GERMAN COUNTERMEASURES AGAINST AIRLIFT OPERATIONS

By Army and

Counterintelligence Agencies

Attacks on Partisan

Airfields.

The Army security troops and police units committed in the

rear areas of Army Group South, Center, and North were’ often supported by

aircraft and antiaircraft units provided by the Luftwaffe as well as by air

force headquarters troops employed for ground combat. In the course of their

anti-partisan operations, these troops attempted to seize the airfields used

for resupplying the partisans. Since these airfields were located in

partisan-infested areas in fairly inaccessible forests and swamps, and since

they were furthermore well secured and defended, they could usually not be

attacked on the ground. By the time a major German unit, after serious

fighting, finally succeeded in penetrating to such an airfield, the aircraft and

installations had already been destroyed. Destruction by artillery fire usually

failed because of the difficulty of bringing the guns sufficiently close to the

target or because of a shortage of ammunition. Sometimes, however, a major

operation of this type was rewarding, as when the Germans succeeded in

capturing an airfield in the Lepel area on which there were more than 100

Soviet cargo gliders.

Deceptive Measures.

The German ground forces had a certain amount of success in

imitating landmark beacons of the Russians by setting up similar fires and

flares. In this manner the Germans succeeded in several instances in seizing

air-dropped supplies or in making Russian aircraft land within their territory.

For example, during an anti-partisan operation conducted south of Lake Ilmen in

the winter of 1941–42 by a reinforced German infantry regiment, the troops

fired the same flares as the partisans, whereupon Russian supply aircraft

dropped parachute containers enclosing ammunition, rations, and PX supplies. The

principal achievement, however, was that the Russians grew far more careful

after that.

In February 1942 counterintelligence agents of Eighteenth

Army captured a sabotage detachment composed of 8 men near Tosno (59° 33’N 30°

53’E). During his interrogation one of the radio operators stated that they

were expecting an aircraft with a new commander and a new radio operator.

Moreover, he informed his interrogators that the light signal to be given at

the time of arrival of the plane above a small lake was the Russian letter “G.”

Upon request from the Germans, the radio operator contacted the Leningrad

station and found out that the plane would arrive the following night. At the

indicated time the area was surrounded by German troops. The aircraft landed on

the ice with four men aboard. While the two pilots were able to shoot

themselves, the two passengers were captured alive.

But the Russians did not always fall into such traps, as is

shown in the following case. In the spring of 1943 the 318th German Counterintelligence

Group staged a similar operation in the Surash forest, some 20 miles north-east

of Vitebsk (20), hoping to seize an aircraft that supported the Partisan

Brigade Sokolov. The plane actually arrived, but instead of landing it strafed

the area and dropped bombs. On their return trip the Russians who were working

for the Germans on this mission fell into an ambush prepared by Sokolov’s

partisans. The cause of this failure was never established. Although the

Germans had used proper signals and code messages, the central partisan staff

probably became suspicious because the clearing in the forest indicated by the

Germans had not yet been used for landing operations. The Germans could not

have used the customary airfield because all access roads were mined and the

field was too close to the camp of Brigade Sokolov.

The German counterintelligence agents were able to obtain

some of the partisan-destined supplies by playing German-prepared codes into

partisan hands.

Such deceptive measures probably did not interfere much with

the airlift of supplies to the partisans. Interference from the air was far

more promising.

By Luftwaffe Agencies

Attacks on Jump-off Bases and Partisan Airfields. The

Russian advanced landing fields, generally known to the Germans, were in the

principal sector of Army Group Center as follows:

“1941–43: Kaluga (about 100 miles south-west of Moscow),

Sukhinichi (approximately 70 miles north-west of Bryansk), and Kalinin (about

95 miles north-west of Moscow);

1943–44: Konotop (about 110 miles north-west of Kiev) and

Sechniskoya (between Bryansk and Roslavl).“

The German Air Force units did not launch any mass attacks

on these airfields; they made nuisance raids instead, mainly because they

lacked sufficient strength to do better. These units also had other targets in

the combat zone that had higher priority than airfields serving partisan

support.

Again because of the shortage of forces the Germans were

unable to launch planned offensives against partisan airfields, even in the

central sector of the Russian theater.76 They were forced to improvise measures

against these targets. Nuisance bombers had orders to drop bombs in their raids

on these well-known airfields, if such action promised results. Bombers were

also ordered to attack such airfields as a secondary-mission. But only in a few

instances did the Germans score successes in bombing raids on partisan air-drop

points, and the number of Russian aircraft shot down in such raids was small.

To restrict Soviet night flying activities that were

constantly increasing, the security divisions of Army Group Center were each

issued three close reconnaissance aircraft, model Focke-Wulf. After a slow

start they proved very effective. They succeeded, for instance, in identifying

the well-camouflaged and forest-hidden emergency airfield at Zezersk

[Chechersk], north-west of Gomel, at a time when a plane was on the field. It

was destroyed on the ground and another one was later shot down while landing.

The airfield was then destroyed during a special operation and made

inaccessible, after bombing from the air had proved of little lasting effect.

At the end of 1943 the close reconnaissance units of the 1st

Air Division committed in the Central Army Group sector at Mogilev were

employed in the partisan-held area to the west with orders to fire at every

light signal. If the pattern of light signals indicated the existence of a

landing field, the German planes were to wait for Russian aircraft to land,

then drop flares and set the enemy planes on fire.

During the period 1 September 1943 to the summer of 1944 an

air commander (Brig.-Gen. Punzert) on the Sixth Air Force staff was responsible

for committing his auxiliary bombing units not only for night nuisance raids on

nearby enemy forward areas but also for supporting anti-partisan operations of

the ground forces and attacking Russian supply aircraft. These auxiliary units

received their personnel and equipment from flying schools. They were organized

as follows:

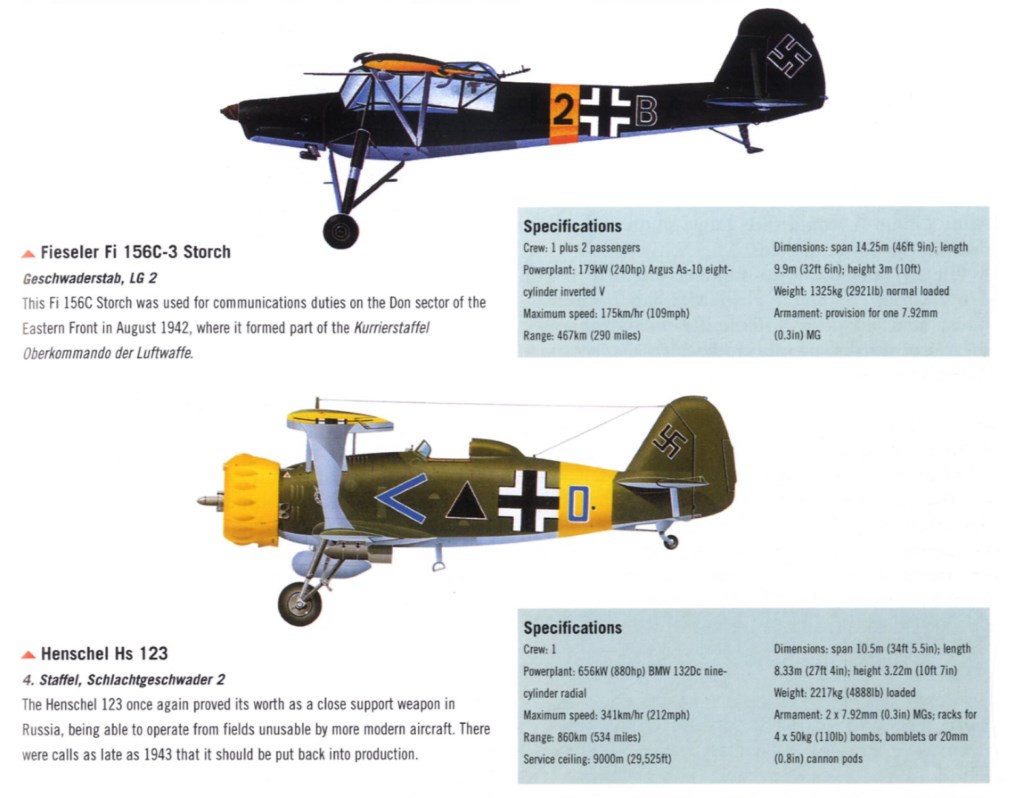

(1) 1st Night Ground Attack Group with 5 squadrons, equipped

with the following model aircraft: Arado 66 (single-engine school and training

planes of an old type), Heinkel 45 and Henschel 126 (antiquated, single-engine

reconnaissance aircraft), and Focke-Wulf 189 (twin-engine close reconnaissance

planes).

(2) Combat Command Liedtke, consisting of 3 squadrons,

equipped with Junkers F 13 (single-engine, commercial aircraft), Henschel 123

and 126 (antiquated, single-engine close reconnaissance aircraft), Heinkel 111

and Dornier 17 (antiquated, twin-engine bombing and long-range reconnaissance

aircraft), and Messerschmitt 109 (single-engine, single-seat fighter).

(3) Special Squadron Gamringer (for reconnaissance and

combat) composed of 12 planes of the following models: Arado 66 (single-engine

school and training planes of an old type), Junkers 87 (dive bomber), and

Messerschmitt 109 (single-engine, single-seat fighter).

The armament of these planes was improvised with machine

guns, while the Focke-Wulf 189’s and Heinkel 111’s also had cannon. Bombs were

dropped by hand, except for the Heinkel 111’s which were equipped with bomb

release and bomb sight devices.

The commitment of the few aircraft suitable for night

fighting against the approaching supply transports failed, although not through

any lack of personnel. The aircraft were insufficiently equipped with

navigational aids, their armament was unsatisfactory, and the pilots had not

had enough training in firing guns. The aircraft warning net did not offer

sufficient coverage and the Russians adroitly exploited this weakness. For

these reasons the Germans had to be satisfied with keeping the areas through

which the Russian aircraft entered their territory under surveillance. This was

achieved by tracing the fiery glare of the engine exhaust until the landing of

the aircraft and then bombing the landing ground. This procedure was only

rarely successful, because the partisans improvised an antiaircraft defense of

the landing fields. At first they responded with immediate and intensive rifle

and machine gun fire; after a while, they also used light antiaircraft guns

with considerable success. Only in 2 or 3 instances were the Germans able to

establish that they had destroyed Russian aircraft on the ground.

The 1st Night Ground Attack Group was committed along the

northern sector of the Russian front, under the command of the 3rd Air

Division, from the beginning of 1943 to 6 July 1944. The group flew night

bombing missions against nearby targets such as troop assemblies, tank-staging

areas, motor-vehicle columns, and artillery positions. Originally designated as

a nuisance bombing group, the group was equipped with inferior and partly

unarmed school and training aircraft and antiquated close reconnaissance

planes, and could therefore be employed against these targets only by night.

When partisan activities in the immediate rear of the combat zone, especially

in the partisan-infested area south-west of Leningrad around Luga, required

anti-partisan operations in September 1943, individual planes of this group

were committed as reconnaissance and bombing planes in support of the ground

forces in daytime missions.

South of Luga the partisans had prepared a landing field for

supply transports—model U 2—in virtually inaccessible terrain. The borders of

the landing surface were surrounded by piles of twigs that were lit when

Russian supply planes were expected. One of the Heinkel 46 aircraft succeeded

in arriving at precisely that moment and attacked a U 2 with machine-gun fire

as it was landing. The crashed aircraft was sighted the next day. Constant

disruption of their supply system must have created great difficulties for this

partisan unit, since the Germans intercepted radio messages indicating that the

partisans were unable to operate for lack of supplies.

In the southern part of the Russian theater the Germans also

had to improvise. Thus, in 1943–44 Russian aircraft, even twin-engine types,

landing on partisan-prepared airfields on the high plateau of the Yaila

Mountains, were attacked by German auxiliary units equipped with school and

training planes.

Attacks on Transports in Flight. Since the supply aircraft

flew only under cover of darkness, it was difficult to combat them with flak

and fighters. In contrast to Western Europe, the Germans in the Russian theater

had a weak night-fighter organization.

In the Sixth Air Force area in the central sector, the II

Corps and the 1st Air Division had improvised a night-fighter intercept

organization against Russian supply transports. Radar intercept detachments

were installed on railroad cars and thus given the necessary mobility for

commitment at enemy points of main air effort in accordance with German air and

railroad capabilities. These detachments were instrumental in scoring the

greatest number of night kills; but their number was insufficient to achieve

more than very limited local coverage.

Deceptive Measures.

The small U 2, a slow but maneuverable aircraft, used by the

Russians to carry supplies into areas close to the front, was suitable for

night missions because the German night fighters could not easily shoot it

down. Moreover, it could take off from and land on small airstrips that could

be found in great number. It could also land on skis wherever such landings

were possible. These airstrips were known to the German Air Force and new ones

could rapidly be identified by air reconnaissance units. The Soviet command,

however, did not have to make frequent switches in landing, supply, or airdrop

fields because the German ground forces were too weak to seize them and the

German night fighters were not very effective in attacking them.

By constant surveillance the German command sometimes

succeeded in identifying the signal markers on landing grounds. Night fighter

and reconnaissance aircraft provided data for deceptive measures to mislead

Russian supply aircraft approaching by ground orientation markers. Along a

frequently used Russian air-supply route in the Sixth Air Force area the

Germans reconnoitered a landing field at the rear border of an area of the

front that was firmly controlled by the German ground forces. This field was

“prepared for landing,” and occupied by an air force liaison detachment and one

light antiaircraft platoon. On the basis of frequently observed landing signals

at partisan airfields, a list of signals was established for the liaison

detachment and the night reconnaissance aircraft that was to observe and radio

the proper signal for the respective night to the liaison detachment. The

personnel of the latter thereupon set up the lamps in the proper pattern so

that the approaching Russian supply transports would assume that they had

arrived at destination and would land.

The success of this type of deception depended on the

following:

(1) The “trap” had to be along the approach route because

the Soviet aircraft had sufficient means of ground orientation to detect major

deviations from their course.

(2) The trap could not be too far ahead of the destination

since the crews would notice major differences in flight time. On the other

hand, it had to be sufficiently far from the point of destination so that the

two signals could not be seen simultaneously from the air.

(3) The light signals could not be made up of the customary

flashlights, but had to consist of lanterns or straw fires as used by partisans

at their airfields. The strong while light of electrical flashlights would have

aroused the suspicions of the Russian crews.

Because of the requirement that such traps be set up close

to the real landing field, the successful use of this deceptive measure was

limited. Use of this measure was also limited to clear nights during which such

navigational aids as ground orientation markers consisting of fires would

permit the moderately trained and primitively equipped Russian crews to fly

such missions. Nevertheless, such traps were at times successful;86 in one

instance, six aircraft of a U-2 squadron landed at short intervals and were

captured by the Germans. A seventh plane escaped, the pilot probably becoming

alarmed because the preceding aircraft had not been brought under cover with

sufficient speed.

Radio was sometimes, though more rarely, utilized. The

following report pertains to a case of particularly successful radio deception:

“As I remember, Army

Group Center in 1944 maintained a separate situation map on the partisan-held

area west of Mogilev and around Lepel, where German police units and Hungarian

elements operated. These partisans regularly received airlift supplies,

according to these situation reports. For this purpose, the partisans had built

several airfields in the midst of extensive forests, where aircraft landed at

night under improvised illumination. The Russians used mainly R-5 model

aircraft. I can remember an experience report, of which we received a copy,

describing an operation against several of these airfields. An Air Force

officer had discovered the airfields and had captured one after the other so

that he could signal down the arriving aircraft during subsequent nights, using

the prearranged code signal for landing. He then seized the aircraft and their

cargo. The officer was decorated with the Knight’s Cross for this action. It

must have been in the spring of 1944.”

CONCLUSIONS

The preceding description of Russian partisan warfare

against the German invaders indicates that this type of warfare inflicted heavy

damage, both in personnel and matériel, on the German Armed Forces. It also

tied down strong forces that had to be denied to the frontline fighting proper.

Partisan warfare may have contributed considerably to the German defeat.

The conditions which made the successful conduct of partisan

warfare possible were as follows:

(1) Russia’s tremendous size, bad roads, and the many

possibilities for hiding in the extensive forests and swamps that were

available even to large partisan units.

(2) German inability to capture the numerous Russian

soldiers, whose units were dispersed after the initial battles and the armored

breakthroughs which followed. These men went into hiding behind the German

lines and rapidly formed large combat-effective partisan units.

(3) The ability of the first partisan units to arm and equip

themselves from the enormous quantities of matériel that had remained on the

battlefields; also their ability to live off the land.

(4) The abundant energy and brutality demonstrated by

partisan leaders of all ranks.

(5) The Russians’ highly developed ability to improvise,

their primitiveness and their frugality.

(6) The Russians’ patriotism, which is so great that they

will make any sacrifice; their fatalistic attitude; the conviction, inculcated

into them, that their communist “achievements” were endangered; all these

characteristics contributed to their self-sacrificing spirit.

(7) Last but not least, the false propaganda and poor

treatment of the Russian civilian population by German political leaders

created resistance instead of maintaining and exploiting the advantage of the

initial confidence displayed by many elements of the population, as for

instance in the Ukraine, where the Germans were received as liberators.

The partisan units could not have continually increased and

improved their arms and equipment or have fought and trained and carried out increasingly

complicated missions, however, without airlift operations. These assured a

steady flow of weapons, ammunition, explosives, fuses, and, wherever necessary,

rations, clothing, signal equipment, POL supplies, staff and headquarters

personnel, training personnel, specialists, and agents. The airlift also

provided courier service for written and oral orders and directives, propaganda

for the partisans and the civilian population, military mail service, and other

means of maintaining combat effectiveness and morale.

This leads to the conviction that impeding or at least

strongly-hampering airlift operations would have stopped partisan warfare

altogether or weakened it to such an extent as to obviate its significance in

the struggle.91 As described in the preceding pages, the Germans did not

succeed in disrupting the airlift operations to a degree that would have put

the flow of partisan supplies in question. Despite a few partial successes in

anti-airlift operations, the Germans were generally no more successful in this

field than in anti-partisan warfare on the ground. What were the reasons for

this failure?

The Germans had neither sufficient fighter nor antiaircraft

units at their disposal properly to combat the Russian air force units in the

German rear areas. In order to combat the supply transports flying exclusively

under cover of darkness, the Germans needed night-fighter units for

interception and the necessary equipment for the direction of interception from

the ground. Such auxiliary measures as have been described caused a certain

amount of disruption, but did not lead to any decisive success because the

“auxiliary units” had neither the planes nor the training, nor were there

enough of them. Efforts to hamper the Russian airlift operations by attacking

take-off and landing fields in partisan-held areas could be carried out only by

emergency units and were therefore doomed to failure. Combat units were

urgently needed in the combat zone itself and could be made available only

occasionally and then only for nuisance raids.

The command for anti-partisan operations was unsatisfactory

and ineffective because no top-level staff was in charge of the Army and Air

Force elements, the SS and police forces, the counterintelligence, and other

units used for anti-partisan operations. Although the Germans were aware of

certain Russian preparations for partisan warfare even before the outbreak of

hostilities, no timely preparations were made except for the activation of Army

security divisions to protect the lines of communication and the organization

of special SS and police forces. But no individual or staff was responsible for

the overall command of anti-partisan operations. Whereas the Russians had put

one man in charge of the entire partisan warfare operation, the Germans

suffered from internal difficulties and overlapping responsibilities. Neither

local nor specific spheres of responsibility had been established, let alone

general ones.

The so-called rear area commanders of each army group were

responsible for securing and pacifying the occupied territories and

administering and exploiting their areas. Only too late, in autumn of 1943, was

the rear area commander of Army Group Center, which suffered most from partisan

activities, redesignated “Armed Forces Commander.” Whether he actually was

given command over all units that were to be committed against partisans in the

area under his jurisdiction seems doubtful. But to fight partisans successfully

when they become as powerful and as numerous as in the Russian campaign, one

must have absolute command authority over all security, reconnaissance, and

combat units that are needed for anti-partisan operations. Moreover, these

units must be available in sufficient number and strength.

1942- One Last Opportunity: The German Experience with Indigenous Security Forces