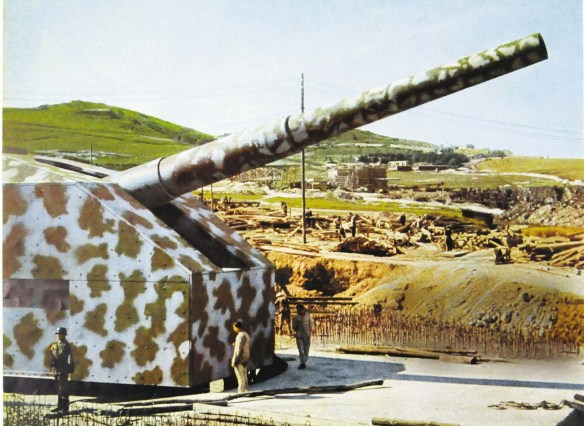

View of one of the 406mm naval guns while being installed at Battery Lindemann. The gun had a range of between 29 and 34 miles.

Photos from propaganda magazines showing Battery Lindemann under construction and completed.

Perspective view of Battery Lindemann.

Although the navy had its own construction units, this project was too large for them to handle. The OT had to deploy about 9,000 men to prepare positions for all the batteries in the Pas de Calais. Most of the batteries required for Operation Sealion initially occupied temporary firing positions until the concrete fortifications were ready to receive them.

Although the Kriegsmarine planned to position additional 380mm gun batteries along the Baltic after the summer of 1940, it gave the French coast higher priority in preparation for Operation Sealion. The new interest in the Baltic stemmed from the Soviet Union’s occupation of the three Baltic States in the summer of 1940, which gave the Red Fleet new bases outside the Gulf of Finland. The naval staff drew up plans for two batteries of 380mm guns, one to be sited on the Danish island of Bornholm and the other on the German coast near Kolberg to bar the Soviet fleet from the western end of the Baltic. Work began in November 1940 but had come to a stop by April 1941 as the site of the southern battery at Bornholm neared completion. The navy decided against emplacing any of the guns there and moved them to Hanstholm in Denmark, where work had also started back in November. The machinery and equipment went to Kristiansand in Norway, where another 380mm battery under construction was to join with Hanstholm to close the Skagerrak Straits. The largest guns were the 406mm (16-inch) pieces of Battery Schleswig-Holstein that the navy had installed at Hela on the Hel Peninsula in November 1940 to cover the approaches to Danzig. These were the ‘Adolph’ guns, intended for the 56,000-ton H-Class battleships. Organization Todt began the work late in 1940 and the site was ready for occupation by April 1941. The first gun’s test-firing took place in May, followed by the other two guns in June and October. The position included two munitions bunkers, a 23-metre-high fire-control position towering above the forest, and three large concrete emplacements for the turreted guns.

Not long after the invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, the Kriegsmarine bottled up the Red Fleet at the eastern end of the Gulf of Finland, reducing the need for the heavy battery positions in the Baltic. In September 1941 the naval high command (OKM) determined that Battery Schleswig-Holstein would be better employed in France, and by December the guns had been dis mantled and made ready for shipment to the West. The gun crews and other personnel did not leave Hela until April 1942, by which time the guns were already in France. The OT had begun the construction of the battery position in December 1941. The initial designation was Battery Grossdeutschland, but later in 1942 it was renamed Battery Lindemann in honour of Captain Ernst Lindemann, who went down with the Bismarck on 27 May 1941.

Construction for Battery Lindemann had to wait until the arrival of the guns from Hela in early 1942, since the casemates had to be built over the guns. These guns first fired in the summer of 1942.

Construction of a Battery Position

The construction time for a battery with concrete emplacements varied according to the size and type of gun position. A simple concrete platform that allowed the artillery piece to rotate from its fixed position took the least time to pour and cure and constituted the first construction step for a battery position. At this early stage the position also included concrete storage chambers for ammunition. This first stage took a relatively short time to complete. A gun casemate for an artillery piece with or without a shield or turret required much more time to put together. The casemates for the super-heavy artillery had to be built around the guns, which took even longer than for most gun positions. A large artillery piece to be emplaced on a large concrete bunker-like position with a turret or shield for protection took about the same length of time since the structure’s concrete roof had to be poured and cured sufficiently before the installation of the gun. A large gantry crane had to be brought to the site to emplace the guns and their turret before the construction of the casemate walls and roof.

Battery Lindemann, the largest in the Pas des Calais, is a good example. Work on its foundations began at the end of 1941, well before the first guns arrived. Once the guns were emplaced, work continued through 1942. The last gun positions were not ready until late spring 1942 and the first test-firings did not take place until June and July.

It took from six months to a year to get most of these batteries operational. Besides the firing positions, munitions bunkers, crew shelters and fire-control posts, other positions also had to be built to serve the battery.

The battery was operational by June 1942 and formally inaugurated in September. It consisted of three 406mm cannon each mounted in a turret within its own casemate. The walls of the upper level of the casemate were built around the gun turret. Each of these Regelbau S-262 gun casemates, identified as Anton, Bruno and Caesar, were large enough to contain quarters and facilities for the garrison, as well as munitions storage. Separate chambers in the magazine at the lower level held 600 rounds, powder charges and fuses. There was also a heating and air- conditioning room, an engine room and a filter room. The intermediate level and the upper level housed quarters for the garrison, the NCOs and officers, with showers, toilets and other facilities. A guard post covered the men’s entrance and on the opposite side another, larger entrance with a guardroom allowed access to munitions and supplies. At the end of the entrance an overhead monorail system carried shells to a hatch and lowered them to the magazine level. The roofs were thick enough to resist 380mm shells. The overall dimensions of the casemates were approximately 50 x 47 metres

In 1943 the OT completed ammunition magazines large enough for trucks to enter, as well as a hospital bunker. Wire obstacles and sentry posts surrounded the battery site. In addition, the battery was defended by 20mm Oerlikon and 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns captured from the British, two 75mm guns, several 25mm and 50mm anti-tank guns, a few mortars and several heavy machine-guns mounted in Tobruks. The thirty Tobruks were Bauform/Regelbau-58c intended for machine-guns. An additional Tobruk mounted one of the two 50mm anti-tank guns. Near the main gate leading to the town of Sangatte there was a Regelbau-655, a troop shelter with one chamber for six men, one for ammunition and an attached Tobruk. This bunker measured 10 x 10 metres. The battery formed a strongpoint manned by naval troops, but many of the bunkers were army designs. At the main gate there were two pre-fabricated concrete one-man sentry posts.

A large, two-level fire-direction S-100 Leitständ (fire-control) bunker served as the eyes of the battery guns. The OT built only four additional bunkers of this type in Norway and Denmark for the super-heavy 406mm gun batteries and for two other batteries. The Leitständ bunker housed an office for the battery commander and the bunker commandant. A rotating steel cupola mounted a 10-metre stereoscopic range-finder near the front of the block. In front of it was an observation cloche. A telephone and a radio room for receiving and relaying instructions were in this forward section, below the cloche and range-finder cupola. The operators in these rooms also received information from other observation positions. Behind these rooms there was a large computations room where about a dozen men tabulated the information and used plotting boards and charts to make the calculations for the firing orders that were sent to the gun casemates. Beyond this large room, near the entrance, were chambers for officers, NCOs and enlisted men. A ventilation room and an engine room to power the bunker and its equipment were located at the end of the bunker on either side of the entrance and gas lock. The lower level included quarters for the enlisted men with showers, toilets and a heating room. This large bunker measured 28.6 x 20.6 metres. Except for the positions on the roof, earth covered the exposed surfaces. The entrance at the rear was accessed from ground level by an incline.

One of the key instruments for locating targets was mounted on the roof of the S-100 bunker. This was the See-Riese FuMO 214 radar known as the Giant Würzburg (Würzburg-Riese) by the Allies. The Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine both used this type of radar. The one at Battery Lindemann was a naval version. The radar, like the cupola for the range-finder, stood above ground level, since this was the only way it could function properly.

The entire battery site occupied a position 500 to almost 1500 metres behind the coastal cliffs that rose over 20 metres above the beach. The coastal road ran between the cliffs and the battery position, which began on a small rise. Here stands the S-100 fire-control bunker with a view of the sea. The ground drops slightly behind this bunker for a few hundred metres and then begins to rise. This is where the three gun casemates were built. The ground rises behind the gun casemates, forming an escarpment. The small rise in front of the gun casemates and the escarpment behind them hides the bunkers from sight from the sea. Anti-aircraft guns and their facilities were located at the top of the escarpment.

The S-100 fire-control bunker was forward of the gun positions on a rise in the terrain that leads down to the sea cliffs across from the main coastal road. The battery and all its associated positions were surrounded by obstacles that included an anti-tank ditch and a wall along a few sections. The outer perimeter consisted of about 700 ‘Belgian Gates’ that were once part of a continuous anti-tank barrier south of Brussels extending towards the Meuse between Namur and Liege in 1939-1940. Barbed wire and minefields extended beyond the perimeter. Some minefields were actually inside the perimeter. An electrified wire fence surrounded each of the three gun casemates.

he battery complex also included a medical bunker, H-118, identified as the hospital. This bunker, measuring 22.2 x 12.8 metres, was smaller than the fire-control bunker but was large enough to house a couple of wards for patients, an operating room, a storage room and the quarters of the medical officer and his staff. Near this bunker stood the huts for the garrison, and a little further to the west were the two large ammunition bunkers. These two bunkers measured about 20 x 20 metres and were built into the terrain. Only the tunnel-like openings that ran in front of each bunker and the outer wall were exposed. On the south side of the position, near or at the top of the escarpment, two areas on either side of the anti-aircraft positions were encircled with double apron barbed wire obstacles. One of these areas included troop accommodation and entrances to a tunnel system that was never completed. The other area included two observation bunkers to assist in fire-control. Battery Lindemann and its associated close-combat defensive positions formed a strongpoint (StP) known as StP Neuss. Strongpoints like this or for smaller batteries often included covered brick-lined trenches that allowed the troops to move relatively safely from one point to another. This strongpoint was so heavily bombarded that it was difficult to determine if there had actually been covered trenches on the site. Other obstacles included steel hedgehogs, anti-tank ditches, etc. An anti-tank ditch ran along much of the east side, outside the perimeter made of Belgian Gates, and was backed by a concrete anti-tank wall up to 4 metres high. The medical bunker, the fire-control bunker and the three gun casemates were linked to a water line with a pumping station located between the gun casemates and the fire-control bunker.

Some features that show up on plans of Battery Lindemann but are often ignored are the hydrants. High-pressure water hydrants were distributed at various points at the large gun battery positions –and even the U-boat bunker complexes – for fire-fighting because fire extinguishers in the fortifications had limited capabilities. At complexes like Lindemann, special features like the hydrants, air-conditioning systems for cartridge rooms and power generating systems were necessary to operate the equipment effectively.

The other heavy battery positions were not much different from Battery Lindemann and were usually part of an StP. The engineers and artillerymen had laid out the batteries to meet the needs of the weapons available to them. As a result, except for the types of structure needed, no two batteries were identical. At Battery Lindemann and Battery Todt the large naval cannon were mounted in armoured turret types designated as Bettungsschiessgerüst C/39, but at Battery Grosser Kurfürst the 280mm gun was found in a single gun turret mounted on a large S-412 bunker. Like the Lindemann and Todt casemates, this bunker included all the facilities needed for munitions, the machinery and the crew. Batteries Fjell and Oerlandet in Norway were even more impressive than the ones in France. Their 280mm triple-gun turrets from the battlecruiser Gneisenau were mounted on an emplacement with a concreted shaft that connected to the magazines and a tunnel system below it. The shaft of Battery Fjell below the turret was 17 metres deep and consisted of six levels that were used for loading the weapon. Battery Vara at Kristiansand, Norway, had 380mm guns mounted in a turret on an emplacement that was part of a complex of four large single-level gun bunkers somewhat similar to the 305mm guns of Battery Mirus on the Channel Islands. The S-169 gun emplacement was actually adjacent to the bunker facilities and not on top of the bunker as at Battery Grosser Kurfürst. Since there was nothing below the gun position, this type was considered an open emplacement. One of these S-169 gun bunkers – only four of which were actually built – included a casemate over the gun turret.