Channel Islands

During the report on the successful raid on the port of Granville by the forces stationed on the Channel Islands, the Commander-in-Chief, Navy, states that the newly-appointed commander of the Channel Islands, Vice-Admiral Hueffmeier, is the heart and soul of this vigorous action.

These were brave words, but with the benefit of the hindsight of history, in Outpost of Occupation, Barry Turner puts the raid in context:

The Granville raid was audacious and bravely executed but it achieved little of substance, except to provide the Channel islands with an extra delivery of coal. It made no contribution to the German attempt to hold the Allies at its borders until a peace deal had been brokered, and while a boost to garrison morale was badly needed, there is no suggestion that it won over any of those who doubted Hüffmeier’s sanity.

In Berlin, another man with a limited grasp on reality, William Joyce, ‘Lord Haw Haw’, speaking of the Granville raid in a broadcast on 9 April 1945, said, ‘The BBC is compelled to admire the strength of the German resistance in the West.’

In reality, though the raid had been audacious it did not cause a significant amount of damage to shipping or the port installations.

The 1,049-ton SS Parkwood had one boiler destroyed and a hole blown in her starboard side. The little 927-ton SS Nephrite had a boiler destroyed and a mine detonated in the fiddley (the hatch around the smokestack and uptake on the weather deck of a ship for ventilation of the boiler room) and No. 2 hatch.

The 845-ton SS Kyle Castle had charges detonated in the engine room and the hull was holed below the waterline. Capt. William Fraser, the master of the Kyle Castle, a tough 46-year-old Ulsterman who had joined the merchant navy at the age of 16, had refused to co-operate with the raiders and had been killed. Richard Reed hid along with another member of the crew until the Germans retired and then he took over as captain. He managed to repair the damaged hull, but with engines unusable, he then floated Kyle Castle out on the ebb tide and, with the hatch covers as improvised sails, managed to make the Channel and was then towed into Plymouth. Capt. Fraser, who along with the other casualties of the raid is buried at Bayeux, had been awarded the MBE in 1944 for gallant and meritorious service.

Lastly, the SS Heinen had suffered the modest damage of a bullet hole through the wheelhouse window. Significantly, only two days after the raid, three of the four damaged ships were operable again.

In the port, of the five portal cranes on the North Quay, Nos 1, 2 and 3 were repaired in a day; No. 4 was, however, badly damaged, but No. 5 was operable. Of the six portal cranes on the South Quay, No. 1 was repaired in a day, though Nos 2 to 6 were badly damaged. Of the six crawler cranes, three were seriously damaged, whilst three could still be operated. One 22-ton Kearing crane was badly damaged. Three stiff leg derricks were listed as being in ‘fair working condition’, while one shunting locomotive was destroyed and the raiders destroyed a US Navy Jeep when they threw a grenade into the vehicle.

Hüffmeier would assert after the war that there was additional damage, including an ammunition bunker and eight trucks destroyed. The American report on the raid makes no mention of this damage, and moreover states that the port was back in action within two days of the raid, albeit at a reduced capacity. However, the Americans conceded that ‘the enemy had fire superiority … which enabled him to set off demolitions at will … In fact he had complete control of the Granvillle area and were his objective that of conquest, he was the conqueror.’

There would be one more raid from the Channel Islands, on 5 April 1945, when an eighteen-man German sabotage squad sailed from Jersey via Alderney in the vessel M4613. The M4613 was a drifter that had been modified as a minesweeper and consequently could have been mistaken by the Allies for a French fishing boat.

The raiders’ mission was to disrupt the rail links from Cherbourg by blowing up the bridge at Le Pont. The team was named the ‘Maltzahn Demolition Party’ after Lt Maltzahn, the officer who had trained the men and would lead them on the operation. Though the sabotage team was drawn from engineers in the army garrison of the islands, it had a Kriegsmarine signaller, Funkergefreiter Bernd Westhoff, attached – dressed in army uniform. Each man carried his personal weapon and ammunition, rations and 16kg of explosives.

Westhoff had a simple code with short signals that began with the message that, decoded, read ‘raid failed’. In what was good psychology but bad staff work, the commander of the 46th Minensuchflottille, Kapitänleutnant Armin Zimmerman,11 changed the order of the messages so that the first signal on the list read ‘raid successful’. However, he failed to record this change.

The men embarked on M4613, commanded by a very experienced and reliable chief petty officer, Obersteuermann Koenig, on 4 April – Westhoff’s birthday – and made a successful covert landing by inflatable assault boats on Cape de la Hague on 5 April, though one man fell overboard and lost his kit. Westhoff noted that the inflatable assault boats were left on the beach, with no attempt to conceal them. The raiders made their way through an old German minefield and, marching by night and laying up by day, made their way towards Cherbourg. Passing an American billet, they could hear US soldiers singing and laughing. Westhoff recalls they were ‘apparently celebrating; to them the war seemed far away’. Hiding in undergrowth, they watched ‘an enormous and endless stream of U.S. Supply trucks passing by’.

Westhoff set up his radio and transmitted a brief signal confirming that the party had landed safely – it was acknowledged promptly by the Naval HQ in Guernsey. It was at this juncture that the engineers realised that their demolition stores were insufficient for the task of destroying the railway bridge, so Lt Maltzahn instead decided to attack tracks and rolling stock at Cherbourg. During the night the men marched openly along roads, with the officer answering in French when challenged in English and vice versa. The bluff worked.

Close to their target, Westhoff and his mate, who had carried the radio batteries, lay up at an agreed RV. They heard gunfire and, after an interval, only Maltzahn returned – they waited and, realising that the raid had failed, started to make their way back to the coast. They transmitted the first coded message on the pad and at the Naval HQ on the Channel Islands there was delight that the railway link had been cut. It was at this point that Zimmerman remembered that he had changed the order, and the cluster of numbers and letters actually meant ‘raid failed’; he was able to alert Vizeadmiral Hüffmeier before he transmitted a triumphant signal to Berlin. The Americans were now on full alert, searching for the raiders. Westhoff had received instructions from the HQ on Guernsey that he was to destroy his radio set and codebooks.

Maltzahn left the two radio operators hiding in a barn but failed to tell them where they could be picked up by minesweeper M4613, and when four Jeeps mounting Browning .50 machine guns surrounded the barn, the sailors knew they would have to surrender. Ironically, as they climbed down the ladder, the first GI to enter the barn was so nervous when he saw them that he put his hands up.

The US Army intelligence officers who interrogated Westhoff and his fellow radio operator used coercive techniques, including pointing a Colt 45 in their faces and the offer and then instant denial of food. Westhoff was taken to the naval prison at Cherbourg, where he caught ’flu, and was then moved to a ward in the naval hospital, where there were twenty seriously ill men but no medical support. The questioning continued, with the Americans insisting that he repair his radio so that negotiations could begin with Guernsey to arrange a surrender. Westhoff explained that he was a radio operator and not a technician.

He was then sent to a POW camp for ‘trouble-makers’ that was run by the French. It was a short but unpleasant stay that ended when he was transferred to the UK, and then on 23 February 1946 he was released and repatriated to Münster.

It was while he was in the UK, at Featherstone Park POW camp, that he learned what had happened to Maltzahn. The young officer made his way to the RV, a point 15km west of Cherbourg and just within the 18km range of the guns on Alderney. The minesweeper was waiting offshore. An inflatable assault boat was sent to collect him, and Maltzahn, who Koenig noted was ‘dirty and hungry’, bleeding from several wounds and limping, was helped on board. The officer was still carrying his MP40 sub-machine gun. The skipper of the minesweeper was not happy that Maltzahn had abandoned the signallers and, worse still, not told them the location of the RV.

Back on the Channel Islands, Westhoff was awarded the Iron Cross First and Second Class, but when Koenig raised the situation of Westhoff with Hüffmeier, the admiral ordered that Westhoff be promoted to Funkmaat. After the war, Koenig made strenuous efforts to track down Westhoff and they met in 1948.

Elated by the success of the Granville raid, Vizeadmiral Hüffmeier was already planning another attack on the port – reasoning that the Americans would not expect a repeat attack. A group of volunteers would take the SS Eskwood, loaded with concrete blocks, and sink her at the entrance to the harbour, while another team would block the harbour at St Malo using a freighter that had been laid up in the Channel Islands. The blockship crews would then be evacuated by high-speed launches. The date set for the great attack was to be 7 May, but Admiral Karl Dönitz, whom Hitler had named in his will as the new national leader, ordered Vizeadmiral Hüffmeier not to launch any offensive operations. In fact, it was on 7 May that the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany was signed in Rheims – the attack on Granville would be the last major raid.

The Channel Islanders’ leaders, in these last months, dreaded the possibility that Hüffmeier might attempt to hold out after a German capitulation. To capture and liberate the islands would have involved an Allied bombardment and the destruction of everything, and of everyone whom they had worked so hard to save. Fortunately, they became aware that they had allies amongst the Germans themselves. There was resentment by soldiers at having a naval officer as commander-in-chief, fear and dislike of Nazism by men like Baron von Aufsess and Baron von Helldorf, who had never been Nazi Party men, and finally troops who had been stationed for years on the islands felt more in common with the civilian populations than with ‘outsiders’ like Hüffmeier.

A month before the war ended, Vizeadmiral Hüffmeier had addressed a mass meeting in the Forum Cinema, St Helier, Jersey, where he explained the importance of defending the Channel Islands. It was stirring stuff – an attack by the British and Americans might happen at any moment and put them in the front line. They must prepare for this hour spiritually and materially; the more desperate the times, the more united they must be. It was reported by the rather incongruously named Deutsche-Guernsey Zeitung on 19 March 1945:

Vice-Admiral Hüffmeier left no doubt in the minds of his audience that, with firm, unshakable faith in the victory of our just cause, he is determined to hold as a pledge, to the very end, the Channel Islands which have been entrusted to him by the Führer. A settlement of accounts with the Anglo-Americans, arms in hand, is quite possible, and perhaps not far ahead … Those who kept within their hearts the ideal of National Socialism, in its original purity, would have the upper hand.

On Hitler’s birthday, troops were assembled in the Regal Cinema in St Peter Port, Guernsey, to hear a similar message, and the admiral even took it to the garrison of Sark. For the men on the tiny island, he had ‘inspiring’ words – if they did not resist an Allied attack they would be sent to the Eastern Front, a front that was now inside the borders of the Third Reich.

Key installations on the islands were rigged with demolition charges, among them the new jetty at St Peter Port, where some 207 big 27cm shells were removed from the concrete piles following the liberation.

On 3 May, news of Hitler’s death reached the Channel Islands. The German-controlled Jersey Evening Post ran the headline ‘Adolf Hitler Falls at His Post’, and on public buildings on the islands swastika flags flew at half mast. It was three days after Hitler had shot himself in the bunker in Berlin, and though the paper said that he ‘met a hero’s death’ fighting ‘the Bolshevik storm flood’, even then it was widely suspected that he had committed suicide.

On 8 May, as Churchill formally announced the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany, a similar demand was put to Hüffmeier. His representative, a nervous young naval officer, Armin Zimmerman, kept the rendezvous with the destroyers HMS Bulldog and HMS Beagle. His journey to and from the warships was slightly humiliating, from a minesweeper trawler in a three-man inflatable dingy rowed by Kriegsmarine ratings. On board, he took a deep breath and told the British he had been authorised to discuss an armistice, not a surrender. His hosts replied that it was surrender or nothing. Zimmerman took another deep breath and said his instructions were that the British must withdraw or they would be fired on.

The two ships withdrew out of range. That night, saner voices pressured Vizeadmiral Hüffmeier to change his mind. The ships returned; Hüffmeier threatened to open fire when they arrived ahead of the designated time. Since Hüffmeier could not bring himself to attend the surrender negotiations, Generalmajor Heine, Hüffmeier’s deputy, signed the surrender document. Ironically, the vessel that transported Heine to HMS Bulldog was M4613 Kanalblitz, the minesweeper that had landed the Maltzahn sabotage patrol on mainland France.

The final act was left for von Aufsess to announce, at a hastily convened meeting of Channel Island elders: ‘Der Krieg ist zu Ende, und in den Kanalinseln auch’ (‘The war is over, and in the Channel Islands too’).

Only a small number of people within the Admiralty knew that HMS Bulldog had already won herself a place in history – but one that would remain secret until the early 1970s. On 9 May 1941, she was responsible for the capture of U110, Sub Lt David Balme finding the Enigma code machine ciphers and, critically, the current codebooks. U110 was taken in tow and Bulldog kept her afloat for seventeen hours, then let the towline slip. The intention was to tow U110 into Iceland, but the Admiralty realised this would have been a massive error of judgement. In the event, allegedly, U110 resolved the matter herself by sinking.

At 3 p.m. on 8 May, Churchill announced to the world, ‘Our dear Channel islands will be freed today.’

The Beagle returned on 12 May, and the British took Hüffmeier into formal custody. His last order was that when they came ashore his men should greet the British with Nazi salutes. Most ignored him, since by now they were too drunk to bother.

Hundreds of illicit wireless sets were brought into the open for the people of Jersey, Guernsey and Sark to learn from Churchill that nearly five years of occupation were almost over. A German soldier climbed to the top of a crane in Jersey harbour to fly the Union flag. British soldiers were mobbed, and on Guernsey, a British colonel’s bald head was coated in ersatz lipstick. Aboard HMS Bulldog, after endorsing the surrender document, Coutanche smoked real tobacco for the first time in years and washed his hands in real soap (see Appendix VI).

The Nestegg had finally hatched.

The work of quiet heroes could now be made public. On Jersey, the heroism of physiotherapist Albert Bedane could be acknowledged. It was to his house that Erica Richardson, a Dutch Jew, fled after she had given her German guard the slip in June 1943. The Germans combed St Helier for her, and Bedane risked execution by hiding her until the island was liberated. He also sheltered an escaped French prisoner of war and Russian slave labourers, on the principle, in his words, that he ‘might as well be hanged for a sheep as for a lamb’.12

Besides the award of the OBE by the British government for his courageous conduct, Wilfred ‘Billy’ Bertram, a former corporal in the Canadian Army, was also awarded the United States Medal of Freedom by the US government after the war for the help he gave the USAAF air crew in their escape. In Outpost of Occupation, Turner observes that the award of an OBE to Bertram was ‘the only nod in the direction of the resistance’ by the British government, which was embarrassed by what had unjustly been perceived as the comparative passivity of the population during the occupation.

Another person who was not island-born but gave valuable support to escapers, was Irishman Dr Noel McKinstry. He was one of the few islanders who was prepared to help Soviet slave workers, and had the resources and contacts to provide them with identity and ration cards. He was one of a network of islanders who provided safe houses and encouraged them to adopt English names, such as Bill, George or Tom, and to learn English in order to avoid detection. With papers and a command of English, they were able to find work and so become self-sufficient. McKinstry was awarded an OBE in the occupation honours.

Remarkably, on Jersey, the mother and aunt of the youthful Stella Perkins, Augusta Metcalfe and Claudia Dimitrieva, were both Russians who had come to the island as refugees following the Bolshevik revolution in 1919. Islanders knew that they were Russian, so escaped Russian slave labourers would be referred to them as a safe house. Escaped Russians would sometimes simply call in to have a chance to talk in Russian about their homeland in a domestic setting. As Stella recalled, these meetings – with enemy soldiers marching past on the street below – were ‘one in the eye of the Germans’.

One Russian, Georgio Kozloff, was a gymnast and when Stella made him some swimming trunks out of an old pullover, he went down to the open air swimming pool at St Helier and did some spectacular dives. Stella was with him and she was terrified that he might be spotted by men of the Feldpolizei, whose HQ at Silvertide guest house overlooked the pool.

Some, however, would only be honoured in the memory of the islanders. Louisa Gould hid Fyodr Polycarpovitch Burriy, an escaped Russian slave labourer whom she took in because she had lost a son in the war and was determined to do an act of kindness ‘for another mother’s son’. Named ‘Bill’, Burriy lived with her for two and a half years before Louisa was betrayed by a neighbour. While the Russian escaped, she was arrested and, on 22 June 1944, sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for ‘failing to surrender a wireless receiving apparatus, prohibited reception of wireless stations and abetting breach of the working peace and unauthorised removal’. The unauthorised removal was sheltering ‘Bill’. She was found guilty and sent to a concentration camp along with her brother, Harold Le Druillenec.

Louisa was gassed in Ravensbrück concentration camp and Harold would be the only British survivor of the notorious Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, a place that he recalled as ‘the foulest and vilest spot that ever soiled the surface of this Earth’.13

The German soldiers on Alderney surrendered a week after the main Channel Islands. Their commander, Oberst Schwalm, ordered that the camps that had housed the forced labourers be burned to the ground, and destroyed all records connected with their use before the island was liberated on 16 May.

On Thursday 10 May, a party of British soldiers crossed from Guernsey to Sark. The small detachment marched up from the harbour surrounded by excited islanders, and then along the Avenue, throwing sweets and cigarettes to the delighted crowds, and accepted the surrender of the Kriegsmarine lieutenant left commanding the little garrison. However, for the next week, the governor, Seigneur Dame Sybil Hathaway, was left in command of the German troops.

To the west of Alderney, on the Casquets, on 17 May two officers and twenty men were taken off the lighthouse, but Trinity House left six prisoners on the rock to continue the maintenance of the lighthouse until they could be replaced by British lighthouse keepers.

The very last Wehrmacht soldiers to surrender on the Channel Islands were the small detachment manning the observation post on the tiny island cluster of the Minquiers. A French fishing boat, skippered by Lucian Marie, approached the islands and anchored offshore. A fully armed German soldier came down to the jetty from the fishermen’s cottages on Le Maître, the largest island, and shouted across to the Frenchman, ‘We’ve been forgotten by the British, perhaps no one on Jersey told them we were here, I want you to take us over to England, we want to surrender.’

It was 23 May 1945.

Notes

1 It consisted of eight Heer assault detachments (mainly the 319. Infanterie-Division) consisting of nine officers and 148 men; two Kriegsmarine naval detachments of one officer and twenty men; as well as the following naval vessels:

S112, a fast motor torpedo boat or Schnelleboot. This craft, commanded by Leutnant zur See der Reserve Nikelowski, had escaped from Brest. Nikelowski, in peacetime a whaler captain, was a skilled seaman.

Four M40-class minesweepers of the 24th Minesuchflottile, M412, M432, M442 and M452. Commanded by Kapitanleutnant Mohr, these ships were armed with one 10.5cm SK c/32 ship’s gun and numerous 3.7cm and 2cm flak guns.

Two auxiliary minesweepers of the 46th Minesuchflottille and 2nd Vorpostenflottile, commanded respectively by Kapitanleutnant Zimmermann and Fregattenkäpitan Lensch.

Gruppe Karl, three ‘artillery carriers’ or Artillerie-Träger, AF65, AF68 and AF71, survivors of the 6th Artillerieträgerflotille. Originally based at Cherbourg, the vessels were commanded by Oberleutnant zur See Otto Karl.

V228, V229 War Fishing Cutters (Kriegsfischerkutter, KFK) of the 2ndVorpostenflottille.

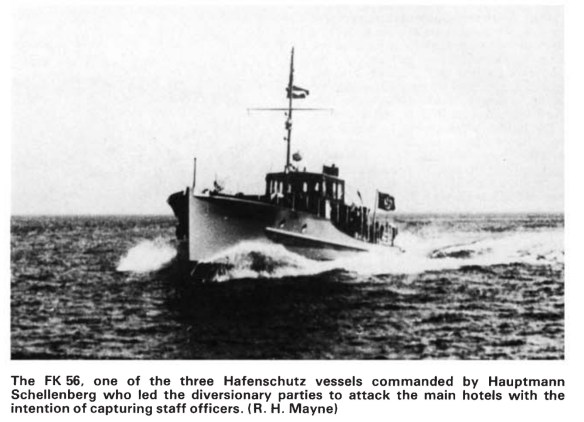

FK01, FK04, FK56 Harbour Protection Vessels (Hafenschutzboot) of the Hafenschutzflottille Kanalinseln.

FK60, a captured Allied LCV(P). The prefix FK stands for Frankreich Kanalinseln, or French Channel Islands. The ships were commanded by Kapitänleutnant der Reserve Lamperdorff.

2 Carl-Friedrich Mohr (10 May 1907 – 29 January 1984) was a career naval officer who had commanded 24th Minensuchflottille Karl Friedrich Brill.

3 The Artilleriefährprahm or AFP (artillery ferry) was a gunboat derivative of the Marinefährprahm (MFP), the largest type of landing craft used by the Kriegsmarine during the Second World War. These ships were used for escorting convoys, shore bombardment and mine laying. They were fitted with two 8.8cm guns and 2cm AA guns. The AFP were mainly built in Belgian yards and converted in Holland.

4 The six men of the Luftwaffe may have been the crew of a 2cm flak 30 or 38 anti-aircraft gun. The weapon weighed 450kg (992lb) and could therefore have been manhandled into position on the dock. In a direct fire role, the 20mm shells fired at close range would have been devastating against soft targets.

5 The M412 minesweeper (Minensuchboot) was built in the 1940s by N.V. Koninklijke Mij ‘De Schelde’ shipyard located in Vlissingen, the Netherlands, as a minesweeper or escort vessel for the Kriegsmarine. It had a transverse frame of steel construction, which was partly welded, and also had eleven watertight compartments and a double bottom with hard-chine foreship and tug stern. The superstructure, bridge etc. was armoured up to 10mm in thickness. The propulsion system installed in these vessels was two vertical three-cylinder triple expansion engines. When used as minesweepers, the Kabel Fern Raum Gerat (KFRG) system was employed, which used generators producing 60V, 20kW to power the magnetic sweeping gear.

6 John Alexander, who would be the only UNRRA official to be captured during the war, was very much a man of peace. He had been warden at Oxford House educational settlement, Risca, Monmouthshire. Oxford House had been established during the 1920s, when the Lord Mayor of London made an appeal to help people impoverished by industrial strife. In response, the Mayor of Oxford’s Mining Distress Committee was formed to organise and dispatch aid to coalmining areas, including Risca. Some public utility works at Risca were subsidised and relief in other forms was contributed. Alexander took over as warden from the pioneering Mr and Mrs David Wills, who had been joint wardens. After the war, Alexander became warden of the Mary Ward Centre, the adult education establishment in Bloomsbury, and he held this post until his retirement in 1971. He died on 2 December 1981.

7 Lightoller was the oldest son of Charles Herbert Lightoller, the second officer on the RMS Titanic who was the most senior surviving member of the crew to survive the disastrous sinking in 1912. In the First World War, he would serve with distinction in the Royal Navy, winning a bar to his DSC. In the Second World War, as a civilian, along with his son, Frederic, he took a ‘little ship’ to Dunkirk in 1940 to assist with the evacuation of the BEF. His youngest son, Brian, a bomber pilot in the RAF, had been killed on the first day of the war in a daylight raid on Germany. Frederic is buried at the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Bayeux, Normandy.

8 A variety of armaments were fitted to merchant vessels, typically a 4in deck gun at the stern, sometimes a 12pdr (3in shell), usually at the bow, mounted as either LA (low angle) for use against surfaced U-boats or surface raiders, or HA (high angle) for anti-aircraft use. Initially, the light machine guns were manned by 500 men of the Royal Artillery, Light Machine Gun sections, who were taken on and off vessels as they arrived and departed from British ports. The effectiveness of these army gunners was quickly realised, and the Maritime Anti-Aircraft Regiment Royal Artillery was formed in 1941, renamed the Maritime Royal Artillery (MRA) in January 1943.

9 The Channel Island Occupation Society was formed in 1961. However, it can trace its roots back to 1956, when two Guernsey schoolboys, Richard Heaume and John Robinson, formed a club to collect occupation relics. In defiance of their elders, including their headmaster, they explored bunkers and tunnels on the island, recovering helmets, gas masks and other items of equipment. By 1961, Richard Heaume’s collection had outgrown the attic of the family home and the club, named The Society for the Preservation of German Occupation Relics, was no longer confined to the pupils of Elizabeth College. The name was shortened to The German Occupation Society in 1963 and, seven years later, the word ‘German’ was dropped. Today there are two branches, one in Jersey and the other in Guernsey.

10 Mohr, who prior to the Granville raid had commanded 24th Minensuchflottille ‘Karl Friedrich Brill’, would survive the war and die at the aged of 76 on 29 January 1984 at Bodenbach.

11 In 1972, Zimmerman would become the first naval officer to hold the rank of Inspector-General of the West German Armed Forces, the Bundeswehr, serving in this post until 1976.

12 Albert Bedane (1893–1980) was born in Angers, France, and lived in Jersey from 1894. He served in the British Army from 1917 to 1920, and was naturalised as a British subject by the Royal Court of Jersey in 1921. On 4 January 2000, Albert Bedane was recognised as ‘Righteous Among the Nations’, also known as ‘Righteous Gentile’, by the State of Israel. In 2010, Bedane was posthumously named a ‘British Hero of the Holocaust’ by the British government. A plaque marks the house where he sheltered the escapees.

13 In May 1965, the Soviet Union recognised the courage of the Channel Islanders who had sheltered Soviet slave labourers and awarded them twenty gold Poljot brand (the Russian word for ‘flight’) watches, made by the First Moscow Watch Factory. Recipients were Albert Bedane, Claudia Dimitrieva, François Flamon, Ivy Forster, René Franoux, Royston Garret, Louisa Gould and Dr McKinstry (posthumously), Leslie Huelin, John Le Breton, Norman Le Brocq, Mike Le Cornu, Harold Le Druillenec, René Le Mottée, Francois Le Sueur, Bob Le Sueur, Augusta Metcalfe, Oswald Pallot, Leonrad Perkins and William Sarre.