From the outset, and unlike the Greek Army, the Royal

Hellenic Air Force was heavily outgunned and outclassed, and would become more

so as the conflict progressed. At the outbreak of war the Regia Aeronautica

outnumbered the RHAF’s front-line strength by three to one. The Italian air

force at the time was one of the best-trained in Europe. Italy’s aerospace

industry, coddled by the Mussolini administration, was turning out redoubtable

aircraft such as the Fiat G50bis Freccia (Arrow) monoplane fighter, the Macchi

C200 Saetta (Lightning) fighter, the CantZ 1007bis bomber and the trimotor

Savoia-Marchetti SM79 and SM81 bombers. Many Italian combat pilots had honed

their air-fighting skills in the Spanish Civil War. In the 1930s Italy had

experienced a surge of interest in air sports and aviation in general,

encouraged by Mussolini’s own attainments as an aviator. It was part of the

Duce’s broader drive to re-mould the Italian people into a warlike nation like

the Romans of old.

The Regia Aeronautica had been an independent service since

1923. It was lucky to have contained pioneering thinkers such as Major Giulio

Douhet, who worked out the strategic bombing doctrines that would find their

full fruition later in the war. Marshal Italo Balbo refined Douhet’s ideas to

come up with the idea of a massed bomber force that could penetrate enemy

territory like a mailed fist. Balbo became hugely popular in Italy thanks to

his flying-boat team’s highly-publicized international flights, including a

tour of America. Well might Mussolini boast to his fascist party cadres on 18

November:

The Italian air force is always at the peak of its task. It has dominated and continues to dominate the skies. Its bombers can reach the most distant of objectives, its fighters are making life difficult for the fighters of the enemy. Its men are truly men of our time: their characteristic is a calm intrepidity.

Mussolini had some cause to boast. In terms of numbers,

aircrew and firepower the Regia Aeronautica looked good and was good. But what

he didn’t mention was that the senior air force command was ill-equipped to

aggressively command such a force. The air force Chief, General Pricolo, was

allowed nothing like free rein for his task. Worse, he wasn’t even told of the

plan to invade Greece until the critical high-level meeting of 15 October,

which he hadn’t even been invited to attend! One might justifiably wonder what

had happened to the innovative strategic ideas of Douhet and Balbo. The only

possible answer is that the attack on Greece was simply not conceived in air

terms. Visconti Prasca’s visions were of an exclusively army triumph; there was

also a lingering contempt for Greece and Balkan nations generally as not having

air forces worthy of the name, and hence not requiring specific air planning to

any major degree. Pricolo fretted at this, but seems not to have had the

strength of character to do anything about it – he, too, just wanted to keep

his job.

As the Greek air force was thought to be a flimsy adversary,

the Regia Aeronautica employed obsolescent biplane fighters in the first phase

of the Greece operation. About half of the available fighter force consisted of

Fiat CR42 Falco (Falcon) biplanes and older Fiat CR32s, the latter already at

the end of their career. The CR42 was about a match for the Greeks’ PZL24 and

Gladiator. Eighty examples of a newer all-metal monoplane fighter, the Fiat

G50bis, were available, plus twelve of the even better Macchi MC200. The

Italian bomber force included the menacing-looking three-engined Cant Z1007bis

Alcione (Halcyon), an aircraft that could take a lot of punishment and was

highly manoeuvrable. Fifty examples of the Cant Z506B Airone (Heron), a

seaplane version of the Cant Z1007, were also in service. Also lined up on

Albanian airfields were squadrons of Savoia-Marchetti SM81 Pipistrello (Bat)

bombers. The SM81 was in the process of being superseded by the sleeker and

more durable trimotor Savoia-Marchetti SM79 Sparviero (Hawk). Eighteen Fiat

BR20M Cicogna (Stork) twin-engined bombers were also operational. The Regia

Aeronautica’s planes were organized into squadriglie of nine aircraft each,

which was slightly smaller than an RAF squadron or Greek mira. Three

squadriglie made up a gruppo (somewhere between a squadron and a wing), and two

gruppi made up a stormo, or wing.

The Royal Hellenic Air Force had been an independent arm for

eleven years, producing its first crop of nine graduating aircrew officers in

1931. Through the politically turbulent 1930s the fledgling air force had

experienced its ups and downs. Both the army and navy looked down on the

upstart service as little more than a flying club for well-to-do young men. The

RHAF College, known as the Icarus School, had narrowly escaped being closed

down in 1932. The air force’s survival was assured only in 1934 with the

creation of the General Air Staff. Still, even in 1940, Greek air operations

were under the full control of the army, in the person of Major General Petros

Ekonomakos.

On 28 October the RHAF could field four air observation and

army cooperation mirai, three of naval cooperation aircraft, four of fighters

and three of medium bombers, totalling some 160 planes, though perhaps

two-thirds were serviceable. The main fighter was the Polish-built PZL24, a

rugged machine but rapidly being outclassed in Europe. Before the war Greece

had managed to buy a dozen modern Bristol Blenheim IV bombers and another dozen

single-engined Fairey Battles from Britain, and a similar number of Potez 63

bombers from France. The naval cooperation mirai had the advantage of modern

British Avro Anson patrol bombers. When war broke out Greece had ordered 107

additional modern aircraft such as the redoubtable Supermarine Spitfire, the

American Grumman F4F Wildcat and the Martin Maryland bomber. It never got to

receive them.

The immediate operational need of the RHAF was to repel the

waves of Italian bombers while employing the army observation squadrons to keep

track of the invading Italian land forces. The fighters had an unequal fight on

their hands from the start. The first real aerial encounter of the war took

place on 30 October, when a few Henschel Hs126 observation aircraft took off to

locate Italian troop formations and had the worst of an encounter with five

Fiat CR42s. One Henschel went down, killing its observer, Pilot Officer

Evangelos Giannaris, the first Greek airman to die in the campaign. Another

Henschel went down that same morning, killing its two-man crew, while Italian

bombers hammered the port of Patras.

The Greek aircrews learned how to fight the hard way. ‘We

didn’t know how to fly then,’ said Flying Officer George Doukas of 24 Pursuit

Mira later. ‘We couldn’t even shoot. We knew nothing of firing distances or

angles of attack. We went to war … as if we were on parade. We were blown out

of the sky.’ Greek pilots had very little, if any, training in evasive

manoeuvres. To compound the problem for the Greeks, the Italian bombers would

come in at high altitude – at least 20,000ft – which was at the limit of the PZLs’

and Gladiators’ operational ceiling. It was a rare sortie that didn’t see some

Greek airborne casualty.

Units of the crack 53 Land Fighter Stormo (Wing) had arrived

at bases in Albania on 1 November – 150 Gruppo (Group), comprising 363, 364 and

365 Squadriglie. Their pilots were a bit disappointed in having been given the

Fiat C42s to fly, especially as the stormo had specifically trained for the new

Macchi MC200 fighters, and were naturally quite proud of the fact. But the

Macchis were kept safe at Turin while the older biplanes were fed into the war

against Greece. While 365 Squadriglia was transferred to 160 Gruppo Autonomo at

Tirana, 364 was stationed at Vlore and 365 at Gjirokaster, sometimes

interchangeably.

As the Siena, Ferrara and Centauro Divisions were advancing

on Kalpaki, Metaxas himself telephoned the RHAF’s bomber chief, Group Captain

Stephanos Philippas, at his headquarters at Larissa. An enemy column was

rolling towards Doliana, Metaxas barked, and had to be stopped that very night

‘even if no-one comes back’. Philippas detailed a flight of 31 Bombing Mira to

do the job. The 31 Mira CO, Flight Lieutenant George Karnavias, gulped. None of

his crews had ever flown a night operation before. But orders were orders. As

night fell, three of his pilots climbed into their twin-engined Potez 63s and

headed off into the mountain blackness. One of them was Flight Lieutenant

Lambros Kouziyannis, wounded in the head on the previous day’s mission. He

jumped out of his hospital bed to join the operation, ignoring the protests of

his CO.

The pilots’ only guide on the way, apart from their glowing

instruments, was the dim candlelight from the clifftop Meteora monasteries to

starboard. The crews had to shield their eyes from the bombers’ white-hot

exhaust shooting from the engine housings. The lights of an Italian column

approaching Kalpaki became visible as the Potez 63s roared over Ioannina and

its shimmering lake. Kouziyannis, his head bandaged, bombed the column, defying

a hail of flak on the dive. On his way back he got lost and found himself over

blacked-out Athens rather than his base at Larissa. His bomber ran out of fuel

over the city, but managed to glide the few miles to the base at Tatoi. He had

just cleared the airfield fence and was breathing a prayer of thanks when he

collided with a parked trainer in the darkness. The concussion crippled

Kouziyannis for the rest of his life.

As the Italians continued to bomb Thessaloniki and other

cities, killing scores of civilians, Greek bombers sometimes gave as good as

they got. Early in November 31 Bombing Mira took off from Athens to bomb the

Italian base at Korce. A formation of Blenheims under Flying Officer

Constantine Margaritis pounded the base, killing nineteen airmen who had

gathered in the ops room for a briefing, and wounding twenty-five others. Two

Italian fighters were damaged on the ground. The Fairey Battles of 33 Mira were

equally audacious, sneaking into Albanian airspace and shooting up Italian

columns. Those planes, though, were primitive. The pilot of a Battle could

communicate with his gunner/observer in the back only through a speaking tube –

engine noise permitting, of course. Maps were scarce; the only available map of

southern Albania had to be rotated among several crews.

The Fiats of 365 Squadriglia continued tangling with the

inexperienced Greek airmen, to the latters’ cost. On 4 November Second

Lieutenant Lorenzo Clerici and Sergeant Pasquale Facchini pumped streams of

bullets into a couple of Breguet XIXs of 2 Air Observation Mira that were

strafing the troops of the Julia Division, sending one of them spinning down in

flames.

Greece’s three bombing mirai, 31, 32 and 33, were only

gradually introduced to the principles of tactical air warfare. Their task at

the outbreak of war was to act as long-range artillery in support of ground

operations, a task made easier as the RAF gradually took over the strategic

bombing of enemy targets in Albania. These missions took a steady toll of

aircrews. One of the Blenheim IVs of 32 Mira was downed over Gjirokaster on 11

November. The Blenheim IV was one of the few modern bombers in the RHAF’s

armoury and the loss of even one was significant at a time when the Regia

Aeronuatica, in response to the Italian setbacks in the ground war, poured some

250 more fighters into its Albanian bases. Metaxas confessed to having

nightmares about the erosion of the air force’s firepower.

The main reason why the Greeks had to advance quickly on the

eastern part of the front to capture Korce was that it was a base from which

Greece’s cities were being regularly bombed. The Blenheims of 32 Mira and

Battles of 33 Mira were sent to soften up Korce on 14 November, in advance of

the Greek III Corps thrust, destroying fifteen enemy aircraft on the ground in

two waves, for the loss of one more 32 Mira Blenheim – probably to one of

Italy’s more renowned airmen, Second Lieutenant Maurizio di Robilant of 363

Squadriglia. Flight Lieutenant Panayotis Orphanidis was returning to Larissa

from the Korce raid when he found a Fiat CR42 stuck on his Blenheim’s tail,

firing intermittently and weaving to get a better shot. The Blenheim was the

faster plane, but it couldn’t quite shake off the pursuer. More than 160

bullets smashed into the bomber’s fuselage and wings, holing the fuel and oil tanks,

which luckily were nearly empty, and wounding the gunner. Orphanidis knew that

the Italian would have his best chance as the bomber slowed down to make the

turn to land at Larissa. So instead of making the turn he continued on and

across the eastern Greek coast, setting a course for Sedes base at

Thessaloniki. Somewhere over the water the Fiat, apparently low on fuel, gave

up the chase.

As Orphanidis and his friends were trying to flatten the

Korce base, six of the smaller and more agile Battles of 33 Mira swept at low

level from Corfu and snaked between the mountain ranges to stage an audacious

raid on the Gjirokaster base. Despite the flaming wall of flak they had to

penetrate, not one Battle was hit (though 363 Squadriglia reported a damaged

‘probable’). Typical of the effect on the RHAF’s morale was a letter by Pilot

Officer Yannis Kipouros to his mother after the operation: ‘I know that one day

I might plunge to earth defending my beautiful country,’ he wrote. ‘What are

the Italians defending? … The joy I feel when completing a mission is

indescribable.’ Kipouros (who was to disappear without a trace on a mission in

a few weeks’ time) was venting a more general optimism among the Greeks, as

mid-November was seeing the tide turn on the ground, with the Julia Division

knocked out and the rest of the Italian army stalled before Kalpaki.

The RHAF’s army cooperation and observation mirai were

active in their obsolescent but hardy Henschel Hs126 monoplanes, strafing and

harassing Italian columns inside Albanian territory. A large Italian bomber

force struck at the advanced Greek base at Florina, the headquarters of 31

Mira, but without hitting a single aircraft or major installation. The 31 Mira

CO, Squadron Leader Grigorios Theodoropoulos, wondered whether the enemy were

‘just unlucky, or inexperienced and hasty’.

While the Greek drive on Korce was getting up steam, the

Fairey Battles of 31 Mira were ordered to hit the Italian forces on Mount

Morova and Mount Ivan, the high points defending the southern approaches to the

town. The raid was not unopposed. Performing prodigies of flying in this sector

was di Robilant of 363 Squadriglia who scored a devastating hit on Flying

Officer George Hinaris’ plane, killing his gunner/observer and forcing him to

bale out, his flying suit on fire. Hinaris was saved by falling into a stream,

though he was badly burned. In the same action Di Robilant accounted for Flight

Lieutenant Dimitris Pitsikas’ Battle, which managed to limp to a landing at

Ioannina, though by that time Warrant Officer Aristophanes Pappas, the

gunner/observer, was dead in the back seat. While that was going on, three

Potez 63s of 31 Mira attacked enemy artillery positions in the Devoli River

valley. Vladousis’ plane was hit by his own side’s anti-aircraft guns. His

gunner/observer already dead, Vladousis jumped from the stricken plane into a

maelstrom of fire from the wheeling Fiats and the Greeks on the ground. To

identify himself to the latter, he took a letter from his mother from his

pocket and as he floated to earth he waved it like a white flag, yelling, ‘I’m

Greek, you fellows!’ at the top of his voice.

Once down, he was saved from toppling over a cliff by a

sergeant whom he recognized as an old school friend. As Vladousis was chatting

with the local sector colonel, the captain of the offending anti-aircraft

battery burst in with profuse and embarrassed apologies. The officer, it

seemed, had no idea that the RHAF had twin-engined bombers such as the Potez 63

in the air – all he knew about, apparently, were the antique Breguet XIXs.

Anything more modern than that, it was assumed, had to be Italian. Relaxing,

Vladousis took off his flying overall and in that way he told the army

something more about the indomitable spirit of the air force, for underneath it

he was wearing his full dress uniform. To the thunderstruck colonel Vladousis

quipped, ‘Since we never know if we’re going to come back, we might as well

dress properly.’ Just as many airmen carried (and still carry) personal

talismans as psychological defence mechanisms against worrying too much about

death, the dress uniform was almost Spartan in its significance. It was like

Leonidas’ Spartans combing their hair before the fatal encounter at

Thermopylai. So Vladousis, if he was going to meet death, was determined to do

it with dignity.

Two days before the fall of Korce 32 Mira was sent to bomb

the base at Gjirokaster. Pilot Officer Alexander Malakis, perhaps because of a

navigation error, bombed nearby Permet by mistake. The attack flattened an Italian

military hospital, killing at least fifty patients. Next door to the hospital

an ammunition dump exploded and burned for three days. While Malakis and his

crew were decorated for the raid, Rome howled about a gross violation of the

Geneva Convention. What actually happened is disputed to this day. Malakis

claimed to have bombed by mistake, as Permet resembled Gjirokaster. The Greeks,

moreover, asserted that the ammunition dump – ostensibly the real target – had

been deliberately placed next to the hospital to deter attacks. This

‘explanation’, however, implies that Permet could have been the legitimate

target after all. And certainly there was no lack of Greeks in uniform whose

memories of Italian aggression were quite fresh and thus not overly scrupulous

about what they hit.

The suddenness of the Greek advance on Korce caught the

Regia Aeronautica by surprise. Hours before the base’s capture, a SM79 bomber

collided with three Fiats while trying to take off. It was abandoned to the

Greeks who repainted it with blue and white roundels and added it to their

bomber force. The Battles of 33 Mira were sent to harass the retreating Italian

column but came under attack by a swarm of Fiats which forced the Greeks to

break off the operation. One Battle was seriously damaged and its

gunner/observer wounded.

The undoubted heroics displayed by the outgunned RHAF drew

the admiration of Metaxas, but he fretted that the loss rate could not be

sustained for very long. Even with the help of the RAF from the early days of November,

and even when the ground campaign began turning in the Greeks’ favour in the

middle of the month, the air war was giving Metaxas serious jitters. Grateful

as he was for what British aerial help could be spared from the Middle East

theatre, he could only gloomily observe his own airmen and planes dwindling

mercilessly.

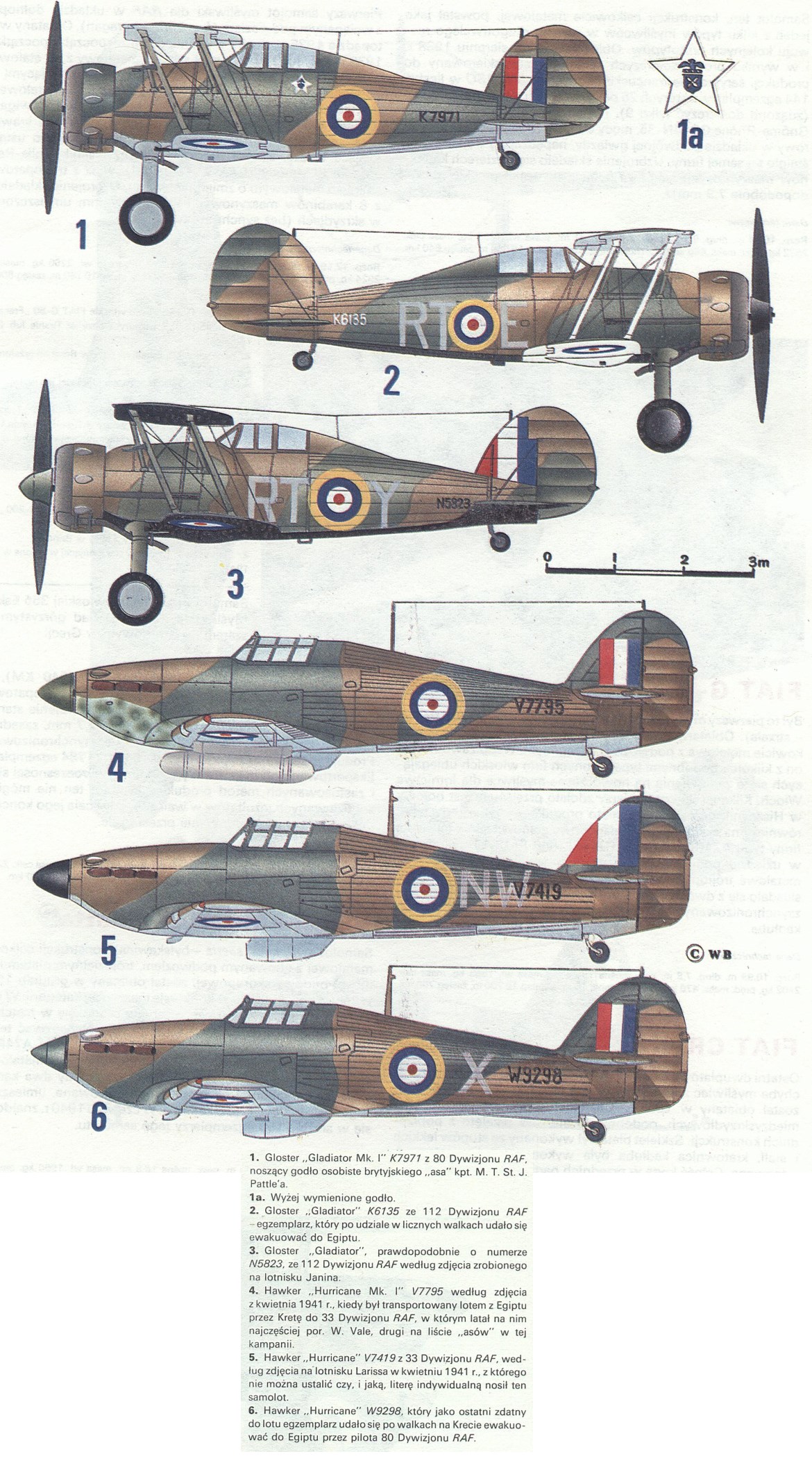

More British aerial help arrived on 18 November in the form

of 80 Squadron, equipped with Gloster Gladiator IIs. Led by Squadron Leader

William Hickey, the fighters touched down at Eleusis along with a lumbering

Bristol Bombay transport carrying ground crews and spares. From that day the

boys in RAF blue were given hero status by the grateful Athenians.

Understandably, the crews that first night took full advantage of the adulation

in the form of endless free drinks and meals, but Hickey himself wasn’t free to

join in the fun, having to receive his orders from the Greek High Command.

These were for 80 Squadron’s B Flight under the South African-born Flight

Lieutenant Marmaduke ‘Pat’ Pattle to fly on to Trikala in central Greece the

next morning, refuel, and carry out the RAF’s first fighter patrol in Greek

skies.

Pattle and his flight, plus his CO Hickey, landed at Trikala

to find the crews of the RHAF’s 21 Pursuit Mira ‘enjoying a meal of bread and

cheese and olives … washed down with a very strong-smelling but sweet-tasting

wine,’ which they shared with the Britons.6 Thus fortified, three of 21 Mira’s

PZL24s led Hickey and nine of 80 Squadron’s Gladiators on their first

familiarity flight over the northwest Greek mountains. By the time the

formation reached the Italian base at Korce the PZLs had to turn back because

of a lack of fuel, leaving B Flight to see what it could pick off.

The eagle-eyed Pattle, leading the flight’s second section,

was the first to see four Fiat CR42s of 150 Gruppo climbing to intercept them

and signalled to Hickey. As both pilots went into an attacking dive, the Fiats

scattered. Pattle got onto the tail of one of them and coolly blasted it at

100yds – the first of the redoubtable South African’s many kills in the Greek

and Albanian theatres of the war. Over Korce airfield Pattle expertly evaded an

attack by a 154 Gruppo Fiat G50 monoplane fighter, of the kind that was now

being fed into the campaign in increasing numbers, and a few minutes later

downed another CR42. At that point low air pressure knocked out the Gladiator’s

guns, so he had to fly wildly around the sky getting out of the way of

aggressive Italians until the gun pressure could build up again, but by that

time his fuel was low and at tree-top height weaved his way through the

mountains to Trikala, where 80 Squadron was feted as having accounted for nine

Italian fighters and a couple more probables. As a reward, the pilots were put

up at Trikala’s best hotel.

After that triumphant RAF debut, the weather stepped in.

Constant rain for forty-eight hours, and low-lying dense cloud for another

forty-eight, held up all operations. Nonetheless, on 25 November Pattle took up

half a dozen Gladiators to patrol the Korce area, but couldn’t entice any of

the enemy to tangle with him. The next day B Flight of 80 Squadron was ordered

to move to Ioannina, where conditions were drier and the battlefront nearer. In

a clear but freezing sky Pattle’s section spotted three SM79 bombers escorted

by twelve CR42s well inside Greek airspace. As the section under Flight

Lieutenant Edward ‘Tap’ Jones dived on the bombers, Pattle led his own six

planes against the Fiats, which tried to fight back, but abandoned the

encounter after Pattle had sent two of them spinning into the ground on fire.

It was during these first encounters that Captain Nicola

Magaldi, the CO of 364 Squadriglia who had fired the shots that killed Sergeant

Merifield in his Blenheim, was jumped by nine of Hickey’s Gladiators and killed

in his turn (perhaps by Pattle himself), to be awarded a posthumous gold medal

for valour. The following day ten Fiat CR42s of 364 and 365 Squadriglie found

themselves entangled with more Gladiators just south of the Albanian border.

One Fiat and one Gladiator collided in the melee, killing both pilots. (The RAF

victim was probably 80 Squadron’s Flying Officer Bill Sykes, the first British

fighter pilot to die in the Greek campaign.) Captain Giorgio Graffer, the

commander of 365 Squadriglia, was killed (posthumous gold medal award) – the

second 150 Gruppo squadron commander to be killed in as many days. Two Fiats

and one Gladiator were lost, with two more Fiats and three more Gladiators

damaged.