This revolt should have been foreseen. The Druze had soon found that the autonomy the French granted them was, in reality, largely a way for the French to interfere in their lives, manipulate disputes between Druze notables to their advantage, and extend their control into the Druze heartland. They were well aware of the French “divide and rule” policies, and observed how they were calculated to insulate the Druze heartland from Damascus, which they resented. They felt much closer to other Syrians than the French were prepared to admit to themselves. Druze leaders such as Sultan al-Atrash had contact with Damascus- based nationalists as well as those in Amman, the capital of Jordan. When their revolt came, it was in the name of Syrian independence – not that of the Druze state-let which the French had carved out for them.

The Hawran had already been restive and seen much discontent, but the straw which broke the camel’s back concerned the behaviour of a Captain Carbillet who had been temporarily put in charge of the Druze state-let while the French decided whom to appoint as the next ethnically Druze governor. Appointment of the governor was a delicate question for the authorities, since it meant successfully negotiating their way through the maze of Druze clan politics. Carbillet was a high- minded but arrogant believer in the values of the French republic. He was energetically trying to bring the modern world to the Hawran, and enjoyed High Commissioner Sarrail’s full support. But his decision to split common land between peasant families as part of a land reform programme – aimed at ending what he perceived to be “feudalism” – conflicted with customary usages. This made him unpopular, as did his conscription of Druze from all segments of society as forced labour to build roads. Not only did the Druze object to the forced labour on principle, but they considered conscripting their clan leaders an insult to the clan. They also shrewdly observed that the main purpose for the roads would be to bring tax collectors and the French army to their doors.

On 11 July, three Druze leaders arrived in Damascus at Sarrail’s invitation to discuss their grievances, while Carbillet had been sent on temporary leave. Sarrail decided to hold them hostage to encourage “good behaviour” among the Druze, and had them taken to Palmyra and imprisoned. This was understandably seen as an appalling breach of the traditions of hospitality and treatment of envoys. A week later, the Hawran rose under the leadership of Sultan al-Atrash, the most important Druze clan leader and an eminent notable whose father had been hanged by the Turks. Although an officer in the Ottoman army, by the end of the Great War he had become a firm partisan of Faisal and the Arab revolt. More recently, he had his own cause for concern as the French had been trying to undermine his pre-eminent position among the Druze.

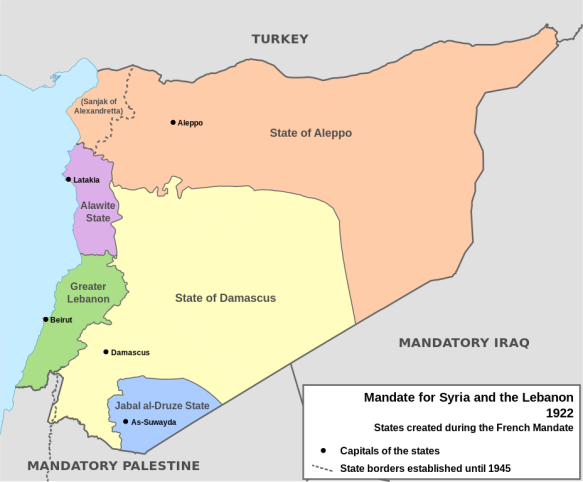

French columns in the Hawran were ambushed and destroyed, and then a punitive expedition sent from Damascus was forced to retreat. During the first weeks of the rebellion, a thousand French colonial soldiers were killed, and the Druze even captured some artillery. Their revolt soon spread beyond their community, as some local Muslims and Christians joined in. A Druze column marching on Damascus was only stopped outside the city in late August by an air attack and a Moroccan cavalry squadron. Leaflets signed by Sultan al-Atrash appeared in many neighbourhoods. They combined Arabic rhetoric with that of the French Revolution, and clearly demonstrated that intellectuals in Damascus had had a hand in drafting them. They denounced the French attempts to divide Syria – as well as the partition of Greater Syria itself:

The imperialists have stolen what is yours. They have laid hands on the very sources of your wealth and raised barriers and divid- ed your homeland. They have separated the nation into religious sects and states. They have strangled freedom of religion, thought, conscience, speech and action. We are no longer allowed to move about freely in our own country.

They ended with four demands:

- The complete independence of Arab Syria, one and indivisible, sea coast and interior;

- The institution of a Popular Government and the free election of a Constituent Assembly for the framing of an Organic Law;

- The evacuation of the foreign army of occupation and the creation of a national army for the maintenance of security;

- The application of the principles of the French Revolution and the Rights of Man.

To arms! God is with us. Long live independent Syria! Sultan al-Atrash, Commander of the Syrian Revolutionary Armies

Within days, the countryside around Damascus had ceased to be secure territory for the Mandate forces. The French clamped down in Damascus itself, arresting such leading lights of the People’s Party as they could find, but many had escaped, including Dr Shahbandar who fled to the Hawran where he attempted to establish a provisional rebel government on 9 September. With the help of reinforcements, the French tried to stamp out the source of the rebellion. At first the army successfully penetrated the Hawran, inflicted a bloody defeat on the Druze and relieved the French garrison at Suwayda which had been besieged in the citadel. But then it had to withdraw because of its supply situation. For the Druze, defeat was turned into victory.

This was the point at which the revolt spread in a major way. On 4 October, the Syrian troops in Hama mutinied under the leadership of Fawzi al-Qawuqji, a survivor of the Syrian forces at the battle of Maysaloun. He had joined the army of the French Mandate and was now a captain in a cavalry unit. The Hama uprising had been carefully timed, and Qawuqji waited until most of the garrison had been transferred to reinforce the French in the Hawran. Rapidly taking control of the city, he besieged the remaining French in their headquarters. The authorities, however, hit back by sending their air force to bomb Hama into submission. Local notables persuaded Qawuqji and his followers to leave so as to avoid further destruction, but the insurgents took refuge in the surrounding countryside and waged guerrilla war against French communications.

The French also lost control of the Ghouta, the countryside around Damascus, and insurgent bands also began to appear in many other parts of Syria. Counter-attacks against the insurgency were frequently ineffectual, so the authorities resorted to reprisals and collective punishments. The French recruited gangs from the Circassian and Armenian minorities to carry out their dirty work. It was a sign of how nervous they were becoming about trusting Arabic-speaking Syrians. Villages, including the Druze settlement of Jaramana just outside Damascus, were systematically destroyed, and prisoners shot. On one occasion, the authorities executed up to 100 inhabitants of villages in the Ghouta, and brought a further sixteen young men back to Damascus to be shot in the central Marja square, where the bodies were left on public display. After this incident, the French had an unpleasant surprise a few days later. The corpses of a dozen captured Circassian militiamen were discovered lying near Bab Sharqi, the eastern gate of the city. The hands of the rebels were far from clean.

Insurgent bands engaged in extortion to finance and supply the revolt. They also attacked villages which refused to cooperate, and cases of naked brigandage occurred.

On 18 October the rebels took control of most of Damascus, burning and looting much of the sprawling Azm Palace, the governor’s residence, where they had hoped to capture General Sarrail. They also slaughtered Armenian refugees who had fled from Turkey, and were now encamped to the south of the city at Qadam. These refugees were alleged to have been members of militias which had taken part in massacres in the Ghouta. Police and gendarmes melted away from their posts, and French armoured cars were reduced to firing blindly as they passed through the streets, terrorising but failing to hold neighbourhoods. Many people from the Christian and Jewish quarters had participated in a big nationalist demonstration which had taken place during the Muslim religious celebrations for the Prophet’s birthday a few weeks earlier. All districts of the city were now backing the insurgency, but the rebels took special care to reassure and safeguard the Christians and Jews as they moved through Damascus. This prompted an ironic comment by W. A. Smart, the British consul, in a report to his superiors: “These Moslem interventions assured the Christian quarters against pillage. In other words it was Islam and not the `Protectrice des Chrétiens en Orient’ which protected the Christians in those critical days.” This incident illustrates that, contrary to what the French tended to feel instinctively, the nationalism they were encountering did not fit the label of the “Muslim fanaticism” which they constantly attempted to pin on those who opposed them. Their obsession with seeing Arab nationalism through this particular prism made it very hard for them to understand it, let alone come to terms with it.

Now the French did as they had done in Hama, with equal success but greater violence, even though the protests their actions caused led to the recall of Sarrail. For two days, they shelled Damascus, leaving much of it in ruins and on fire. One area was so thoroughly destroyed that when it was rebuilt the original street pattern was abandoned. It also acquired a new name, “Hariqah”, meaning “Fire”. One thousand five hundred people are estimated to have been killed in the bombard- ment (in Hama, the inhabitants had claimed the death total was 344, mostly civilian – the French admitted to 76, all of them insurgents). As in Hama, a delegation of notables persuaded the rebels to leave the city. The delegation also agreed to pay the authorities a hefty fine in exchange for ending the bombardment.

Once again, the rebels were forced out of the urban areas into the suburbs such as Maydan and the surrounding belts of farmland, where they disrupted French communications with, for a time, increasing success. That winter, the rail link into Damascus was regularly cut by the activities of co-ordinated bands of insurgents who now dominated virtually the whole of the southern half of Syria. The French air force conducted what may well have been the most intensive and systematic aerial bombardments against a civilian population that had taken place up to that time anywhere in the world, as their planes returned to bomb villages on a daily basis. The intention of the bombardments was to punish and deter, but initially it bred hatred and made its victims flock to join the rebels. Maydan suffered repeated assaults because of its obstinacy, and was cut in half by a new road and barbed wire as the French built a security barrier round the city.

The final French assault on Maydan in May 1926 was savage and brutal. One thousand houses and shops were destroyed by incendiary bombs dropped by the air force and up to 1000 people were killed – many of whom were women and children and only about fifty were fighters. A neighbourhood where 30,000 people had lived was now a desolate ruin. But the onslaught achieved its objective. On 17 May, lights shone again from the minarets in the city, something that had not been seen for months. Refugees from Maydan now thronged into the Old City to join those from the Ghouta, the Hawran and other areas. The French did little to help them. It has been suggested that this was deliberate. The French “relied on the growing state of misery, which they attributed to the rebellion, to force the rebels and their supporters into submission”.

The Maronites of Mount Lebanon and many other Uniates generally supported the French, but many Orthodox Christians backed or joined the rebels. In some Christian communities, such as the small towns of Ma’loula and Saydnaya, the Christians may have split more or less on sectarian lines between Uniates and Orthodox. The ancient Orthodox convent of Saydnaya tended wounded rebels and collected food for the fighters. At least one letter has survived from the leader of a rebel band to an Orthodox notable in Damascus asking him to provide young men from his community to fight in the insurgency. There were also areas, such as Aleppo, where there was nationalist agitation but no explosion of revolt, even though on one occasion Moroccan cavalrymen dispersed a demonstration in the city and killed at least fifteen people with their sabres. The Alawi area was also quiet. This may have reflected its relative isolation compared with the Hawran. The Alawis had no equivalent to the longstanding corn trade links with Damascus which had hampered the French attempt to separate the Druze from the rest of Syria.

Minor rural and provincial notables like Sultan al-Atrash and Fawzi al-Qawuqji, who were often former Ottoman army officers, provided most of the military leadership for the revolt. Many city notables with large rural estates supplied the revolt with arms, money and men, and it was also widely supported by urban merchants, particularly the Damascus grain merchants of Maydan and Shaghur. Much of the rank and file were peasants, those who had left the land and were destitute because they could no longer make a living there, and the urban poor. Economic factors, including drought, also played their part in boosting recruitment. The rebels had more support and sympathy among the young than the old, and there were elements of what might be called class struggle in the demands sometimes made of leading notables to provide funds, men and other support. Among the wealthier sections of society, many people sat uncomfortably on the sidelines, and more than a few were quietly relieved when the revolt was crushed.

Sometimes, but not always, there was a religious tinge to the revolt: the use of traditional Muslim warrior rhetoric and appeals for jihad against the unbelieving French. For the French to rule a predominantly Muslim country was, in the eyes of Syria’s Muslim majority, a scandal of monumental proportions. Fawzi al-Qawuqji exploited this fully in Hama where, before the revolt began, he had founded his own political party known as Hizbullah, or “the Party of God”, to appeal to the conservative Sunni population of the city. He also grew a beard to mark himself out as a devout Muslim, and spent many evenings in mosques where he encouraged preachers to support him and give sermons on jihad.

For obvious reasons, neither class warfare nor this populist/religious current chimed well with the elite nationalists. When Dr Shahbandar proclaimed a provisional government, he used purely secular language in his communiqué. Yet it would be wrong to see the nationalism of the elite as entirely secular. Because they saw themselves as the leaders of Syria, they considered that they should represent its people. The religious rhetoric of Islam has its place in any sense of Arab pride, and was an obvious rallying cry. Ordinary people felt their customs, their way of life and their religion were under attack from alien forces. The nationalist elite shared this perception, and it was only natural for it to use religious symbolism on appropriate occasions. Nor did this lead to a neat sectarian divide. In 1923, right at the start of the Mandate, Yusuf al-`Issa, a Christian, had suggested in the Damascus newspaper he edited that “the birthday of the Arab prophet” should be made a national holiday. He saw it as a way to unite all the “communities” that speak Arabic – the entire Arabic-speaking nation.

By the summer of 1927, France had succeeded in crushing the revolt. This would have been impossible without large numbers of additional colonial troops who were brought in from Algeria, Senegal and Madagascar. A significant role was also played by the badly disciplined militias. These were particularly important in the earlier stages of the rebellion when they were short of troops. As the French regained territory and maintained their grip on it, the heart went out of the rebellion. In October 1926, Sultan al-Atrash and Dr Shahbandar took refuge in Jordan. Fawzi al-Qawuqji fought on into the following spring, by which time he and his followers could no longer find the welcome and support from the local population which they would once have received. State terror had done its work. By the very end, more than 6,000 rebel fighters had been killed and 100,000 people – a staggering number in the Syria of the mid-1920s – had seen their homes destroyed.