The formation, organization, and operation of the U.S. Army

Parachute Test Platoon in June 1940 is a well-known story in the annals of

special purpose, special mission organizations. This was, however, the first of

two test platoons at the Army’s Parachute School at Fort Benning. The second

was activated on 30 December 1943 and originally contained 20 enlisted men and

6 officers, the majority transferring from the 92nd Infantry Division, then

stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. The unit designation for the second Test

Platoon was 555th Parachute Infantry Company. The 555th was the Army’s first

and only all-black airborne unit. During its major action in World War II,

Operation Firefly, the 555th (or “Triple Nickel”) would initiate and refine

special operations techniques still in use today.

On 18 February 1944, 16 of the 20 enlisted men completed

airborne training and received their coveted jump wings. Two weeks later, on 4

March, the six officers followed suit. These men formed the company cadre. As

new members of the company reported for training, the cadre rotated through

specialized training courses, such as jumpmaster, pathfinder, rigger,

demolitions, and communications. Many of the early noncommissioned officers

attended Infantry Officer Candidate School and, once commissioned, returned to

the 555th. When the company reached a strength of 7 officers and 119 enlisted

men, it shifted from individual to unit training. The progression of training

was typical for parachute units at the time, although in most other units

soldiers went through the training as individual fillers and not as a group or

unit.

Another significant difference in training that the 555th

initiated was in moving the men through leadership positions. On virtually

every training jump, a different tactical objective was included. Enlisted

soldiers were rotated behind the lines through as platoon and squad leaders as

well as on weapons crews. Bradley Biggs, a platoon leader of the 555th, wrote

later, “Over the period of these exercises each trooper had the opportunity to

lead and command, and to learn each assignment in a crew-served weapons team.

This leadership development made it possible for so many to be promoted.” On 17

July, the company transferred to Camp Mackall, where it was assigned to the

Army’s Airborne Command. The size of the company continued to grow. On 9

November, the company was redesignated Company A, 555th Parachute Infantry

Battalion, commanded by Captain James H. Porter. The battalion was authorized a

strength of 29 officers and 600 enlisted men. Everyone in a leadership position

moved up, squad leaders became platoon sergeants, platoon leaders and sergeants

became company commanders and first sergeants, and so on.

Two events, separated by almost three years, came to bear on

the history of the Triple Nickel. In Japan, the Doolittle raid on Tokyo and

other cities in the home islands in April 1942 shocked the Japanese. Until

then, they had believed the U.S. was not capable of invading the home islands.

They began to make plans to avenge the insult committed by Doolittle and his

raiders. They called this the “Fu Go weapons project.”

Meanwhile, in Europe, Hitler launched his last fateful

offensive, cutting through the American and British lines in the Ardennes Forest.

The 82d and 101 St Airborne divisions were badly chewed up by this battle and

needed many replacements. The 555th was alerted for duty in Europe but only as

a reinforced company with a strength of 8 officers and 160 enlisted men. This

downgrading action was necessary because the 555th was below its authorized

battalion strength and had not yet begun its battalion training. In April 1945,

just as the skeletonized company was completing almost three solid months of

training in the field and was ready to rotate to Europe, the German Army

collapsed. By this time, however, another threat had developed. Later that

month, the Triple Nickel was transferred to Pendleton, Oregon on a highly

classified mission, Operation Firefly. Having already made its mark in airborne

history, the 555th was about to stamp that mark in indelible ink. It would

accomplish this by fighting behind the lines in the U.S. northwest.

Beginning in November 1944, the Japanese had started their

campaign to make the United States pay for Doolittle’s raid. This campaign

consisted of sending balloons with incendiary bombs aloft so they would be

carried by the prevailing upper winds (what we now call the jet stream) to

America. Once over land the balloons would descend and drop their incendiary

clusters. The Japanese believed most of these incendiaries would land in large

West Coast cities and cause great havoc. In reality, most of those that made it

to the West Coast landed in uninhabited areas and became a serious problem for

the U.S. Forest Service, whose job included fighting forest fires in National

Parks and Forests.

The Forest Service had been created in 1905 by President

Theodore Roosevelt and had begun fighting fires almost immediately. By 1925 it

was using planes to spot fires and within four years was able to drop supplies

from planes to fire fighters on the ground. In 1940, the first parachute jump

was made on a forest fire. The following year, the U.S. Forest Service

Smokejumpers were organized.

When the balloon bombs were first discovered, military

intelligence offices noticed that the ballast bags contained sand. Samples of

this sand were delivered in secret to scientists of the U.S. Geological Survey

to see if it was possible for them to pinpoint either the balloon launch sites

or, at least, the origin of the sand. Four scientists, Clarence s. Ross, Julia

Gardner, Kenneth Lohmann, and Kathryn Lohmann, examined the sand. These

scientists were able, based on unique mineralogical and paleontological

assemblages, to confirm two likely sites on the east coast of Japan. Later

aerial reconnaissance corroborated the exact location of the second site and it

was subsequently bombed.

Working with the War Department, the Forest Service had been

able to prevent any widespread reports about the balloon bombs, although some

articles had appeared without attributing any cause to the fires. The Chief of

the Forest Service, Lyle F. Watts, was interviewed on radio in late May 1945,

describing the balloon bombs in some detail. What was not mentioned was the

fear that the balloon bombs would be used to carry chemical or biological

weapons. The presence of the Triple Nickel was also not mentioned.

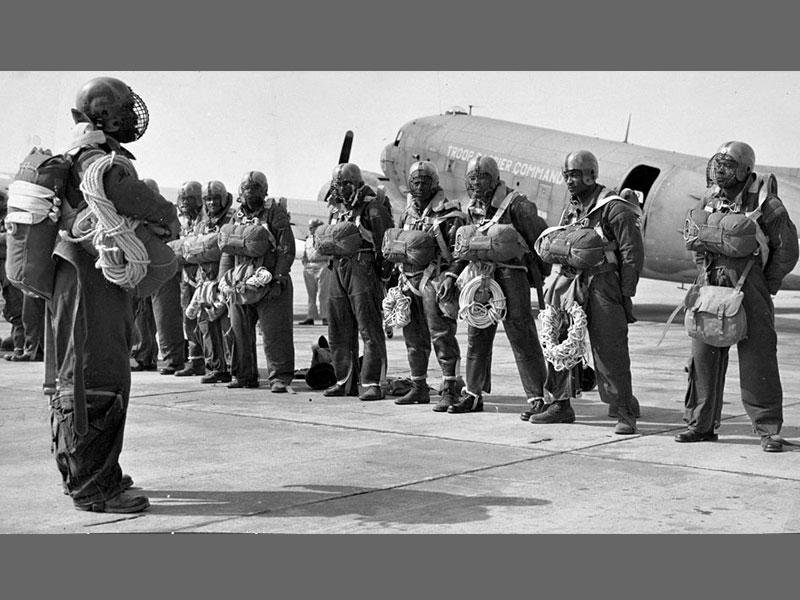

The 555th initially set up its main camp at an inactive B-29

Army Air Corps Base outside Pendleton, located in northeastern Oregon, and

immediately established a strenuous three-week training program for the

battalion’s soldiers with the Forest Service Smokejumpers. As the training

progressed the men of the Triple Nickel modified their uniforms to make them

more functional—and safer. A 50-foot length of nylon rope was added to assist

them down from trees, a common hazard in forest jumps. The heavy, fleecelined

jacket and trousers of the Army Air Corps bomber crews were added next to

provide padding for rough landings. Finally, they modified football helmets by

adding wire mesh grills to the front to protect their face and eyes. Once on

the ground, they donned gloves.

The major modification the paratroopers used was one

designed by Frank Derry, one of the very first Smokejumpers. Derry had cut

several panels out of the standard parachute and replaced one of the olive drab

suspension lines with one made of white material. By pulling on the white

shroud line, a jumper could turn in the air, to take advantage of the wind or

nullify it. It was thus easier to pick out a place to land instead of being

completely at the mercy of the wind. This is the first example of military use

of steerable parachutes.

Within six weeks the entire battalion had qualified as

Smokejumpers. During the training with their new chutes and modified clothing

and equipment, the men of the 555th also worked with explosive ordnance

disposal trainers to become familiar with disposal and disarming techniques. In

mid July, about one-third of the battalion moved to an Army Air Corps Base at

Chico, California. Splitting the unit provided wider coverage of forest area

(for both fire and balloon bomb response) and better use of the skills of the

paratroopers. Within a week of the move, each group had conducted its first

jump into a fire area.

Once on the ground after a jump, the Triple Nickel took off

the fleecelined uniforms and picked up whatever gear was needed, either to

fight a fire or work on a balloon bomb. Discarded uniforms, parachutes, and

unneeded equipment were left on the drop zone to be picked up on the way back

to camp.

One former member of the battalion described a fire

operation this way: “Digging a fire break or clearing a zone to either isolate

the fire or keep it from jumping is smoky business. We stank of smoke and

fought to keep upwind of it. Team work was the key. Watching out for your team

members, keeping together and not losing anyone in the smoke or darkness was

the top priority. We worked hard and ate like horses, often five big meals a day.

The forest rangers furnished most of our meals and water. We saved ours for

emergency or exit use.”

After a team arrived back at camp following a mission,

battalion officers and NCOs conducted detailed debriefings of each member and

filed afteraction reports. The average mission was four to six days long. On

several occasions the paratroopers jumped into Canada, trying to limit the fire

from spreading to the U.S. Captain Bradley Biggs stated that, in the case of

balloon bombs, “We blew up only those bombs that represented a danger.” Those

not blown in place were eventually turned over to an intelligence unit for

exploitation.

One of the most interesting missions the Triple Nickel

conducted during this period was to help train a group of U.S. Navy pilots who

were preparing to go overseas. Captain Biggs and 54 paratroopers from his

company were to jump before dawn onto a small drop zone and attack along a

15-mile route, calling in air support on a series of widely-separated targets

and then assaulting each target with live ammunition. It was a mission that

would task the hardiest paratrooper, lasting all day and with little room for

error. Biggs said that “It had all the features of a combat mission except for

a real enemy. There was the low altitude jump, full combat load, no ground

support, and no DZ markers or pathfinders.” For the Triple Nickel, it was yet

another chance to excel.

Biggs and his executive officer, Jesse J. Mayes, spent one

full day reviewing the plan and reconnoitering the route the men of the Triple

Nickel would cover. The drop zone was 400 yards long and 50 yards wide, and

located in the mountains. The route to the various targets was up and down hill

the entire way. There was great potential that heat and terrain could take a

heavy toll. Each man carried a double ammunition load, two canteens, medical

supplies, a compass, and two С-ration meals along with his combat pack. Jump

altitude was 800 feet, allowing little time to react to a problem or a

malfunctioning chute, “under conditions as close to combat as we might see.”

Each plane would make two passes, with nine paratroopers exiting per plane on

each pass.

The pre-dawn flight was very rough. Many of the paratroopers

became sick before they felt the planes slowing down and descending as they

neared the drop zone. Only one man was injured on the jump and had to be

evacuated. The remainder headed for their first target, which they had to reach

before the sun came up. They were in position and radioed the planes in as the

dawn broke. For the rest of the day, the operation went according to plan.

Just prior to the eighth and final target, the Navy dropped

a resupply of ammunition and water. This final target was within view of an

observation post where several senior Navy officers watched the demonstration.

Short of the target, the paratroopers laid out their two-feet by four-feet red

marker panels and called in an air strike with rockets and napalm. In the

follow-on ground attack, the men of the 555th fired off all their remaining

ammunition.

Before the paratroopers departed the exercise area the Navy

officers thanked them for their realistic support. “The commander of the naval

fighter squadron was extremely complimentary. A job well done.”

Between 14 July and 6 October, the Triple Nickel fought 36

fires (19 from Pendleton and 17 from Chico) and disarmed or destroyed an

unknown number of Japanese balloon bombs. In all, the missions included over

1,200 individual jumps with only 30 jump-related injuries and 1 fatality. They

conducted at least one demonstration jump, on 4 July in Pendleton. Operation

Firefly was an unqualified success. Because the Japanese balloon bomb operation

was classified, it was not until many years after the war that the real mission

for this operation was known and the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion could

receive full credit. The contributions the battalion made to special operations

rugged terrain jumping is obvious to anyone who conducts even a cursory review

of today’s techniques.

On 14 January 1946, by specific invitation of Major General

James M. Gavin, commander of the 82d Airborne Division and of the parade

ceremonies, the Triple Nickel took part in the World War II victory parade in

New York City. The 555th marched as part of the 82d and was authorized by Gavin

to wear unit decorations awarded to the “All-American” airborne division during

the war, including the Belgian forragère and the Netherlands lanyard. Just

prior to the parade, the 555th had been attached (not assigned) to the 82d for

admin and training purposes, physically locating back to Fort Bragg.

By September 1947, the 555th was assigned to the 82d and

redesignated as the 3rd Battalion, 505th Airborne Infantry Regiment, the

regiment Gavin commanded during the combat parachute assaults in Sicily and mainland

Italy in 1943. Gavin believed it was only right for his former unit to lead the

division in setting the example for integration.

On 9 December 1947, Gavin took the final step, a full 7½

months before President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, ordering “equality

of treatment and opportunity” for all members of the military forces,

irrespective of race, color, religion, or national origin. On that day, Gavin

signed an order integrating the 82d Airborne Division and moving the men of the

Triple Nickel to various units within the division and division headquarters.

Mission Critique

While planning Operation Firefly, the Army had no choice but

to conduct the mission, if for no other reason than to prevent panic in the

public at large. If the Japanese balloon bombs could be rendered harmless and

their existence kept quiet from the American and Canadian public, the operation

would be a success.

The U.S. planners had two choices for Operation Firefly.

They could use Forest Service Smokejumpers to do it or a military parachute

force. Using the Smokejumpers had at least two major problems: these civilian

firefighters would have to receive extensive explosive ordnance disposal

training and would, potentially, have to spend an unknown amount of time on the

mission, time when they would not be available for fighting forest fires. This

latter would require the Forest Service to hire additional people to take their

place on the fire lines.

Using military parachute infantry forces, who already had

training and experience in employing explosive ordnance was a more sensible

choice for Firefly. These paratroopers would require training in disarming

ordnance but their ramp up time would be a lot shorter than using Forest

Service personnel. Additionally, their cover as Smokejumpers was perfect for

their Firefly operations and was successful in preventing widespread knowledge

of the existence of the balloon bombs. As shown, they helped develop a jump

technique that is still used by special operations forces today, known as

rugged terrain jumping.

Although the main discussion stresses the Triple Nickel’s

contribution to rugged terrain operations there is another contribution that

this unit made. This one was not unique to the 555th; in fact, most of the

better special operations units in World War II made a similar contribution to

special operations doctrine. The 555th, however, did it better than anyone

else. This contribution is the method of cross-training unit members in a

variety of skills and in different leadership positions. This is one of the

best methods for building unit cohesion. Without this kind of cohesion the

members of the unit don’t work as well together, don’t reach the ultimate, at

least in special operations, of working as a team. The two best examples of the

team concept are the Alamo Scouts and the Triple Nickel; the SAS, Popski’s

Private Army, and the Jeds also demonstrate this quality well.

With this unit there are few examples from Vandenbroucke’s

criteria and most from McRaven’s. One of the criteria from Vandenbroucke’s

list, coordination, is present in several positive aspects here since the

Triple Nickel dealt with some interesting organizations, such as the U.S.

Forest Service and its Smokejumpers, and the U.S. Navy. Security, one of

McRaven’s key criteria, was the hallmark of Operation Firefly; it was kept so

secret that not until many years after the end of World War II was the role of

the 555th revealed to the public at large. This same security prevented the

Japanese from knowing how many of their balloons made it to North America,

where they landed, and what damage they had done.

All things considered, the Triple Nickel was typical of the

other special operations units in this study. They did the things that the best

special operations units did—they got good people, planned good operations, and

ехеcuted with skill and style. Both Vandenbroucke and McRaven would happily

give high marks to this unit and its operations.