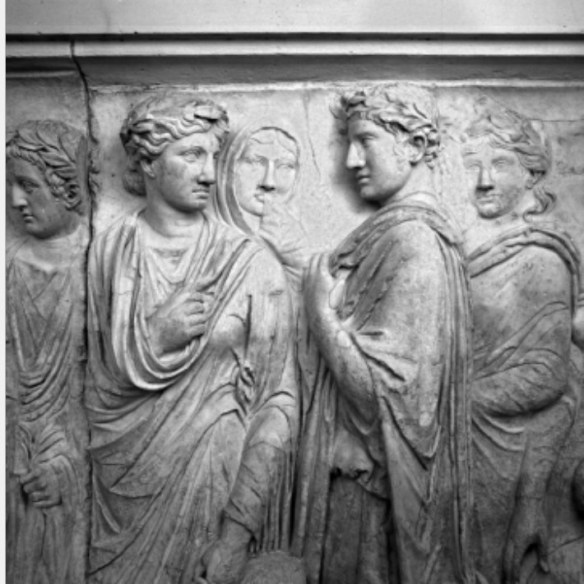

The only portrait of Drusus known to have been carved in his lifetime appears on the Ara Pacis in Rome. On the south facing enclosure wall, one figure in the procession is conspicuous by his attire. He is the only male figure shown wearing the paludamentum, the military cloak, in contrast to the others who wear togas; and caligae, the robust, open sandals worn by soldiers, which compare to the others who wear closed civilian boots. The consensus opinion is the figure is that of Nero Claudius Drusus since he was active on military campaign while the altar was being carved and at the time of the inauguration on 30 January 9 BCE. If the identification is correct, this is the only portrait of Drusus which can be securely dated to his lifetime. He is shown as a confident and relaxed individual in the company of his family. With her head turned to look at him is the figure of Antonia Minor, who holds the hand of a small boy identified as Ti. Claudius Nero (better known as Germanicus) who would have been nearly six years old at the time of the consecration ceremony.

Map of military operations in Magna Germania 10 BCE.

Map of the Roman Empire 16–9 BCE.

Roman Propraetor Decimus Claudius Drusus’ mind was on matters far from Rome. Perhaps inspired by the consuls of old or the lure of military glory, Drusus was intent on leaving the city at the earliest opportunity to continue the war.

He returned to Lugdunum in the spring of 10 BCE. The Tres Galliae continued to function as expected and there were no reports of unrest. His legates, meantime, had wasted no time in Germania. The Lippe River was now being lined with forts and logistics depots to relay supplies along the river delivered from Vetera. Work on Oberaden continued. A new supply depot to support the fortress was established a few kilometers downstream at Beckinghausen. Discovered in 1911 on a steep slope falling towards the river, it was subsequently excavated and an oval shaped encampment was uncovered measuring 185 meters (606.9 feet) by 88 metres (288.7 feet), encompassing an area of approximately 1.56 hectares, although the landing place for loading and unloading rivercraft has yet to be found. The main campaign this year would not, however, be driven along the Lippe River. Drusus now shifted the tactical thrust into Germania from a base further up the Rhine. A few weeks later he arrived with his entourage in Mogontiacum eager to launch an offensive to the Elbe via the River Main (Moenus or Menus). There were two legions at the camp, XIV Gemina and XVI Gallica. They may have been joined by vexillations of other legions from Fectio, Oppidum Ubiorum, Novaesium and Vetera. Detachments of these already made up at least two garrisons inside Germania. They would have been under orders to engage in simultaneous operations to drive deeper thrusts of their own into the territories building on the previous two campaign seasons; and to consolidate their gains with the construction of new forts, watch towers and roads. A skeleton crew would also have to be left at Mogontiacum (and the other Rhine fortresses) to guard it and manage the supply chain of provisions going to the front. Thus in practice the force for the new invasion along the Main River might have numbered as few as 10,000 men plus cohorts of auxiliaries.

A new fort may have been established at Frankfurt-am-Main-Höchst at the confluence of the Nidda and Main Rivers. As in the previous campaigns, Drusus used rivers to ferry much of the supplies his invading force needed by boat. The Main River is 524 kilometres (325.6 miles) long and a major tributary of the Rhine, with its source near Kulmbach, which is in turn fed by two minor tributaries the Red Main and White Main. The invasion plan was conceived with the usual Roman attention to detail, and logistics in particular. A supply depot was established at Rödgen near Bad Nauheim on the east bank of the Wetter River close by its source, about 60 kilometres (37.3 miles) east of the Rhine. It was polygonal in shape with a double ditch, 3 metres (9.8 feet) deep and wood-and-earth rampart structure 3 metres (9.8 feet) high and 3 metres (9.8 feet) wide at the base, enclosing an area of 3.3 hectares. Archaeologists found that the gateway, flanked by substantial towers, was wide enough for two wagons to pass through. These would have delivered corn and fresh produce brought up from Mogontiacum for storage in the warehouses and granaries inside the compound. There was also a well-equipped workshop. In the centre of the fortified camp was a principia, praetorium and barrack blocks sufficient for about 1,000 men but the size of the storage capacity meant it would feed many more mouths than its garrison. The nearby fort at Friedburg may have been connected with it.

The invasion route took them headlong into conflict with the Chatti who were a strong opponent. Unlike the previous campaign season, they had finally formed an alliance with the Sugambri and combined forces, having abandoned their own country, which the Romans had apparently given them. The Chatti were tough fighters and the ensuing conflict with the Romans was bloody and brutal. On the far northeastern edge of Chatti territory the Roman army established a major summer camp at Hedemünden near modern Göttingen, some 240 kilometres (149.1 miles) northest of Mogontiacum. Military surveyors laid out a narrow oval fortress taking full advantage of the Burgberg, a hill overlooking a bend on the Werra River, which is a tributary of the Weser. The defensive enclosure measured 320 metres (1,049.9 feet) long by 150 metres (492.1 feet) wide encompassing an area of 3.215 hectares. The 760 metre (2,493.4 feet) long circuit of wall measuring 5–6 metres (16.4–19.7 feet) at the base with a ditch outside was pierced by one gateway on each of the west and south sides, two on the east side with a curved but ungated northern end on the crest of the hill. There was an adjoining annex, also surrounded by a protective wall and ditch, which swept down to the riverside and may have been used for animals and supplies. The site, which has been partly excavated, has already produced over 1,500 iron objects carried by Roman troops, including exceptionally well preserved dolabra and pugiones, flat bladed spear points, the bent metal shank of a pilum, pyramid-shaped catapult bolts, nails, chain, hooks and even tent pegs with rings for tying the leather straps to. More personal items were also found such as iron hobnails – 600 in all – from caligae and a bronze phallic good luck charm. That the Romans were in the area on active campaign and taking prisoners is attested by an exquisitely nasty set of iron fetters. Shaped like the letter P the loop fitted around the neck and the hands were locked in two cuffs attached to the shaft. The short length of the shaft meant the captive wearer had to keep his arms up high across his chest – where they could be clearly seen by the guards – to avoid discomfort to the neck.

Anticipating his people might suffer a similar fate, one tribal leader took proactive steps to avoid conflict with the invaders. That year an enterprising noble from the Marcomanni nation named Marboduus or Marabodus, who was educated at Rome and once enjoyed Augustus’ patronage, returned to his people – or perhaps was taken there under Roman escort – and became their leader. He took back with him ideas about how the Marcomanni might introduce Roman-style law, government and military science. He had come to know the Romans well and understood what motivated them. Rather than challenge Rome or be subjugated by her, Marboduus decided upon a radical strategy. In a remarkable move, he convinced his tribe to relocate far from Roman temptation. Joining his people on the migration to a new homeland in Bohemia (Bohaemium) were the Lugii, Zumi, Butones (or Gutones), Mugilones and Sibini nations, a combined force of some 70,000 men on foot and 4,000 horse.

For those standing in Drusus’ path, the choice was ally with him or be prepared to fight. While the invading Roman army continued to attack and defeat any opposition as it progressed through the country, Drusus engaged in dazzling displays of single combat.

Waging war was a central defining characteristic of Roman culture. There was prestige and profit to be had in a successful campaign and to advance in politics meant showing courage and ability on the battlefield. Fifty-three years earlier Cicero had exhorted

preëminence in military skill excels all other virtues. It is this which has procured its name for the glory of the Roman people; it is this which has procured eternal glory for this city; it is this which has compelled the whole world to submit to our dominion; all domestic affairs, all these illustrious pursuits of ours, and our forensic renown, and our industry, are safe under the protection of military valour. The highest dignity is in those men who excel in military glory.

One way a commander could prove his worth was to engage his opponent in face-to-face combat, defeat him and strip his body bare of its arms, armour and personal effects. These rich spoils were called the spolia opima. They were then hung decoratively from an oak tree trunk as a trophy (tropaea) and the victor brought the display back to Rome and presented it as victor to the shrine of Iupiter Feretrius on the Capitoline Hill. Their exalted place in the Roman psyche was due to their extreme rarity. Legend had it that the first spoils were taken by Romulus from Acro, king of the Caeninenses in 752 BCE following the incident in which the Sabine women were raped. The second spolia were those of Lars Tolumnius, king of the Veientes, taken by A. Cornelius Crossus. The decaying linen cuirass and accompanying inscription were still in existence in Augustus’ time and they actually came to light during the renovation of the temple of Iupiter Feretrius at the request of the princeps.

The last recorded Roman commander to be recognised for wrenching the spoils from his fallen adversary was M. Claudius Marcellus (c.268–208 BCE). He was a distant relative of Drusus and as a child he would have heard the thrilling story, which is preserved by Plutarch, of how he captured them in 222 BCE.143 Day and night, the story went, Marcellus pursued the Gaesatae, a Gallic tribe, which had invaded the Lombardy region of northern Italy to assist their allies, the Insubres. He finally intercepted 10,000 of them at Clastidium. Unfortunately, Marcellus had with him just 600 lightly armed troops, as well as a contingent of heavy infantry and some cavalry. Viridomarus, king of the Insubres, thinking that his side had the advantage of greater numbers and proven skill in horsemanship, set out to squash the Roman invader without delay. The Gauls were now heading en masse at speed towards Marcellus’ forces. Fearing he would be overwhelmed, the consul deployed his men into longer, thinner lines with the cavalry placed at the wings. His own horse, however, was terrified by the ululations of the advancing Gauls and turned tail, carrying Marcellus back in the direction of the Roman lines. This did not look at all good in front of his own men, so thinking quickly on his feet, he made as if he was praying to the gods and promised to Iupiter Feretrius the choicest of the Gallic king’s weapons and armour. Meanwhile, Viridomarus standing in his war chariot and wearing his striped trousers had spotted Marcellus by the splendour of his kit and charged out to slay him. Seeing the gleaming silver and gold of the Gaul’s armour and the elaborate coloured fabrics of his tunic and cloak, and recalling his vow to the Roman god, Marcellus now charged atViridomarus.The adversaries raced closer and closer together. Marcellus saw an opportunity but he had to act quickly. With all his might, he hurled his spear. The slender iron tipped weapon sliced through the sky and found its prey. The blade pierced the Gallic king’s cuirass and the force of the impact thrust him off his chariot and crashing to the ground. Marcellus charged up on his steed and dismounted. With two or three stabs, Marcellus dispatched the man. He hacked off the dead man’s head, removed the torc from his severed neck in the manner of the Celts, and stripped the dead man of his splendid gear. Lifting them skywards Marcellus proclaimed,

“O Iupiter Feretrius, who observest the deeds of great warriors and generals in battle, I now call thee to witness, that I am the third Roman consul and general who have, with my own hands slain a general and a king! To thee I consecrate the most excellent spoils. Do thou grant us equal success in the prosecution of this war”.

The Roman cavalry then charged the Gallic horse and infantry and won a great victory, made all the more so on account of the small number of Marcellus’ force and the greater odds it faced. The Gaesatae withdrew and surrendered Mediolanum (Milan) and other cities under their control and sued for terms. The senate awarded Marcellus a triumph in which the spoils were prominently displayed to cheers from the spectators. The sight of Marcellus carrying the trophy adorned with Viridomarus’ spectacular armour to the temple of Iupiter Feretrius was “the most agreeable and most uncommon spectacle”, writes Plutarch. Some 175 years later a descendant of Marcellus who was a tresvir monetalis used his position to commemorate the event on a special denarius.

There was another ancestor on Drusus’ mother’s side whose story probably inspired the young commander to uncommon acts of bravery on the battlefield. That was the story of how his family acquired its cognomen Drusus. One of his ancestors had dueled a Gallic chieftain named Drausus and by killing him “procured for himself and his posterity” the name.

These tales of heroism and glorious deeds evidently left a deep impression on the young Claudian. The German War provided Drusus with numerous opportunities to win his own rich spoils. Suetonius remarks that he was eager for glory and “frequently marked out the German chiefs in the midst of their army, and encountered them in single combat, at the utmost hazard of his life”. Drusus may have been successful in his quest, “for besides his victories”, writes the biographer of the Caesars, “he gained from the enemy the spolia opima”. If indeed Drusus was successful – when and against which opponent is not recorded in the surviving accounts – this was an extraordinary honour. The last person to claim the honour was M. Licinius Crassus (the grandson of the triumvir) who had defeated an opponent in Macedonia in 29 BCE. His achievement was downplayed, however. Politics got in the way of him collecting his trophy. The honour was deemed too distracting to Octavianus’ efforts to consolidate his political power. Crassus was denied his eternal glory and fobbed off with a triumph. By the time Drusus had taken the rich spoils from his Germanic enemy Augustus’ power base was more solid and he could afford to allow his young stepson the public recognition. Indeed, it would have been first rate propaganda for here was a member of his own household who had achieved what only three other illustrious men had in the entire course of Roman history.

Postscript

Notwithstanding his grief at losing Drusus, Augustus was still intent on concluding the German War in Rome’s favour. Florus remarks that the Germanic nations were defeated but not yet subjugated, and that they respected the Romans’ moral qualities (mores) under Drusus’ rule more than they did Rome’s military might. It now fell to Tiberius to assume command of the Rhine army and in 8 BCE he departed for the front. Where Drusus had generally preferred the gladius to bring the German to his will, his older brother’s favoured weapon was diplomacy backed by the threat of force. It had served him well in Parthia and he evidently felt it would be worth trying again in Germania. Indeed, it was an insightful judgement. Hearing that Tiberius had mobilized his forces and crossed the Rhine, the nations living in the region bounded by the Ems, Lippe and Weser rivers sent emissaries to him to sue for peace. Initially absent, however, were the Sugambri. According to Dio, Augustus told Tiberius he would not accept terms from the Germans unless the Sugambri were part of the peace deal. The Romans and Sugambri embarked on a course of brinkmanship lasting several weeks. The Sugambri sent envoys who seemed unwilling to, or had been instructed not to, take the negotiations with the gravity the Romans expected. His patience tried, Tiberius had the Sugambrian delegation arrested, split up and distributed among the cities of Tres Galliae. The imprisoned ambassadors were very distressed by this unexpected turn of events and allegedly committed suicide (though that may have been cynical propaganda spin on a series of grubby behind-closed-doors executions). The stakes having now risen to the point where outright war might once again break out, the Sugambri finally returned prepared to negotiate terms. The result was a stunning U-turn by the Germanic nation that had for a generation led the offence against Rome. Tiberius’ calculated gamble had paid off. It provided timely propaganda the princeps needed for the audience at home. Displaying his talent for propaganda, Augustus states in his own memoirs that Maelo of the Sugambri was one of several named kings that “sent me supplications”. The terms offered to the Sugambri were different than those offered to the other nations. Like the Ubii before them, the Sugambri agreed to be relocated across the Rhine – Eutropius mentions 40,000 people – to the vicinity of Vetera where they became known as Ciberni, Cuberni or Cugerni, under the watchful eyes of the men of Legiones XVII and XVIII. Soon the Sugambri, like the Ligures, Raeti and Vindelici of the Alps before them, were supplying men for the Roman army. The cohors Sugambrorum quickly earned a reputation as a fierce fighting unit characterised by blood chilling war chanting and clashing of weapons before battle. Of the fate of Maelo the warchief, history is silent. Perhaps he settled in to a quiet life as a Romano-Germanic gentleman farmer, or he may have led one of the new military units under his own name and found adventure far from his new home.

For his victories, Augustus granted Tiberius the title of imperator and an equestrian triumph. He then took up his second term as consul with Cn. Calpurnius Piso. In his address to the senate on 1 January 7 BCE Tiberius set out his aspirations for the year and among them was the repair of the Temple of Concordia. Upon its entablature, he said, would be written a dedication from both himself and his brother Drusus. The session concluded, he rode his horse as triumphator along the via Sacra to the adulation of cheering crowds, enjoying a well-deserved occasion for public recognition, before ascending to the Temple of Iupiter Capitolinus for a feast with members of the senate.

Later that year he returned to Germania to deal with fresh disturbances there: despite the peace treaties of the previous year, the natives were ever restless. They rebelled again in 1 CE while L. Domitius Ahenobarbus – the first official legatus augusti pro praetore appointed by Augustus to provincia Germania – was campaigning. Ahenobarbus (‘bronze beard’) achieved what Drusus had not by crossing the Elbe River. He engaged the Hermunduri, whom he relocated to the region of Bohaemium in part of the territory already occupied by the Marcomanni. The Romans met no opposition from Marboduus’ people and even formed a “pact of friendship” with them. At the marketplace of the Ubii on the Rhine River Ahenobarbus set up an altar to Roma et Augustus, replicating the one Drusus had established at Lugdunum. The town changed its name from Oppidum Ubiorum to Ara Ubiorum to reflect its new status as a cult centre and Ahenobarbus also set up his provincial headquarters there. He attempted to negotiate for a number of hostages held by the Cherusci, but the involvement of other tribes as intermediaries resulted in failure and brought contempt for the Romans among the Germanic nations.

All was not well in the imperial household, however. Tiberius had thrown a fit for reasons scholars still debate and went into a self-imposed seven year exile to Rhodes. Only after a reconciliation with Augustus did Tiberius return again to deal with the situation in Germania in 4 CE. Sharing command of the campaign with Tiberius this time was G. Sentius Saturninus, the new legatus augusti pro praetore, who had been a legionary legate under Drusus.105 During the next two years, Oberaden was abandoned and the legions moved to new forward positions at Anreppen and Haltern and along the Lippe, while the unit that had been stationed at Dangstetten was subsequently moved to Oberhausen near Augsburg in 9 BCE, and transferred again to a new 37 hectare site at Marktbreit am Rhein in Bavaria eighteen years later. An amphibious campaign retraced the route taken by Drusus which took the fleet via the North Sea to the Elbe and sailed it upstream. Meanwhile, a land invasion led to the Cherusci, Chatti and others suing for peace terms. Under the energized force of Roman military might it seemed Germania Libera would finally bow to the Roman yoke. Indeed, the process of Romanisation of Germania had already begun. In large part due to Drusus’ explorations, the Romans had a much better understanding of the extent of Germania Magna and its peoples. Writing in the 80s and 90s CE Tacitus mentions forty tribes by name, almost five times the number recorded in Iulius Caesar’s Gallic War. Civilian settlements were being established. The remains at Waldgrimes in the Lahn valley discovered in 1993, complete with a basilica and forum dated using dendrochronology to 4 BCE, are proof of this.109 Other similar settlements may yet lie awaiting discovery by archaeologists.

In Rome Augustus’ carefully laid plans for succession had begun to unravel. In 2 CE Lucius died and three years later his brother Caius passed away. Faced with the prospect of dying without a successor, on 26 June 4 CE Augustus adopted both Tiberius and Agrippa Postumus (the youngest and only surviving son of Vipsanius Agrippa and Iulia). That same year, at the princeps’ request, Tiberius adopted Drusus’ eldest son, Germanicus, who was now 19 years’ old. In 5 or 6 CE, while Tiberius was waging war again over the Rhine, Germanicus and Claudius laid on gladiatorial games in honour of their father, to which the public responded with approval “for this mark of honour” feeling “comforted” by the recognition. In another public display of pietas for his brother, in 6 CE Tiberius dedicated the Temple of Castor and Pollux in his own name and that of Drusus, now dead since fifteen years. In the same year both Augustus and Tiberius were acclaimed imperator and the governor Sentius Saturninus was granted triumphal honours for brokering not one but two truces with the Germanic nations. In late 6 CE, Tiberius executed his own plan to take on the Marcomanni in their homeland of Bohaemium. It was the largest operation ever conducted by the Roman army, with at least twelve legions involved. However, hardly had they advanced north a rebellion in Pannonia – triggered by resentment at the punitive tribute levied on its peoples – stopped the massed army in its tracks and it had to be recalled. It would take three years of blood and treasure to quell the revolt. Taking part in suppressing that violent insurgency was a young noble of the Cherusci leading a Roman cavalry unit. He had received privileges directly from Augustus himself and assumed the name C. Iulius Arminius.

In 7 CE, Quinctilius Varus was appointed legatus augusti pro praetore of Germania. The son of the impoverished patrician family had done rather well for himself. In the complex world of political favours, Augustus tended to promote men from within his own family and social network. Varus was now married to Augustus’ great niece, Claudia Pulchra. Varus’ task was to pacify the region and transform it into a province. Perhaps he did the job too well. As the summer of 9 CE turned to autumn word reached Rome from Germania of a terrible disaster. At a place few Romans had ever heard of called saltus Teutoburgiensis reports came of a military catastrophe. Three legions – Legiones XVII, XVIII and XIX, all of them once under Drusus’ command – had been destroyed by a coalition of Germanic bandits. Incredibly the reports stated that the rebels had been led by C. Iulius Arminius, who was supposedly a trusted Roman ally. Cunningly he had used his position of status and trust to trick Varus and his intimate knowledge of Roman military doctrine to wipe out the governor’s army. As remarkably, it was a repeat of the same ambush tactic Drusus had suffered at Arbalo almost two decades before, except this time the Cherusci had not wavered and the Romans had lost. The Roman population panicked: barbarians were not supposed to be able to outwit them and now there was little between the Rhine and the Tiber to stop an invasion of Germanic hordes. Many recalled with terror the stories they had heard from grandparents about the Cimbri and Teutones. Where in this time of need was their Marius? A state of emergency was declared. Citizens were to be called up and given rudimentary training on the Campus Martius before being dispatched to Tres Galliae. When the appeal for volunteers went unheeded, Augustus drew men’s names by lot. When that failed to produce enough men he began ordering executions, and enlisted freedmen to the colours – a measure of how desperate the situation had become. It was then that he fired his German bodyguard. The feared invasion never came, but the trauma of the clades Variana remained for years. The few survivors from the three ambushed legions struggled back with tales of horror at the hands of blood-crazed Germani. That kind of talk was corrosive to public morale, decided Augustus: by edict, all survivors were banned from entering the Italian homeland for fear they would scare the local communities. The stain of shame would live with those men until their deaths. Augustus himself took the news personally and very badly. “Qinctilius Varus!” he was heard to cry as he tore at his hair and clothes, “give me back my legions!” It seemed his dream of a Roman Germania and beyond lay in tatters, yet Tiberius returned the following year and, with Germanicus’ support, after two years’ campaigning restored Roman control, at least along the river.

As his reign drew to a close, Augustus’ interest in annexing Germania waned and he attended to more modest enterprises. Before he died he is said to have made his successor promise not to overextend the boundaries of the empire: the Romans had their Lebensraum – let that be enough.