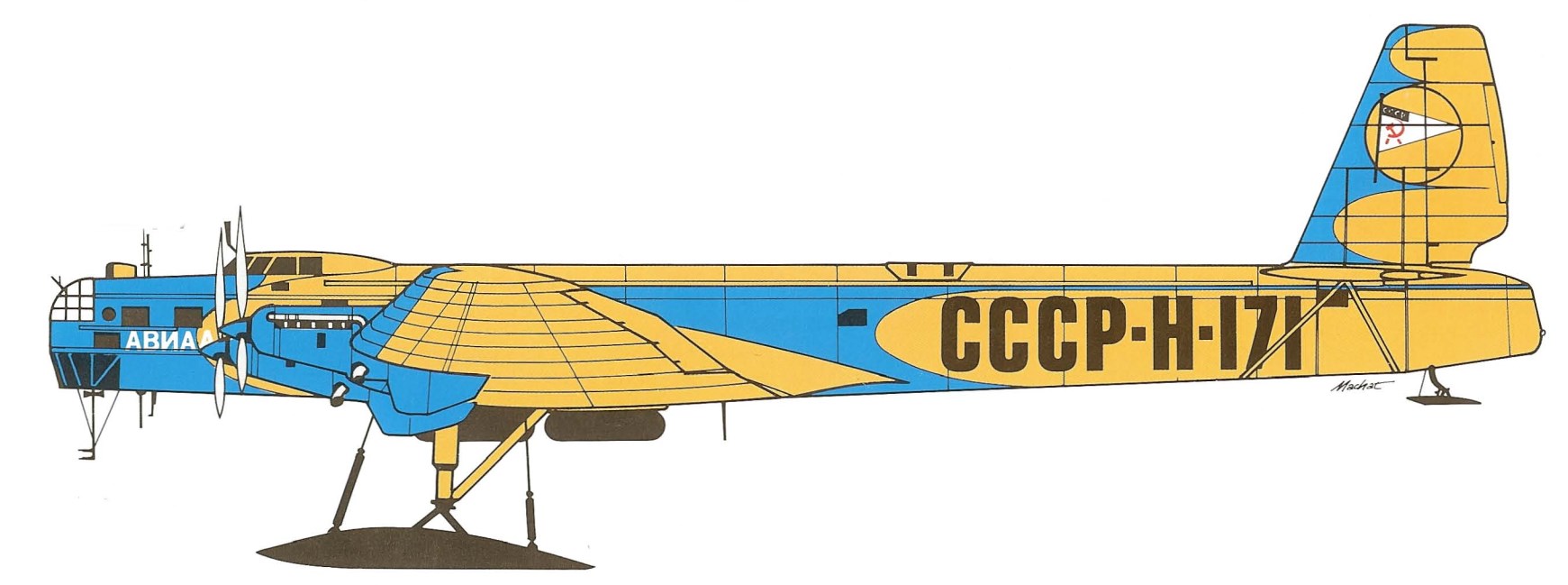

AM-34RN (4 X 970hp) – MTOW 22,600kg (49,8201b) – Normal Range 1,350km (840mi) – 12 SEATS. 180km/h (112mph). A special feature in the design was a tunnel that permitted air mechanics to crawl along the whole length of the wing, to inspect fuel tanks and cargo holds; and on one notable occasion, this was used to perform some unusual maintenance on one of the engines.

A Great Airplane

Bill Gunston, renowned technical aviation authority and

compiler of encyclopedic volumes about aircraft, including a masterpiece on

Soviet types, says this about the Tupolev-designed ANT-6, also known as the

TB-3 or the G-2: “This heavy bomber was the first Soviet aircraft to be

ahead of the rest of the world, and one of the greatest achievements in

aviation history” and that, “the design was sensibly planned to meet

operational requirement and was highly competitive aerodynamically,

structurally, and in detail engineering.” This was in 1930.

A Big Airplane – and

Plenty of Them

Give or take a ton or two, depending on the version, the

ANT-6 weighed, fully equipped for take-off, about 22 tons. Most G-2s weighed

22,050-kg (48,500-lb). By comparison, the contemporary German Junkers-G 38

weighed 24 tons, but only two were built, compared with no less than 818

ANT-6s. Of these, the vast majority were for the Soviet Air Force, painted dark

green, with sky blue undersides; about ten or twelve ANT-6s were allocated to

Mark Shevelev’s Polar Aviation (Aviaarktika), and painted in the orange-red and

blue colors. The four special versions prepared for the Papanin expedition,

according to Tupolev historians, were in bare metal, probably to save precious

weight. The British and French industries had nothing in the same league, and

the U. S. A. had not yet thought of the B-17.

A Versatile Airplane

Too Designed primarily as a bomber, the type was adapted for

other purposes. Design started way back in May 1926, wind tunnel testing was

completed in March 1929, and Mikhail Gromov made the first test flight on 22

December 1930. Throughout its lifespan (production ceased early in 1937) it

underwent many improvements, culminating in the ANT- 6A, specially modified for

Dr Otto Schmidt’s Aviaarktika’s assault on the North Pole; and it was also used

during the 1930s by Aeroflot, reportedly carrying as many as 20 passengers.

BREAKDOWN OF ANT-6 WEIGHT

Item Kilograms

Empty Weight on Skis 13,084

Radio and Navigation Equipment 297

Spare Parts and

Special Expedition Equipment 262

Crew of 8 (120kg each) 960

Provisions for crew (20kg each) 160

Gasoline 7,200

Oil 640

Total 22,603

(excluding cargo carried for ice station)

Weight Watchers

To equip the Papanin Expedition, every ingenious precaution

was taken to avoid superfluous weight. Tents were of light-weight silk and

aluminum. Utensils were of plastics or aluminum. The aircraft ladders were

convertible into sleds. Special equipment such as the sounding line and the

bathymeter were re-designed to save weight. Both the aircraft crews and the

members of the expedition were eternally grateful for the innumerable

contributions made by the ‘backroom boys’ in Leningrad, Moscow, and other

sources of equipment supply.

How Much Extra

To carry even this finely tuned total weight of nine tons,

divided between the four ANT-6 load-carrying aircraft, extra fuel also had to

be taken, in addition to the provisions listed in the tables on this page.

Almost two tons extra had to be carried by each aircraft. But the dome-shaped

airfield on the plateau at Rudolf Island offered shallow slopes, down which the

departing aircraft could gain speed and lift; and every item of nonessential

equipment was stripped from the interior, and every non-essential item of

personal effects was left behind.

Test Bombing

Landing a 24-ton aircraft on an ice-floe, no matter how big,

was a speculative proposition. It was determined that the minimum ice thickness

required was 70-cm (2-ft); engineers then devised a 9.5-kg (21-lb) ‘bomb’. It

was shaped like a pear and fastened at its rear or trailing end was a 6-8-m (20-ft)

line with flags attached. If the ice was less than 70-cm, the ‘bomb’ went

straight through. If more, it stuck, and the flags, draped on the ice,

indicated that landing was possible. This method was first utilized on the

Papanin expedition.

The North Pole

The Preparations Aviaarktika had already reached ever

northwards during the late 1920s and had spread its wings far and wide across

the expanses of the Soviet Union, in those areas where Aeroflot had no reason

to go, for lack of people to carry in a vast mainly frigid region that was

almost completely unpopulated, except for isolated villages and outposts.

Rather like expeditions on the ground, such as those to the South Pole, Otto

Schmidt, assisted by his deputy, Mark Shevelev, pushed further beyond the

limits, very methodically.

The northernmost landfall in the Soviet Union is the tiny

Rudolf Island, an icy speck on the fringes of the island group known as Franz

Josef Land (named after an Austrian explorer). At a latitude of 820 North,

Rudolf is only about 1,300km (800mi) from the Pole and a good location for a

base camp and launching site. Access to Franz Josef Land, while hazardous

because of the severe climate and terrain, is feasible as the twin-island

territory of Novaya Zemlya accounts for about 800km (500mi) of the distance

from the Nenets region.

On 29 March 1936, Mikhail Vodopyanov set off with Akkuratov

in a two-plane reconnaissance of the possible air route to Rudolf Island.

Flying blind for much of the time, and having to contend with inconveniences

such as boiling six pails of water before starting the engines with compressed

air, they reached their destination, and reported that the conditions, while

not ideal, were not impossible. On his return to Moscow on 21 May, Schmidt was

sufficiently satisfied to make plans. He arranged for the ice-breaking ship

Rusanoll to carry supplies to Rudolf, appointed Ivan Papanin to lead the

assault on the Pole, and selected a combination of four ANT-6 (G-2)

four-engined bomber transports, and one ANT-7 (G-l) twin-engined aircraft for

the task. Vodopyanov was to be the chief pilot.

The Assault

The working party sent to Rudolf did their work well. In

addition to setting up a base camp and a small airstrip on the shoreline, they

rolled out a longer runway, with a slight slope to assist take-off, on a

dome-shaped plateau about 300-m (I,000-ft) above the base camp. The squadron of

aircraft flew up from Moscow, leaving on 18 March 1937. Reaching Rudolf, they

began final preparations. The ANT-6s were estimated to need 7,300-liters (1,600-USg)

of fuel for the 18-hour round-trip to the Pole, and 35 drums were needed for

each aircraft. Ten tons of supplies of all kinds were to be taken, and

elaborate steps were taken to design light-weight and multipurpose equipment.

There were frustrating delays, as they waited anxiously for

Boris Dzerzeyevsky, the resident weather-man, to report favorable conditions,

and for Pavel Golovin, pilot of the ANT-7 reconnaissance aircraft, to confirm

Dzerzeyevsky’s forecasts, and to test the accuracy of the radio beacons. On one

flight, Golovin was stranded for three days when he had to make a forced

landing on the ice. But eventually, the expedition received the all-clear.

Flying an ANT-6 (registered SSSR-NI70), Mikhail Vodopyanov,

with co-pilot M. Babushkin, navigator I. Spirin and three mechanics landed at a

point a few kilometers beyond the North Pole (just to make sure) on 21 May

1937, at 11.35 a. m. Moscow time. Ivan Papanin, with scientists Yvgeny Federov

and Piotr Shirsov, together with radio operator Ernst Krenkel, immediately

established the first scientific Polar Station (PS-l) on the polar ice, on

which they eventually drifted on their private ice-floe in a southwesterly

direction until they were picked up off the coast of Greenland by a rescue ship

on 19 February 1938.

Their Tiny Hands Were

Frozen

During the final flight from Rudolf Island to the North Pole, Mikhail

Vodopyanov realized that one of the ANT-6’s engines was leaking water from its

radiator, with its precious anti-freeze liqUid disappearing into thin air.

Vodopyanov’s trusted chief air mechanic, Flegont Bassein, together with

co-mechanics Morozov and Petenin, crawled along the tunnel in the wing (see

opposite and diagram below) and tried to stop the flow. They came up with an

ingenious solution, by placing cloths over the leak, soaking up the outflow,

squeezing them out into a container, and pouring the liquid back into the

radiator. The engine kept going.

The mechanics did too, but barely. To reach the leak, they had had to

force an opening in the leading edge of the wing, radiators obviously being

exposed to the airflow. It was an act of fortitude that nearly cost them their

hands.

Well-Earned Fame

After the various great flights made by Soviet aircraft, the

pilots and crew were lavishly decorated, receiving many medals and testimonials

in the Soviet tradition. Moscow witnessed receptions that were as impressive,

if not quite so lavish, as those bestowed in New York on Lindbergh, Earhart, or

Hughes. And they were well earned. Mikhail Vodopyanov, for example, had built

up hundreds of hours of flying in remote parts of Russia, including the opening

of the Dobrolet route to Sakhalin. He had pioneered the route to Rudolf Island,

and had campaigned for aircraft landings on the North Polar ice, in opposition

to other views that the Papanin party should be dropped by parachute. His crew

members Mikhail Babushkin and Ivan Spirin had both flown big airplanes as early

as 1921, in the Il’ya Murometsy, no less. Vasily Molokov had been one of the

heroes of the Chelyuskin rescue, and his radio operator had been with him on

the long Siberian circuit. Anatoly Alexeyev had flown on a relief party to the

Severnaya Zemlya islands in 1934; while lIya Mazuruk and Pavel Golovin already

had outstanding records. When the Soviet Union decided to Go For The Pole, it

had the best cadre of trained and experienced pilots in the world to face the

daunting challenge.