In 1939, however, colder economic winds began to blow. Greek Dictator Ioannis Metaxas poured every available drachma into building up Greece’s industry and military establishment, and as a result, the country’s borrowing bill soared. Between 1936 and 1940 some fifteen billion drachmas had gone into rearmament. Greece was sinking into a sea of red ink. Whereas in 1935 Greece’s public deficit stood at 373 million drachmas, by 1937 it had yawned to 1.7 billion drachmas, dipping to 341 million in 1938 and climbing back up to 1.5 billion in 1939. In April 1939 the Greek government was paying out up to forty per cent on Greek state bonds, with jittery London lenders demanding sixty-five per cent. Britain’s credit institutions were fretting over Greek orders for warplanes and other military materiel, fearing that a European war might erupt before they could get their money back. Greece already had a shaky record of defaults going back to the 1840s. Greece’s neighbours to the north, meanwhile, were changing their stance in the face of the growing German menace. Bulgaria let its arms-limitation agreement with Greece lapse, while Italy delivered a nasty surprise by occupying Albania on Easter Monday 1939. In the circumstances Metaxas felt he had no choice but to accept an informal guarantee of Greece’s territorial integrity by Britain and France. Somehow, the London City lenders were fobbed off, but grumbling continued.

To aid national rearmament Metaxas promoted a domestic steel

industry, though against the opposition of Britain and Germany which feared the

loss of a market for their own steel. Some industries had to be bullied into

building up national power.

The War Ministry made itself unpopular, for example, when it

ordered the textiles industry to come up with nearly three million metres of

khaki fabric for military uniforms at a price set by fiat. The dissident voices

were silenced when the chairman of the League of Greek Industry (SEBB), Andreas

Hadjikyriakos, was co-opted into Metaxas’ administration as national economy

minister. Hadjikyriakos’ ministerial career was short-lived. In May 1937 the

SEBB board unanimously decided to launch a nationwide collection for the

purchase of modern warplanes for the six-year-old fledgling Royal Hellenic Air

Force. When the collection came up with forty million drachmas in short order,

Metaxas was delighted. But his joy soon turned to fury when a financial

newspaper published a list of contributions by captains of industry against

their recorded profits, showing that those men enjoying the highest profits had

contributed the least. To keep Greece’s infant war industry afloat, Metaxas

passed a new law in January 1938 allowing the seizure of industrial property

assets.

Though the economics were worsening, Metaxas could not

afford to slow down his war preparations. Major items such as aircraft,

warships, artillery pieces, machine guns and rifles had to be purchased abroad.

Britain, Germany, France, the United States and even Poland and Yugoslavia were

approached, as part of the prime minister’s plan not to be too dependent on a

single power. Britain was the favoured supplier of the big-ticket weapons such

as ships and aircraft, as the Royal Hellenic Navy had been organized by the

British, who also were influential in the RHAF. The French, who had organized

the Greek army, had a near-monopoly on arms supplies and munitions for land

warfare. The RHAF, the young newcomer to the services, had to make do with a

truly mixed bag of warplanes from four countries, complicating the supply and

technical processes. Three days before Metaxas’ parliamentary coup, Lieutenant

General Papagos, a staunch royalist, had been appointed to the post of Chief of

the Greek Army Staff. Once in his job he reorganized and streamlined the staff

to include quartermaster, transport and industrial warfare sections. His calls

for military credits to meet these new requirements, however, were not always

heeded by the Defence Ministry.

When the Second World War broke out on 1 September 1939

Greece was quick to proclaim its neutrality. But few had the illusion that the

country could stay uninvolved for long. When France fell in May 1940 Metaxas

ordered some reservists called up, a move which rattled Italy. As early as 18

January the Italian daily Corriere della Sera was spouting the official Rome

propaganda line that Greece was preparing for a mountain war in Albania ‘with

such obviously offensive tactical plans’. Metaxas’ vehement protestations of

neutrality were ignored. Crews of the Italian airline Ala Littoria were

instructed to spy on the Greek island ports they overflew and the Greek

aerodromes they used. Metaxas was becoming increasingly troubled. ‘Will

everything collapse?’ he mused in his diary in June. ‘If so, I’ll go with the

army and seek to be killed.’

By September 1940 Athens could have no doubt about what was

looming. Security in Rome was not of the best, not to mention Mussolini’s lack

of discretion in his public utterances. In Athens Emanuele Grazzi, the Italian

ambassador, and Colonel Luigi Mondini, his military attaché, were sending home

long and urgent cables detailing the efficient mobilization measures of the

Greeks; reservists, they fretted, were being called up by the thousands. For a

long time Greek defence planners had been divided as to whether Bulgaria or

Italy was the greater threat. After the sinking of the Elli, however, all

ambiguity had vanished. The gradual build-up of Italian forces in Albania had

pushed concerns over Bulgaria to the sidelines.

One prescient officer who had foreseen that, if an attack on

Greece were to come, it would come from the direction of Albania, was General

Haralambos Katsimitros, the commander of the 8th Division based in the

north-western city of Ioannina. Since taking up his command in 1938 Katsimitros

had devoted his energies, despite a chronic shortage of military credits, to

beefing up defences in Epiros, the northwest corner of Greece abutting Albania.

Defying disapproval by his boss Papagos, he dotted the craggy countryside with

tank traps and caves in which to hide artillery. Some of these preparations

spooked commentators in Rome. On 18 January 1940 the Italian daily Corriere

della Sera had asked in an editorial ‘how come those Greeks are equipped for a

mountain war with such obviously offensive plans?’ Within ten months the 8th Division

had built up its full strength to ten infantry battalions (three of which were

made up of called-up reservists), joined by the 9th Division with six

battalions of infantry and a reduced-strength 1st Division held in reserve,

accompanied by artillery.

There was more where that came from. Greece could field a

total of five army corps consisting of fifteen infantry divisions and one

cavalry division, fifteen regiments of mountain artillery and five of field

artillery, plus scattered anti-aircraft units. The bulk of Greece’s rearmament,

in fact, had overwhelmingly benefited the Army, with the underequipped Royal

Hellenic Navy (all of ten destroyers, thirteen torpedo boats and six

submarines, a handful of minesweepers and the ancient hulk of an armoured cruiser

as a reserve) and the flimsy Royal Hellenic Air Force (barely 130 front-line

aircraft) left to manage as best as they could.

When Visconti Prasca ordered his legions to cross the Greek

border at 5.30 am, 28 October 1940, he found his first unexpected foe in the

weather. Autumn in the Balkans can be a riot of gold and ochre-coloured forests

wreathing the sunlit mountains. But for two days the rain had come down in

torrents, turning the dusty mountain tracks into brown quagmires sucking down

boot and hoof. Ordinarily gentle mountain gullies became raging cataracts. Men

and horses and mules struggled through the mire. But Visconti Prasca was

unperturbed; bad weather, he figured, would be bad for the enemy as well. What

he apparently failed to realize was that though mud and rain indeed affected

all alike, they were immeasurably harder on an advancing army than on one in a

defensive position.

Rossi’s Twenty-fifth Corps, dubbed the ‘Chamuria,’ advanced

in the centre, while in the west, hugging the grey and choppy Ionian Sea, a

regiment of the Raggruppamento del Litorale under Colonel Enrico Andreini

pushed through sheets of rain into Greek territory, while to the east the first

two regiments of the Siena Division, Colonel Carloni’s 31 Infantry and Colonel

Roberto Gianani’s 32 Infantry crossed the frontier. On their left the Ferrara

also advanced, with the 47 Infantry (Colonel Trizio) and the 48 (Colonel

Sapienza) in the lead. Trundling towards the Kalamas River valley were a

regiment of Centauro Division armour and feather-hatted bersaglieri under

Colonel Solinas. None of these units at first encountered any resistance, as

Papagos’ Plan IB had provided for an initial strategic withdrawal to more

defensible positions along the Kalamas River. Greek border and customs posts

stood abandoned. Italian soldiers noted plates of half-eaten food on the tables

and portraits of Metaxas and King George still on the walls. Behind the advance

units of the Ferrara lumbered the rest of the Centauro’s light tanks, their

tracks skidding in the mud but making progress nonetheless. Well might Visconti

Prasca triumphantly cable later in the day, as Mussolini was in conference with

Hitler in Florence: ‘Our troops are proceeding with great enthusiasm across the

frontier.’

Peasants in the Greek frontier villages rushed from their

fields as the air shook with artillery fire and ran to huddle around their

fireplaces. Only the lucky few with radios had any idea what was happening.

Villagers gazed impassively at the Italians in their grey-green uniforms

tramping southwards through the damp and narrow streets. The Italians were just

the latest invaders of Epiros over the ages, after the Ottoman Turks, Slavs,

Goths, Gauls and Romans. These, too, would come and go. Thanks to this history,

each mountain village had its secret caves where the population could flee to

if things got really rough.

Papagos, ready or not, had to deploy what he had, and fast.

His defence plan included a transfer of the 13th and 17th Infantry Divisions

from the Bulgarian border to beef up the 8th Division, plus 16 Infantry

Brigade, though the units would need time to complete their transfer. These

divisions would be under the ultimate command of I Corps in Athens, while the

2nd, 3rd and 4th Divisions would muster east of the Pindos mountain range to be

sent to the front via Arta. Rather than split his forces to meet the two

separate waves of invaders, Papagos risked temporarily giving up some Greek

territory in order to maintain contact between his forces and forge a defensive

wall of men. Even so, Papagos’ front was more than 240km across, the 8th

Division alone responsible for some 100km. Time was impossibly short. National

mobilization was still far from complete. Men would have to be called up, given

basic training and sent into battle within days. Some of the delays in

preparation had been understandable. Metaxas, for cogent reasons, hadn’t wanted

to make the mobilization too obvious. Moreover, the Greek military had not

fought a war since the demoralizing Asia Minor debacle of 1922, and as a result

strategic and tactical thinking had not progressed much since then. For

Metaxas, however, the period of agonizing uncertainty had come to an end, and

he could throw himself into his task with a clear mind.

Bad weather over Albania and Northern Greece had grounded

all the Regia Aeronautica units based in Albania. But those bombers based in

southern Italy had no such impediment. Barely had Grazzi got back into his car

after delivering the Duce’s ultimatum when a squadron of Savoia-Marchetti SM81s

took off, appearing at 20,000 feet over the Royal Hellenic Air Force College at

Tatoi north of Athens around lunchtime. The sirens sounded in Athens again

around 9.30 am but no-one bothered to run to a shelter. The war was just too

exciting. The college commandant, Group Captain George Falkonakis, thought the

planes were Greek. Either the fine art of aircraft recognition had yet to be

taught in Greece or it took time for the RHAF officer corps to realize that

Greece was actually at war. Only when the first bombs came whistling down did

he order the sirens to be sounded and his flying cadets to don their helmets

and man the anti-aircraft guns. One of them was Constantine Hatzilakos, a keen

student flier barely into his first year at the air force college, finally

glad, as he put it much later, ‘to get into the fight’ even if not yet

airborne. Pilot Officer Doros Kleiamakis, a young flight instructor, was in the

air testing a French-made Bloch MB151 fighter when he puzzled over the black

puffs dotting the sky around him. Realizing what was happening, he managed to

land without getting hit by his own side’s anti-aircraft fire. Falkonakis’

delay in mobilizing the defences got him court-martialled.

On 1 November 1940 Metaxas personally ordered a night

bombing attack on the Italian position at Doliana, a few kilometres northwest

of Kalpaki. It was the first time the RHAF had flown operationally at night.

Three crews of Larissa-based 31 Bombing Mira (squadron) were selected. They

were frankly scared as they climbed into the cockpits of their French-built

twin-engine Potez 63s; none of them had ever flown a night mission, but Metaxas

was adamant that it be done, even if it were to prove fatal. After a half hour’s

anxious flight on instruments alone the mission leader, Pilot Officer

Anastasios Vladousis, successfully dive-bombed the lights of the Italian

columns, weaving away through the flak, followed by the others.

The RHAF, in fact, had a dual mission on its hands: to

defend Greek cities against bombing while acting as long-range artillery for

the army in Epiros. The former was the task of the air force’s four pursuit

mirai based (thanks to Metaxas’ foresight) mostly in central and northern

Greece. While the army was trying to absorb the Italian incursions in the

northwest, the Regia Aeronautica regularly bombed Greek strategic and civilian

targets, making little distinction between them. On 2 November the pilots of 22

Pursuit Mira based at Thessaloniki were scrambled to meet a formation of

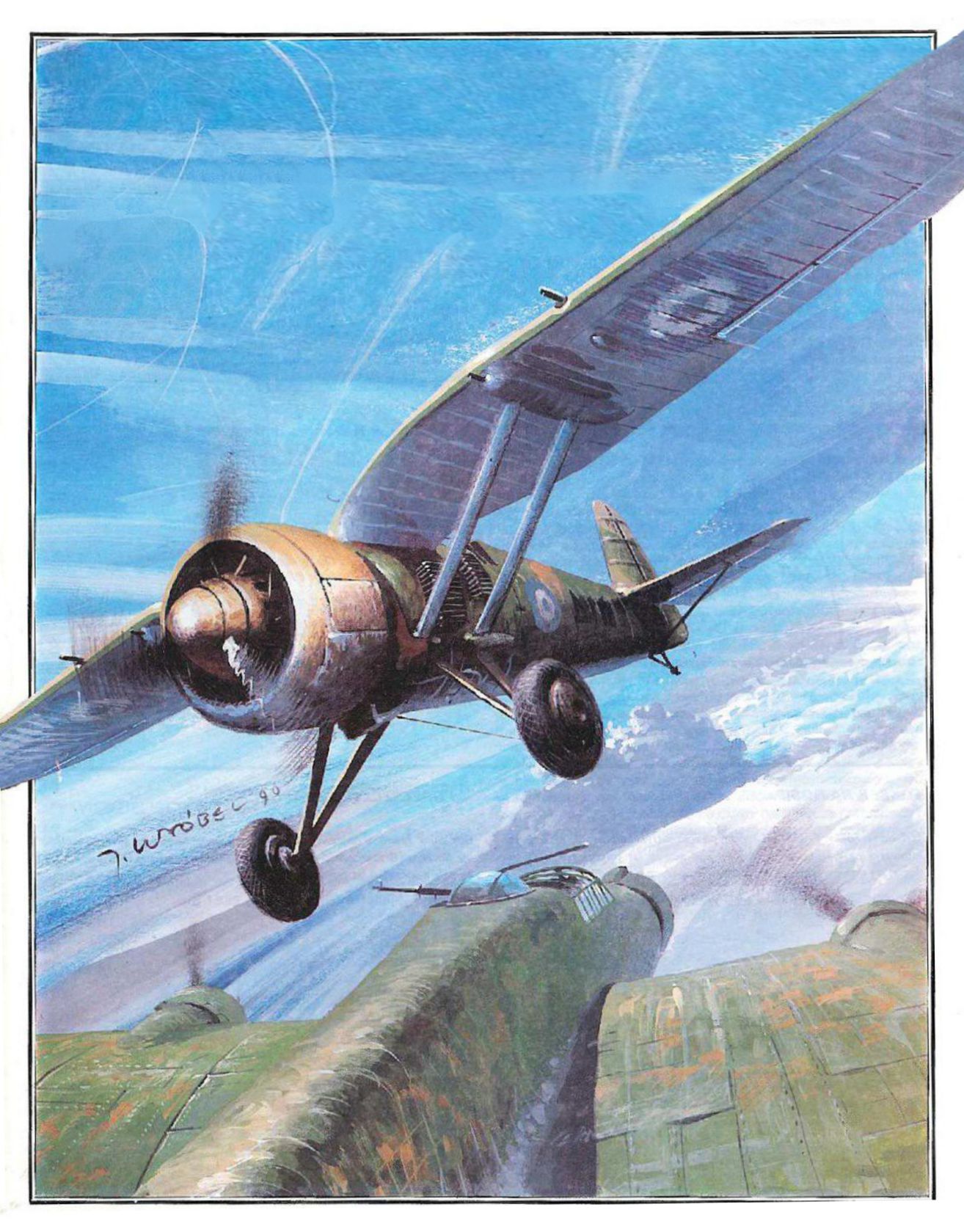

Italian bombers of 50 Gruppo converging on the city at 20,000 feet. Eight

Polish-built PZL24 monoplane fighters sporting the blue and white Greek roundel

climbed to meet them. Pilot Officer Marinos Mitralexis caught a three-engined

CantZ1007 – a sinister-looking machine painted in lizard-like camouflage – in

his gun-sight and sent a stream of 8mm bullets into it. Not seeing any

immediate effect, he pressed the firing button again, but found he was out of

ammunition. His next act, witnessed by an amazed wingman, was to aim his PZL

straight into the CantZ’s tail section. The impact sheared off part of one of

the twin rudders, throwing the plane into a spin. The crew – minus the pilot who

was apparently killed by Mitralexis’ initial burst – baled out.

Mitralexis, too, survived, having nursed his robust fighter

to the ground with surprisingly minimal damage. Once down, he found the Italian

crew seemingly about to be lynched by a mob of peasants. Drawing his pistol, he

warned the peasants off and personally led the enemy bomber crew into

captivity. Mitralexis’ ramming feat became an immediate cause celebre. Scores

of airmen, actual and aspiring, longed to be able to imitate him. (A few tried,

but were unlucky.) The RHAF College received a huge surge of applicants. The

sturdy PZL24, with its gull wing and raucous engine, became the object of

desire of every air cadet.

That same day Captain Luigi Mariotti was leading a dozen

Fiat CR42s of 363 Squadriglia on a bomber escort to Thessaloniki when they were

jumped by four fighters of 22 Mira. Sergeant Constantine Lambropoulos in his

fighter engaged the Fiats but soon had the worst of the encounter. As bullets

smashed into his plane from every side he tried to bale out but caught his

flying boot lace in the cockpit. With the plane plunging down vertically, his

chances of survival were rapidly dwindling to zero when a shell burst in the

cockpit, snapping the lace and allowing him to fall free. Seconds later the

plane disintegrated, and as Lambropoulos drifted down the Italians kept firing

at him – a contemptible practice which sullies the otherwise impressive record

of the Italian air force in the Greek campaign. He remained unpunctured, but

his parachute had more than fifty holes in it.

Savoia-Marchetti SM79 bombers of 107 Gruppo based at

Grottaglie raided Thessaloniki and Larissa, killing scores of noncombatants.

CantZs of 47 Stormo, including bombers skippered by Mussolini’s two sons, Bruno

and Vittorio, were met by defenders of 21 Mira but suffered no losses. In

retaliation, British-made Bristol Blenheim IV bombers of the RHAF 31 Bombing

Mira hammered the Italian air base at Korce inside Albania, killing nineteen

Italian airmen in the base operations room.

The Regia Aeronautica’s bombers might fly blithely over

Greek skies to bomb the towns and factories, but they seemed to be in short

supply over the front itself. Though Greek sources mention waves of Italian

bombers over the front, General Rossi, the Twenty-fifth Corps commander, fumed

at the perceived lack of air support on 4 November after the failure of the

first Italian attempt to break the line at Kalpaki. The Greeks, however,

reported shooting down two Italian aircraft on 5 November, as Italian artillery

renewed its bombardment of the Greek position. At about 10.00 pm the Siena and

Ferrara divisions launched a fresh assault, backed by about sixty tanks of the

Centauro. The attack was beaten back, with fifteen Fiats immobilized in the

bogs of the Kalamas River.

That evening Rossi felt he had to give his battered units a

breather. The staff of the 8th Division intercepted an Italian despatch that

graphically described what the invaders were up against:

The Greeks, known for

their stubbornness and persistence, have since peacetime organized the

naturally rough and uneven territory of Epiros with such method and diligence

that every rock is an artillery nest and every cave a defensive bulwark. [The

Greeks] are so fierce in battle that more and stronger means are required to

drive them off.

The RAF Arrives

The RAF put in a much-needed appearance to beef up the

slender resources of the RHAF. On 3 November 1940 whatever Air Chief Marshal

Sir Arthur Longmore, the RAF commander in the Middle East, could spare from his

forces began landing at Eleusis and Tatoi fields near Athens. These were,

initially, eight Bristol Blenheim I light bombers of 70 Squadron plus a few

battle-worn and already obsolete Gloster Gladiators of 30 Squadron. They were

later joined by four more Blenheims and Vickers Wellington bombers from 70

Squadron, which were at once sent into action to hit Italian supply ships in

the Albanian port of Sarande, across the strait from Corfu. The question of

accommodation became acute. Seven Greek generals had to give up their offices

in the Grande Bretagne to RAF officers. The RAF commander in Greece, Air

Commodore John D’Albiac, DSO, promised up to forty more bombers and thirty-five

fighters, not to mention much-needed batteries of 37mm Bofors anti-aircraft

guns for the RHAF airfields. Metaxas feared that not even that might be enough.

As the RAF began to bomb Italian shipping at Vlore and

Sarande, the Greeks were cheered by news of the Fleet Air Arm victory off

Taranto on 12 November, where the redoubtable British ‘stringbags’ – Fairey

Swordfish torpedo-bombing biplanes – decimated the bulk of the Regia Marina’s

heavy ships. But the RAF’s initial daylight raids on Vlore were proving costly.

On one of the first such attacks on the air base at Vlore, three Blenheim Is of

30 Squadron were met by the Fiats of 364 Squadriglia. Captain Nicola Magaldi,

the flight commander, drew a bead on the Blenheim skippered by Sergeant G. W.

Ratlidge and raked it with fire, killing the upper gunner, Sergeant John

Merifield. All three bombers, despite their extensive damage, managed to make

it back to Eleusis. Merifield was given a hero’s state funeral in Athens,

attended by the king and filmed by newsreel crews.

The appearance of the RAF meant that the Regia Aeronautica’s

air superiority was now about to be seriously challenged. But 364 Squadriglia

was in action again the following day, against a flight of 70 Squadron’s

Wellingtons over Vlore. Lieutenant Alberto Spigaglia and Warrant Officer

(Maresciallo) Guglielmo Bacci claimed credit for destroying two Wellingtons,

those of Sergeant G. N. Brooks, which blew up in mid-air, killing all on board,

and Flight Lieutenant A. E. Brian, two of whose crew parachuted into captivity.

Greek anti-aircraft fire on 9 November downed and killed Second Lieutenant

Pietro Janniello of 363 Squadriglia. Blenheims of the RAF’s 84 Squadron bombed

the squadriglia’s base at Gjirokaster and were away before the base fighters

could be scrambled properly.

The crash of the bombs falling on Athens’ industrial

districts and port of Piraeus, and the banging of anti-aircraft fire, became a

daily backdrop to the lives of young Sotiris Kollias and the other villagers of

Kalyvia. Sometimes the blasts would be loud enough to rattle windows. The

village and its neighbouring communities, in fact, provided a refuge for the

homeless of Piraeus and the bombed districts. ‘There wasn’t a house that didn’t

provide shelter to some family from Piraeus,’ Kollias recalled. Not that

Kalyvia itself was out of danger. Sotiris and his pals were playing in a field

when an Italian aircraft roared overhead spraying the kids with machine-gun

fire. By sheer chance no-one was hit.

Such hazards, however, were not much when compared with the

growing jubilation among all Greeks as the Duce’s armies were being pushed back

much sooner than anyone imagined. Greek state radio resounded to the sultry

voice of singer Sophia Vembo, who had since 28 October turned her talents from

romantic pop tunes to patriotic ditties. Even Italian songs were transformed

into Greek musical weapons. For example, ‘Regina Campanella’ was re-worded in

Greek to pour utter scorn on Mussolini, Ciano and anyone unfortunate enough to

be wearing a grey-green uniform. It became an immediate hit on the radio and in

packed theatres.