Map showing schematic of proposed German Fleet raid of October 1918 and possible British response.

In early 1918, the future seemed brighter than at any other time during the war. After Russia collapsed in 1917, Germany dictated a peace with Russia in March 1918 and with Romania two months later. These agreements gave Germany direct or indirect control of huge territories on its eastern border and in the Balkans. Thus, the dreams of many annexationists seemed to be coming true. After this victory in the east, the Imperial High Command was also confident that it could risk playing its last card in the west by launching a new offensive, `Operation Michael’, in March 1918. With this offensive, the High Command hoped to gain victory before US troops arrived on the continent and turned the numerical scale in favor of the Allies. Despite great initial success, the offensive finally ended in military disaster and defeat, culminating in the famous `black’ 8 August 1918. Slowly, the German armies, which were exhausted after four years of fighting and whose strength was dwindling at an alarming rate, had to retreat on the Western Front. The Allies proved overwhelming in terms of numbers and, more important, materiel. At last, on 29 September, the Imperial High Command, which had slowly begun to realize that the war was lost and that the army, whose soldiers had already begun a `hidden military strike’, was broken, had no choice but to admit defeat and ask the government to negotiate an armistice.

While a newly appointed coalition government, which even included leading Social Democrats, tried to pave the way for peace, the Supreme Navy Command, which had been established only in August, drew different conclusions from these events. Forced to give up unrestricted submarine warfare in mid-October, its chief, Admiral Scheer, regarded these developments as an almost golden opportunity for a final sortie against the Grand Fleet. Against the background of its nearly complete lack of success during the war, the Supreme Navy Command believed that only a gallant fight could justify the build-up of a powerful new navy after the war. As early as September 1914, Tirpitz had written to his wife: `With regard to the great distress after the end of the war, the navy will be lost in my eyes, if it cannot prove some success at least.’ The fact that the High Seas Fleet was unable to break the British blockade of the North Sea further diminished its reputation among the populace, as well as within the political and military establishment. This nightmare of complete failure had haunted the navy’s leadership throughout the war. Despite great efforts it had been unable to turn the tide.

In October 1918, however, danger was in many ways imminent. Both the end of the war, in which the navy had not proven its right of existence yet, as well as a far-reaching reform of the old system, which had been the basis of the navy’s position within the military establishment and within German society, were now in sight. For the navy, defeat would be even more humiliating. In early October, General Ludendorff, Quartermaster-General of the Imperial High Command, had pointed out to a representative of the Supreme Navy Command that the navy would probably be extradited to Britain and that `it would mainly have to pay the bill’ for defeat.

The Supreme Navy Command was by no means willing to accept this fate. Scheer tried to continue unrestricted submarine warfare for as long as possible, but the Emperor finally ordered its suspension on 21 October. More important, as soon as the opportunity arose, Scheer was determined to fight a final battle against the fleet it had challenged for almost two decades-in vain as it seemed so far.

On 30 September 1918, Scheer had already ordered the High Seas Fleet to assemble on Schillig Roads. This was indeed remarkable, for during the war this meant that a sortie was imminent. Several days later, Trotha, the chief of staff of the High Seas Fleet, put forward a memorandum-significantly called `deliberations in a critical hour’. In this memorandum, Trotha suggested that, `From an honorable fleet-action, even though it was a death-struggle in this war, would arise-unless the German people failed-a new future navy.’ Another high-ranking officer and former chief of staff, Captain Michaelis, also proposed a death sortie, though for different reasons. Since defeat was inevitable, he thought that a success at sea might be a means to achieve a change of mood at home and thus help reach a peace that, while bad, still seemed preferable to a total catastrophe.

Scheer immediately accepted the idea of a final sortie by the High Seas Fleet, for this was the only alternative to a humiliating defeat at the hands of its greatest enemy. Moreover, having grown up, like Trotha, in the Tirpitz tradition, Scheer likely shared the latter’s view that only a navy that had gone down fighting bravely could hope to rise again. To disguise its plans, the Supreme Navy Command informed neither the Chancellor nor the Supreme War Lord, the Emperor. Moreover, the final order for Operations Plan No. 19 was passed orally to the newly appointed C-in-C of the High Seas Fleet, Admiral von Hipper, in order to maintain secrecy and avoid interference either from politicians or the Emperor himself, as had happened so often before.

Some historians have argued in recent years that this motive played only a minor role in launching an attack, which made sense neither militarily nor politically. Instead, they assume that the Supreme Navy Command tried to initiate a coup d’état against the Imperial government, which was to be transformed into an institution responsible to parliament in the future. However, there is no proof that this motive was important when the Supreme Navy Command decided upon its last sortie.

The U-boat campaign had failed, even though, in terms of personal courage, the officers and men in the submarine service achieved incredible results. Between 1914 and 1918, 104 U-boats destroyed 2,888 ships of 6,858,380 tons; 96 UB boats 1,456 ships of 2,289,704 tons; and 73 UC boats 2,042 ships of 2,789,910 tons. In addition, the undersea raiders sent to the bottom 10 battleships, 7 armoured cruisers, 2 large and 4 light cruisers, and 21 destroyers. But the cost ran high: 178 boats were lost to the enemy, and with them 4,744 officers and men.

German naval leaders, who as late as August 19 I 8 had been planning amphibious operations against Kronstadt and Petrograd (Operation Schlussstein), proved surprisingly willing to cease the unrestricted submarine warfare. “The Navy”, Scheer’s planners lustily announced, “does not need an armistice.” In fact, a new bold design had entered their heads: the fleet could be hurled against the combined British and American surface units stationed at Rosyth. Admiral v. Hipper concluded that “an honourable fleet engagement, even if it should become a death struggle”, was preferable to an inglorious and inactive end to the High Sea Fleet. Rear-Admiral von Trotha was equally adamant on this matter, arguing that a fleet encounter was needed “in order to go down with honour”. And Admiral Scheer was not the man to stand in the way of such an adventurous undertaking. “It is impossible that the fleet … remains idle. It must be deployed.” Scheer concluded that the “honour and existence of the Navy” demanded use of the fleet, even if “the course of events cannot thereby be significantly altered”.

Hence, for reasons of honour and future naval building (Zukuntsfiotte), it was decided to launch the entire High Sea Fleet against the enemy in a suicide sortie. It is revealing that on 22 October 1918, Levetzow verbally passed on word of the projected sortie to Hipper. The new head of the Army, General Groener, was not brought into these discussions. Nor were the Kaiser or the chancellor informed of the planned operation; despite this, Germany’s admirals at one point considered taking Wilhelm on board for the final naval assault. Scheer, however, simply did not think it “opportune” to inform political leaders of his designs.

On 24 October 1918, the Supreme Navy Command formally adopted Operations Plan No 19 (O-Befehl Nr 19). It called for one destroyer group to be sent to the Flanders coast and another to the mouth of the Thames, while the High Sea Fleet took battle station in the Hoofden, the North Sea between the Netherlands and Great Britain. Twenty-five U-boats were in position to intercept the British and American surface units in the North Sea. The Grand Fleet, the Germans argued, would rush out of its Scottish anchorages in order to attack the two destroyer “baits”, which thereupon would draw the British and American fleets to Terschelling, a Dutch island in the North Sea, where the naval Armageddon would take place.

Execution of Operations Plan No 19 was set for 30 October 1918. With it German naval strategy in desperation returned not only to Tirpitz’s dream of the Entscheidungsschlacht in the southcentral North Sea, “between the Thames and Helgoland”, but also to the conviction of Baudissin, Fischel and Wegener, among others, concerning the need for an offensive in the North Sea in order to force the approaches to the Atlantic Ocean.

Operations Plan No 19, seen in retrospect, was anything but foolproof. In the first place, it is highly doubtful whether the Grand Fleet would have reacted to the advance of the two destroyer flotillas and the submarines in the prescribed manner; British naval leaders had ignored similar German sorties before. Secondly, the expectations which German admirals placed on the U-boats were not sound. By the end of October, only twenty-four submarines were in position and six were heading for their stations. While in the process of heading out to battle stations, seven U-boats were rendered hors de combat owing to mechanical breakdowns, and two were destroyed by the enemy. The weather was also against the submersibles: “Rain and hail showers, hazy, high seas and swell; dismal, stormy November ~weather. No visibility, no possible forward advance, no worthwhile targets for attack could be recognized in the haze.” Finally, the Germans failed to appreciate that apart from Great Britain there was another major sea power involved in the war. In fact, German naval leaders throughout 1917-18 persisted in their claims that United States naval forces as a whole were not worthy of their consideration, and hence paid no attention to the five United States battleships attached to the Grand Fleet, to the three others stationed in Ireland, or to the entire capital-ship strength of thirty-nine units.

Of far greater ultimate effect was the deteriorating internal structure of the Imperial Navy. The naval reorganization of 1I August 1918, which had brought the triumvirate of Scheer, Trotha and Levetzow to the fore, had also caused apprehension concerning planned changes and discharges. Even Admiral v. Hipper noted: “I dread the next few days.” Trotha spoke to Levetzow of “insecurity” and “uneasiness” among commanders and begged for the return of “at least a few leading figures” to the fleet. “We cannot discharge our duties … with only mediocre and bad materiel.” On numerous surface vessels, both captain and first officer had recently been replaced. Nevertheless, when Levetzow asked Trotha on 16 October if he believed that naval personnel could be relied upon for a major sea battle, Trotha “answered without reservation in the affirmative”. This miscalculation was to prove decisive within a fortnight.

The High Sea Fleet, according to Operations Plan No I 9, was to assemble in Schillig Roads on the afternoon of 29 October. Two days before, the crews had already appeared anxious and excited. News had leaked out, especially from Hipper’s eager staff, that a major battle with the British was in the offing. Men in both Kiel and Wilhelmshaven nervously spread the word of a “suicide sortie” planned by the executive officers to save their “honour” at the eleventh hour – a notion not without ample basis.

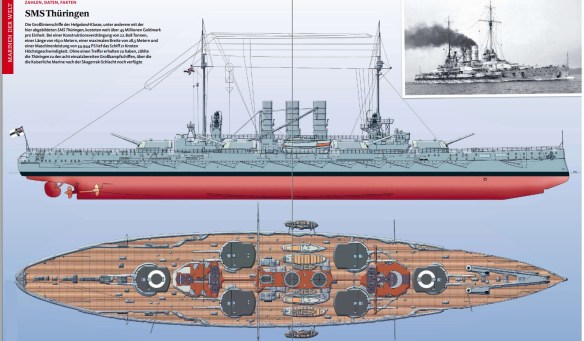

By the 29th, ratings from the battle-cruisers Derfflinger and Von der Tann failed to return to their posts from shore leave. Sailors assembled to demand peace and to cheer Woodrow Wilson. Insubordination quickly spread to the Third Squadron battleships Kaiserin, Konig, Kronprinz Wilhelm, and Markgraf as well as to Thuringen and Helgoland in the First Squadron. The Baden’s crew also seemed on the verge of revolt, and the battle-cruisers Moltke and Seydlitz were rendered inoperative because of rebellious sailors, as were the light cruisers Pillau, Regensburg and Strassburg. Only the men on the torpedo-boats and the U-boats remained calm and loyal to their officers.

The disturbances in the fleet on 29 October caught naval leaders off-guard and unprepared. Hipper initially cancelled sailing orders late in the evening of the 29th, but reactivated them later as he was unaware of the extent of the rebellion. Trotha at first agreed that the revolt was only temporary and that discipline could be restored shortly. But when disorder spread on 30 October to Friedrich der Grosse and Konig Albert, the game was up. Hipper now realized that Operations Plan No 19 had been stillborn. “What terrible days lie behind me. I had really not thought that I would return [from battle], and under what circumstances do I return now. Our men have rebelled.”

One of Hipper’s last acts as Chief of the High Sea Fleet was to disperse the rebellious ships, sending the First Squadron to the Elbe, the Third to Kiel, where it surprised an utterly unprepared Admiral Souchon, and the Fourth to Wilhelmshaven. He could hardly have made a more grievous miscalculation. In the various ports along both Baltic and North Sea shores, the sailors incited local uprisings and there found mostly hospitable receptions. Sea battalion soldiers refused to fire on them. Executive officers did not oppose them. A mere four Seeoffiziere were wounded in their efforts on behalf of the Kaiser.

Admiral von Trotha quickly informed Scheer, on 2 November, that the rebellion was a “Bolshevist movement”, but one that was directed against the government rather than against the officer corps. One day later, Trotha met with Levetzow to co-ordinate their stories concerning Operations Plan No 19. It was placed entirely in a defensive light, with stress placed primarily upon the submarines in the North Sea; the anticipated British advance from the north was sold as an attack on the German fatherland. Trotha even visited the offices of the Social Democratic newspaper Vorwarts to make quite certain that this official line was properly played up. Not yet knowing of the official line, the State Secretary of the Navy Office, Vice-Admiral von Mann, told the rebellious sailors of the Third Squadron that the sortie against the British had been designed to bring the U-boats home safely.

Admiral Scheer was not quite as inventive. He placed the entire blame for the failure of the operation upon the Social Democrats, and specifically upon the government’s inability in the autumn of 1917 to suppress the USPD. Scheer wrote after the war: “It still appears almost incomprehensible to me: this reversal from certain victory to complete collapse, and [it is] especially degrading that the revolution was planned without haste, and in thorough detail, right under our eyes.” At least the Navy’s liaison officer at Army headquarters, Lieutenant-Commander von Weizsacker, grasped the meaning of the events in the fleet: “We do not even know the state of mind within the naval hierarchy; this has been demonstrated during the planned assault.”

The aftershock of the mutiny continued a long time. Even many months after the revolution and as far away as Scapa Flow, many sailors still hated their officers. For example, on board the battleship Friedrich der Große, the former fleet flagship, men roller-skated on top of officers’ cabins day and night in order to break their nerves. Against this background, it is hardly astonishing that the great majority of the old officers corps regarded the mutiny and the revolution as a stain on the navy’s shield.

In the eyes of the officer corps, the mutineers and their-alleged – political leaders were nothing but `November criminals’, who had stabbed a proud and almost-victorious army and navy in the back. As soon as possible, they were to take revenge for this infamous crime. As early as October 1918, a high-ranking naval officer had written to the chief of staff of the Supreme Navy Command: `Unfortunately, we have been unable to keep the shield shining, which we took over from our ancestors stainless; our sons will have to wash off this stain. They shall work and hate.’ Subsequently, in 1919-20 naval officers conspired against the democratic Weimar Republic. They only failed because the trade unions proclaimed a general strike. Nevertheless, in this respect, the brutality of Scheer’s former chief of staff, Admiral von Levetzow, when fighting demonstrating workers in Kiel in 1920, was only an example of worse developments to come.

Not surprisingly, the idea of a future revenge also included acting against its former wartime enemies. In 1936, when Admiral Beatty, the C-in-C of Britain’s Grand Fleet in the final years of the war, died, Grand-Admiral Raeder refused to comply with the latter’s last wish that the C-in-C of the German Navy take part in his funeral. Thus, Raeder finally made clear that he still had not forgiven Beatty for the order he had signaled to the vessels of the Grand Fleet when the High Seas Fleet was approaching the Firth of Forth in November 1918, `that the enemy was a despicable beast’.

Not surprisingly, when Hitler came to power in 1933, the navy firmly supported his regime. Although he reckoned with a much longer period of peace in order to build up a powerful navy, Raeder left no doubt that the navy fully endorsed Hitler’s plan of establishing German hegemony on the continent and of challenging Britain. More important, still suffering from the traumatic events of November 1918, the navy tried to be more loyal than either the army or the air force. In his memoirs, Raeder admitted that `every officer had sworn a silent oath that there would be no November 1918 in the Navy again’. This refusal to acknowledge either their own shortcomings or the structural problems of Wilhelmine society blinded naval officers to the prerequisites of a modern democratic society. In 1945, the wheel finally came full circle: there could be no doubt that the navy’s leadership also bore responsibility for this second catastrophe in German history in the twentieth century.