There were six types of turrets used in the Maginot Line, in different sizes and styles. The turrets ranged from 1.98m in diameter for the machine-gun turret to 4m for the 75mm M1933 turret for two guns. The 135mm and 81mm housed curved fire mortars. The mixed-arms turret was a refurbished M1905 75mm gun turret left over from World War I.

In the mid-1920s the French high command appointed a new set of commissions to study the future defences of the French border in the north as well as in the Alps: the Commission de défense du territoire (CDT), Commission de défense de la frontière (CDF) and Commission d’Organisation des Régions Fortifiées (CORF). The CDF was the main decision maker. Composed of engineering and artillery experts, it met on multiple occasions to debate the nature of the fortifications to be built and to decide which types of artillery and infantry pieces to install in the forts.

The removal of 75mm guns from the flanking casemates at Verdun led to the diminished functionality of the forts. It became a policy of the CDF and later the CORF (tasked with implementing the ideas of the CDF) to create casemate and turret pieces that could not be used outside of the forts. Thus, the piece and the envelope in which it was placed were to be indivisible. This included both the gun barrel and the carriage. The new forts were designed to ensure flanking of the intervals with casemate guns; long-range, short-barrelled cannons in retractable turrets for frontal action; and heavy, medium-range mortars to hit areas hidden from direct fire. The forts would keep infantry troops and sappers at bay with mortars, machine guns and automatic rifles.

The 75mm M1897 cannon was selected as the basic cannon-howitzer for flanking protection. A shortened version of the gun (with the barrel cut to 30cm in length) was selected for installation in the 75mm M1933 turret. It was modified to fit a new carriage, affixed with a hydraulic brake mechanism to give it a shorter recoil in the enclosed space, and a ball joint on the end of the barrel to fit snugly in the embrasure. To cover the ground that could not be reached by the longer-range cannon-howitzer, the French also developed the 75R32 gun turret, a mortar with an even shorter barrel. Finally, the 135mm M1932 Lance-Bombe heavy mortar had no precedent in French artillery history. The CDF proposed the concept of a bomb launcher, like a trench mortar, in a retractable turret to defend a space 3,000m to 4,000m from the approaches to the fort.

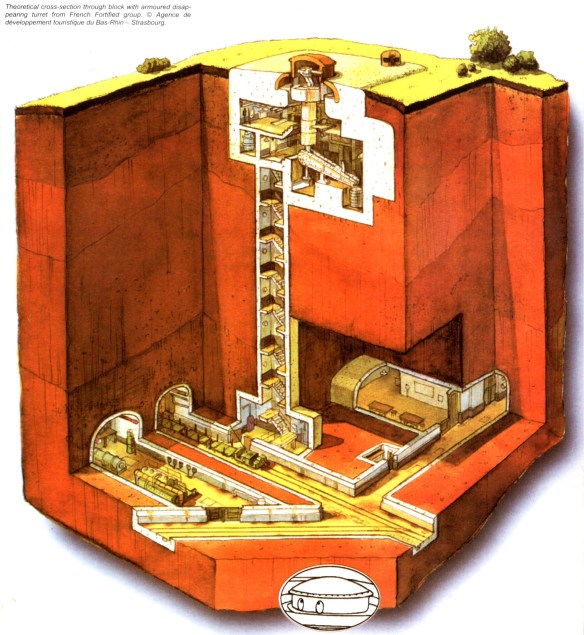

In general, the armoured turrets of the Maginot Line were built along the same principles as the earlier models. The guns were protected by a thick steel cap within steel walls. This cylinder, called the gun compartment, rested on a pivoting tube that was connected at its base to a balancing arm and a counterweight. The turret was built to function by electric power but it was equipped with a backup manual system. The shells were stored adjacent to the turret and lifted up to the gun compartment in an electrically operated lift. Spent shells dropped out of the gun breech into a chute that fed them to the lower floor of the bloc where they were recovered and re-used. Each turret was positioned in a concrete well and protected by a thick layer of reinforced concrete. The turret blocs were located on the surface and connected by staircase or elevator/staircase combination to the lower level of the underground fortress, the ouvrage. The turret blocs functioned efficiently with a highly trained crew to operate the guns, which were swift to fire and highly accurate.

Maginot Line 1940

In at least one regard, the Maginot Line proved to be an unqualified strategic success. The French created it with several major objectives in mind, such as channeling the Wehrmacht’s initial thrust into Belgium, thus keeping initial fighting off French soil. The Line achieved this goal, though the French lacked the mobile armored forces necessary to exploit it and deal a knockout blow to the German advance.

The German high command, or OKW, recognized France as the next target after Poland. Overrun in 1939 by Nazi attacks from the west and Soviet incursions from the east, Poland furnished an excellent proving ground for Blitzkrieg tactics. The fighting there also highlighted the weakness of certain German weapons systems such as the Panzer I and II tanks. Production therefore shifted to more effective Panzer IIIs and Panzer IVs.

The invasion of Poland prompted Britain and France to declare war on Germany, starting World War II. Neither nation figured out to do next, however, leaving Hitler with the initiative. Conquering France and using that conquest as a springboard to either coerce the British into backing out of the war (Hitler’s preferred solution, as he hoped for an alliance with the English) or to invade the “Sceptered Isle” followed as the logical next step in the struggle.

The OKW initially believed no invasion of France could hope to succeed prior to 1942. However, a much accelerated timetable proved possible with the power of modern transport and paratrooper action to launch a swift, successful offensive, the kind of campaign seen in the Germans’ lightning conquests of Denmark and Norway.

As the French predicted, the Germans entered Holland and Belgium first on May 10, 1940, with the intention of both outflanking the Maginot Line and drawing its defending forces away to the north. A French army under Henri Giraud moved to the support of the Netherlands, but the Wehrmacht’s “new style” of warfare prevented him from his intended goal of linking up with the main Dutch military force. The Germans used paratroopers – the elite Fallschirmjagers – to drive a wedge deep behind enemy lines, preventing the French and Dutch from linking up, and the Dutch army’s main concentration fell back northward while Giraud’s French forces withdrew to the south. When German bombing set fire to Rotterdam, Holland surrendered on May 14, 1940, after which the Germans sent fire engines to assist in halting the blaze.

The Wehrmacht also struck more rapidly than its enemies anticipated in Belgium. Glider-borne troops seized the main Belgian fortress in a few hours on May 11th, and Fallschirmjager took key river bridges, once again exerting powerful control over the battlefield and cutting off much of the Allies’ potential for tactical and strategic maneuver. French General Georges Blanchard led the First Army forward nevertheless, and in two tank battles, he managed to halt the Germans temporarily, but events elsewhere proved the undoing of the French defense.

Rather than throw the main weight of their attack either into Belgium – where they knew the French awaited them – or against the powerful Maginot Line, the Wehrmacht sent a deadly thrust through the Ardennes Forest instead. The French judged the Ardennes to be largely impassible for tanks, which it had been during World War I, but the advanced tanks of the late 1930s negotiated the forested and soft terrain with little difficulty. The French left the Ardennes as a leafy gap in their national “armor,” a narrow but crucial weak point between the Maginot Line and the armies supporting Belgium.

While the French concentrated their attention on Belgium, 1,222 tanks, 400 other vehicles, and 134,000 men under the famous Panzer General Heinz Guderian rolled steadily forward down the labyrinthine roads of the Ardennes. Arriving at the River Meuse at Sedan on May 13th, the Germans immediately attacked across the river. The stunned French defenders, manning small, isolated bunkers rather than massive ouvrages, found themselves under a torrent of fire and steel delivered from the sky by 1,000 Luftwaffe aircraft, including the dreaded Stuka dive-bombers, while the German engineers forced a crossing. Small parties of Wehrmacht soldiers crossed immediately in rubber boats to knock out the bunkers, as recounted by one Staff Sergeant Rubarth, soon to be a recipient of the Iron Cross for his actions in taking no less than seven of these structures: “I land with my rubber boat near a strong, small bunker, and together with Lance Corporal Podszus put it out of action. … We seize the next bunker from the rear. I fire an explosive charge. In a moment the force of the detonation tears off the rear part of the bunker. We use the opportunity and attack the occupants with hand grenades. After a short fight, a white flag appears. … Encouraged by this, we fling ourselves against two additional small bunkers.” (Jackson, 2004, 44-45).

The French failed to counterattack this penetration successfully, and within 48 hours, German armored units had plunged deep into French territory to the west. Many French divisions in the area, made up of second-rate units comprised of reserve troops and pensioners, panicked and fled without firing a shot.

The French formed a defensive line deeper in the countryside under General Maxime Weygand. Here, the French gave a better account of themselves, fighting with immense courage despite their lack of hope until the concentrated attacks of well-equipped and highly aggressive Wehrmacht infantry, deep penetration by Panzer attacks, and the relentless dive-bombing of the Luftwaffe compelled them to fall back. “The words of a German soldier provide an apposite summary of events after 5 June when the French Army was fighting against odds of three to one on the Weygand Line: ‘In the ruins of the villages, the French resisted to the last man … Here, on the Aisne, the French regiments were determined to defend every last route to the heart of France, in a battle that would decide the fate of their country. The poilu had done his duty.” (Sumner, 1998, 4).

After everything that had gone into building it, the Maginot Line proper only saw action following these opening disasters. With the British in full retreat from Dunkirk and the Panzers pushing towards Paris, the Germans felt secure enough to attempt reduction of the Maginot Line on their flank. The first encounter with the Maginot Line involved four petit ouvrages on the extreme western end of the fortifications, known as the “Maginot Line Extension.” The Germans attacked the westernmost of these from May 17-18 after a preliminary bombardment that annihilated the ouvrage’s antitank defenses and barbed wire entanglements. A small, relatively weak position armed only with 25mm cannons and machine guns, “La Ferte” still resisted as vigorously as possible. German combat engineers used explosive charges and 88mm guns to blow open a number of the ouvrage’s turrets, after which they dropped charges inside. Return fire ceased late on May 18, and when the Germans cautiously entered the ouvrage on the morning of May 19, they found the approximately 100 defenders dead but mostly unwounded; they had apparently asphyxiated when the ouvrage’s ventilation system failed. Their commander, Lieutenant Bourguignon, asked his superiors repeatedly via radio for permission to evacuate due to uncontrolled fires in the fortification, but the French command refused to listen to him and the French soldiers slipped into their final sleep during the night.

Following this appalling failure, the French sector commanders, not wishing to vainly sacrifice more men, ordered the other three ouvrages of the Maginot Line extension evacuated, but events overtook the French defenders before they could carry these orders out.

The initial German thrust bypassed the city of Maubeuge and its defenses, but the OKW tasked following units with seizing the city in late May, despite the French emplacements defending it. The Maginot defenses in the area consisted of four ouvrages, named Bersillies, Sarts, La Salmagne, and Boussois, interspersed with 7 interval casemates, 13 casemates forming a 6-mile line in the Mormal Forest, and various small blockhouses. The French 101st Division of Fortress Infantry manned these positions, supported by 120mm and 155mm artillery batteries.

The 5th Panzer Division and the 8th and 28th Infantry Divisions of the German Army advanced to seize these defenses on May 18, and though heavily outgunned, the French defenders fought valiantly, pinning the German forces in place for four days before the Wehrmacht finally overcame them. “Boussois was the first to come under fire on 18 May. Although its 25-mm guns were no match for German 150-mm cannons and deadly 88-mm Flak, the little fort resisted gamely. On 20 May, […] The mixed arms turret of Block 2 at Boussois suffered some damage and was unable to retract, but it was repaired in the dead of night. On 21 May, the powerful interval casemate of Heronfontaine repelled a German assault with its mixed-arms turret.” (Kaufmann, 2006, 162).

The Germans pounded the French positions with powerful mortars, including 210mm mortars, and repeated Stuka dive-bomber attacks, but the cement and steel resisted these strikes and the French fought on. The Germans finally reduced the casemates by attacking them from their blind side and using 88mm guns point blank. This damaged the ventilation systems sufficiently so that the French surrendered to avoid death by asphyxiation.

Meanwhile, the four petit ouvrages proved tougher nuts to crack. The Germans eventually forced their evacuation or surrender by use of demolition charges, 88mm gun fire directed point-blank at firing embrasures, and flamethrowers. The Wehrmacht troops found it necessary to lay down enormous smoke-screens so that they could approach the emplacements across open ground to lay charges.

On May 22nd, the Germans attempted the reduction of Fort Boussois. Their first dawn attack came to grief when their supporting artillery fire fell short and killed or wounded large numbers of attacking troops, forcing them to fall back. Later in the morning, a massive artillery bombardment forced the French to retract their eclipsing turrets into their wells, reducing defensive fire enough for German combat engineers to climb on top of the ouvrage. Locating the ventilation system conduits, the Germans dropped explosive charges in, knocking out the air purification systems. Faced with a slow but inevitable death by asphyxiation, the gallant French defenders surrendered at noon.

That afternoon, the ouvrage La Salmagne also fell. Smoke rounds enabled German combat engineers to climb atop it. These men used axes to destroy many of the machine guns protruding from firing embrasures and began their search for the ventilation shafts. The French, knowing the game was up, surrendered before their ventilation failed. The French evacuated their last positions on May 23rd, but the Maubeuge fight had demonstrated the toughness of even petit ouvrages and casemates against the era’s heaviest weapons.

The slow, piecemeal reduction of the Maginot Line continued, though the Germans focused most of their efforts elsewhere for a time. The Wehrmacht took a few casemates here and a petit ouvrage there, but they were mostly content to leave the line be for a time. This changed on June 14 when the Wehrmacht launched Operation Tiger against the Sarre Gap. This relatively weakly defended section of the Maginot Line lay between the two massively fortified, modern sections of the line guarding the frontier from Switzerland to the Ardennes. This southward offensive planned to pierce the Gap, defended only by blockhouses and dikes rather than a continuous line of ouvrages, with 11 infantry divisions against 5 French regiments, plus Luftwaffe air support and a colossal supporting force of 1,000 artillery pieces.

The Germans commenced their attack with vast artillery bombardments, followed by large infantry and vehicle attacks. However, the French defenders of the Sarre Gap fought back ferociously. The blockhouses, despite their small size, made good use of interlocking fields of fire to mow down the German attackers. The French also opened the gates to prepared “flood zones,” filling whole areas of the front with river water and thus further impeding the German advance. Pre-sighted French artillery pounded the Wehrmacht with lethally accurate shelling.

The German commander, von Witzleben, almost called a full retreat at nightfall on June 14, as the French had repulsed most of his attacks with heavy losses and the few gains appeared tactically insignificant. However, a German patrol in the Kalmerich Forest captured a French courier bearing a retreat order, which convinced Witzleben to order another attack the following morning. The French, falling back under cover of darkness, found themselves overtaken by a fresh German offensive the following morning. Once again, the French soldiers halted the immensely superior numbers of the Germans by using the defensive positions further from the border as a force multiplier. On the night of the 15th, however, they withdrew rapidly, enabling an unopposed German breakthrough in the Sarre Gap on June 16th. At this point, the Germans had broken the Maginot Line’s remaining defenses in two.

Despite the breakthrough in the Sarre Gap, the Metz and Lauter halves of the Maginot Line remained unconquered. Massively fortified and heavily armed, the fortress system readily survived the loss of the Sarre section at its center and continued to hamper German troop deployments across the border.

The Germans launched Operation Little Bear, a Rhine crossing at another weak point in the Maginot Line, on June 15th. 400 pieces of artillery destroyed many small casemates and bunkers outright, but the ouvrages proved immune, as usual, to both artillery fire and Stuka dive-bombing. By June 16th, the French retreated from their riverbank positions, but they did so only to occupy even tougher positions in the Vosges Mountains, limiting the effect of Little Bear and leaving the Maginot Line still essentially intact and combat-ready. This situation did not change until after the armistice on June 25th, 1940.

Nothing highlights the fact that the Maginot Line could have proved decisive if better supported and used as a base for aggressive counterattacks based on flexible, largely independent commands than the reality that its defenders were the last French soldiers to surrender. “[W]hen the armistice took effect, the main fortifications of the Maginot Line were still intact and capable of continuing the fight. Although active combat had ended, several fortress commanders refused to admit defeat. Remaining defiant, they surrendered only after being ordered by Gén. Georges, and then only under protest. In early July, a week after the rest of the French Army laid down arms, the last fortress was handed over by its crew to the Wehrmacht.” (Romanych, 2010, 90).

Ironically, the fortress system whose name has become a synonym for a fear-inspired defensive strategy actually stood as the last defiant bastion of France during the Nazi conquest of 1940. Though this defiance remained largely symbolic, the final spark of French fighting spirit kindled for a moment in the Maginot Line.