In the shimmering morning heat on 15 June 1941, the

slow-moving British Matilda “infantry” tanks were waved forward towards the

Halfaya Pass, which guarded the Libyan border from British attack. Soldiers of

the 11th Indian Brigade were walking behind the Matildas, confident the heavily

armoured tanks would provide protection from anything the Germans could throw

at them. The British Operation Battleaxe appeared to be going to plan.

Waiting for the 11th Indian Brigade and Matildas were 13

88mm flak guns dug into undulating desert terrain and camouflaged with netting.

When the first Matildas hit a hidden minefield and started to have their tracks

blown off, the time was ripe for the German gunners to open fire. One squadron

of the 5th Royal Tank Regiment was destroyed in the first salvo and the rest of

the regiment was soon in retreat. Further attacks by the British 4th Armoured

Brigade fared little better. The Matilda’s 2-pounder cannons did not have the

range to reach the German guns, which were easily picking targets off at more

than 1500m (1640yd) range. Even if they could have closed on the German

position, the British tanks lacked high-explosive shells because their primary

task was to deal with enemy anti-tank gunners by using their machine guns.

In the space of four days the British lost 123 out of 238 of

their tanks and failed to budge the Germans from Halfaya Pass. The battle

forever destroyed the Matilda’s reputation for invulnerability, and soon Allied

tank crews came to fear the weapon they called the “Eighty-Eight”. To their

German crews, they were nicknamed the “Acht-Acht” and their presence on the

battlefield was a great morale booster. Not only did they keep Allied aircraft

at bay, but it was very reassuring for German soldiers to know that they were

protected by a weapon that could also defeat any Allied tank. For a gun that

was supposed to be an anti-aircraft weapon, the fact that the “Eighty-Eight”

should achieve fame as an anti-tank gun was no surprise to its designers.

Under the terms of the 1919 Versailles Treaty that ended

World War I, Germany was denied the right to possess anti-aircraft artillery.

The army of the new Weimar Republic, the Reichswehr, was not going to let such

legal niceties get in the way of its plans to develop new weapons. It started

to fund the famous armaments firm, Krupp, to set up a secret research base in

Sweden in cooperation with the Bofors company. In return, Bofors was invited to

set up a branch office in Berlin that was manned solely by Germans. Throughout

the 1920s the German designers worked away, preparing for the day when they

could openly return to business as usual. Krupp and Rheinmetall were asked

towards the end of the decade to design a new anti-aircraft gun, but it was not

until 1931 that a satisfactory product was ready. This experimental 88mm gun

featured many of the characteristics of the weapon that would be famous in

World War II: it had a cruciform wheeled carriage and an 85-degree elevation to

fire at aircraft. To fire, the cruciform carriage was lowered to the ground and

two elevating side legs dropped to form a firm base. The gun also had a

360-degree rapid traverse. After the rise of Hitler in 1933, Germany reneged on

the Versailles armaments restrictions and Krupp was ordered to begin production

of its weapon, designated the 88mm Flak 18.

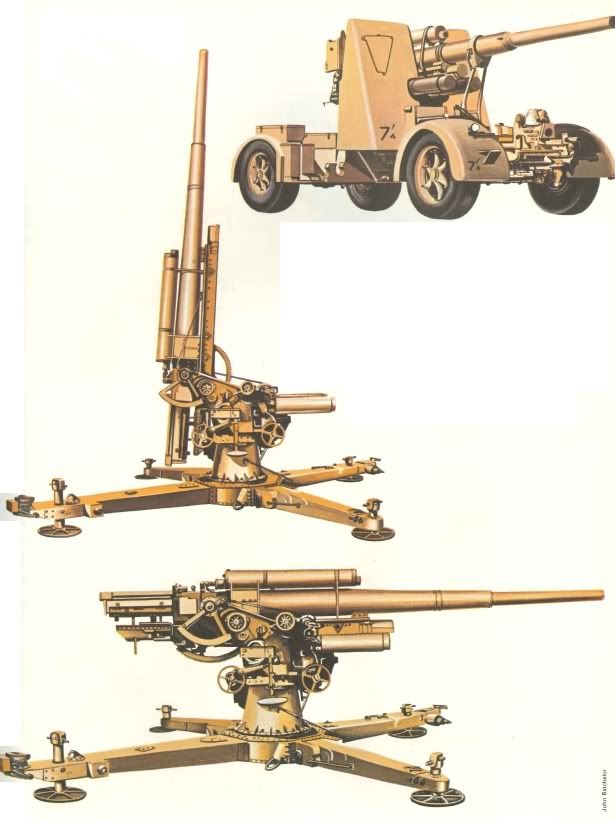

The Flak 18

The Flak 18 was a hardy design. It was transported on the

Sonderanhänger 201 limbers (two two-wheeled sets), and when deployed for firing

stood on a cruciform platform comprised of four legs horizontal legs meeting at

the central gun pedestal. This design gave the gun a 720-degree traverse;

elevation was from minus 3 degrees up to 85 degrees. The gun itself had a

single barrel held within a jacket, and also a novel “semi-automatic” breech

system that automatically ejected spent shell cases. This latter features,

along with the unitary cartridge design of the 88mm’s shells, meant that over

15 rounds a minute could be fired by an experienced crew in action – heavy

firepower indeed.

The Flak 18 fired armour-piercing or high-explosive shells

at a muzzle velocity of 820mps (2690fps) to a maximum ceiling of 9900m

(32482ft). However, it didn’t take long for artillery officers to realise that

tha gun could also perform well in an anti-tank role, with a maximum ground

range of 14.8km (9.25 miles). Operational experience in the Spanish Civil War

(1936–39) bore this out, and the Flak 18 began its career as an anti-tank

weapon.

Improvements were soon made to the Flak 18 and its carriage,

resulting in the Sonderanhänger 202. This received identical front and rear

limber sections, each axle having four tyres set in double-wheel arrangements.

A barrel support was added to each end of the limber (the Sonderanhänger 201

had only one barrel support) so the gun could be towed facing either direction.

Performance was unchanged, but a new three-section barrel was designed. This

allowed worn out parts of the barrel to be replaced, rather than the entire

barrel itself, hence saving time and materials (rear rifled sections tended to

wear out more quickly than muzzles, for example). This design modification also

made it possible for units to replace barrels in the field; Flak 18s had to be

shipped back to workshops behind the lines to have their heavy one-piece

barrels replaced. There were various other changes affecting the sighting

systems and other parts of the gun. The new gun and its mount was called the

Flak 36. However, it should be noted that Flak 18 barrels often ended up on

Flak 36 guns and vice-versa.

It was not long before further refinements were introduced

to produce the Flak 37. The changes were mainly concentrated on the

fire-control system, and allowed the gunlayer to more easily follow

instructions supplied to him from a battery fire direction post. The barrel

liner was also replaced with a two-piece unit, rather than the Flak 36’s

three-piece barrel.

The Flak 18, 36 and 37 were the bulk of the 88mm gun

variants deployed by the Wehrmacht in World War II, though there were a number

of attempts to improve on this tried and tested design. Rheinmetall, the

designers of the original Flak 18, developed the Flak 41; a version with a

longer, five-part barrel. A few hundred were built, but technical problems and

production delays meant they never replaced the older models in widespread use.

It is thought that few, if any, Flak 41s were ever deployed outside of Germany.

The Krupp design bureau also attempted to improve on Rheinmetall’s original

design in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Krupp’s engineers drifted from their

original brief and ended up effectively redesigning the entire weapon from

scratch, though their final product – called the 8.8cm Gërat – was by most

practical criteria identical to the Flak 37.

The success of the 88mm in the anti-tank role in North

Africa and Russia, and the appearance of heavily armoured Soviet T-34s and

KV-1s, made the Weapons Office look to producing a specialist anti-tank version.

This was a pressing requirement because the existing 50mm and 75mm anti-tank

guns were unable to deal with the new Soviet tanks. An important requirement

was to reduce the silhouette of the weapon to make it easier for their crews to

camouflage and conceal them. Krupp modified their design for the 8.8cm Gërat,

adapting it for a purely anti-armour role and reducing the size of its recoil

mechanism. The result was the PaK-43, which retained the cruciform carriage of

the old 88mm, though this was soon superseded by the PaK-43/41 which was

mounted on a single axis carriage, like a traditional artillery piece. While

crews liked the killing power of the new anti-tank gun, they were less

impressed by its size and weight – more than 6 tonnes (5.9 tons) – and soon

nicknamed it the “barn door”.

The basic 88mm Flak 18 weapon weighed 7.1 tonnes (7 tons),

which meant it was not easily manhandled once the crew had lowered it from its

wheels. Just as famous as the weapon itself was its Kraus-Maffei SdKfz 7

halftrack prime mover, which could carry the gun’s crew and a basic load of

ammunition.

Operating the weapon was a very labour-intensive process. A

single gun was served by a crew of nine, which included a commander, layer to

elevate the gun, layer to traverse the gun, a loader, four ammunition handlers,

two fuse setters and a tractor driver.

Some of the first guns were sent to Spain with the German

Condor Legion to protect the airfields used by General Franco’s fascist forces.

When they ended up being used against ground targets, the Luftwaffe High

Command realized that it needed to order armour-piercing rounds for the weapon

and armoured shields to protect their crews from shell fire. These improvements

were in hand when war broke out in 1939.

The weapon’s high velocity – 820m (2690ft) per second – was

the key to its success in both the anti-aircraft and anti-tank roles when

supplied with the correct ammunition. For anti-aircraft work, it was provided

with time- and pressure-fused high-explosive shells to allow the crew to set

the altitude at which the shells exploded. In the ground role, three main types

of round were available. The Pzgr 39 armour-piercing, capped, ballistic cap

(APCBC) round was the first round used and was later supplemented by the Gr

38HI high-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) round, and Pzgr 40 armoured-piercing,

composite rigid round, which had a tungsten core. With this ammunition an

“Acht-Acht” could punch through 99mm (3.8in) of armour at 2011m (2200yd), which

meant no type of Allied tank was safe until the arrival of the Soviet Josef

Stalin tank in early 1944. Poorly armoured tanks, such as the Sherman and T-34,

which had only 51mm (2in) and 47mm (1.8in) frontal armour respectively, were

easy prey for the 88mm at ranges in excess of 3000m (3282yd).

Although a large number of “Flieger-Abwehr-Kanone” or flak

units had been formed in World War I, Germany was banned from possessing air

defence artillery by the Versailles Treaty. In secret the Reichswehr reformed

its flak units in 1928, and disguised them as transport detachments and

elements of the German Air Sports Union. Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 was

quickly followed by the establishment of the German Air Ministry, which was a

cover for the secret formation of the Luftwaffe. Responsibility for flak units

was soon passed from the army to the Luftwaffe, because of the need to

integrate anti-aircraft artillery with fighter defences. In only four years the

flak branch was expanded to some 115 units, which had the job of defending

airfields, key strategic locations and the field army. Two years into the war

this number had expanded to 841 units. The flak artillery were divided into

static units committed to the defence of the Reich and self-propelled units

that accompanied the army into battle. The battalions of self-propelled flak

artillery were the elite of the branch and were in the thick of the action

throughout the war.

The Army High Command had never been happy with the

Luftwaffe having total control of the flak branch, and in 1941 both the Army

and Waffen-SS were allowed to form their own flak battalions to be assigned to

infantry, panzer, motorized and panzergrenadier divisions. These units had a

mixture of 88mm and 20mm or 37mm light flak weapons to protect their divisions

from enemy aircraft. However, all matters relating to flak weapons, ammunition

and equipment, as well as tactics, doctrine, training and organization, still

remained the responsibility of the Luftwaffe flak branch.

While fighter pilots and paratroopers received public

adulation as the Luftwaffe’s war heroes, the flak gunners were elite non-flying

units of the German air force. Operating weapons, such as the “Acht-Acht”, in

the anti-aircraft role, was very demanding because crews had to be able to

understand the complex fire solutions needed to set fuses to explode at high

altitude. They also had to work as part of a complex air defence organization

so friendly aircraft were not mistakenly engaged. The firing crews had to be

fit and determined, firstly, to manhandle their guns into position, dig firing

pits and maintain the supply of shells to the gun. Each shell weighed in at

more 9kg (20lb) so this was no mean feat.

Gun and battery commanders were highly trained to get the

most out of their weapons in the anti-tank role. Once committed to battle the

“Acht-Acht” were virtually immobile, so the difference between success or

failure depended on the siting of the guns and their concealment until the time

came to engage the enemy. Once battle was joined with enemy tanks, flak

commanders required strong nerves and faith in the capabilities of the guns and

their crews. Outside the cockpit of a fighter or combat as a paratrooper, being

a flak gun commander was the quickest way in the Luftwaffe to die for the

Führer.

In the first two years of the war, Luftwaffe fighters ruled

the skies over Europe’s battlefields, relegating flak gunners to relatively

straightforward point defence tasks. The brunt of these tasks fell to

divisional or corps flak battalions or regiments, which travelled close behind

the panzer spearheads. During the Blitzkrieg in France, the Balkans and Russia,

divisional “Acht-Acht” batteries were often called upon to engage pockets of enemy

tanks that could not be dealt with by the panzer regiment. These were

small-scale engagements, involving one or two flak guns being called upon to

knock out handfuls of British, French or Soviet heavy tanks that had broken

through the German front.

Massed Flak Batteries

As the Allies and Soviets started to boost their airpower

and challenge the Luftwaffe, the Germans began to take air defence more

seriously and major resources were put into building up flak batteries. Soviet

offensives in the winter of 1942–43 also saw the massed employment of hundreds

of T-34s along narrow fronts. In response, the Germans saw the need to field

anti-tank defences capable of countering this threat. Massed flak guns were one

answer to the growing tank and air threat. Rommel showed what was possible with

his use of massed 88mm batteries in the North African desert, and the Germans

looked to repeat this success in Russia.

By the summer of 1942, the bulk of 88mm guns in frontline

areas had been concentrated in 10 Luftwaffe motorized flak divisions, which

were raised to provide air defence for army groups. The divisional flak

commander was responsible for the organization of all air defence activity –

flak guns, radars, searchlights and fighters – in the army group area. A flak

division possessed awesome firepower, usually between 12 to 30 heavy flak

batteries, each of four 88mm guns, and a similar number of medium and light

batteries, each with a dozen quad 20mm or 37mm cannons.

He, in turn, posted his motorized flak regiments and

battalions to key sectors of the front to support a particular army or corps.

In times of crisis, they could be concentrated to provide either blanket

protection against enemy air forces or a powerful anti-tank emergency reserve

against an armoured breakthrough. If necessary, they could also supplement army

artillery battalions in general fire support tasks. Unlike the majority of army

artillery units, which were still horse-drawn, the Luftwaffe generously ensured

all its flak battalions were fully motorized. With a typical motorized flak

regiment mustering more than 20 “Eighty-Eights”, in effect they were a highly

mobile tank-killing force, available to rapidly concentrate firepower at a

crucial point on the battlefield if the going got really desperate.

Flak regiments were not committed to the emergency anti-tank

role without prior planning and reconnaissance. As a standard procedure, flak

commanders would survey their sector of the front for possible firing positions

in case enemy tanks broke through. Guns were to be sited to make maximum use of

their long range, so clear fields of fire were a must. Overlapping fields of

fire were also allocated to individual guns and batteries, so the whole of the

front could be swept by fire, creating killing zones. The high silhouette of

the 88mm flak gun meant weapons had either to be dug into pits, or hidden in

woods and buildings to prevent them being spotted. Good concealment was

essential to stop the attackers spotting the flak guns until they were well

inside the kill zone and unable to escape. If the enemy spotted the flak guns

too soon, then their artillery would fire on the flak batteries with deadly

effect.

The pre-positioning of anti-tank ammunition near to the gun

line was very important to ensure that a rapid rate of fire could be maintained

for as long as necessary. Flak commanders also liked to have friendly infantry

close at hand to protect their guns from enemy ground troops, who might try to

infiltrate and destroy them.

Flak commanders identified key points to be defended and

concentrated their guns there, to ensure that the defence line held whatever

happened. They had to juggle their mission to provide air defence, with the

need to counter breakthroughs of enemy armour. Often the requirements of both

missions overlapped: for example, defending strategic bridges, railway lines or

high ground. Movement to other key sectors on the battlefield was regularly

rehearsed so flak units could rapidly move on receiving an accepted codeword.

In emergency situations, a flak commander was usually the

first officer on the scene with battle-winning equipment, so they assumed

command of the action against the rampaging enemy tanks. Any infantry or troops

on the scene subordinated themselves to the flak commander as part of ad hoc

battlegroups. No matter how much forward planning had occurred, this was when

the flak commander got to show his mettle. They often had to bring order to a

chaotic situation, ensuring their guns were in position and fire discipline was

maintained until the vital moment. This was a time for iron nerves.

The Battle of the

Meuse

The first decisive intervention by “Acht-Acht” guns occurred

in May 1940. Heinz Guderian’s panzer corps raced to the River Meuse at Sedan to

build the bridgehead needed to open a breach in French lines, allowing the

panzers to race to the English Channel. Guderian, the father of the German

panzers, had the Luftwaffe’s Flak Regiment 102 attached for this operation, and

gave it a key mission. Colonel von Hippel’s regiment had been specially

reinforced and trained for its part in an operation that was to turn the battle

for France in Germany’s favour.

Once the panzers had reached the river, infantry were

ordered across in rubber assault boats to seize a bridgehead. French troops and

guns emplaced in concrete bunkers high on the far bank were turning the German

assembly areas into killing zones. Guderian had already thought about dealing

with the French defences, and he had sent his flak gunners to Poland to

practice putting shells directly through the firing ports of abandoned Polish

bunkers. Covered by panzers, the 88mm crews rolled their guns up to firing

positions on the river bank opposite the bridgehead, and started to pick off

the French bunkers. In some places the flak gunners were less than 100m (109yd)

from their targets, and the 88mm proved to be superbly accurate.

This impressive display of firepower was just the morale

boost the assault troops needed as they dropped their boats in the Meuse on 13

May. By the end of the afternoon Guderian had his bridgehead, and during the

night the engineers had built the first of several pontoon bridges. The flak

gunners moved two 88mms across the river just behind the first panzers and they

were soon in action, knocking out French tanks sent to counterattack during the

night.

When morning broke, the French and British realized the

danger posed by the German bridgehead. Within hours, hundreds of bombers were

on their way to put it out of action. Colonel von Hippel’s gunners were the

only defence available to protect the key bridges. Luftwaffe fighters took on

the covering RAF Spitfires, but the bombers pressed home their attacks on the

bridges with fanatical bravery. The flak gunners elevated their 88mms and

started to pick them off. Wave after wave of bombers were met by a wall of

exploding shells. The aircraft that were not hit were forced to abort their

bomb runs. By the end of the day, Guderian’s bridges were still intact and 112

Allied bombers had been shot from the sky. The panzer general commented that,

“our anti-aircraft gunners proved themselves on this day, and shot superbly.” A

grateful Führer awarded von Hippel with the Knight’s Cross.

Erwin Rommel already had experience of using his 88mm flak

batteries as an emergency anti-tank force during the Battle of Arras in June

1940, knocking out eight Matildas. At Sidi Rezegh in November 1941, Rommel’s

flak front stopped the British 7th Armoured Brigade in its tracks, after its

commander had rashly ordered his tanks to charge headlong across the desert

directly at the Germans. Only four 88mm guns were dug-in on the first day of

the battle and they devastated the British brigade. For reasons best known to

the British brigadier, he repeated the exercise over four successive days and

some 300 British tanks were left destroyed by the “Acht-Acht” and a group of

50mm anti-tank guns sent to reinforce the flak battery.

Gun crews had to be ready for action at a moment’s notice,

against unexpected threats. During the battle for the Gazala Line in June 1942

Rommel used his flak guns aggressively, placing batteries close behind the head

of his panzer columns. If British tanks were encountered the panzers were to

fall back and leave the “Acht-Acht” to deal with them at long range. On the

opening day of the battle, the 21st Panzer Division found itself up against 40

of the new American-supplied Grant tanks for the first time. With their 75mm

cannon, the Grants out-ranged the German Panzer IIIs and so the latter began a

hasty withdrawal away from the new threat. Rommel was close at hand to direct

Colonel Wolz’s 135th Flak Regiment to steady the German line. Four 88mm guns

were quickly formed into an improvised gun line to protect the Afrika Korps’

supply trucks. As the Grants got to within 1500m (1640yd), the 88s roared into

life. The British tanks started “brewing up”, forcing the rest to pull back.

Rommel’s aggressive use of the 88mm in North Africa established its reputation

as a “bogey weapon” in the eyes of British tank crews.

On the Russian Front, German flak units increasingly took on

more anti-tank duties as the weight of Soviet offensives increased. The summer

of 1943 saw a rejuvenated Soviet armoured force take the offensive after the

German Kursk Offensive had been checked. Pre-positioned Soviet tank reserves

were unleashed just as the German panzer spearheads had been worn down by

anti-tank defences and minefields. With great skill, the Soviet High Command

struck at the weak flanks of the German front and, within days, it had been

shattered in several places north of Orel. Four Soviet tanks corps smashed

through the German Second Panzer Army’s front and raced towards the key rail

junction at Khotynets. Luftwaffe tank-busting planes and 88mm guns of the 12th

Flak Division were the only things that could stop the hundreds of tanks

surging southwards. Unless the rail junction was held, panzer reserves would be

unable to reach the crisis zone.

Flak Against T-34s

Although the German fighter-bombers were able to shoot up an

entire Soviet tank brigade, more T-34s continued the offensive. A battalion of

88mm guns, already on the move under the cover of darkness, was able to set up

a gun line outside Khotynets. When the Soviets tried to stage a coup de main

raid on the town they drove into a firestorm of 88mm shells and fell back. More

attacks continued over a three-day period, but more “Acht-Acht” batteries

arrived to bolster the German defence. Casualties were heavy among the flak

gunners, who had to fight off the Soviets virtually unsupported by artillery or

armour.

During this desperate battle the division claimed 229 tanks

knocked out and ensured the safe arrival of panzer reinforcements, allowing the

breaches in the front to be restored. The success of the 12th Flak Division

validated the mass employment of the “Acht-Acht” as emergency anti-tank forces.

The next major test of the 88mm came in the summer 1944 on

the Normandy Front. In late July the British massed almost 800 tanks around the

city of Caen to punch a hole through I SS Panzer Corps’ front. A mix of Army,

Waffen-SS and Luftwaffe 88mm flak and anti-tank battalions, with some 78 guns,

were concentrated in this key sector. In spite of being on the receiving end of

saturation bombing by 1000 Allied heavy bombers, the German defences were ready

when the first wave of British tanks kicked off Operation Goodwood early on 18

July. The British 11th Armoured Division was sent forward through a 4.8km

(3-mile) wide bridgehead. Backed by Tiger and Panther tanks of the Waffen-SS

Leibstandarte Panzer Division, the surviving “Acht-Acht” gunners emerged from

the ruins and started firing into the huge column of British Shermans. By the

end of the day more than 300 British tanks were burning in front of the German

lines, many of which fell to 88mm flak and PaK-43/41 guns. A renewed attack the

following day only resulted in 100 more British tanks being destroyed.