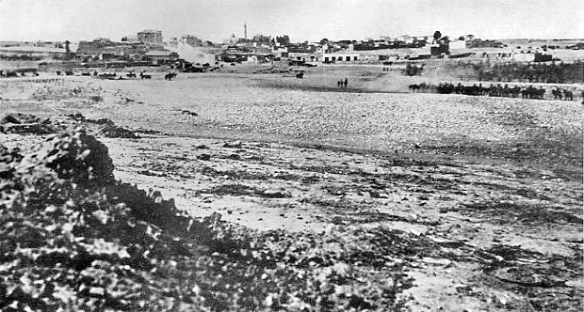

The town of Beersheba in Palestine, 1917. Captured by Australian light horse on 31 October 1917 during the First World War.

By 1 p.m., the 60th Division (less the 2/22nd Londons, digging in on Point 1069) had taken all of their objectives, about a mile and a half beyond the Ottoman trenches. The 74th Division had been delayed by having to send forward wire-cutting parties, but were able to declare their own objectives achieved only moments later. Acting Corporal John Collins of the 25th Battalion, Royal Welsh Fusiliers took a leading role in the attack, and was one of the first to enter the Ottoman trenches and engage the enemy hand to hand. During the 74th Division’s long march under fire he had repeatedly risked himself to rescue the wounded and bring them back under cover, and after the final assault he led a Lewis gun section out beyond the objective, giving covering fire for his unit as it consolidated its position and reorganised their scattered men. For his ‘conspicuous bravery, resource and leadership’ throughout the day, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Over all, resistance had been lighter than expected. Although well sited, the Ottoman lines were thinly held, and once the British infantry had closed to bayonet range the 67th and 81st (OT) Infantry Regiments had been unable to resist the weight of numbers thrown against them. As the final assault started, as many Ottoman units as possible were withdrawn in good order back towards the town, and for the moment no British pursuit was mounted. After their night march and morning’s action, the troops badly needed to rest, quite apart from the need to re-form themselves after the advance. On top of this, it had been decided that the Desert Mounted Corps should be the ones to actually take the town, as they would be in greater need of the water. In fact, only the 230th Brigade of the 74th Division would see any further action, at dusk as they advanced north to cut the Beersheba to Tel el Fara road. At 9.40 p.m. the divisional commanders received news that the town had fallen into British hands at 7.40 p.m.

While the infantry had been coming on from the south-west, the cavalry had attacked from the east. Theirs had been a long ride to get into position, and Lieutenant Briscoe Moore of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles found that:

The early morning hours of darkness are the most trying, for then vitality is at its lowest and fatigued bodies ache all over. Then comes the first lightening of the eastern sky, and the new day dawns with a cheering influence, which is increased as the next halt gives the opportunity for a hurried ‘boil-up’ of tea; after which things seem not so bad after all to the dust-smothered and unshaven warriors.

The A&NZ Mounted Division had advanced to the north-east of Beersheba. The New Zealand Mounted Rifles (NZMR) Brigade had turned towards the eastern side of the town, with the 1st ALH Brigade slightly behind them in reserve. Meanwhile, the 2nd ALH Brigade carried on north and pushed back the 3rd (OT) Cavalry Division, capturing the Ottoman post on Tel el Sakaty at noon, and from there cut the Hebron road by 1 p.m. This road would later also be cut much further north, about 32km (20 miles) north-east of Beersheba, by a small but heavily armed party of about seventy cameliers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Newcombe of the Royal Engineers. Newcombe had already established a reputation for daring independent action with the Sharifian forces in Arabia, and on the night before the attack he had led his force out of Bir Asluj as far north as they could reach. Armed with ten heavy machine guns and a number of Lewis guns, his men established themselves across the Hebron road late on 31 October and proceeded to create as much noise and destruction as possible, attacking passing convoys and cutting the telegraph lines. He had hoped to attract local tribesmen to rise up and aid him, but was disappointed in this. Even still, his force held out until 2 November, created much confusion (giving the Ottomans the impression that the British intended to advance on Hebron) and drew off small but significant Ottoman forces to deal with him. Eventually the force was overwhelmed after taking 50 per cent casualties. Newcombe was taken to Constantinople as a prisoner, although he would rapidly escape with the aid of a French lady whom he later married, and lived free in the city for the best part of a year. This amazing character deserves to be better known.

The A&NZ Division then began to advance in towards Beersheba at shortly before 9 a.m., and the NZMR Brigade and the 3rd Australian Light Horse Brigade (attached from the Australian Mounted Division) were told off to attack the dominating height of Tel el Saba. Around 300m (1,000ft) high at the time, the tel sat at the convergence of two wadis, and these would provide the key to taking the position (as well as a source for a small amount of water for the horses). They provided the only decent cover in the area and led directly to the tel, but even so, it would prove a tough nut to crack. A battalion of the 48th (OT) Infantry Regiment was well dug in, with machine-gun and artillery support, and excellent fields of fire. The Auckland Regiment NZMR was first into action, supported by the Somerset Battery RHA. Their 11th Squadron rode along the wadi bed to about a mile from the tel before dismounting and beginning to advance on foot, coming under heavy machine-gun fire from the tel, and from a smaller hill slightly to the east of it. The other two squadrons – the 3rd and 4th – managed to close to about 800m (875yds) from the tel before being forced to dismount in the wadi. The Canterbury Regiment NZMR came up on their right flank, while the Somerset Battery opened fire from around 3.2km (2 miles) away, at which range their fire was too inaccurate to be very effective. The 3rd ALH Brigade advanced on their left, and at 10 a.m. the 1st ALH Brigade was also committed to the attack. An hour later the Inverness Battery RHA added their fire to the barrage, and under the cover of this the Somerset Battery advanced, halving their own range and improving their accuracy. This battery was being directed by the commander of the Auckland Regiment, and the regimental history records that, after this move:

No time was lost in correcting the range of the guns, a signaller with flags passing on the messages given to him orally by the Auckland colonel. It was only a matter of minutes before several changes in the range were flagged back, and the shells were bursting right over the machine-gun emplacements of the enemy. ‘That’s the stuff to give ’em,’ ejaculated Lieutenant-Colonel McCarroll as he saw the goodly sight.

Immediately this remark was sent back as a message by Lieutenant Hatrick, who doubtless had his tongue in his cheek as he did so. After the fight the battery commander, an Imperial* officer, inquired who sent this message. ‘I could not find it in my book of signals,’ he said, ‘but I would like to say that we understood it perfectly, don’t you know.’

As the barrage gained effectiveness, the attack moved closer in short dashes under galling machine-gun fire. New Zealand and Australian troopers converged on the tel from the north, east and south, and at 2.40 p.m. the smaller hill was captured, along with sixty Ottoman soldiers and two machine guns that were turned onto the tel. With this additional covering fire, the Aucklands rose for a final dash. Briscoe Moore recorded:

The line then commenced to move forward, first one part advancing covered by the fire of the others, then another section. The ground, being more or less broken, afforded fairly good cover, but the Turkish artillery made good shooting and put over many good bursts of shrapnel which whipped the ground amongst the advancing New Zealanders into myriad spurts of dust. The engagement thus developed until the attacking line was perhaps two or three hundred yards from the Turks, when heavy fire was exchanged from both sides. Then the New Zealanders charged with fixed bayonets, pushing the attack home with great determination as they mounted the rising ground towards the enemy. The sight of the cold steel coming upon them was evidently too much for the morale of the Turks, for their fire died down as our panting men approached their trenches, and those that did not bolt soon surrendered. Thus was another victory added to the record of the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade.

The Ottoman forces had already begun to withdraw towards the town as the final assault swept over the tel at 3 p.m., but even so seventy prisoners and two machine guns were captured. The way now lay clear for the advance into Beersheba itself.

However, time was beginning to become an issue. The remains of the Ottoman forces were consolidating in the town, and were in a position to easily blown the wells should either wing of the British attack resume its advance. Meanwhile, dusk was approaching, only two hours away. The next move had to be not only decisive, but also swift, and Chauvel turned to his last uncommitted cavalry formation, the Australian Mounted Division under Major General Henry Hodgson. A brief consultation followed. The 5th Mounted Brigade was probably best suited to make a mounted charge into the town; they were equipped with swords and trained for fighting from the saddle. However, they were several miles away, and with time of the essence it was decided to use Brigadier General William Grant’s 4th ALH Brigade instead. Although unsaddled and dispersed, they were close at hand and well rested having seen no action yet during the day. Although no water had been found for the horses, some feed had been issued to them. At 3.45 p.m. Grant ordered his men saddle up and form up, and called his senior officers together for a briefing. They would have to cross several miles of open ground, swept by artillery and machine-gun fire, and then tackle a crescent-shaped system of trenches just south of the Wadi Saba. This system consisted of several lines of trenches, but thankfully had no barbed wire protecting them.

At 4.30 p.m. his forces were ready. The 4th ALH Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel Murray Bourchier) were on the right, with the 12th ALH Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel Donald Cameron) on the left. Each was drawn up in three lines, each of a single squadron, with their headquarters, signallers and ambulances behind. Within each line, each trooper was spaced at about 4 or 5m (4 or 5yds) from his neighbours, so that a single burst of machine-gun fire or shell would not cause too many casualties. The gaps between the squadrons was 300m (330yds), giving plenty of time for the riders coming up behind to swerve around any fallen men or horses in front of them. Behind the two leading regiments, the 11th ALH Regiment was held in reserve. The 5th and 7th Mounted Brigades were also ordered to come up with all haste to support the attack, while the Notts Battery RHA and ‘A’ Battery HAC provided covering fire.

As the advance started, two German aircraft swept out of the sky to bomb and strafe the advancing ranks, but with little effect. Instead, the advancing squadrons, beginning at the walk, sped up into a trot. Artillery, long-range machine-gun and rifle fire was now falling among them, but the advance remained steady and sedate, making sure that the formations remained together for maximum impact. Closer to the enemy, they broke into a canter, and finally a gallop for the last few hundred metres. The fire of all calibres was heavy and intensive now, but the Australians had two advantages: the dust thrown up by their horses’ hooves, and the speed of their advance. As panic and urgency gripped the Ottoman defenders, many forgot to adjust the sights of their weapons. These had been set high initially for the long-range fire, but as the troopers got closer many forgot to lower their sights, sending their bullets and shells high over the Australians’ heads. According to one study, most of the weapons recovered after the charge still had their sights set at 800m (875yds). However, enough accurate fire was being laid down, and the horsemen faced additional dangers from steep-sided wadis, rifle-pits and trenches, all of which could easily disable a horse. Sergeant Charles Doherty charged with the 12th ALH:

As the long line with the 12th on the left swung into position, the rattle from enemy musketry gradually increased in volume … After progressing about three quarters of a mile our pace became terrific – we were galloping towards a strongly held, crescent shaped redoubt of greater length than our own line. In face of this intense fire, which now included frequent salvos from field artillery, the now maddened horses, straining their hearts to bursting point, had to cross cavernous wadies whose precipitous banks seemed to defy our progress. The crescent redoubt – like a long, sinuous, smoking serpent – was taking a fearful toll of men and horses, but the line remained unwavering and resolute. As we neared the trenches that were belching forth death, horse and rider steeled themselves for the plunge over excavated pitfalls and through that tearing rain of lead.

Trooper J. ‘Chook’ Fowler, in one of the following lines, captured the confusion of the charge:

The level country near the trenches was deep in dust. This was one of the worst features of the Palestine Front, for six months each year without rain. The horses in front stirred up the dust and we could see only a few yards, our eyes almost filled with dust, and filling the mouth.

The artillery fire had been heavy for a while. Many shells passed over our heads, and then the machine-gun and rifle fire became fierce as we came in closer to the trenches some of the Turks must have incorrectly ranged the sights on their rifles, as many bullets went overhead … The machine-gun fire was now very heavy. I felt something hit my haversack and trousers and later, on inspection, I found a hole through my haversack and two holes in my trousers. One bullet left a black mark along my thigh. Some horses and riders were now falling near me. All my five senses were working overtime, and a ‘sixth sense’ came into action; call it the ‘sense of survival’ or common sense. This said, ‘If you want to survive, keep moving, keep moving,’ etc. So I urged my horse along, and it wasn’t hard to do so as he was as anxious as I was to get past those trenches … No horseman ever crouched closer to his mount than I did. Suddenly through the dust, I saw the trenches, very wide with sand bags in front; I doubt if my horse could have jumped them with the load he was carrying, and after galloping two miles. The trench was full of Turks with rifle and fixed bayonets, and hand grenades. I heard many grenades crash and ping-g-g-g-g over the noise of rifle and machine-gun fire. About 20 yards to my left, I could just see as a blur through the dust some horses and men of the 12th Regiment passing through a narrow opening in the trenches. I turned my horse and raced along that trench. I had a bird’s eye view of the Turks below me throwing hand grenades etc. but in a flash we were through with nothing between us and Beersheba, and the sound of machine guns and grenades behind.

The 4th ALH met the thicker sections of trenches and became embroiled in clearing them, using their bayonets as swords or dismounting to clear the trenches hand-to-hand. It was hard, grim work but many of the Ottoman defenders were stunned by the suddenness and brutality of the attack. The 12th ALH met with less resistance and fewer trenches; parts of their leading squadron dismounted to clear those they encountered while the two following squadrons sped on into the town. At 4 p.m. Ismat Bey had ordered a general withdrawal of the forces in Beersheba, and the effect of the Australians, even if now in small, scattered groups, erupting through the streets was immense. Ismat Bey barely escaped, while most of his staff and the papers in his headquarters were captured. The Australians rounded up over a thousand prisoners, and captured nine field guns and three machine guns. The 11th ALH, coming up behind, carried on through the town and pushed the last Ottomans out of the northern parts. Ismat Bey was only able to stop the retreat and begin re-forming his men some 8 or 9.5km (5 or 6 miles) north of Beersheba, although it took days to properly re-establish his corps.

Beersheba had fallen. A few demolition charges had been set off by the Ottomans, but the wells were taken largely intact, but unfortunately proved not to as prolific as thought. Barely enough was found to water the mounted divisions, and over the next two days the cavalry and infantry carried out small, limited attacks north and east of the town to secure further sources. The infantry had to remain reliant on water convoys from the rear. In the town, the work to clear up after the battle began. Patrick Hamilton helped to collect and treat the wounded:

In the operating tent our medical officers worked steadily and almost in silence. Continuous skilled surgery hour after hour. Anaesthetics, pain killing injections, swabs, sutures, tubes in gaping wounds, antiseptic dressings, expert bandaging. The medical orderlies did a fine job assisting.

Stretcher bearers were standing by for the change-over. Two on either side lift the stretcher clear of the stands, and replace with the next patient all within two minutes. The pace never slackened!

Here, out in the field at night, surgical work of the first order was performed. This was the 4th Light Horse Field Ambulance at work! About 2 a.m., after six hours of dedicated work by all hands, the last of our 45 wounded was put through. All patients by now were bedded down under canvas and made as comfortable as possible. Most slept through sheer exhaustion or under drugs. We arranged shifts and lay down on the hard ground fully clothed for a few hours’ rest.

In total, over 1,500 prisoners had been taken. During its charge on the town, the 4th ALH Brigade had suffered surprisingly light casualties – two officers and twenty-nine men killed, and four officers and twenty-eight men wounded. The 60th Division had suffered three officers and sixty-seven men killed, and thirteen officers and 358 men wounded. On the Ottoman side, the III (OT) Corps had been almost destroyed, although they had no reason to feel ashamed. While accusations and recriminations flew between the corps and Kress von Kressenstein, with the fact that the corps had a high proportion of Arab troops being often cited as a reason for its ‘poor’ performance, they had in fact behaved admirably. The Ottoman lines had held against great odds and heavy attacks through most of the day, longer than the British had thought they would. It was only the late, desperate charge of the 4th ALH Brigade that had finally shattered their lines.

With Beersheba taken, attention now turned to the western end of the line, and the great fortress town of Gaza.