The fortress resisted five Imperial sieges in the Thirty Years’ War, under the command of Konrad Widerholt between 1634 and 1648. The effect was that Württemberg remained Protestant, while most of the surrounding areas returned to catholicism in the Counterreformation.

The mountaintop fortress of Hohentweil under attack in October 1641.

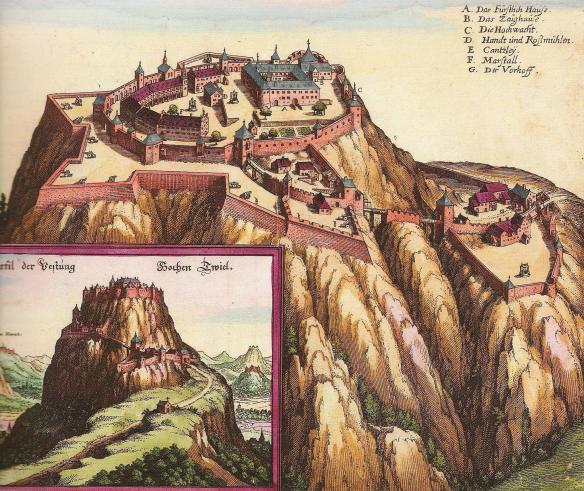

1643 illustration of Festung Hohentwiel (Hohentwiel Fortress), near modern Singen, Germany.

The only feasible way from Alsace for an army is around the southern end of the Black Forest where the route divided. One branch ran north east to the upper reaches of the Danube around the Württemberg enclave of Tuttlingen and thence to Bavaria. This route was overlooked by the duke’s impregnable castle of Hohentwiel perched on an extinct volcano 263 metres above the surrounding plain. The other branch ran east through the towns of Überlingen, Lindau and Radolfzell along the northern shore of Lake Constance to the Bregenzer Klause, the pass giving access to the Tirol and Valtellina. The area between the lake, the Danube and the Bavarian frontier was studded with walled imperial cities, notably Ravensburg, Kempten, Memmingen, Ulm and Augsburg. The emperor was rarely able to devote significant resources to defending these positions, despite a strategic importance that grew with French intervention in 1635. Defence was left largely to local militia, especially in Villingen and the imperial city of Rottweil which guarded the back door from Württemberg through the Black Forest to Breisach.

Sweden Loses Southern Germany

Against this the Habsburg loss of 2,000 seemed slight and enabled them to claim a major triumph. Following a long succession of defeats, Nördlingen appeared to be vindication for Wallenstein’s murder and cemented the influence of Gallas and Piccolomini by associating them with victory. As at Breitenfeld, the scale was magnified by the demoralization of the enemy army. News of the defeat reached Frankfurt on 12 September along with a flood of refugees. The remaining Heilbronn delegates fled the next day. Oxenstierna tried to improvise a new line of defence along the Main to contain the defeat to the south. No one cooperated. Johann Georg failed to launch the requested diversionary attack against Bohemia, while Duke Georg refused to move south to hold the middle section of the river. Wilhelm of Weimar abandoned Franconia and fell back with 4,000 men to his base at Erfurt, exposing the upper Main to Piccolomini and Isolano who approached with 13,000 troops from Nördlingen and north-west Bohemia. Piccolomini took Schweinfurt, while Isolano destroyed the Suhl arms workshops that had supplied most of the Swedes’ small arms and munitions since 1631. Isolano and 6,000 Croats then swept down the Main in November, rampaging into the Hessian possession of Hersfeld.

The main imperial army moved west, bypassing Ulm to enter Stuttgart on 19 September. Duke Eberhard III fled to Switzerland and the last Württemberg fort surrendered in November. Only the isolated Hohentwiel on the upper Danube held out. While the Imperialists made themselves at home, the Spanish continued westwards and the Bavarians, now under the command of Werth, captured Heidelberg on 19 November, though its castle remained defiant. Riding ahead, Werth’s cavalry harried the remnants of Bernhard’s army as it fled to Frankfurt. The commanders of Sweden’s Rhine army refused to join him, on the ground this would spread demoralization to their own troops. Birkenfeld abandoned Heilbronn and retreated to the Kehl bridgehead opposite Strasbourg. His hopes of replacing Bernhard were dashed by Oxenstierna, who felt there was no realistic alternative to the defeated general. The death of Count Salm-Kyrburg to plague on 16 October enabled Bernhard to incorporate the former Alsatian units into his command.

Leaving Werth and Duke Charles to complete the conquest of the Lower Palatinate, Fernando continued his march down the Rhine, crossing at Cologne on 16 October to reach Brussels nineteen days later. Meanwhile, Philipp Count Mansfeld collected the Westphalians at Andernach, allegedly accompanied by a hundred coach-loads of Catholic lords and clergy eager to recover their property. As Philipp marched south, it looked as if Bernhard would be crushed between his hammer and Gallas’s anvil.

The situation mirrored that of 1631, only this time Protestant areas were the ones affected as government collapsed in the wake of the headlong flight of Sweden’s German collaborators. Suffering was also more general because the plague hindered the harvest, causing widespread hardship. There were signs that Emperor Ferdinand had learned the lessons of 1629 as efforts were made to restrain over-zealous Catholics. He intervened to stop Bishop Hatzfeldt punishing the Franconian knights for collaborating with the Swedes and the Jesuits were refused permission to take over Württemberg’s university at Tübingen. Political considerations undoubtedly influenced this, since Vienna did not want to jeopardize promising negotiations with Saxony. Archduke Ferdinand’s presence was another moderating factor. However, it often proved impossible to stop officers and administrators exploiting the situation, either to enrich themselves or to find cash for the perennially underpaid imperial army. Catholic government resumed relatively quickly in Würzburg despite the Swedish garrison holding out on the Marienberg and in Königshofen until January and December 1635 respectively.

Oxenstierna worked feverishly to salvage what he could of the situation, reconvening the Heilbronn League congress at Worms on 2 December. Though some members were willing to fight on, most sought a way out through Saxon mediation. Saxon and Darmstadt envoys agreed draft peace terms, known as the Pirna Note, on 24 November. Oxenstierna tried to stem desertion by publishing what he could discover of the terms, notably the suggestion of 1627 as a new normative year that would secure many of the Catholic gains.

Partisan Leaders

The horrendous losses of the 1638 Rhine campaign were a major factor behind this decline. Bernhard of Weimar was determined to achieve the objective set the year before and establish a firm foothold for France east of the river. This time he prepared thoroughly. Since he had wintered in Mömpelgard and the bishopric of Basel, he was already close to the stretch of the Rhine along the Swiss frontier to Lake Constance. This route offered an alternative to the previous year’s attempt to punch directly across the Black Forest. Though he had been joined in person by Rohan, who had escaped from the Valtellina, he still had few troops. Savelli’s Imperialists held Rheinfelden with 500 men, with other garrisons in Waldshut, Freiburg and Philippsburg and Reinach’s regiment in Breisach. These posts would have to be taken if the river was to be secured. He also needed a base beyond the Black Forest to tap the richer resources of Württemberg and the Danube valley.

Fortunately, Bernhard had an excellent spy network and knew how weak his opponents were. He also had the services of Colonel Erlach, a veteran of Dutch service who had been wounded at White Mountain and subsequently served Mansfeld and Sweden until 1627. Since then he had commanded the militia of his homeland, the Protestant canton of Bern. He joined Bernhard’s army in September 1637, although he did not leave Bernese service until the following May. His contacts with the canton’s patriciate ensured a good flow of supplies to Bernhard’s army.

Erlach also opened negotiations with Major Widerhold, a Hessian who was the Württemberg militia’s drill instructor and commandant of the Hohentwiel, the duchy’s only fortress still holding out against the emperor. Though he has now faded from the local popular consciousness, Widerhold occupied a prominent place in Swabian patriotic folklore into the twentieth century. He exemplifies the partisan leaders who played an increasingly important role as the rapid escalation of the conflict left numerous isolated garrisons scattered across the Empire. These sustained themselves by raiding and acted as potential bases should friendly forces return to their area. The Swedes in Benfeld, Ruischenberg’s Imperialists in Wolfenbüttel and Ramsay’s Bernhardines in Hanau are three examples encountered already. Others included the Hessians in Lippstadt under the Huguenot refugee Baron St André and his subordinate, Jacques Mercier from Mömpelgard, known as Little Jacob, who rose through the ranks of Hungarian, Bohemian, Russian and Dutch service. Both were contemporary celebrities incorporated by Grimmelshausen into his novel. A counterpart in Habsburg service was the Swiss patrician Franz Peter König, ennobled in 1624 as von Mohr, who distinguished himself in skirmishes around Lake Constance in the early 1630s. As these background sketches indicate, such men generally came from relatively humble backgrounds and made reputations and fortunes through daring exploits. They never rose to command armies and were often difficult to control. König was dismissed after becoming embroiled in a feud with the highly disagreeable Wolfgang Rudolf von Ossa, Habsburg military commissioner for south-west Germany.

Widerhold acted nominally in the name of Duke Eberhard III of Württemberg, but pursued his own agenda. Mixing terror with benevolence, he spared the immediate vicinity of the Hohentwiel and concentrated on longer-range raids against Catholic communities, forcing 56 villages, monasteries and hamlets to provision his garrison that rose to 1,058 men and 61 guns by the end of 1638. He was well-supplied with intelligence from friendly villagers who often participated in his plundering expeditions. He returned the favour on his death, leaving a large endowment for the local poor. His exploits became legendary. Once he caught the bishop of Konstanz out hunting and stole his horse and silver, and later he netted 20,000 talers by capturing the local imperial war chest in Bahlingen.

Blockaded since Nördlingen, Widerhold agreed to remain neutral after February 1636 because of renewed talks to include Württemberg in the Prague amnesty. Ferdinand III made surrender a condition for restoring Eberhard III in 1637, but Widerhold ignored ducal orders to comply and declared for Bernhard in February 1638. He remained a constant thorn in the Habsburg side, not least by raiding the Tirolean enclaves, and did not submit to ducal authority until 1650.

#

By draining other regions of their troops, Ferdinand III managed to collect 44,000 men in Bohemia by January 1640. Of these, only 12,400 were available as a field army under Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, reinforced by 4,100 under Hatzfeldt who had wintered in Franconia. Piccolomini was down to 13,000 in Westphalia, while the Saxons mustered 6,648, or only a quarter of their strength five years earlier. The Brandenburgers had effectively been knocked out. The Bavarians still totalled about 17,000 men, most of whom were on the Upper Rhine where there were perhaps 10,000 in total, including a few Imperialists. The rest were in winter quarters around Donauwörth and Ingolstadt. As these figures suggest, it was now very difficult to launch major operations in more than one region at a time.

His enemies were in a similar position. Banér was reduced to 10,000 effectives, while the other Swedish commanders had only enough men to hold their current positions. Banér had little choice but to evacuate Bohemia in March and fall back the way he had come the previous year to join Königsmarck at Erfurt. The units left to hold Saxony were defeated at Plauen on 20 April 1640, forcing the garrison in Chemnitz to surrender while most of the others abandoned their positions.

The challenge over the coming two years was for France and Sweden to establish a viable framework for military and political cooperation that had to include the Hessians and Guelphs, while Ferdinand pinned his hopes on frustrating this with one last effort to rally all Germans behind the Prague settlement. The emperor’s preference for negotiation was cruelly exploited by the Guelphs and Hessians who had used the winter to gather their strength and now declared their hand in May 1640. Duke Georg did this openly by sending troops to Banér, counting on Swedish help to prevent an invasion of Hildesheim. He nominally mustered 20,000, but in fact had 6,000 at Göttingen and garrisons along the Weser, plus a field force of 4,500 under Klitzing. Amalie Elisabeth acknowledged her French alliance in March, but still promised to respect the truce in Westphalia. With French agreement, Melander moved the 4,000-strong Hessian field force east to the Eichsfeld in May to reinforce Banér. Richelieu summoned de Longueville from Italy, hoping that he possessed sufficient personal authority as a duke to master the 8,000-strong Bernhardine field army. This moved back down the Rhine to join the allied concentration.

The emperor was obliged to match these moves. He still hoped to win over the Hessians and so accepted Amalie Elisabeth’s assurances. Nonetheless, Wahl, the new Cologne commander, was authorized to recover the positions her troops had seized over the last two years in breach of the truce. Hessian garrisons also became bolder, now raiding Paderborn. Piccolomini followed Melander east and joined Leopold Wilhelm at Saalfeld, south of Erfurt, on 5 May. They entrenched to block the way into Franconia. After a two-week stand-off, Banér fell back north-west into Lower Saxony, alarming the Guelphs who feared he would abandon them. Once they had promised another 5,000 men, he marched south again to Göttingen and Kassel. Leopold Wilhelm shadowed him, moving through Hersfeld to entrench again at Fritzlar in August. It was cold all year, the summer was wet and miserable and food proved hard to find. Banér’s second wife died and de Longueville fell ill, relinquishing command to Guébriant again. The Bavarian field army arrived from Ingolstadt, bringing Leopold Wilhelm back up to 25,000 men. After another four-week stand-off, Banér withdrew, allowing the archduke to advance north down the Weser to join Wahl’s 4,000 field troops. Together, they took Höxter in October, but the men were exhausted and ill-disciplined. The weather grew windy and even colder. Leopold Wilhelm retreated south to winter at Ingolstadt. Banér left 7,000 to blockade Wolfenbüttel, while the rest of his army made themselves comfortable at the expense of the Guelphs’ villagers.

Seemingly uneventful, this campaign completely shifted the war’s focus to northern Germany, transplanting the ‘little war’ of outposts from Westphalia to the Upper Rhine instead. Under Erlach’s direction, the Bernhardine garrisons operated from Breisach and the Forest Towns in conjunction with Widerhold in the Hohentwiel. The Bavarians retaliated from Philippsburg, Heidelberg and Offenburg, while the Imperialists sortied from Konstanz and Villingen. Neither side managed to spare more than 3,000 men from their fortresses, severely restricting what they could achieve. Erlach helped disrupt plans to besiege the Hohentwiel in 1640 by sending cavalry to collect the Swabian harvest. Claudia scraped together another expedition against Widerhold in 1641, but heavy snow and lack of food forced this to be abandoned in January 1642. Erlach and Widerhold scored the only success, briefly combining the following January to take Überlingen by surprise.

The Freiburg Campaign

The situation appeared promising for the emperor at the beginning of 1644. Sweden’s decision to attack Denmark at the end of the previous year removed the threat to the Habsburg hereditary lands. The forces there were reduced to 11,000 men under the rehabilitated Field Marshal Götz, allowing Ferdinand to mass 21,500 under Gallas who marched down the Elbe to help the Danes. Buoyed by their success at Tuttlingen the previous year, Mercy’s Bavarians totalled 19,640, or twice the size of France’s Army of Germany despite Mazarin spending 2 million livres to rebuild it during the winter. This was the first time since 1637 that the emperor and his allies began the year with an army large enough to go on the offensive on the Upper Rhine.

General Turenne had been recalled to command in Alsace, but his forces were too weak to fulfil Mazarin’s expectations of conquering land beyond the Black Forest. Mercy attacked instead, retaking Überlingen on 10 May, eliminating the last French gain from 1643. Having been repulsed from the Hohentwiel, he left 1,000 men to blockade Widerhold’s garrison and crossed the Black Forest to recover the areas lost in the 1638 campaign. Turenne was forced to abandon his own advance through the Forest Towns, double back into Alsace and re-cross to save Breisach. Duke Charles broke off another of his periodic negotiations and renewed raiding into Lorraine. Mazarin was obliged to redirect d’Enghien from covering Champagne to retrieve the situation on the Rhine. Despite dashing 33km a day, d’Enghien arrived too late to save Freiburg, which had surrendered to the Bavarians after a prolonged bombardment on 29 July.