An increasingly powerful and efficient Allied intelligence, from the breaking of the Enigma cipher and also the highly sophisticated use of Huff-Duff, or HFDF, to pinpoint the position of U-boats far out in the ocean, and apparently safe from air or surface attack.

One example from June 1942 shows how effective this was. The crew of the type IXC U-158 had sunk thirteen ship in the Gulf of Mexico and off Bermuda. They had boarded and scuttled their final victim, a 4,000-ton freighter, after using all their torpedoes. The skipper, Erich Rostin, reported to U-Boat headquarters on 30 June, but his brief signal was picked up by several different direction-finding stations, including one on Bermuda, to give an accurate position, Bermuda-based US Navy Patrol Squadron 74, equipped with Martin Mariner flying boats, ordered one to the reported position.

After a 50-mile flight, the crew found U-158 on the surface with sailors sun bathing on deck, In waters so close to Allied bases, they paid the price for this criminal negligence within minutes, Before the crew could react, the Mariner dropped two anti-submarine bombs, but not close enough to the submarine to inflict serious damage, The plane turned and delivered another attack, dropping two Mark XVIl depth charges with shallow settings on the now rapidly diving submarine, One seemed to jam in the conning tower structure, and when the U-boat finally submerged, it detonated with fatal results, U-158 was lost with all her crew, in a fast and clinical operation that would become increasingly routine.

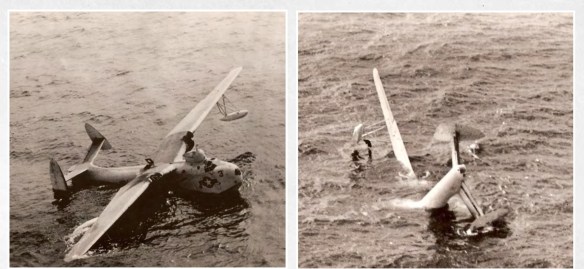

A Mariner meets its watery grave. In 1944 this aircraft was on a test flight when it suffered an engine fire and the pilot was forced to make an emergency landing. It hit the water so hard that both engines were ripped off, but the integrity of the strong PBM hull remained. The crew evacuated the aircraft safely and the stricken machine continued to float for an hour and a half before finally succumbing to its inevitable fate.

The Martin Mariner didn’t get a lot of press. Various sources credits ASW Mariners with 10 U-boat kills in the North Atlantic; other runs that up to 12. Martin Mariners were nicknamed “flying gas tanks” because they tended to leak fumes.

Martin had a history of producing flying boats, and in 1937 the company began work on a design to replace the Consolidated Catalina in US Navy service. Martin’s Model 162, naval designation XPBM-1 (Experimental Patrol Bomber Martin 1), had a deep hull and shoulder-mounted gull wings, a flat twin-fin tail and inward-retracting wing floats. The gull wing design was used to produce the greatest possible distance between the engines and sea water. A less than half-scale single-seat version was produced to test the aerodynamics of the design, and its success led to the first flight of the full-scale prototype XPBM-1 in 1939.

The XPBM-1 prototype first flew in February 1939 and test flights called for a redesign of the tail, which resulted in the dihedral configuration that matched the angle of the main wings. The aircraft had been ordered before the test-flight, so the first production model, the PBM-1, appeared quite quickly in October 1940 with service deliveries being complete by April 1941. By now the type was named Mariner. The PBM-1 had a crew of seven and was armed with five 12.7mm/0.5in Browning machine-guns. One gun was mounted in a flexible position in the tail, one was fitted in a flexible mount on each side of the rear fuselage, another was fitted in a rear dorsal turret and one was fitted in a nose turret. In addition, the PBM-1 could carry up to 908kg/2000lb of bombs or depth charges in bomb bays that were, unusually, fitted in the engine nacelles. The doors of the bomb bays looked like those of landing gear, but the Mariner was not amphibian at this stage.

In late 1940 the US Navy ordered 379 improved Model 162Bs or PBM-3s, although around twice that number were actually produced. This order alone required the US government-aided construction of a new Martin plant in Maryland. The -3 differed from the -1 mainly by the use of uprated Pratt & Whitney 1700hp R-2600-12 engines, larger fixed wing floats and larger bomb bays housed in enlarged nacelles. Nose and dorsal turrets were powered on this version. Early PBM-3s had three-bladed propellers, but production soon included four-bladed propellers.

The PBM-3C, rolled out in late 1942, was the next major version, with 274 built. It had better armour protection for the crew, twin gun front and dorsal turrets, an improved tail turret still with a single gun, and air-to-surface-vessel radar. In addition, many PBM-3Cs were fitted with an underwing searchlight in the field.

US Navy Mariners saw extensive use in the Pacific, guarding the Atlantic western approaches and defending the Panama Canal. It was concluded that most Mariners were not likely to encounter fighter opposition, so much of the defensive armament was deleted – once the guns, turrets and ammunition were removed, the weight saving resulted in a 25 per cent increase in the range of the lighter PBM-3S anti-submarine version. However, the nose guns were retained for offensive fire against U-boats and other surface targets. Despite this development, a more heavily armed and armoured version, the PBM-3D, was produced by re-engining some 3Cs. Larger non-retractable floats and self-sealing fuel tanks were also a feature of this version.

Deliveries of the more powerfully engined PBM-5 began in August 1944, and 589 were delivered before production ceased at the end of the war. With the PBM-5A amphibian version (of which 40 were built), the Mariner finally acquired a tricycle landing gear. The Mariner continued to serve with the US Navy and US Coast Guard into the early 1950s, and over 500 were in service at the time of the Korean War. The USCG retired its last Mariner in 1958.

The first PBM-1s entered service with Patrol Squadron Fifty-Five (VP-55) of the US Navy on 1 September 1940. Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, PBMs were used on anti-submarine patrols, sinking their first German U-boat, U-158, on 30 June 1942. PBMs were responsible, wholly or in part, for sinking a total of 10 U-boats during the conflict. PBMs were also heavily used in the Pacific War, operating from bases at Saipan, Okinawa, Iwo Jima and the South West Pacific.

Patrol Squadron 16 was formed in December 1943 at Harvey Point, North Carolina. The PBM-3D Martin Mariner was a larger but less reliable cousin to the Consolidated PBY Catalina that was first developed in the early 1930s. The PBMs, unlike the PBYs, did not become operational until the early 1940s and suffered a number of problems common to a new type of aircraft. Besides design and structural issues, the underpowered Wright R-2600-22 engines were a source of constant worry to those who flew in the Mariner. Engine failures were common, and few PBMs could boast making it back to base on just one. The failure of both often resulted in the loss of all aboard. The one thing the Catalina and the Mariner had in common, however, was that they were both slow, with maximum speeds of around 200 miles per hour and a normal cruising speed of well under that. Put another way, they were both meat on the table for any fighter plane of that era.

Mariners continued in service with the US Navy following the end of World War 2. The PBM- 5A, produced after the war, saw service during the Korean conflict.

Martin PBM-3D Mariner

First flight: February 18,1939 (XPBM-1)

Power: Two Wright 1900hp R-2600-22 Cyclone radial piston engines

Armament: Eight 12.7mm/0.5in machine-guns in nose, dorsal, waist and tail positions; up to 3632kg/8000lb of bombs or depth charges

Size: Wingspan – 35.97m/118ft

Length – 24.33m/79ft 10in

Height – 8.38m/27ft 6in

Wing area -130.8m2/1408sq ft

Weights: Empty – 15,061 kg/33,1751b

Maximum take-off – 26,332kg/58,000lb

Performance: Maximum speed – 340kph/211 mph

Ceiling – 6035m/19,800ft Range – 3605km/2240 miles

Climb – 244m/800ft per minute