British, American and Australian troops lunching in a wood near Corbie the day before the attack at Hamel.

Early in July, now under General John Monash, the Diggers win a model victory with his new tactics. Weeks later the AIF and Canadians lead an Allied attack which inflicts a resounding defeat on Ludendorff’s army. In the ensuing offensives, the advancing AIF carves a corridor of victories. With pace and initiative, the Australians keep piercing strong defences, and finally they break the Hindenburg Line. Controversy from these gruelling days, and the last experiences of the Diggers, complete our odyssey with these big-hearted Australians. The defeated Kaiserreich surrenders, and 11 November 1918 is a historic day for the AIF and the navy.

By the end of May, the Australian Corps of five hardened divisions had a new commander: John Monash, the gifted citizen-soldier. Born in Melbourne a year after his Jewish parents arrived from Prussia, he became the most outstanding German-descent Australian in the AIF. After Gallipoli he trained and led the new 3rd Division, and its performances against the Germans were soon earning the respect of the older divisions. Broadly educated, with a brilliant mind and fresh ideas, Monash was highly effective and insisted on the careful, practical follow-through of plans – which he communicated clearly. Building on his experience and the limited-objective method of attack, he was ready to expand into bigger offensives, where all available weapons and the latest technology would work together for maximum effect.

Attack on Hamel-Vaire 1918, by A. Henry Fullwood

Hamel

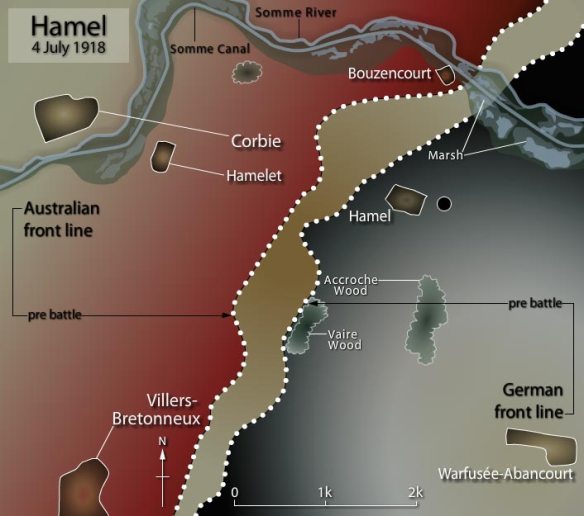

Monash showed an early interest in the new, improved Mark V tank, and if he could get these, with extra artillery and aircraft assistance, he knew he could take Hamel (5 km north of Villers-Bretonneux) and its nearby strongpoints. But with Germans on the Wolfsberg ridge, right behind Hamel, watching the preparations, and a flat battleground for the Diggers to cross, Fritz had such defensive advantages that a Gough-style attack would have been cut to pieces. Monash understood this, and was the last man who would order a rush-and-hope job. He even altered his original, tank-dominant plan to satisfy MacLagan’s 4th and 11th infantry brigades. The 4th had been decimated in Gough’s tank fiasco at Bullecourt, and 15 months later its men still hated tanks. So did most Diggers. But Monash and the tank chiefs showed the men what damage these better, stronger Mark V tanks could do and see what they could withstand; the Diggers trained with them and soon took a liking to them, as the infantry’s concerns and problems were given high priority, and a new confidence was built.

Artillery and aircraft were employed in a variety of ways, and low-flying aircraft made a lot of noise for several days to cover the sound of approaching tanks. And there were Yanks as well as tanks. Adopting their celebrated 4 July as the day of battle, Monash and Rawlinson acquired some US companies to be attached to all ten Australian battalions, and the Diggers became tutors to these enthusiastic Americans. The arrangement was good for everyone, as Ted Rule wrote:

It bucked our lads up wonderfully … the novelty of war had long vanished for our boys [and] before such a fight one now sees only set grim faces, but on this occasion, everyone was smiling … they were determined to let the Yanks see what Aussies were capable of …

Unfortunately, Pershing heard about this breach of his policy, and most of the Americans were belatedly pulled out. “Those with my platoon had to withdraw,” said Rule, “and I never saw such disgust and disappointment in my life. Our boys were just as disappointed”. But with a timely display of backbone (which put the wind up Rawlinson) Monash insisted it was too late to pull out the last four companies of Americans, and they took part in the battle.

Zero hour was 3.10 am, and 300 guns flashed in the pre-dawn fog. Aircraft flew in “swarms” while the infantry and tanks advanced with the creeping barrage, but despite Monash’s coordination, his exemplary all-arms attack could not be all like clockwork. At the formidable Pear Trench, when the tanks got lost, the Diggers reverted instantly to their old ways. Henry Dalziel, a Gallipoli veteran, led the way in furiously attacking and silencing machine-gun nests. Uncut wire also faced other Diggers, who didn’t wait for their tanks, and got through a gap under fire. Cpl Thomas Axford’s blood was up, and he attacked the machine-gunners with bombs and bayonets, killing ten and capturing others, who were happy to be prisoners. Both Axford and Dalziel won the VC. Meanwhile the Mark Vs were not idle. To the Diggers’ delight they were smashing machine-gun posts. At the Wolfsberg objective, the tanks rumbled forward, crushing and blasting the last machine-gun obstacles. The Diggers charged in, capturing dugouts containing scores of men and a headquarters. Impressively, the 90-minute plan was carried out in 93 minutes. Over 1000 Australians and 176 Americans were casualties, but the enemy lost 2000 dead and wounded, 1600 prisoners and weapons galore.

As a key player within a cooperative all-arms attack, the Mark V tank was a roaring success. Rawlinson and many a BEF general realised that these greatly-improved tanks, working together with the other fighting elements, could make a huge difference. Out of one well-defended German trench, which survived the artillery, 26 machine-guns were excavated – after a single tank had crushed that trench. While saving heavy infantry losses, tanks could support more momentum on the battlefield, as well as having their own ferocious impact. This, and above all Monash’s skilful coordination of his “all-arms offensive” (like conducting some lethal orchestra) provided a sound model that inspired confidence, and many a BEF commander hastened to study it in anticipation of coming offensives.

The Supreme War Council, including Clemenceau, Lloyd George and a host of Allied leaders – which happened to be meeting at this time – were delighted by this auspicious victory. Congratulations began flowing to Monash and the AIF, but the old “Tiger” delivered his personally. On the following Sunday, he came and stood before a gathering of the Diggers, and said:

When the Australians came to France [we] did not know … you would astonish the whole continent … I shall go back tomorrow and say to my countrymen ‘I have seen the Australians … I know that these men will fight alongside of us again until the cause for which we are all fighting is safe for us and for our children.’

Der Schwarze Tag – “the black day” of the German army

If Hamel, for the Australians and for Rawlinson, augured well for the Allies’ big Amiens battle in August, a truly stunning affirmation of the Allies’ prospects was delivered soon afterwards. It was Foch’s counter-offensive of 18 July, which transformed the Second Battle of the Marne. This tremendous blow, by 5 August, had sent the Germans reeling back 40 km, and out of the entire Blücher salient they’d earlier seized.

In combination, the Second Marne and Amiens victories would pave the way to a vast Allied counter-offensive, which would inflict almost continuous defeats on the Kaiserreich’s armies. Anglophone history says little – too little – about the Second Marne, but Ludendorff heard too much, and he blamed the “surprise” of 18 July on France’s “small, low, fast tanks” attacking with their mounted machine-guns through the wheat fields. There was a lot more to it than that. On 18 July alone, the main attack had eighteen divisions (four times as many men as all the Diggers in France) led by those 300 light tanks; and on its flank nine more divisions and 145 tanks joined in. At Hamel, Monash had used about 2.5 per cent of Foch’s resources, but his two brigades had 60 heavy British tanks. Thus, Monash’s ratio of tanks to men had been stronger, and it suggested to British commanders what might be done in future. Demand soon overtook production, maintenance and transport facilities; and there were other problems, such as attrition among the limited supply of tank men. Before all that, however, the improved Mark V tanks would have their greatest success on 8 August, east of Amiens, where almost every Mark V in France participated.

“August 8th was the black day of the German Army in the history of this war.” In this famous line, at least, Ludendorff’s memory was accurate, for the German army was never as impressive again. But the disaster happened on his watch, and in his 1919 memoirs, he was quick to shift the blame – onto the troops, of course. They should have coped, he wrote, because they were in good shape. He had to say that because, on the eve of battle, he’d given them this ill-informed and arrogant assurance:

… we occupy everywhere positions which have been very strongly fortified … Henceforth, we can await every hostile attack with the greater confidence [and] we should wish for nothing better than to see the enemy launch an offensive.

Whether this reflected complacency or ignorance – “very strongly fortified” was not the description his troops would have used for their shallow and inadequate defences – the Allies had a much better idea of how things might go. Rawlinson’s main concern was Haig who, having got over his big fright of March and April, reverted to his old ways and called for another distant objective, 43 km away. Rawlinson hadn’t forgotten the bad old Somme days, when Haig had rejected his offensive plan, imposed distant goals, dissipated the artillery’s effectiveness and caused the disaster of 1 July 1916. This time, however, Haig’s intervention was contained, and did not waste the formidable power and accuracy of the BEF’s 1918 gunnery. Rawlinson was careful to humour the chief by inventing a job for his obsolete cavalry, which in Haig’s dreams might still ride to glory. At Amiens in August, the initial aim was to drive the Germans well away from the city and its railway hub; but Rawlinson, Monash and others wanted to do more, and deliver “a stunning blow to German morale.” This they achieved, so well that the battle is still described as “the BEF’s greatest victory of the war”.

It was a victory spearheaded by the Australians and their Empire comrades, a point Ludendorff himself made, in a distorted way. The battle began “in a dense fog [when] the English, mainly with Australian and Canadian divisions [attacked] with strong squadrons of tanks, but otherwise in no great superiority” – and yet his men “allowed themselves to be completely overwhelmed”. Allowed themselves? As if they could have chosen to repel this terrific assault; they were outnumbered as well as outgunned. But Ludendorff didn’t want to know what it was like to be one of his weary soldiers, who had somehow just survived a deadly shelling, and now found himself in the path of the war’s heaviest tank attack; or what it was like to be in a trench as a 29-ton Mark V tank bore down on him, and his armour-piercing ammunition (if his platoon had any) simply bounces off the monster.

The attack drove east along the Somme, with the British III Corps fighting north of the river. The Australian Corps stretched from the south bank, on a starting line that ran past Hamel right down to the outskirts of Villers-Bretonneux. On their right, below the railway were those solid Dominion cousins, the Canadians, and alongside them was a larger French force. In the Australian line, the 2nd and 3rd Divisions attacked side by side, and later, to maintain momentum, they were leap-frogged by the 4th and 5th Divisions. The 1st Division, brought back to rejoin the rest, was in reserve. “All the Australians were gathered together,” Jimmy Downing recalled, “and we had the advantage of being with men on whom [we] knew we could rely”.

Among the 2nd Division was Joe Maxwell and his irrepressible mate Doc, hard fighters who somehow always survived. When the sun broke through, one German pilot seemed bent on ending their lucky streak. His aircraft machine-gunned them and then dropped a cluster of bombs with deadly effect, but Joe and Doc slowly emerged, covered in dust, but still intact. Next day, the fight on the ground got just as close and personal. Joe’s company lost thirteen of its sixteen officers, but, after winning a bar to his MC (as he later heard) Maxwell was still in one piece, as well as Doherty.

When the battle ended, the achievement south of the river had been astonishing. The Australians, Canadians and French had shattered the German army across their 25-km front. The Dominion troops had broken stiff defensive efforts and powered so far forward that they were now more than 20 km east of Villers-Bretonneux. Just as they’d done at Hamel, but this time with their entire Corps, the Diggers had been all over Fritz, capturing him and his guns. Monash had told them they were about to “inflict blows upon the enemy which will make him stagger” and they had done even more. Within hours, jubilant Diggers were calling out “G’day Fritz” and “You were lucky” to flocks of prisoners heading to the rear. By early afternoon, the Australians had captured over 7000 Germans and 173 of their guns. They were also ready to work with the Canadians. Elliott’s 15th Brigade gave exemplary support in one hot action – during which Pompey got his ample backside grazed by a bullet. With his trousers down, Elliott had himself patched up while continuing to shout out his directives. The sight of their burly brigadier “with his tailboard down” amused his soldiers mightily. Later the superb Canadian general, Currie, told Monash, “there are no troops who have given us as loyal and effective support as the Australians”.

Over four days, the Allies took 499 guns and 30,000 prisoners, while more than 40,000 enemy troops were wounded or killed. Seven German divisions were “completely broken” and Ludendorff saw his hopes of victory (and the Kaiserreich’s dreams of conquest) disappear. “Our only course,” he wrote, “was to hold on”. Fearing a collapse of morale on both home and battle fronts, he dared not retreat all the way to the Hindenburg Line. As his reinforcements marched up to the front, some of the mauled survivors were calling out to them, “You’re just prolonging the war”. This, in the German army, shocked Hindenburg and Ludendorff, and they knew the game was up: the 8 August battle had “put the decline of [our] fighting power beyond all doubt” and a comeback was impossible.

“The war must be ended,” Ludendorff concluded, but this end had to be delayed. It was – and hard fighting continued, on a large scale. Despite lowered morale and indiscipline along the supply lines, most German troops were in essence loyal to a Fatherland which might soon suffer an Allied invasion. This built-in patriotism, in effect, maintained (for some three months) the support for that Prussian regime that had deceived and exploited them. Fritz, therefore, remained a tough opponent, and the Allies still assumed that final victory would not arrive until mid-1919. As for the Prussian warlords, they needed the German soldier to defend stubbornly, above all at the Hindenburg Line – to secure tolerable peace terms, whenever the ultimate Schwarze Tag arrived.