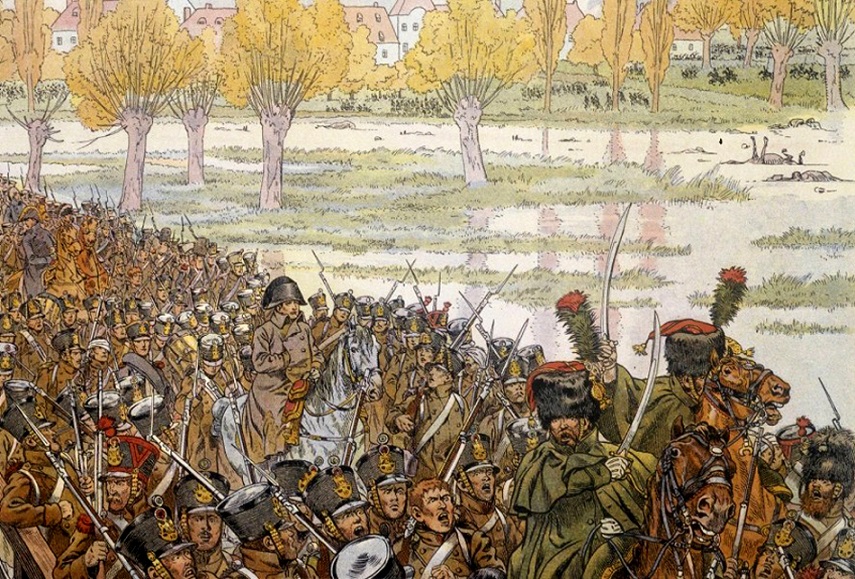

Napoleon’s retreat to the Rhine was on the whole a

remarkably successful operation. On the one hand the Allies were still

sufficiently daunted by the magic of the Emperor’s reputation to conduct their

pursuit of his columns respectfully, while Schwarzenberg was not a general of

sufficient caliber to trap the French before they could find sanctuary. For his

part, Napoleon was retiring along his main set of communications towards

Frankfurt and Mainz, absorbing the supplies and munitions of his depots on the

way. On October 23 some 100,000 French troops (many of them in ragged

condition, it is true, but by no means in a state of utter dissolution) reached

Erfurt, and much new equipment was issued from its huge arsenals before the

retreat was recommenced on the 24th. The discipline of some units began to

break down, and large numbers began to maraud, but apart from nuisance-raids by

bands of Cossacks, light cavalry and partisans, the retreat was not seriously

interrupted. However, Blücher’s army was marching westward on a parallel route

to the north, Schwarzenberg’s Austrians and Russians were pressing in upon the

rear, several sharp rear-guard actions had taken place over the previous week,

and so it behoved Napoleon to continue his retreat toward the Rhine.

As the days passed, there was an inevitable increase in the

disorganization of the Grande Armée. An Allied observer noted that “the numbers

of corpses and dead horses increased every day. Thousands of soldiers, sinking

from hunger and fatigue, remained behind, unable to reach a hospital. The woods

for several miles round were full of stragglers and worn out and sick soldiers.

Guns and wagons were found everywhere.”40

Nevertheless, there was a spark of fire still left in the

defeated army, as was convincingly demonstrated in the last days of October. A

force of 43,000 Bavarians and Austrians under General Wrede, newly committed to

the Allied cause, had rushed northward from the Danube into Franconia to block

the French line of retreat. In due course this force reached Hanau, a few miles

to the east of Frankfurt-on-Main, Napoleon’s next sanctuary. Through a complete

misappreciation of the situation, Wrede came to the conclusion that the Emperor

and the main body of his army were retiring along the more northerly road to

Coblenz, and that his force would only be faced by a dispirited flank column of

20,000 men at the most. Confident of success after several days of snappy

skirmishing, the Bavarian general placed his troops in hastily selected

positions on the 30th, with the River Kinzig behind his center and his right

wing in isolation to its south with only a single bridge linking it to the main

body.

Initially Napoleon had only the 17,000 men of Macdonald’s

infantry and Sébastiani’s cavalry available to deal with this obstruction, but

the French were able to advance to close contact virtually unseen owing to the

dense forests lying to the east of Wrede’s position. The Emperor soon decided

to attack the Bavarian left with all available manpower. By midday, the woods

facing the Bavarian center had been cleared by Victor and Macdonald, and

General Drouot soon thereafter found a track through the trees towards Wrede’s

left capable of taking cannon. Within three hours, Grenadiers of the Old Guard

had cleared the approaches to the French target, and Drouot assembled 50 guns

backed by Sébastiani and the Guard cavalry. A brisk cannonade soon silenced

Wrede’s 28 cannon, and then the French horsemen swept forward against Wrede’s

cavalry guarding his left. The Bavarians gave way before the onslaught.

Attacked in flank by the wheeling French cavalry, Wrede’s center was forced to

try and cut its way out to the left, skirting the banks of the Kinzig, and

suffered a heavy toll of casualties in the process. His right wing became

hopelessly involved trying to cross the single bridge, and proved incapable of

influencing the issue of the main battle. Hundreds were drowned in the Kinzig

before Wrede was able to rally the remnants of his forces on a line running

from the Lamboi bridge to the township of Hanau. The next day the French

occupied Hanau itself with scant difficulty.

Napoleon had no intention of wasting further time with

Wrede; as the main road to Frankfurt was now reopened, the bulk of the French

continued westward without delay, leaving a rear guard to prevent Wrede from

attempting anything further. The battle and the skirmishes that preceded and

followed it cost Wrede over 9,000 men. The French losses in action were

considerably lower, but between October 28 and 31 probably as many as 10,000

stragglers fell into Allied hands.

Nevertheless, the main body of the French army reached

Frankfurt on 2nd November. Here they were virtually safe, for their rear bases

at Mainz and the mighty barrier of the Rhine lay less than 20 miles away.

However, there is no possibility of minimizing the scale of the French

disaster. Although Davout was still firmly positioned on the Lower Elbe, the

French Campaign of 1813 had ended in complete failure. Perhaps 70,000

combatants and 40,000 stragglers reached the Rhine in safety, but almost

400,000 troops had been lost. It was true that no less than 100,000 of these

still remained scattered in isolated garrisons and detachments from Danzig to

Dresden, but there was no longer the least chance of their surviving or being

saved, and one by one these outposts began to capitulate. St. Cyr and the Dresden

garrison (two corps in strength), after conducting a gallant defense, were

induced to surrender on terms on November II. General Schwarzenberg

subsequently refused to ratify the agreement, but by then St. Cyr could do

nothing but surrender unconditionally. The Allies later played the same

disreputable trick against the garrisons of Danzig and Torgau. So the Campaign

of 1813 came to its close, with Napoleon and a remnant of his army preparing to

defend the natural frontiers of France, his Empire in Germany vanished forever.

What reasons underlay this new cataclysm? Here it is

possible to summarize only the main factors involved. We have already noted how

the quality of the French forces (both horse and foot) was markedly inferior in

quality to the armies of earlier years, but this was not in itself decisive.

Far more significant were the deficiencies of the French command system. These

were partly due to Napoleon’s shortcomings, and partly to the weaknesses of his

subordinates. In the period following the breakdown of the armistice, Napoleon

was trying to coordinate the control of half a million men—a task which was

simply beyond the powers of any one man with only the aid of the rudimentary

communications systems of the day, as the experiences of 1812 should have

taught him.

As a result—again as in 1812—the marshals inevitably found

themselves bearing greater responsibilities than they were used to on distant

sectors of the front. That they practically always muffed their opportunities

was partly due to Napoleon’s failure to train up his subordinates for the

exigencies of independent command, and partly to the rapidly dwindling

enthusiasm of the marshalate. To compensate his underlings for their complete

obedience and subservience the Emperor had showered them with riches, titles

and estates; by 1813, the recipients were not wholly unnaturally becoming

desirous of enjoying these benefits in a more peaceful setting. Many of the

disappointments of 1813 can be explained in these terms.

The rank and file of the extemporized French armies achieved

wonders on at least three occasions during the long campaign, but these

successes to some extent contributed to Napoleon’s undoing for he came

increasingly to rely on his “Marie-Louises” and decrepit veterans achieving the

impossible time after time. Many of the Emperor’s strategic plans were as

cunning as of old, but he lacked the means to implement them successfully—and

he was very slow in appreciating this. His raw troops could not march and fight

incessantly without adequate supplies, and his staff could not operate

efficiently without adequate intelligence. Even the Emperor’s funds of energy,

both physical and mental, were showing signs of exhaustion; his acceptance of

the armistice after two victories is probably one sign of this. Napoleon, in

fact, was relying on an unlikely combination of miracles and errors to achieve

his total victory; miracles of performance and endurance on the part of his

men—errors of judgment and coordination on the part of his foes. Neither lived

up to his most optimistic expectations.

The Allies certainly made mistakes, and several times as we

have seen these brought them to the brink of disaster. Their command system was

extremely chaotic and poorly coordinated. Selfish national interests often

replaced the common weal during their incessant councils; personal rivalries

and jealousies dogged almost every move. Nevertheless, after the sharp lessons

of Lützen and Bautzen in the first half of the campaign, they somehow hit upon

the correct strategy for bringing Napoleon to account By employing their vast

numbers of men and cannon against the secondary sectors of the French front and

by avoiding as far as was possible a direct head-on clash with “the Ogre”

himself, they disrupted plan after plan and severely shook the balance of

French operations as a whole. There were times (as at Dresden) when they

inadvisedly reverted to their old methods and suffered predictable defeat in

consequence, but once they had driven Napoleon and his tiring lieutenants back

on Leipzig and successfully linked up their four armies (those of Silesia,

Bohemia, the North and Poland), the game was practically in their pockets.

Napoleon fought with all his old tenacity, ferocity and skill, but in the end

sheer numbers told in the Allied favor.

Napoleon, indeed, was guilty of several severe political and

military miscalculations which between them underlay his failure. He tended to

despise his opponents; this was justifiable in the case of Bernadotte, but he

completely underestimated the degree of Blücher’s hatred for him or of the

Tsar’s persistence. He never expected that his father-in-law, the Emperor of

Austria, would turn fully against him; he never appreciated how sick were the

German States of the French yoke, or how unreal were his expectations of

military support from those quarters. He left thousands of invaluable fighting

men and several of his best generals south of the Pyrenees. But worst of all,

he never realized that there was a new spirit abroad in Europe; he still

believed he was dealing with the old feudal monarchies which in fact his

earlier victories had largely swept away. France was no longer the only country

to be imbued with a genuine national inspiration or equipped with a truly

national army. France’s foes had at last learned valuable lessons from their

earlier defeats, both political and military, and were now learning how to

employ their new-found strength against a rapidly tiring opponent. In the words

of General Fuller, for Napoleon the battle of Leipzig was “a second Trafalgar,

this time on land; his initiative was gone.”

Less than three weeks after the cataclysm of Leipzig, the

Emperor Napoleon was back at St. Cloud. With that astonishing resilience he

customarily displayed in time of catastrophe, he at once immersed himself in

planning the defense of French soil. For the second year running he had

witnessed the destruction of half a million French troops and the rapid

dwindling of his Empire’s frontiers, but still he appears to have believed that

his situation and prospects were not beyond hope. Given a little time to create

new armies, he was still confident of his ability to snatch a final victory

from his converging and seemingly all-powerful opponents. “At present we are

not ready for anything,” he confided to Marmont in mid-November, “but by the

first fortnight in January we shall be in a position to achieve a great deal.”

To anybody but a supreme egotist, France’s military

situation in the last months of 1813 must have appeared hopeless. Following

their victory at Leipzig, more than 300,000 Allied troops would soon be poised

along the Rhine, while the French could muster fewer than 80,000 exhausted and

disease-ridden survivors to defend the 300-mile length of their eastern

frontiers. Perhaps 100,000 French troops still remained in Germany and Poland,

but without exception they were divided into widely separated and closely

beleaguered detachments, incapable of taking any active part in France’s

impending death struggle. In North Italy, Viceroy Eugàne was narrowly holding

his own with 50,000 men along the Adige against the 75,000 Austrians of General

Bellegarde, but he already was finding good reason for concern about the

ambivalent attitude of Napoleon’s relation, the King of Naples. Amid the Pyrenees,

the armies of Marshals Soult and Suchet (sharing 100,000 men between them) were

steadily giving ground before the advance of Lord Wellington’s Anglo-Spanish

forces (125,000 strong). Napoleon could derive little satisfaction from a study

of the true situation on any of these fronts. He also faced the prospect of

open dissent in both Holland and Belgium. The French people were also fast

reaching exhaustion point after sustaining the ceaseless drain of its dwindling

manpower, year after year, and the economic repercussions of two decades of

warfare—gravely aggravated by the effects of the Royal Navy’s relentless

blockade of France’s ports—were steadily mounting. The Marshalate was war-weary

and increasingly mutinous; the dependable Berthier was seriously ill; and the

military resources of the German satellites were no longer available to eke out

the emaciated French war effort. All in all, Napoleon faced a chilling

prospect.

Still, however, the spirit burned; his will to success

remained indomitable. The Emperor goaded the jaded ministries of Paris into a

flurry of activity. New armies must immediately be created for the defense of

la patrie. Every last resource of manpower must be tapped. Edicts were issued

calling up no less than 936,000 youthful conscripts and aged reservists during

the winter months of 1813-14. Policemen, forest rangers, customs officers were

all summoned to the tricolor, together with 150,000 conscripts of the Class of

1815. Large parts of the National Guard were embodied for active service. Every

government controlled newspaper made emotional appeals for Frenchmen to rally

for the defense of their country as in 1792. Orders were sent to the armies in

Italy and Spain, calling for sizeable drafts of experienced soldiers to lead

the embryonic citizen armies. Decrees announced a vast expansion of the Young

Guard. New taxes would be levied to finance the war effort.

Simultaneously, Napoleon launched a full-scale diplomatic

offensive, planning to free his hands of peripheral problems. In the hope of

rallying Italian support behind Eugène, the Pope was released from house arrest

in France and restored to the throne of St. Peter. To clear the southwest

frontiers of France and make the veterans of Soult and Suchet available for

action on the Rhine, the French Government offered to restore Ferdinand to the

throne of Spain in return for a permanent cessation of hostilities—and a

preliminary agreement to this effect was actually initialed by French and

Spanish plenipotentiaries on December 11 at Valençay.

Napoleon was well aware, however, that the fruition of these

desperate policies could not take place overnight. There had to be a lull, a

breathing space, most particularly on the Rhine front where France was weakest

and her foes most imposingly strong. In optimistic moments, the Emperor spoke

of his hope that the Allies would delay their attack on France’s eastern

frontier until the spring of 1814. He based this assessment on three

considerations. First, the Allied armies must necessarily be in an exhausted

condition after their exertions throughout 1813. Second, it would take them

time to incorporate the forces of their new German allies and place their

communications in order. Third, Napoleon gambled greatly on internal

dissensions within the Alliance disrupting any plans for a winter offensive. By

the spring Napoleon was confident that France’s new armies would be, in

position along the Rhine, and he even dreamed, of a great offensive by Murat

and Eugàne sweeping from Italy over the Alps to threaten Vienna—a repetition of

1796-97.

To some extent Napoleon’s calculations concerning the

possibility of a stay in the Allied offensive were soundly based. Powerful

factions within the Allied high command were advocating just such a course of

action. The Emperor of Austria had at this time no great desire to see the

total eclipse of his son-in-law, for the downfall of the French Empire would

indubitably favor the interests of the Houses of Hohenzollern and Romanov

rather than those of the Hapsburgs. Providing Austria regained her Italian

possessions, Francis was prepared to grant France her “natural

frontiers”(namely the Rhine, Alps and Pyrenees) even at the cost of Belgium.

For purely selfish reasons, Crown Prince Bernadotte of Sweden was also opposed

to a full-scale invasion of France; he apparently harbored the hope that the

French people might be induced to replace Napoleon with himself, if affairs

were properly handled and excessive direct pressure avoided. The

representatives of Great Britain were equally concerned with the balance of

power in a post-war Europe, and tended to share Austria’s view that Napoleon

might be left the “natural frontiers”—less Antwerp and the Scheldt—providing

adequate guarantees of future good conduct could be extracted.

The advocates of immediate action placed their faith in the

Tsar. Alexander was actually of two minds on the subject. Desperately though he

wished to see Russian troops occupy Paris in revenge for Moscow, it

occasionally struck him that the soldiers of Holy Russia were being called to

make heroic efforts and sustain heavy losses for the benefit of the Germanic

powers rather than of Russia herself. On balance, however, he favored action.

As for Prussia, King Frederick William III was expected to follow the Tsar’s

lead, although personally he wished to avoid any unnecessary prolongation of

the war. Among the soldiers, opinion was equally divided. Prince

Schwarzenberg—“by nature a statesman and diplomatist rather than a

general”—tended to favor his master’s view, but the Prussian leaders, led most

vociferously by Blücher, demanded the immediate and vigorous continuation of

the campaign until the final overthrow of “the Corsican Ogre.”

In early November, their forces poised along the banks of

the Rhine, the Allied leaders went into conclave at Frankfurt-on-Main to settle

their policy. So serious were the divisions of expressed opinion that on the

16th it was decided to suspend operations for the immediate future while

Napoleon was approached with a conditional offer of the “natural frontiers.”

News of this development probably convinced Napoleon that he had won his pause,

however much he might distrust the ultimate motives of the Allies. To make the

most of his opportunity, he countered by calling for a general Congress, making

no definite mention of the proposed terms. As a sop to the Tsar, the Emperor

later appointed Caulaincourt as foreign minister and chief plenipotentiary. It

is dubious whether either side was completely genuine in its offers and

suggestions at this time. The Allies threw the validity of their pacific

postures into question when Napoleon provisionally agreed to the “natural

frontiers” suggestion, on November 30; his envoys were then informed that the

Allies had withdrawn their original offer, and it was eventually communicated

that talks could now only open on the basis of the “frontiers of 1792.” This

was out of the question for Napoleon. “I think it is doubtful whether the

Allies are in good faith,” he wrote to Caulaincourt in early January, “or that

England wants peace; for myself, I certainly desire it, but it must be solid

and honorable. France without its natural frontiers, without Ostend or Antwerp,

would no longer be able to take its place among the States of Europe.”

Some time before these lines were penned, the uneasy truce

along the eastern frontiers had been shattered. Napoleon’s hopes of a lull

extending into March or April were abruptly ended on December 22 when General

Wrede crossed the Rhine and laid siege to Hunigen. Even earlier, an Austrian

division under General Bubna had begun to occupy undefended Switzerland. By the

last days of the year it was clear that the Allied masses were on the move and

that der Schlag had come.

The main reasons that decided the Allies to open a major

winter campaign were distrust of Napoleon’s long-term intentions (probably

justified) and a wish to exploit the current atmosphere of unrest in the Low

Countries. Holland had already rebelled against French domination, and it was

felt that Belgium needed only positive action by the Allies to follow suit.

The plan was complex. The Army of the North was to split

into two. One corps under General Bülow, supported by a British expedition led

by General Graham, was to occupy Holland, advance on Antwerp and in due course

sweep through Belgium into northern France. The other half, commanded by Crown

Prince Bernadotte, Winzingerode and Bennigsen, was to isolate Marshal Davout’s

sizeable detachment around Hamburg, keep up pressure against the Danes and

continue the siege of Magdeburg. Covered by these secondary operations

Blücher’s 100,000 men of the Army of Silesia would advance on the central

reaches of the Rhine, secure crossings over a wide front between Coblenz and

Mannheim, and hold Napoleon’s attention. Simultaneously, Schwarzenberg

(accompanied by a veritable galaxy of Allied monarchs) would march from Basel

to Colmar, cross the Upper Rhine, and head for the Langres Plateau. Then the

second stage of the campaign would commence. While Blücher continued to pin

Napoleon frontally, the 200,000-strong Army of Bohemia would fall upon the

French right, subsidiary columns fanning out to the south and southwest to make

contact with the Austro-Italian forces advancing on Lyons and Wellington’s army

advancing from the Pyrenees. By mid-February at the latest, close on 400,000

Allied troops might well be operating on French soil, the majority of them

converging on the ultimate objective—Paris.