The end of the war had found the Soviet Union in possession of much of the Baltic littoral, including Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and East Prussia, and in occupation of Poland and the eastern zone of Germany. The USSR had also occupied Finnmark, the northernmost Norwegian province, and the Danish-owned Baltic island of Bornholm in 1945, primarily in order to take the surrender of the German forces; both were, however, handed back peacefully, Finnmark in late 1945 and Bornholm in the spring of 1946.

Despite this, Denmark and Norway found themselves faced with a palpable Soviet threat in early 1948 and started to examine the question of a defence pact, although initially they considered only limited membership based on a ‘Nordic’ grouping. These countries wished to avoid becoming involved in the Great Power rivalry between the USA and the Soviet Union, and were also keen to avoid becoming embroiled in the tensions in continental Europe immediately to their south.

The most powerful and prosperous of the Nordic countries was Sweden, which had successfully maintained its armed neutrality throughout both world wars and wished to continue to do so. Thus, in the immediate post-war period Sweden performed a delicate balancing act, making a 1 billion kronor loan to the Soviet Union, but also purchasing 150 P-51 Mustang piston-engined fighters from the USA, followed by 210 Vampire jets from the UK in 1948.

Norway had been occupied by the Germans during the war, partly because of its strategic position, but also because German industry depended upon Norwegian iron-ore production. In the post-war period Norway considered the Soviet threat to be very real, and its leaders began to seek a guarantee of security which would nevertheless not antagonize the Soviet Union.

Denmark was initially well disposed towards the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the war, but became increasingly concerned by the events in eastern Europe. In the spring of 1948 the country was swept by a rumour that the Russians intended to attack western Europe during the Easter weekend. This rumour turned out to have been ill-founded, but the Danes realized that neutrality was no longer a serious option and that some form of multinational co-operation was therefore essential. During its Second World War occupation by the Germans, Denmark, unlike many other occupied countries in western Europe, had been almost totally isolated from the UK and had been forced to look to its neighbour Sweden for what little help and support that neutral country could offer. It was only natural, therefore, that in the late 1940s it should wish to explore the possibilities of an alliance with Sweden.

On 19 April 1948 the Norwegian foreign minister, Halvard Lange, made a speech in which he publicly expressed interest in a ‘Nordic’ solution – by which he meant one involving Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

Finland would also have been a natural member of a Nordic grouping, but the USSR made that impossible. The peace treaty had imposed strict manpower ceilings on Finland’s armed forcesfn3 and, as if this was not enough, the country was effectively neutralized by the treaty of ‘Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance’ that the Soviet Union had forced it to sign on 6 April.

The Norwegian initiative was considered by the Swedish parliament, which authorized its government to consult Denmark and Norway on the subject. Throughout these discussions the basic Swedish position was that Sweden would not stretch its neutrality beyond a Nordic grouping, which would be non-aligned and strong enough to remain uncommitted to either East or West; in particular, Sweden was not prepared to participate if any other members had bilateral links to outside parties. On the other hand, the Norwegians considered that their interests would best be served by joining an Atlantic pact (i.e. one involving the United States), while the Danish prime minister sought to find common ground between the other two parties. Having established their initial positions, in September 1948 these three countries set up a Defence Committee whose task was to study the practical possibilities of defence co-operation.

At the political level, in October 1948 the Danish and Norwegian foreign ministers sounded out the US secretary of state, George Marshall, about the likely US attitude to a Nordic pact. He told them that it would be very difficult for the US government to give military guarantees to a neutral bloc, and that any supplies of military equipment would inevitably take lower priority than to formal allies.

In January 1949 the Nordic Defence Committee reported that a trilateral military alliance would increase the defensive power of the three participants both by widening their respective strategic areas and through the benefits of common planning and standardization of equipment. All this, however, could be achieved only if Denmark and Norway underwent substantial rearmament. And even if all of this were achieved, the military experts advized that the Nordic pact would be unable to resist an attack by a Great Power (by which, of course, they meant the Soviet Union).

Having received the military report, the three prime ministers and their foreign ministers met on 5–6 January 1949 and discussed a variety of topics, including how to achieve the rearmament of Denmark and Norway. Then on 14 January the US government announced publicly what it had already advised in private, namely that the priority in provision of arms would be to countries which joined the US in a collective defence agreement. The Nordic prime ministers and foreign ministers reconvened at the end of the month, and on 30 January they announced that it was impossible to reach agreement; the potential Nordic pact was thus consigned to history.

NATO

At the start of the Washington discussions it was clear that membership of the proposed alliance would include the Brussels Treaty powers (the Benelux countries, France and the UK), Canada and the United States, but there was some discussion over other potential members.

It was considered highly desirable that Denmark and Norway should join the proposed alliance, and, if possible, Sweden as well. These were long-established democracies and were as much threatened as any other country in Europe; indeed, in 1948–9 Norway was probably the most threatened of them all. Further, they occupied very important strategic positions. Denmark sat astride the western end of the Baltic, dominating (with Sweden) the Skaggerak and the Belts; it also owned the island of Bornholm in the middle of the Baltic. Of greater importance to the United States, however, was Danish ownership of Greenland, which was a vital stepping-stone in the air route from the United States to Europe at a time when transport aircraft had a comparatively short range. Norway was also strategically important, since it lay along the southern flank of the Soviet Union’s naval routes to the Atlantic and shared (with the USSR) the island of Spitsbergen. Sweden, however, was adamant that it would not abrogate its neutrality, and its membership was not pursued.

NAVIES

Denmark

Denmark had virtually no navy at the war’s end in 1945, but on joining NATO in 1949 it was allotted the role of Baltic defence, in which it was joined by West Germany when the latter became a NATO member in 1955. Denmark’s second naval task was the mining of the Kattegat and the Belts to deny the Soviet fleet an exit into the North Sea. The navy also had the national task of patrolling Greenland waters.

To fulfil these missions, the Danish navy maintained a small number of frigates, all designed and built in Denmark, together with three unusual corvettes (Nils Juel class), and also provided a small number of submarines and fast-attack craft. To meet its minelaying commitment the Danish navy was equipped with a number of dedicated minelayers.

The Danish navy found itself facing a major re-equipment problem in the 1980s, which unfortunately coincided with a general domestic feeling of opposition to defence (it was the time of NATO’s ‘twin-track’ approach to the Soviet SS-20 programme). As a result, the navy produced a novel type of warship, the Stanflex 300 (Flyvefisken class), which employed a single basic hull constructed of fibreglass and a common propulsion system, but with changeable weapon and sensor containers, which enabled the ships to be employed and equipped for either fast attack, minelaying, mine counter-measures (MCM) or ASW duties.

West Germany

The West German navy (Bundesmarine) was created in 1956 and from then on was firmly integrated within NATO, its principal tasks being the defence of the Baltic and North seas, in conjunction with other NATO navies. Initially the ships were a mixture of surplus US and British types, with a few German-built ships which had been transferred to the Allies as war reparations being returned as well, but the warship-building industry was rapidly restored.

The largest units were destroyers, of which the first six were ex-US Fletcher-class ships, supplemented in the mid-1960s by four German-designed and -built ships. Next to be acquired were three US-designed Adams-class destroyers and then eight frigates based on a Dutch design. The German navy also provided a large number of fast-attack craft and mine-countermeasure vessels (MCMVs), but, not surprisingly in view of its history, one of its main strengths lay in its U-boats. These were all of German design, and by the 1970s eighteen 500-tonne-displacement Type 206s were in service. West Germany also proved particularly successful in exporting submarines, which helped to sustain its design and construction capability at times when there were no domestic orders.

Norway

Norway occupied a particularly important place in NATO’s maritime strategy, since it lay alongside the only route by which ships and submarines of the Soviet Northern Fleet could sail out into the Atlantic. The Norwegian navy was far too small to challenge the large Soviet surface action groups, and it concentrated instead on anti-submarine warfare, particularly in its many fjords. Its equipment included a number of frigates built to a US design in Norwegian shipyards (the Oslo class), and sixteen small diesel-electric submarines (the Kobben class), which were designed and built in Germany. Replacement of the latter by the new Ula class (also German-built) was just beginning as the Cold War ended. Norway also operated some coastal-attack craft and MCMVs.

Soviet Naval Activity

In the immediate post-war years the only naval units of even marginal significance were three battleships: a Russian vessel dating back to tsarist times and two British ships of First World War vintage, which had been lent to the USSR during the war. One of the latter was returned to the UK in 1949, having been replaced by the ex-Italian Giulio Cesare, which the Soviets renamed Novorossiysk.fn3 There were also some fifteen cruisers – a mixture of elderly Soviet designs, nine modern Soviet-built ships, a US ship lent during the war (and returned in 1949), and two former Axis cruisers, one ex-German, the other ex-Italian. There was also a force of some eighty destroyers, also of varying vintages and origins.

During the 1940s and 1950s these Soviet warships were rarely seen on the high seas, apart from a limited number of transfers between the Northern and Baltic fleets, which tended to be conducted with great rapidity. The only exception was a series of international visits, mainly by the impressive Sverdlov-class cruisers, which were paid to countries such as Sweden and the UK. The navy suffered a major setback in 1955 when the battleship Novorossiysk was sunk while at anchor in the Black Sea by a Second World War German ground mine, an event which led to the sacking of the commander-in-chief, Admiral N. M. Kuznetzov; he was replaced by Admiral Gorshkov.

In the early 1960s, however, individual Soviet units began to be seen more frequently in foreign waters, as did ever-increasing numbers of ‘intelligence collectors’, laden with electronic-warfare equipment. These ships, generally known by their NATO designation as ‘AGIs’, monitored US and NATO exercises and ship movements. The original AGIs were converted trawlers and salvage tugs, but, as the Cold War progressed and the Soviet navy became increasingly sophisticated, larger and more specialized ships were built, culminating in the 5,000 tonne Bal’zam class, built in the 1980s. In addition to such ships, conventional warships regularly carried out intelligence-collecting and surveillance tasks, particularly when Western exercises were being held. Apart from general eavesdropping on Western communications links and studying the latest weapons, such missions helped the Soviet navy to learn about US and NATO tactics, manoeuvring and ship-handling.

The Soviets also put considerable effort into espionage (human intelligence, or HUMINT, in intelligence jargon) against Western navies. This included the Kroger ring in the UK, which was principally targeted against British anti-submarine-warfare facilities, and the Walker spy ring in the USA, which gave away a vast amount of information on US submarine capabilities and deployment.

The growth and increasing ambitions of the Soviet navy were best illustrated by the size, scope and duration of its exercises. The first important out-of-area exercise was held in 1961, when two groups of ships – one moving from the Baltic to the Kola Inlet and the other in the opposite direction (a total of eight surface warships, four submarines and associated support ships) – met in the Norwegian Sea. There they conducted a short exercise before continuing to their respective destinations.

In early July 1962 transfers between the Baltic and Northern fleets again took place, coupled with the first major transfer from the Black Sea Fleet to the Northern Fleet. This was followed by a much larger exercise, extending from the Iceland–Faroes gap to the North Cape, which included surface combatants, submarines, auxiliaries and a large number of land-based naval aircraft. The activity level increased yet again in 1963, and the major 1964 exercise involved ships moving through the Iceland–Faroes gap for the first time, while units of the Mediterranean Squadron undertook a cruise to Cuba. By 1966 exercises were taking place in the Faroes–UK gap and off north-east Scotland (both long-standing preserves of the British navy) and also off the coast of Iceland.

In 1967 the naval highlight of the Arab–Israeli Six-Day War was the dramatic sinking of the Israeli destroyer Eilat by the Egyptian navy using Soviet SS-N-2 (‘Styx’) missiles launched from a Soviet-built Komar-class patrol boat. Not surprisingly, Soviet naval prestige in the Middle East was high, and the Soviets took the opportunity to enhance it yet further by port visits to Syria, Egypt, Yugoslavia and Algeria, employing ships of the Black Sea Fleet.

The following year saw the largest naval exercise to date; nicknamed Sever (= North) it involved a large number of surface ships, land-based aircraft, submarines and auxiliaries. The exercise covered a variety of areas, but the main activity took place in waters between Iceland and Norway. One of the naval highlights of the year, for both the Soviet and the NATO navies, was the arrival in the Mediterranean of the first Soviet helicopter carrier, Moskva.

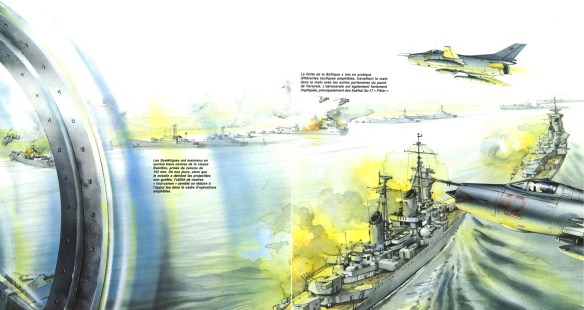

Further exercises and deployments took place in 1969, but in the following year Okean 70 proved to be the most ambitious Soviet naval exercise ever staged. This involved the Northern, Baltic and Pacific fleets and the Mediterranean Squadron in simultaneous operations, with the major emphasis in the Atlantic. A large northern force, comprising some twenty-six ships, started with anti-submarine exercises off northern Norway between 13 and 18 April, and then proceeded through the Iceland–Faroes gap to an area due west of Scotland, where it carried out an ‘encounter exercise’ against units from the Mediterranean Squadron. The two groups then sailed in company to join the waiting support group, where a major replenishment at sea took place. Other facets of the exercise included units of the Baltic Fleet sailing through the Skaggerak to operate off south-west Norway, and an amphibious landing exercise involving units of the recently raised Naval Infantry coming ashore on the Soviet side of the Norwegian–Soviet border.

This was a very large and ambitious exercise, from which the Soviet navy learned many major lessons, one of the most important of which was the falsity of the concept of commanding naval forces at sea from a shore headquarters. Such a concept had been propagated for two reasons: first, because it complied with the general Communist idea of highly centralized power and, second, because it also avoided the complexity and expense of flagships. Once Okean 70 had proved this concept to be impracticable, ‘flag’ facilities were built into the larger ships, although the Baltic Fleet continued to be commanded from ashore.

The exercise which took place in June 1971 rehearsed a different scenario, with a group of Soviet Northern Fleet ships sailing down into Icelandic waters, where they reversed course and then advanced towards Jan Mayen Island to act as a simulated NATO carrier task group, which was then attacked by the main ‘players’. Again, a concurrent amphibious landing formed part of the exercise.

There were no major naval exercises in 1972, but in a spring 1973 exercise Soviet submarines practised countering a simulated Western task force sailing through the Iceland–UK gap to reinforce NATO’s Northern flank, while a similar exercise in 1974 took place in areas to the east and north of Iceland. Okean 75 was an extremely large maritime exercise, involving well over 200 ships and submarines together with large numbers of aircraft. The exercise was global in scale, with specific exercise areas including the Norwegian Sea, where simulated convoys were attacked; the northern and central Atlantic, particularly off the west coast of Ireland; the Baltic and Mediterranean seas; and the Indian and Pacific oceans. Overall, the exercise practised all phases of contemporary naval warfare, including the deployment and protection of SSBNs.

In 1976 an exercise started with a concentration of warships in the North Sea, following which they transited through the Skagerrak and into the Baltic. Although not an exercise as such, great excitement was caused among Western navies when the new aircraft carrier Kiev left the Black Sea and sailed through the Mediterranean before heading northward in a large arc, passing through the Iceland–Faroes gap and thence to Murmansk. NATO ships followed this transit very closely, as it gave them their first opportunity to see this large ship and its V/STOL aircraft.

The following year saw two exercises in European waters, the first of which was held in the area of the North Cape and the central Norwegian Sea. The second was much larger and consisted of two elements, one involving the Northern Fleet in the Barents Sea, while in the other ships sailed from the Baltic, north around the British Isles and then into the central Atlantic. Also in 1977 the Soviet navy suffered the second of its major peacetime surface disasters when the Kashin-class destroyer Orel (formerly Otvazhny) suffered a major explosion while in the Black Sea, followed by a fire which raged for five hours before the ship sank, taking virtually the entire crew to their deaths.

In 1978 the passage of another Kiev-class carrier enabled an air–sea exercise to take place to the south of the Iceland–Faroes gap. Similar exercises followed in 1979 and 1980. The 1981 exercise involved three groups and took place in the northern part of the Barents Sea.

There were no major naval exercises in 1982, but the following year saw the most ambitious global exercise yet, with concurrent and closely related activities in all the world’s oceans, involving not only warships, but also merchant and fishing vessels. In European waters, three aggressor groups assembled off southern Norway and then sailed northward to simulate an advancing NATO force; they were then intercepted and attacked by the major part of the Northern Fleet.

The major exercise in 1985 followed a similar pattern, with aggressor groups sailing northeastward off the Norwegian coast, to be attacked by a large Soviet defending task group which included Kirov, the lead-ship of a new class of battlecruiser, Sovremenny-class anti-surface destroyers and Udaloy-class anti-submarine destroyers, as well as many older ships. There was also substantial air activity, which included the use of Tu-26 Backfire bombers. Although not apparent at the time, this proved to be the zenith of Soviet naval activity, and in the remaining years of the Cold War the number and scale of the exercises steadily diminished.

These major exercises enabled the Soviet navy to rehearse its war plans and to demonstrate its increasing capability to other navies, particularly those in NATO. There were, of course, many smaller exercises, such as those involving amphibious capabilities, which took place on the northern shores of the Kola Peninsula, on the Baltic coast and in the Black Sea. It is noteworthy, however, that the vast majority of the exercises held in European waters, and particularly those held from 1978 onwards, while tactically offensive, were actually strategically defensive in nature, involving the Northern Fleet in defending the north Norwegian Sea, the Barents Sea and the area around Jan Mayen Island.

Soviet at-sea time was considerably less than that of the US and other major Western navies. The latter maintained about one-third of their ships at sea at all times, while only about 15 per cent of the Soviet navy was at sea, reducing to 10 per cent for submarines. The Soviets did, however, partially offset this by placing strong emphasis on a high degree of readiness in port and on the ability to get to sea quickly.