The second phase the fight for Katanga commenced with Security Council authorization to take “all appropriate measures” to prevent the occurrence of civil war in the Congo, including “the use of force, if necessary, in the last resort”. This resolution was used to justify UN military operations to end the Katangan secession. Ironically, Prime Minister Lumumba’s death triggered the fulfillment of his demands that the United Nations forcefully support his country’s campaign against the secession. Also looming large was the threat of intervention by the Soviet Union, which was emboldened and angered after Lumumba’s murder, and Moscow’s offer to provide the Congolese government with personnel and materiel to suppress the secession. These developments combined to mobilize Western powers to request the United Nations to fulfill that role.

Katanga’s leader, Moise Tshombé, professed anti-Communism and was backed by powerful Belgian and other Western interests, especially the company Union Miniere du Haute Katanga. Also Tshombé controlled Katanga’s gendarmerie and a large cadre of mercenaries. The resolve of his secessionists hardened after some 1,500 of the central government’s troops reached north Katanga in January 1961. Until that initiation of hostilities, the neutral zone negotiated by the United Nations with Tshombé on 17 October 1960 had held up but “it all came apart as pro-Lumumba troops captured Manono” in north Katanga. After Manono, the situation deteriorated rapidly and negotiations broke down.

On 28 August 1961, the United Nations launched Operation Rumpunch to arrest and deport mercenaries in Katanga. Then, in September, the Indian-led UN forces in Katanga launched Operation Morthor (“morthor” is the Hindi word for “smash”), to further round up foreign mercenaries and political advisers and to arrest Katangese officials. The “arrest” operation, which violated Hammarskjöld’s explicit directions to ONUC, quickly escalated into open warfare.

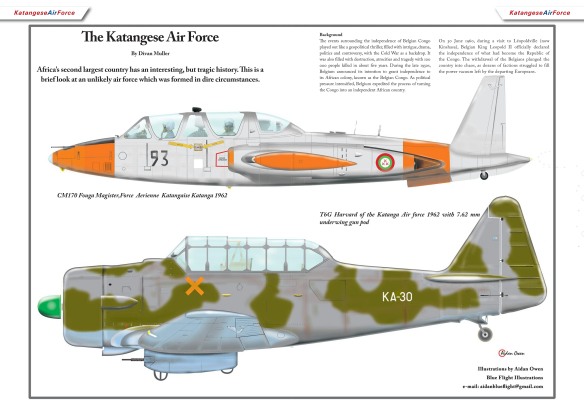

Almost immediately, air power in Katanga was brought in as a game-changer – but not by the United Nations. At this early stage of the conflict, the Aviation Katangaise (Avikat), also known as Force Aérienne Katangaise (FAK), held air superiority, though it consisted of only three Fouga Magister jet trainers. Remarkably, these aircraft were brought to Katanga in February aboard a Boeing Stratocruiser by the Seven Seas Charter Company, later identified as a US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) contractor and possibly a front company. After UN officials observed the unloading of the aircraft, the mission grounded the company’s entire fleet of planes, which the United Nations had earlier contracted to carry food. President John F. Kennedy decried the jet delivery and alleged in correspondence with President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana that the transaction had taken place before the US government could stop it.

In any case, the KAF fleet was quickly reduced in effectiveness: one Fouga Magister was lost when its pilot tried to fly under (rather than over) a power line; and UN forces captured another when they seized the airfield at Elisabethville, the Katangan capital, on 28 August 1961. This left the FAK with only one plane, but this single aircraft attained world renown during the hostilities of September by paralyzing UN supply efforts, which were mostly conducted by air transport aircraft. The single jet, flown by a Belgian mercenary from the Kolwezi airfield, also strafed UN positions, including the UN Headquarters in Katanga, and helped isolate a company of Irish troops who were forced to surrender to Katangan forces. Furthermore, the Fouga jet destroyed several UN-chartered aircraft at Katangan airports, including Elisabethville, the Katangan capital. A US State Department official, Wayne Fredericks, commented: “I have always believed in air power, but I never thought I’d see the day when one plane would stop the United States and the whole United Nations”.

Deadlock prevailed throughout 1961, and the indecisive outcome of the UN’s August and September 1961 ground initiatives in Katanga (Operations Rumpunch and Morthor) spurred Hammarskjöld to try to negotiate a ceasefire with Tshombé. As the Secretary-General was flying to meet with the Katangan leader at the border town of Ndola, Northern Rhodesia, his plane crashed on the night of 17 September 1961, killing all onboard. Complicating the rescue effort, the plane had largely maintained radio silence and flew a circuitous route mostly at night in order to reduce the possibility of an attack by the “Lone Ranger” Fouga Magister. The Katangan jet had shot bullets into UN aircraft only days before. And Hammarskjöld’s aircraft had been damaged by ground fire but was quickly repaired before take-off. The cause of the UN plane crash was never determined with certainty, though a UN commission concluded that it was probably due to pilot error during the approach to Ndola.

With Hammarskjöld’s death, the battle for Katanga entered a new phase. The new Secretary-General, U Thant, did not share Hammarskjöld’s belief that the United Nations should not interfere in Congolese internal politics. Moreover, the general escalation of events spurred the Security Council to pass Resolution 169 on 24 November 1961, strongly deprecating the secessionist activities of Katanga and authorizing ONUC to use “the requisite measure of force” to remove foreign mercenaries and “to take all necessary measures to prevent the entry or return of such elements”.

Meanwhile, the United States, fearful of communist encroachment on the continent, was resolved in the Congo to keep the Soviet Union out, the United Nations in, and Belgian interference down in the former colony. The Americans also wanted to stop the country from falling apart, viewing secession of mineral- rich Katanga as a threat to the economic vitality of the new country. In the background, decolonization was one of the great movements of the era and the United States was keen to show newly independent countries that it supported integral, viable new states. The disintegration of the Congo was a major concern, as was Soviet intervention. Therefore, international (United Nations) intervention in Katanga was deemed necessary, even if it meant intervention into the internal affairs of a new state (although at the request of that state). Thus the United States, which had previously refused Hammarskjöld’s requests to ferry troops within the Congo and had only brought troops to the Congo from abroad, now provided four transport planes without conditions. President Kennedy even offered to provide eight fighter jets if no other member nations were willing to do so. The US Joint Chiefs of Staff suggested these jets could “seek out and destroy, either on the ground or in the air, the Fouga Magister jets”. However, Thant sought to avoid direct superpower involvement in combat. Having promises of fighter jets from other nations, the American offer was turned down. Instead, the United States provided over 20 large transport planes to ferry reinforcements and anti-aircraft guns into Katanga.

Before his death, Hammarskjöld had managed to obtain from several UN member states promises of combat aircraft, which were desperately needed for the field mission. In October 1961, Sweden provided five J-29 Tunnan (“The Flying Barrel”) fighter jets. Ethiopia sent four F-86 Sabre jets, and India backed the mission with four Indian B(I)58 Canberra light bombers. These aircraft became what mission personnel dubbed the first “UN Air Force”.

The UN’s aerial assets soon joined the fray. In December, they attacked a military train east of Kolwezi and Katangan airfields at Jadotville and Kolwezi. The United Nations created havoc among Katangan forces in much the same way that the armed Fouga Magister had earlier done to the UN mission. Charanjit Singh, one of the Indian UN pilots, described his attack on a Katangan camp in Elisabethville on 8 December 1961 in a cavalier fashion:

…attacked an army police camp 2 km NE of old runway. Some vehicles were parked outside what looked like a headquarters building. I fired a full burst on those and saw them going up in smoke and flames. As I pulled out of the dive, I saw hundreds of men running out in utter panic. As I flashed past them, I gathered an image of men running in all directions, some in undies, others in halfpants, some in uniforms. I saw some enter a billet. Attacked the HQ building and vehicles again. Saw a vehicle turn over. At the end of four attacks, the whole thing looked like the Tilpat [air-to-ground practice firing range near Delhi] show.

The net result of the UN buildup and its December 1961 offensive was that Katanga’s “air superiority” was temporarily ended. The fate of the infamous jet trainer became an object of much speculation. The UN pilots claimed to have destroyed it on the ground in an air attack on the Kolwezi airfield, but they actually hit a carefully crafted dummy. It was then believed that the Katangan Fouga had crashed while its South African mercenary pilot had parachuted to safety, but this too was found to be false.

But even the UN’s new aerial hardware was deemed insufficient for the robust mandate. The UN field mission pressed headquarters to obtain bombs for the Indian Canberra jets. “We need those bombs”, Secretary-General U Thant would insist to the British government. After weeks of stalling, the government of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan finally agreed on 7 December 1961 to supply 24 1,000-lb bombs. But the offer came with the condition that they could only be used “against aircraft on the ground or [against] airstrips and airfields”. Even still, Macmillan worried that his government might fall over its handling of the Congo crisis, given the fierce support in some Conservative quarters for the anti-communist Katanga regime. In the end, the United States transported bombs directly from India.

Realizing what an enormous role a single Fouga jet had played in the success of Katangan operations in September 1961, Tshombé began purchasing new aircraft and hiring foreign mercenary pilots of various nationalities to fly them. Indeed, throughout 1962, UN Air Command desperately tried to monitor the Katangan aerial buildup through both aerial surveillance of Katangan airfields and intelligence gathered by ONUC’s Military Information Branch (MIB). In an attempt to procure immediate intelligence on Katanga’s air capability, a desperate ONUC on 9 March 1962 noted that aircrews from UN military air units and from its charter companies were making “important observations during their flights and stops at various airfields in the Congo”. The mission began mandatory debriefings of aircrews after landing. The mission also sought to create an air reconnaissance unit capable of meeting both long-term reconnaissance and immediate operational requirements. One memo dated 10 March 1962 stated “it becomes imperative that the air recce unit should be allotted with both C-47s and jet recce aircraft such as S-29s or photo-recce Canberras”. ONUC’s Chief of Military Intelligence requested three C-47 aircraft “to check the Katangan air movements through systematic visual reconnaissance of their airfields”. On 6 June 1962 the ONUC Force Commander cabled Ralph Bunche, the Under-Secretary-General at UN Headquarters responsible for peacekeeping operations that:

ONUC suffers from a grave lack of reconnaissance facilities. As a result even the photographs available may contain much more information which it is NOT possible to get because of inadequate facilities in equipment and personnel for interpretation.

In 1962, Sweden provided two J-29Cs, the photo-reconnaissance versions of the J-29 jet aircraft that proved of great worth. The mission consequently added personnel designated as air intelligence officers. At the same time, the threat of re-emerging Katangan aerial capabilities was real. ONUC concluded in May 1962:

[M]ercenaries, fighting for money and receiving higher salaries as FAK pilots than even Generals receive in UN service, are ruthless, cunning, non- conventional, clever and inventive. They have war experience, and they know where, when and how to hit. there is no alternative but to consider FAK as a dangerous enemy in the air.

ONUC had success uncovering the extent of Tshombé’s aircraft acquisitions through intelligence gathered by the MIB. Defectors and informants interviewed by the MIB revealed a wealth of information about Katangan aircraft both in Katanga and neighbouring countries. Lieutenant-General Kebbede Guebre (Ethiopia), the ONUC Force Commander, cabled Bunche at UN Headquarters on 24 August 1962, referencing a report that Katanga-owned jet fighters were hidden in Angola and/or Rhodesia. Kebbede requested Bunche to “check with Australia [about] the possibility of Australian trained jet [mercenary] pilots being available to Tshombe”. In another cable to Bunche dated 27 September 1962, he stated that:

a fully reliable source reported…that twelve Harvard aircraft have recently left South Africa, bound for Katanga…equipped with guns and French rockets…[and that] an unspecified number of P-51 Mustangs may have left South Africa recently…intended for Katanga.

Clearly, the United Nations perceived itself in an aerial arms race with the Katanga government. It was trying to persuade its member states to provide aircraft while the Katanga government was purchasing them clandestinely wherever possible.

General Kebbede again cabled Under-Secretary-General Bunche on 1 October 1962, comparing the air capabilities of the two protagonists. Katanga (FAK) was now estimated to have twelve Harvard single-propeller aircraft, eight or nine Fouga Magister trainer jets, four Vampire jet fighters and a large number of P-51 Mustang single-propeller fighters (being delivered). The UN mission possessed six Canberra jet fighter-bombers, four Saab J-29B fighter-bombers, and four Sabre F-86 jet fighters. At the time, the UN Air Division possessed no bombs – a serious deficiency, as it was considered the weapon needed to neutralize air bases and enemy forces on the ground. Great Britain was still dithering on UN pleas for bombs for its Canberra aircraft. ONUC concluded once again that air resources were inadequate to meet the FAK threat. Due to serviceability problems, only about 60 to 70 percent of ONUC aircraft would be available for operations, which would make it impossible to keep even a section of fighters on readiness and thus impossible to simultaneously defend even one airfield, conduct offensive sweeps, and escort transport aircraft. Moreover, since ONUC was entirely dependent on supplies delivered by air, of which 95 percent were lifted by civil chartered companies, a Katangan air threat would ground essential supply planes in the absence of UN fighter escorts.

In the same October 1962 report to Bunche, General Kebbede recommended immediate steps be taken to reinforce the UN Air Division. The first recommendation was for the acquisition of two S-29E photo-reconnaissance aircraft and a complete photo-interpretation unit to monitor developments and activities at Katangan air bases. The second was to increase two UN fighter squadrons to eight fighters each (for a total of 16 fighters). The third was the addition of two additional Canberra aircraft. Also recommended was the acquisition of anti-aircraft defences for UN air bases and radar for Elisabethville, as well as heavy-calibre and napalm bombs for the Canberra bombers and additional communications equipment. These recommendations were considered to be the bare minimum necessary for the operation.

Things became even worse when Ethiopia abruptly withdrew its Sabre aircraft after losing one in an accident. Furthermore, India experienced an urgent need to repatriate its Canberra bombers to fight in a border war with China. On the positive side, Sweden promised more Saab jets and Norway offered an anti-aircraft battery. New air surveillance radars were deployed at Kamina and Elisabethville.

A few days following Kebbede’s UN requests, a cable from Robert Gardiner, the UN representative in the Congo, to Bunche reported that a South African aircraft company had offered Katanga 40 Harvard aircraft, each equipped with 40 rockets, for US$27,000 each. The planes were thought to be transported into Katanga through Angola, a Portuguese colony. Moreover, intelligence reported that the same company had previously sold 17 aircraft to Katanga. On 17 October, Gardiner cabled Bunche that aerial photography had confirmed the presence of six Harvard aircraft at Katanga’s Kolwezi-Kengere airfield.

The UN mission was clamouring to increase its air force, particularly its fighter strength, despite UN Headquarters’ concerns about costs, having overcome earlier inhibitions on combat. Intelligence evidence mounted regarding the acquisition of new aircraft by Katanga. The growing strength of Katanga’s air force relative to ONUC’s had immediate military and strategic consequences. The ANC were frequently bombed and harassed by Katangan aircraft. The UN Commander’s assessment was that:

Due to ONUC’s limited strength of four fighters, we have to confine our action to Recce the area in question as often as possible during daylight and attack any Katangese aircraft flying in that area. We are not attempting to destroy any aircraft found in the airfield in the vicinity of that area because if we do locate one or two aircraft and destroy them, we feel that FAK will react against [our] Kamina Base and also disperse their aircraft from Kolwezi to other airfields, thereby making our task of locating and destroying these aircraft on the ground very difficult. Please advise dates by which additional four Swedish fighters, as promised, will be available and if any additional aircraft expected from other nations.

The UN Commander’s strategy was to wait until the new aircraft gave ONUC a fighter force capable of destroying the bulk of Katanga’s air force on the ground in one overwhelming surprise attack. Another cable from Kebbede to Bunche on the same day (24 November 1962) stated that:

on request from the ANC, air recce missions over Kongolo area are being provided by UN fighters. Missions will be confined to recce and destroying any Katangese aircraft if found flying over that area. Instructions have been issued NO repeat NO ground targets to be attacked.

The ONUC Commander did not want to give the Katangese any reason to disperse or hide their aircraft but rather wanted them to feel that they were safe and secure when on the ground at their major airfields.

Air Power in UN Operations (Military Strategy and Operational Art)

A. Walter Dorn is Professor of Defence Studies at the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) and chair of the Department of Security and International Affairs at the Canadian Forces College (CFC). As an ‘operational professor’, he has visited many UN missions and gained direct experience in field missions. He has served in Ethiopia as a UNDP consultant, at UN headquarters as a training adviser and as a consultant with the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. He has provided guidance to the UN on introducing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to the Eastern Congo.

I welcome this unique volume on air power in UN operations. It provides a close look at the ways peacekeeping and enforcement can be facilitated from the air. It provides an impressive and wide-ranging examination of air power applications from the past and points to how these can be made more effective in the future. –Lieutenant-General The Hon. Roméo A. Dallaire (retired)

Combining rigorous analysis with compelling

first-hand experience, and awareness of new technologies with deft

appreciation of history, this book provides a compelling account of the

use of air power in UN operations which provides both rich insight into

its possibilities and frank advice about its limitations and management.

Comprehensive and authoritative, it will be core reading for analysts

and practitioners alike for years to come. –Alex J. Bellamy, Griffith

University, Australia and International Peace Institute

Since

1945 when the United Nations was created in San Francisco, nations often

look to this international organization to keep or restore global

peace. Professor Walter Dorn’s outstanding anthology provides a much

needed examination of the UN’s air power capabilities for global

intervention to halt war-fighting. He and his expert colleagues address,

lucidly and with fresh insights, several case studies in which UN air

power has played a role in peacekeeping; they examine such key questions

as how and under what circumstances the UN has used air power, as well

as the strengths and weaknesses of this approach. –Loch K. Johnson,

University of Georgia, USA