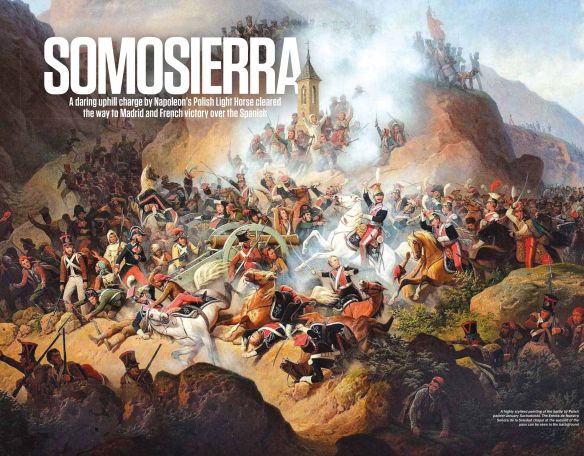

One of the most famous light cavalry charges of the era was made by the Polish Chevaux-Legers regiment at Somosierra, during the 1808 campaign in Spain. This charge demonstrates not only the abilities of light cavalry on the battlefield, but also the dramatic impact that a cavalry charge could have upon an enemy force and how a well-conducted charge could completely unhinge even the most formidable defensive position.

In 1807, Portugal broke with Napoleon’s Continental System, under which an economic embargo was placed on Britain, and a French army was deployed to force it back into line. The French war in Portugal required that Napoleon secure a long supply line across the territory of his ally Spain by placing garrisons and depots in strategic towns. The Spanish grew resentful of the large number of French troops marching across their nation with impunity.

With the situation growing increasingly volatile, Napoleon deposed the Bourbon monarch of Spain and placed his brother Joseph Bonaparte (1768-1844) on the throne, thereby making Spain a vassal state of his sprawling empire. The Spanish had no great love for their former king, but swiftly grew to revile Joseph Bonaparte – and the revolutionary political and social system which he represented – even more. In May 1808, an insurrection broke out against Joseph’s rule and he was forced to flee Madrid. The revolt spread, and soon the Spanish Army itself took the field against its erstwhile ally.

Napoleon determined to squash this uprising before it could gather momentum. He formed the Army of Spain and personally led it across the Pyrenees to restore his brother to the throne. Napoleon scored a series of small victories over the Spanish, and in the autumn of 1808 he led a main strike force of approximately 40,000 men on Madrid. His army advanced on the Spanish capital from the north, where the main road wound up through a high mountain pass, at the top of which sat the village of Somosierra.

Spanish general Benito San Juan (d. 1809) attempted to buy time for the Spanish army to organize resistance and defend its capital while hoping for British military support to arrive. Napoleon wanted to make a quick advance, seize the capital and restore his brother to the throne there as a critical first step to returning order to the country. Besides, speed was vital to the French cause, since the longer Madrid remained in Spanish hands, the more the insurrection would be encouraged and grow in strength.

On 29 November 1808, the lead elements of Napoleon’s army approached the pass at Somosierra, only to find it occupied by Spanish artillery, arranged in three batteries of two guns each that blocked the road at intervals, plus 10 guns mounted in an improvised fort that straddled the road at the very top of the pass. Approximately 9000 Spanish infantry were also ensconced along the road, on the slopes of the mountains overlooking the pass and in the fort itself. Napoleon ordered General Francois Ruffin’s (1771-1811) infantry division, part of General Claude Victor’s (1764-1841) corps, to take the pass and clear the road.

Ruffin’s men came under a galling fire from the well-positioned Spanish and made little headway on the position. As daylight began to fade, Napoleon decided to call off the attack and resume it in the morning, when the rest of his army would have closed up and thus be prepared to exploit the anticipated breakthrough.

Early on the morning of 30 November 1808, General Ruffin’s men moved to the attack, yet once more they were driven to ground by cannon and musket fire from the well-placed Spanish defenders. The steepness of the slopes forbade any rapid movement to flank the position, and the road itself was narrow and winding, twisting back and forth to help ease the ascent, forcing an attacking army to linger under the Spanish guns. Napoleon rode forward to a point of observation, escorted by the third squadron of the Polish Chevaux-Legers (light cavalry) regiment.

Enter the Poles

The ancient state of Poland had been systematically dismembered in the late eighteenth century by the combined assaults of Austria, Prussia and Russia, culminating in the final blow of 1792 when Poland disappeared from the map. The kingdom was divided as spoils of war amongst the three great powers, and while Poles served in the armies of their occupiers, they yearned for freedom. When Napoleon defeated Austria, Prussia and Russia during his brilliant series of campaigns from 1805 to 1807, the Poles believed they had found their deliverer. Shortly after his conquest of Poland’s ancestral capital of Warsaw, they began to flock to Napoleon’s cause.

In 1808, Napoleon created the Grand Duchy of Warsaw as a satellite state of the French Empire, amidst general rejoicing throughout the Polish lands. Although Napoleon stopped short of granting Poland full independence (mainly because of his delicate relations with Russia), he was sympathetic to their cause, and the Poles loved him for it. In order to show their support for the French Empire, a cavalry regiment was formed from the sons of the finest noble families in Poland and incorporated into the ranks of the Grande Armee. This was the Polish light cavalry regiment, and Spain was to be its first campaign.

As Napoleon was busy reconnoitring the Spanish positions near the pass, cannonballs crashed to earth near the emperor and his staff. The enemy fire angered rather than frightened him, since he could not believe Ruffin’s infantry was being held in check by Spanish troops, which he believed to be far inferior to his own. Growing increasingly frustrated, he ordered General Hippolyte Pire (1778-1850) to provide cavalry support for the attack. The French horsemen rode forward into the fight, but the combination of constrictive terrain and heavy enemy fire conspired to drive them backwards. At length an exasperated Pire rode back to Napoleon and told him it was impossible to force the pass.

An already simmering Napoleon flew into a rage at this news. He slapped his riding crop against his boot and exclaimed: ‘Impossible? I don’t know the meaning of the word.’ He then turned to Colonel Jan Kozietulski (1781-1821), commander of his Polish escort squadron. The emperor pointed towards the pass and ordered: ‘Take that position, at the gallop.’

In all likelihood Napoleon was only referring to the first Spanish gun emplacement, which had brought his staff under fire and was the only emplacement that he could see in the fog and smoke of battle. In reality, the Spanish position consisted of three successive gun emplacements spaced along the road, with supporting infantry units, crowned by a fort mounting a total of 10 guns at the summit.

The Charge Begins

Although the exact meaning of the order was unclear, Colonel Kozietulski made no attempt to clarify his instructions. Instead he saluted Napoleon then galloped to the front of his command and addressed the men. French officers overheard the exchange and thought the order madness – a single cavalry squadron to attack what an infantry division had failed to move? Yet in front of their incredulous eyes, the Poles arranged themselves into columns of four, in order to climb the narrow road they had to use, and prepared for battle. Impetuously, a number of French officers joined the Polish horsemen, as did another platoon of Polish horsemen who had just returned from a reconnaissance mission.

Officers shouted commands for the rest of the Polish regiment as well as other French cavalry units to deploy forward to back up the attack, but Kozietulski did not await this support. Instead, he placed himself at the head of his small command and shouted to his men: ‘Forward you sons of dogs, the Emperor is watching.’ A great cheer of ‘Vive l’Empereurl’ swept through the ranks, and the Polish horsemen drew their sabres, then dug spurs into the flanks of their horses as the squadron surged forward.

A hail of musketry and cannon fire greeted the cavalry’s approach. Horses and riders were sent tumbling, but onwards they came. As they wound their way up the hill, their horses laboured to increase their speed on the steep slope. Astonished Spanish gunners hurriedly shifted their pieces to place fire on this new threat as the cavalry swept past Ruffin’s incredulous infantrymen.

Grapeshot whizzed through the air from the three Spanish two-gun batteries on the road, and saddles were emptied, but the charge went forward. The Poles hacked to left and right with their sabres and in a rush overran the first battery, giving no quarter and expecting none in return.

Beyond the Call of Duty

Although they had already fulfilled the mission set out for them by Napoleon, the cavalry did not halt. Instead, they continued their climb up the pass. Musketry exploded into them from either side of the road from supporting Spanish infantry and more horsemen fell. The second battery now came into view and the Poles roared through it at full gallop, scattering gunners and infantry before them as they plunged deeper into the Spanish positions. As at last they reached the crest of the pass, the ground levelled and the Poles urged their frothing mounts into a thundering gallop that exploded into the final Spanish battery. The surprised gunners were cut down where they stood, but with their horses blown and over half their number down, the Polish squadron collapsed in a heap, still short of their final objective.

Their charge, however, had unhinged the Spanish defensive positions. With all eyes fixed on the Poles, General Ruffin’s infantry were at last able to move forward and they came on at the trot with bayonets fixed. Then, from the rear, the blare of bugles resounded as the remainder of the Polish regiment and a French cavalry regiment came roaring up the road. Together with the infantry they struck the final Spanish defensive position at the summit like a thunderbolt and blew through this last line of resistance to make themselves masters of the pass of Somosierra. As the remnants of the Spanish army clambered for safety across the hills and melted away as an effective fighting force, the battle was won and the road to Madrid lay open.

Slaughter in the Pass

Napoleon had observed the attack through his spyglass, and as he saw the French colours mount the summit of the pass, he snapped his telescope shut and gave the order for a general advance. He then spurred his horse forward, as aides and cavalry rushed to keep up with him. He galloped up the winding road, noting the twisted bodies of men and horses, some still struggling for life, which lay strewn about.

Among the first of the imperial headquarters staff to arrive at the pass was Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier (1753-1815). A dying Polish officer lying on the ground raised himself on an elbow and, pointing to the captured batteries, gasped out: ‘There are the guns, tell the Emperor.’

At length, Napoleon himself reached the pass. Amidst the debris of the third Spanish battery, the apex of the Poles’ wild charge, Napoleon found Lieutenant Andrzej Niegolewski (1787-1857), who had been wounded 11 times in the course of the charge, sitting on the ground, barely conscious, propped against one of the captured guns. The emperor called for a surgeon and then dismounted. He knelt beside Niegolewski, clasped his hand and thanked him for the courage he had shown that day. He then removed the Legion d’honneur from his own breast and pinned it to Niegolewski’s chest. The emperor stood and in a loud voice proclaimed that the Poles were the bravest cavalrymen in his army. As the survivors reformed and moved to the rear, they passed the serried bearskins of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard. Under orders from the emperor, the Guardsmen, moving with their customary machine-like precision, presented arms as the shattered remnants of the Polish regiment passed.

In his official report, Napoleon gave full credit for the victory to the Polish horsemen. In recognition of their courage, he later awarded the Legion d’honneur to 17 Poles who had taken part in the charge. Napoleon ordered the Poles, later reequipped with lances, to become part of his Old Guard. They would faithfully follow their emperor across Europe and onto numerous other battlefields.

Even after his defeat and exile in 1814, the Poles remained loyal to Napoleon and rallied to his cause once more during the Hundred Days of 1815. Yet none of the host of battles they would later engage in would ever remain as gloriously preserved in the national memory of Poland as the wild charge they made at Somosierra.