Pursuing their pre-war policies of attempting to subjugate an enemy through bombing, the British and Americans were by 1942 in possession of a rapidly- expanding fleet of several makes of four-engine bombers capable of carrying, in the case of the British Lancaster B1 for example, 12 000 lb a distance of 1730 miles, and in the case of the American Boeing B 17F, 6000 lb for 1300 miles. The major performance difference between the respective types lay in their ceilings of 24 500 ft and 37 500 ft, and their operating mode. The British intended mainly to operate in a continuous stream under cover of darkness; the Americans to fight their way through by day in packed formations protected by batteries of heavy machine- guns escorted part of the way by short-range fighters. Each method posed the German defenders with conflicting defensive problems, while their attackers faced the perennial difficulties of finding and hitting targets. Remarkable in technology as the contending aircraft and anti-aircraft guns were; well as their crews might be trained; skilful as the directors of operations would become in deploying several hundred machines at once over strategically important industrial targets, centres of communication and population, success in attack and defence depended in the final analysis upon a few electronic devices. Without them the bombers would rarely hit their targets; the fighters could not find the bombers; and the bombers could not counter a growing array of defensive measures.

It is possible to outline only a few complex moves here, starting with the night in March 1942 when 80 Gee-fitted bombers started fires in the Ruhr, to which another 270 bombers homed with devastating effect. This was more impressive than all previous raids, for a study of air photographs, linked to operational analysis, had indicated that only 30% of night-flying crews were dropping their bombs within five miles of the intended target. It was all the more successful because the Germans, who used Lorenz beams, allowed themselves to be deluded by subsidiary Lorenz transmissions. This shielded Gee from jamming for nearly a year, by which time mitigating measures (such as changing the Gee frequency) had been prepared.

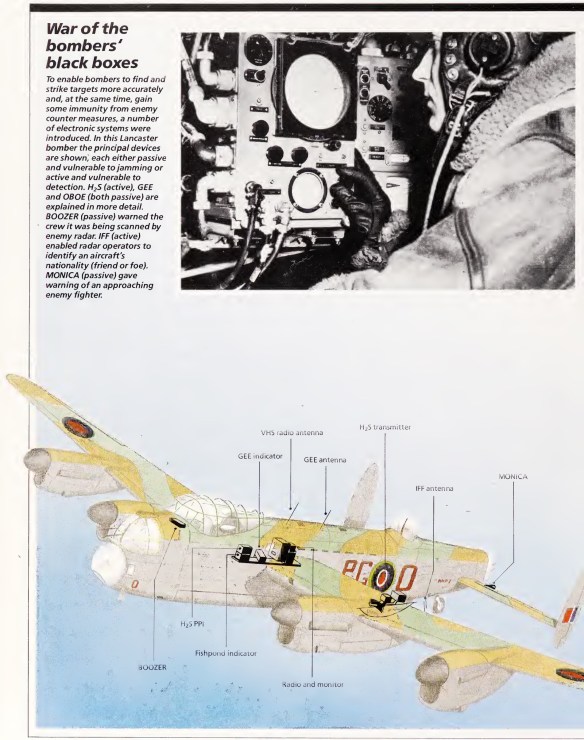

Complementary to Gee was Oboe, a bomb-aiming radio aid which emitted a tone to the aircraft and instructed it exactly when to release its bombs to within 20 yards of the target. Fitted into another triumph of technology (the 400-mph, twin-engine Mosquito light bomber of wooden construction), Oboe spearheaded the technique of dropping special pyrotechnic candle `marker bombs’ as a guide for fire- raisers which, in turn, led the stream of bombers to the target. But because of screening caused by the Earth’s curvature, Oboe was limited in range by the maximum altitude of the Mosquito at 37 000 ft. It was a downwards-scanning radar device called H2S (because initially its sceptical designers thought its prospects stank) which gave accurate navigation to unlimited distances by displaying on the CRT a picture of the terrain below which could be related to a chart. Oboe came into service in December 1942; H2S two months later. Along with Gee they enabled Allied bombers to find their targets unerringly. Moreover, Oboe escaped jamming because German scientists did not relate its signal to a bombing aid, and H2S could not be jammed. The outcome was the delivery of vast tonnages of high explosive in bombs which, in due course, weighed as much as 10 tons. Their purpose was to pulverize factories, penetrate 15-ft-thick concrete U-boat shelters and sink pin-point targets, such as the 42 000-ton battleship Tirpitz, which was achieved with two 12 000-lb bomb hits and several near-misses. In addition, fire-bombs could engulf a city in flames to create a new phenomenon, the firestorm, caused by air sucked through burning buildings with blast-furnace force. But just as this vast new technology of electronics, aerodynamics and metallurgy was invented for massive forces of destruction, defences were strengthened by parallel efforts every bit as impressive.

Improved ground radar sought to establish the position of the attackers prior to engagement by radar- directed guns and interception by radar-equipped fighters. Commanders and controllers connived with scientists to devise better techniques with existing equipment while calling for still more sophisticated devices. The battle swayed to and fro as one side or the other obtained some transitory advantage. For example, the employment of `Window’ – clouds of metallic chaff cut to a precise length to give false echoes on German radar – created chaos among the German air defence systems when first used on the night of 24th July 1942 during a major attack on Hamburg. Only 12 out of 741 bombers were lost. But the Germans had successes too. When 367 US Air Force B 17s attacked the Messerschmitt factory at Regensburg and the ball-bearing factory at Schweinfurt in daylight on 17th August 1943, they lost 59 aircraft and had 55 bombers damaged beyond repair as the result of superbly-directed fighter attacks. And that same night when 597 RAF bombers attacked the rocket weapons experimental establishment at Peenemünde, the night fighters, despite interference from Window, brought down or severely damaged another 72 machines. In terms of technical warfare, however, Peenemünde had a very special significance not simply as the first instance in which a Master Bomber aircraft directed the bombers by markers and radio instructions against pin-point objects within the target area; nor because of specific aiming, with some success, against the living quarters of the scientists and technologists; but chiefly because this was the first shot in the anti-rocket missile war.

Devastating attacks on cities, such as those on Hamburg in the summer of 1943 and on Berlin a few months later, seemed to Speer to have German morale reeling. Speer feared too that persistent attacks on key industrial targets might cause economic collapse. But invariably the Allies, from lack of intelligence or failure to hit the target or from severe losses, called off campaigns when Speer thought they were on the verge of success. On the other hand, there were periods in which the German defences inflicted terrible execution on Allied bombers, such as the end of 1943 and early 1944. The classic debacles were over Schweinfurt on 14th October, when 60 B 17s were lost and 138 severely damaged; or the night of 30th March 1944 when 294 German fighters shot down 94 RAF bombers out of 794 during an abortive attack on Nürnberg. Such reverses led to deep-penetration raids being called off until new methods could be devised. Both by night and by day the answer lay with the introduction of long-range fighter escorts fitted with drop fuel tanks, and by still more sophisticated Electronic Counter Measures (ECM) allied to deception measures and the jamming of enemy airborne intercept radar. It was struggle with no reprieve for errors and omissions. For example, the habit of British bomber crews to switch on their H2S sets throughout the flight presented German fighter controllers with ECM-free plots until, after a year of fatal consequences, the Allies realized what was happening. Or the German failure to concentrate on jet fighters which might well have won air superiority and put an end to daylight bombing.

Persistent heavy losses weighed heavily against air forces. There had to come a point at which replacement of machines and crew became impossible or morale was severely shaken. Had punitive losses been inflicted upon the 10 000 or more aircraft committed to support of the invasion of Europe in June 1944, airborne troops might not have survived; and air support for the rest of the amphibious force might have been so impaired that the Allied cause would have suffered even stiffer resistance from the Germans than was actually the case. As it was, Allied air superiority gave their surface forces a free hand to bear down overwhelmingly upon the Germans at any time.

List of World War II electronic warfare equipment

- Abdullah – British radar homing system for attacking German radar sites – carried by rocket-armed Typhoons for Operation Overlord.

- AI (Airborne Interception) – Night fighter radar.

- Airborne Cigar (A.B.C.) – ARI TR3549 radar jammer carried by 101 Sqn Lancasters based at Ludford Magna, and from March 1945 by 462 Sqn RAAF, operating from RAF Foulsham. These aircraft carried an 8th crew member to monitor and then jam Lichtenstein radar of German night fighters.

- Airborne Grocer – British 50 cm radar jammer against early model (B/C and C-1) UHF band Lichtenstein – see also Grocer/Ground Grocer.

- Alberich – German anti-ASDIC rubber coating for U-boat hulls – tested on U-67.

- ASDIC – British sonar system used for hunting U-boats.

- Aspidistra – used for Corona, q.v.

- Aspirin – British Knickebein jammer.

- ASH – Air to Surface H or AI Mk XV (U.S AN/APS-4). centimetric airborne air-air radar derived from ASV operating at 3 cm wavelength at a frequency of 10 GHz. Used by 100 Group Mosquitos; postwar in the Sea Hornet N.F. Mark 21.

- ASV – Air to Surface Vessel radar. A 1.5 metre radar that could detect surfaced submarines at up to 36 miles.

- Beam Approach Beacon System (BABS) ARI TR3567 – British blind-landing system using the Eureka beacon.

- Benjamin – British Y-Gerät jammer – see also Domino.

- Berlin, German Funkgerät or FuG 240 night fighter radar, introduced April 1945, centimetric (microwave) frequency radar (9 cm/3 GHz).

- Boozer – ARI R1618 fighter radar early warning device fitted to British bombers.

- Bremenanlage – FuG 244/245, German omnidirectional airborne search (AEW-capable) radar (experimental only).

- Bromide – British X-Gerät jammer.

- Bumerang – German codename for Oboe-guided Mosquitoes when detected on Flammen radar – ‘boomerang’, from curved track flown

- BUPS – Beacon Ultra Portable S-band, AN/UPN-1.

- Carpet – 100 Group W/T (morse radio) jammer – from TRE; US version built as AN/APT-2.

- Cigar (later “Ground Cigar”) – earlier ground-based version of Airborne Cigar.

- Corona – 100 Group radio transmissions using German-speaking personnel, and later WAAFs, for spoof controlling of German night fighters to confuse German counter-attacks.

- Chaff – shorter-length Window for use against possible German development of microwave radar, e.g. Berlin.

- Chain Home radar – British land based early warning radar used during the Battle of Britain – from TRE.

- Düppel – German radar countermeasure called chaff in the US or Window in Britain.

- Darky – British backup homing system: the pilot could be talked back to his home base by voice radio on 6.440 MHz

- Diver – Integrated RAF and Royal Observer Corps system for intercepting German V1 flying bombs in flight.

- Domino – British Y-Gerät jammer – see also Benjamin.

- Egerland – German fire-control radar-linked Marbach and Kulmbach systems, only two built by 1945

- Egon – German-devised bomb-targeting system using the Erstling IFF system and two Freya radar ground stations for bomb-aiming.

- Eureka – portable homing beacon system – ground transmitter – see also Rebecca.

- Filbert – 29-foot-long (8.8 m) naval barrage balloon fitted with internal 9 feet (2.7 m) radar reflector, for Operation Glimmer and Operation Taxable.

- Flammen – German plotting system for detecting Oboe-equipped Pathfinder Mosquitos.

- Funk-Gerät — German prefix-phrase for nearly all their military avionics system designations, translated as “radio equipment” and abbreviated as FuG.

- Fishpond – British fighter warning radar add-on to H2S, fitted early 1944 to some bombers.

- Flensburg – FuG 227, German radar detector fitted to night fighters to detect the British Monica tail warning radar transmissions.

- Freya – German ground based air search radar.

- G-H – British radio navigation system used for blind bombing, from TRE.

- GEE – British radio navigation system forerunner of LORAN, from TRE.

- Grocer (later “Ground Grocer”) – ground-based version of Airborne Grocer.

- Gufo radar – Italian naval search radar (official designation EC3/ter) employed by the Regia Marina. Operational from 1942 to 1943.

- H.F. D/F (High Frequency Direction Finding) – provided a radio position fix for the RAF up to 100 miles from the transmitters in Britain. The system was based on voice communications, and was used for aircraft to find their home bases. With the development of GEE, its primary function ceased but it remained in use until the end of the war as a backup system and a communications system between aircraft and their bases.

- H2S – British ground mapping radar to see target at night and through cloud cover – from TRE.

- H2X – American 10 GHz ground mapping radar, higher frequency development of British H2S. Equivalent to S-band H2S Mark III.

- High Tea – British sonobuoy used by RAF Coastal Command in 1944.

- Himmelbett – German controlled night fighter method.

- Hohentwiel – FuG 200, German UHF airborne radar optimized for maritime patrol use, named for Hohentwiel, an extinct volcano in south-western Germany.

- Hookah – ARI R1625/R1668 British jammer-homer operating on 490 MHz (to jam the Germans’ FuG 202 and 212 AI radars) and 530–600Mhz.

- Huff-Duff – Allied HF/DF High Frequency Direction Finding.

- Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) – means of identifying possible enemy aircraft detected on Chain Home early warning system using transponder fitted in RAF aircraft – from TRE.

- Jay beams – were introduced partly as a deception to help to confuse the Germans over the use of GEE. It was nevertheless just as useful as a homing beacon. A number of transmitters, from Lossiemouth to Manston in Kent transmitted on slightly different frequencies transmitted a narrow beam across the North Sea using a S.B.A. (Standard Beam Approach) transmitter, receivers for-which were fitted to all British bombers and could be received over a range of 350 miles at 10,000 feet. Once a bomber found a beam it could fly down it back to Britain. In late 1943, all but two beams were closed with the final two shutting down towards the end of 1944 because GEE could do the job better and their use to deceive the Germans was by now redundant.

- Jostle – 2.5kW airborne jamming transmitter carried in sealed bomb bays of 100 Group Fortresses, from TRE.

- Kehl – series of German aircraft-mounted, joystick interface radio control transmitter sets, designated FuG 203, for use in MCLOS operation of Hs 293 and Fritz X weapons, its signals were received by the FuG 230 Straßburg units in the ordnance. Named after Strasbourg, France and Kehl, one of its German suburbs.

- Kettenhund – German jammer of the Eureka beacon.

- Knickebein – German dual beam radio navigation aid, used early 1940.

- Kulmbach – German targeting radar based on Marbach – linked with Marbach to form Egerland.

- Lichtenstein – German UHF (B/C and C-1 versions), later VHF (SN-2 version) night fighter radar, introduced 1941/1942, with both versions compromised after July 1944.

- Lorenz – German blind-landing aid.

- LORAN – American navigation aid.

- Lucero – British homing system carried by some Mosquitos for homing-in on Kettenhund jammers (Eureka jammer), from TRE.

- Mandrel – jammer for Freya and Würzburg radar used by 100 Group, from TRE. US version built as AN/APT-3.

- Marbach – German microwave ground-based search radar, c. 1945.

- Metox – metre-wavelength ASV radar detector fitted to German submarines

- Meacon – Masking BEACON – British long wave jamming station – see Meaconing.

- M.F. D/F (Medium Frequency Direction Finding) – provided a radio position fix for the RAF up to 230 miles from the transmitters in Britain. The system was based on voice communications.

- Mickey — American nickname for their H2X 10 GHz band blind bombing radar

- Monica tail warning radar – fixed rearward-pointing radar fitted to British bombers to warn of attacking fighters.

- Moonshine – ARI TR1427 British airborne spoofer/jammer installed in 20 modified Boulton Paul Defiants (No. 515 Squadron RAF) to defeat Freya, from TRE.

- Naxos – FuG 350, German H2S detection and homing device, not capable of detecting the Americans’ similar, higher frequency (10 GHz) H2X radar.

- Neptun – FuG 216, -217 & -218, German high-VHF-band (125 to 187 MHz) night fighter AI radar, introduced mid/late 1944, generally used the Hirschgeweih antenna setup of Lichtenstein VHF-band radar sets with shorter dipole elements, as a replacement for the compromised Lichtenstein SN-2 90 MHz AI equipment.

- Newhaven – target marking blind using H2S then with visual backup marking, from Newhaven, East Sussex.

- Oboe – British twin beam navigation system, similar to Knickebein but pulse-based.

- Parramatta – target marking by blind dropped ground markers – prefixed with ‘musical’ when Oboe-guided – from Parramatta, New South Wales.

- Perfectos – device carried by night fighting Mosquitos for homing-in on German nightfighter radar transmissions and triggering IFF.

- Ping-Pong – ground-based direction finder accurate to a quarter degree, three of them could be used to make a plotting system for triangulating German radar site positions, allowing them to be attacked and disabled immediately prior to Overlord.

- Piperack – airborne jamming transmitter carried by a lead aircraft that produced a cone of jamming behind it, within which the following bomber stream could shelter, carried by 100 Group Fortresses and Liberators, from TRE.

- Pip-squeak – “Huff-Duff” IFF system used by the RAF in the Battle of Britain, to track fighter squadrons in the air.

- Rebecca – portable radio beacon system – airborne receiver – see also Eureka

- Roderich – German 4W radar jammer for use against H2S.

- Rope – extended-length Window suspended from a small parachute; dropped by aircraft of 218 and 617 Squadrons to deceive German Seetakt coastal radar during Operation Glimmer and Operation Taxable.

- Seetakt – a shipborne radar developed in the 1930s and used by Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine, later improved into Freya air search radar.

- Serrate – British radar detection and homing device, used by night fighters to track down German night fighters with early UHF-band versions of Lichtenstein.

- Shiver – first attempts at jamming Würzburg using ground transmissions.

- Tinsel – British technique of transmitting amplified engine noise on German night fighter voice frequencies to hinder them.

- Village Inn – British radar-aimed Automatic Gun-Laying Turret (AGLT) fitted to some Lancasters in 1944 – from TRE.

- Wanganui – target marking by blind-dropped sky markers when ground concealed by cloud – prefixed with ‘musical’ when Oboe-guided – from Wanganui, New Zealand.

- Window – strips of aluminium foil dropped to flood German radar with false echoes – from TRE.

- Würzburg – German ground based air search radar.

- X-Gerät – German multiple beam guided blind bombing system

- Y-Gerät – German single beam guided blind bombing system, also known as Wotan.