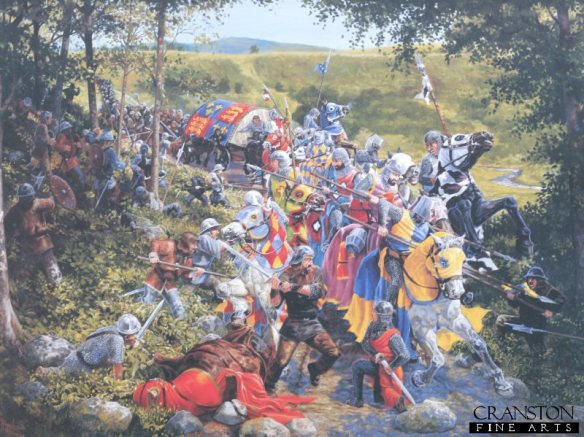

The Battle of Loudon Hill 1296 by Mike Shaw

In 1296 an English convoy escorting a shipment of looted gold was passing through the Irvine valley to the port of Ayr. It was led by an English Knight by the name of Fenwick, who in 1291 had killed the father of William Wallace, Sir Malcolm. Wallace, who was fighting a guerilla war on the English invaders, planned an attack at Loudon Hill where the road on which Fenwicks convoy was travelling had to pass through a steep gorge. Wallace had about fifty men and Fenwick close to one hundred and eighty. The Scots blocked the road with debris and attacked on foot. The English charged, but the Scots held firm. Fenwick armed with a spear, turned his horse in the direction of Wallace, who in turn felled Fenwicks horse with his claymore. The unhorsed Englishman was no match on the ground where he, along with one hundred of his convoy, met their deaths.

The status of the kingdom of Scotland constituted a key issue throughout the HUNDRED YEARS WAR. While seeking to overturn VALOIS overlordship in AQUITAINE, the PLANTAGENET kings of England sought also to secure their own overlordship in Scotland. The possibility that PHILIP VI would help the Scots resist English ambitions toward their kingdom was an important immediate cause of the war. The effective use that both France and Scotland made of one another in threatening England allowed the FRANCO-SCOTTISH ALLIANCE of the 1290s to persist throughout the war, and, on occasion, turned Scotland into a major theater of Anglo-French conflict.

Anglo-Scottish relations were largely peaceful until the 1290s, when a Scottish succession dispute allowed EDWARD I to pursue his ambition of ruling all Britain. Having recently brought Wales under his authority, he sought to do the same in Scotland. At the request of the Scots, Edward presided over the court that decided the succession question in favor of John Balliol. However, the new king’s authority was immediately undermined by Edward, who demanded that Balliol and his nobles perform military service in Aquitaine, and by the Bruces, Balliol’s chief rivals, who continued to contest the court’s decision. Balliol soon found himself at war with both Edward and the Bruces. In October 1295, a council of nobles acting in Balliol’s stead concluded an alliance with France, a compact that, through repeated renewals, lasted into the sixteenth century and became known in Scotland as the “Auld Alliance.” Unable to defeat his enemies, Balliol surrendered the kingdom to Edward in 1296, when many Scottish nobles renounced the French alliance and swore homage to the English king. However, a Scottish independence movement quickly emerged under William Wallace and others, who paved the way for Robert Bruce to be crowned king as Robert I in March 1306. The death of Edward I in 1307 and the military incompetence of EDWARD II allowed Robert to gradually expel the English from most of Scotland, especially following a decisive victory at Bannockburn in 1314. Although the pope placed Scotland under interdict at Edward’s request, the Scots in 1320 issued the Declaration of Arbroath, declaring their intention to continue resisting English domination.

In 1326, Robert renewed the French alliance. In 1328, the government of Queen Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer, earl of March, was forced to accept Scottish independence in the unpopular Treaty of Northampton. However, the death of Robert I in 1329 and EDWARD III’s overthrow of his mother’s regime in the following year revived the Anglo-Scottish wars. With his victory at HALIDON HILL in 1333, Edward forced DAVID II, Robert’s nine-year-old successor, to flee to France. The arrival of his Scottish ally persuaded Philip VI to demand that any Anglo-French settlement in Aquitaine also include the Scots. This requirement scuttled a proposed agreement and outraged Edward, who considered Scotland a purely English matter. When the Anglo-French conflict erupted in 1337, Edward declared French intervention in Scotland a major justification for his decision to go to war. Aided by the English preoccupation with France, the Scots, who proved themselves well able to maintain their independence without either a resident king or French troops, gradually drove out the English, allowing David to return in 1341. In 1346, David, upon hearing news of CRÉCY, invaded England in support of his ally. Defeated and captured at NEVILLE’S CROSS in October, David remained a prisoner until 1357, when he was released upon agreeing to a RANSOM of 100,000 marks. Having also agreed to cease fighting the English until the huge sum was paid in full, David in effect accepted an indefinite truce that limited active Scottish participation in the Anglo-French war for the rest of the century. Upon his accession in 1371, Robert II, first king of the House of Stewart, renewed the French alliance, as did his son, Robert III, shortly after his accession in 1390. Anglo- Scottish hostilities continued in the form of constant cross-border raids and contrary allegiances in the matter of the great papal schism, with Scotland recognizing Clement VII and England Urban VI. In 1406, internal disorder forced Robert III to send his young son and heir, James, to France, although the boy was captured by the English while crossing the Channel.

Upon Robert’s death shortly thereafter, his brother, Robert, duke of Albany, assumed the regency on behalf of his imprisoned nephew. After HENRY V invaded France in 1415, the Albany regime allowed more frequent border raiding to increase pressure on England in Henry’s absence. In 1419, the Scots responded to a plea from the dauphin for military assistance, and a large army was dispatched under John STEWART, earl of Buchan, who won a major victory at BAUGE’ in 1421. Rewarded with appointment as constable of France, Buchan persuaded other Scots to join French service, including Archibald DOUGLAS, earl of Douglas, who landed with an army of sixty-five hundred in 1424. Although Buchan, Douglas, and most of their men were slain at VERNEUIL in August 1424, many individual Scottish knights continued to serve CHARLES VII. Released in 1424 for a payment of 60,000 marks, James I renewed the French alliance in 1428 and agreed to dispatch a new army to the Continent in return for the county of Saintonge and the marriage of his daughter to Charles VII’s son. James’s murder in 1437 and internal disorder during the minority of his son, James II, prevented the Scots from playing a major role in the final campaigns of the Hundred Years War, although the Scots renewed the French alliance in 1448.

Further Reading: Curry, Anne. The Hundred Years War. 2nd ed. Houndmills, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003; Laidlaw, James, ed. The Auld Alliance: France and Scotland Over 700 Years. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 1999; Nicholson, Ranald. Scotland: The Later Middle Ages. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1974; Wood, Stephen. The Auld Alliance, Scotland and France: The Military Connection. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1989.